Black Fungi are one of the main group of microorganisms responsible for the biodeterioration of stone cultural heritage artifacts. The term “bColack fungi” refers to a very huge group of dematiaceous fungi, unrelated phylogenetically, which have in common the presence of melanin in the cell wall that confers an olive brown appearance to the colony. Another common characteristic is the ability to withstand hostile environments such as scarcity of nutrients, high solar irradiation, scarcity of water, high osmolarity, and low pHonization pattern, taxonomy, and methods to eradicate their settlement are discussed here.

- stone cultural heritage

- black fungi

- MCF

- biodeterioration

- control

1. Background

2. Black Fungi and Stone Monuments: An Intimate Connection

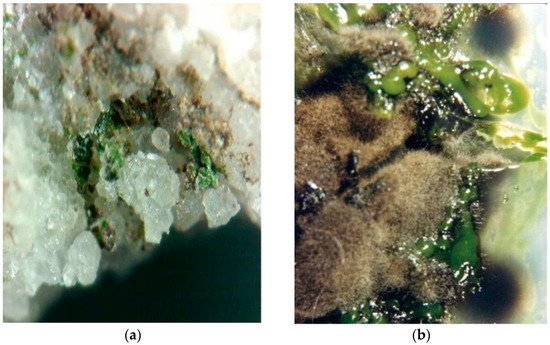

Beginning in the 1990s, black fungi were described as one of the most likely groups of microorganisms responsible for the biodeterioration of the stone monuments [21][22][23][24] and it was confirmed in the following decades [6][18][25][26]. The term “black fungi” refers to a very huge group of dematiaceous fungi, unrelated phylogenetically, which have in common the presence of melanin in the cell wall that confers an olive brown appearance to the colony [27]. Another common characteristic is the ability to withstand hostile environments such as scarcity of nutrients, high solar irradiation, scarcity of water, high osmolarity, and low pH [15][19][28]. As reported by Gueidan et al. [29] the ancestors of black fungi were well adapted to live in oligotrophic environments such as rock surfaces or sub-surfaces, and currently they can also grow in anthropogenic habitats such as glass, silicon, organic surfaces, metals [30], or consolidants applied on the stone [9]. Their resilience is related to the extremotolerant or even polyextremotolerant characteristics of the species. The stress-tolerance is due to different factors such as: pigmentation, and in particular melanins production; mycosporine-like substances; morphological and metabolic versatility; meristematic development; and oligotrophy [31][32][33]. All these characteristics make them very suitable for colonizing outdoor rocks and built stones due to the fact that those surfaces can be exposed to extreme environments [17][18][19]. This group of fungi includes (a) fast growing hyphomycetes of epiphytic origin, recognizable under microscope by the presence of typical conidiophores and spores; (b) pleomorphic hyphomycetes that include the “black yeasts”, showing a yeast-like form, and the so-called “black meristematic fungi” with a Torula-like growth pattern (Figure 1).

| Class/Order | Genera * | Substrate | Environmental and Climatic Features | Alterations Associated to Fungal Colonization | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dothideomycetes incertae sedis | Coniosporium | Calcarenite, granite, limestone, marble | Mediterranean climate, urban environment | Grayish-black patina, pitting, black spots, greenish to dark green patina, crater shaped lesions, chipping, exfoliation, sugaring, crumbling, superficial deposit, and biofilm | [36][38][43][44][45][46][47][48][49] | ||

| Dothideomycetes/Capnodiales incertae sedis | Capnobotryella | Limestone, marble | Mediterranean climate, continental climate, and urban environment |

Black spots, crater shaped lesions, chipping, exfoliation, sugaring, crumbling, pitting, superficial deposit, and biofilm formation | [45][48][50][51][52] | ||

| Constantinomyces | Sandstone | Urban environment, temperate climate | Discolorations, patina | [53] | |||

| Pseudotaeniolina | Marble, sandstone | Mediterranean climate, arid and desert climate | Biological green patina | [54][55][56] | |||

| Dothideomycetes/Capnodiales | Aeminium | Limestone | Temperate climate | Black discoloration with salt efflorescence | [57] | ||

| Dothideomycetes/Cladosporiales | Cladosporium | Calcarenite, granite, limestone, marble, plaster, sandstone, tufa | Ubiquitous worldwide distribution in indoor environments and outdoor | Dark alterations, black spots, black patinas, detachment of marble grains, light grayish patina, crater shaped lesions, chipping, exfoliation, sugaring, crumbling, pitting, superficial deposit, biofilm, black crusts, green biofilm with salt efflorescence, stone erosion and disintegration, and discoloration | [26][39][46][48][49][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67] | ||

| Verrucocladosporium | Limestone, marble, sandstone | Mediterranean climate, temperate climate, and urban environment | Black patina, discoloration | [36][53] | |||

| Dothideomycetes/Dothideales | Aureobasidium | Granite, limestone, marble, plaster, sandstone |

Urban environment, Mediterranean climate, temperate climate, indoor environment, and urban environment | Black patina, black spots, detachments, superficial deposit, biofilm, discolorations with or without salt efflorescence, black crusts, and stone erosion and disintegration | [36][39][45][49][53][63][64][65][68] | ||

| Dothideomycetes/Mycosphaerellales | Salinomyces | Marble, sandstone | Mediterranean climate | Black patina | [36] | ||

| Neocatenulostroma | Limestone, sandstone | Temperate climate, urban environment | Discolorations and/or patina, structural damage | [53] | |||

| Neodevresia | Limestone, marble, plaster, tufa | Mediterranean climate | Black patina, discolorations, structural damage | [36][53][55][63] | |||

| Saxophila | Marble | Mediterranean climate | Black patina | [36] | |||

| Vermiconidia | Limestone, marble, travertine | Mediterranean climate, urban environment | Black patina | Neodevriesia sardiniae[36] | |||

| CCFEE 6202 | KP791765 | Dothideomycetes/Neophaeothecales | Neophaeotheca | Marble | Mediterranean climate | Black patina | [ |

| Neodevriesia sardiniae | CCFEE 6210 | 36 | ] | ||||

| KP791766 | Dothideomycetes/Pleosporales | Alternaria | Calcarenite, granite, limestone, marble, plaster, tufa | Ubiquitous worldwide distribution in indoor environments and outdoor | Black spots, black patina, detachment of marble grains, greenish to dark green patina, biofilm, black crusts, green-black patina; and blackish patina | [39] | |

| Saxophila tyrrhenica | [ | 46 | ] | [ | 49 | CCFEE 5935][58][59][60][63][64][66][67] | |

| KP791764 | Epicoccum | Granite, limestone, marble | Urban environment, mediterranean climate, and temperate climate | Black spots, black patinas, detachment, superficial deposit, biofilm, blackish patina, green biofilm, and dark and green biofilm with salt efflorescence | [39][45][49][60][64] | ||

| Aeminium ludgeri | E12 | MG938054 | Phoma | Calcarenite, granite, limestone, marble, plaster, tufa | Mediterranean climate, temperate climate, urban environment, continental-cold climate, and indoor and outdoor environments | Black spots, black patinas, detachment of marble grains; color changes, crater shaped lesions, chipping and exfoliation, sugaring, crumbling, pitting, superficial deposit, biofilm, and black crusts | [39][46][48][49][58][63] |

| Aeminium ludgeri | E16 | MG938061 | Dothideomycetes/Venturiales | Ochroconis | Calcarenite | Subterranean environment | Black patina |

| Neocatenulostroma sp. | CR1 | [ | 69 | ] | |||

| KY111907 | Eurotiomycetes incertae sedis | ||||||

| Constantinomyces | Sarcinomyces | Marble | Mediterranean climate | Black spots | [70] | ||

| Eurotiomycetes/Chaetothyriales | Cyphellophora sp. | Plaster | Mediterranean climate | Black/grayish patina | [63] | ||

| Exophiala | Calcarenite, limestone, marble, sandstone |

Mediterranean climate, urban environment, temperate climate, and hypogean environment | Dark alterations, black spots, black patinas, detachment of marble grains, discolorations, and visible structural damage | [26][36][39][45][53][71] | |||

| Lithophila | Limestone, marble | Mediterranean climate, urban environment, and dry continental climate |

Black spots, black patinas, detachment of marble grains | [36][39][72] | |||

| Knufia | Limestone, marble, sandstone travertine |

Mediterranean climate, urban environment, continental temperate climate, and dry continental climate | Black and grey spots, dark macropitting, biopitting, crater shaped lesions, chipping, exfoliation, sugaring, crumbling, discolorations, patina, and visible structural damage | [36][40][43][45][48][53][72][73][74] | |||

| Rhinocladiella | Marble | Mediterranean climate | Black spots, crater shaped lesions, chipping and exfoliation, sugaring, crumbling, and pitting | [48] | |||

| Eurotiomycetes/Mycocaliciales | Mycocalicium | Marble | Mediterranean climate, urban environment | Black spots, crater shaped lesions, chipping and exfoliation, sugaring, crumbling, and pitting | [45][48] |

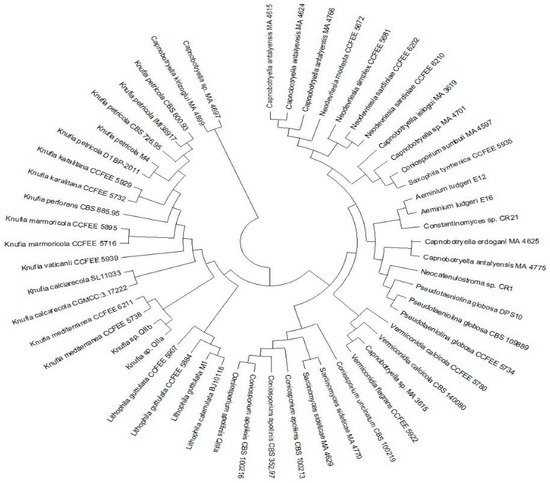

| Taxon | Strain | ITS rDNA |

|---|---|---|

| Capnobotryella antalyensis | MA 4615 | AJ972858 |

| Capnobotryella antalyensis | MA 4624 | AJ972850 |

| Capnobotryella antalyensis | MA 4766 | AJ972851 |

| Capnobotryella antalyensis | MA 4775 | AJ972860 |

| Capnobotryella isilogui | MA 3619 | AM746201 |

| Capnobotryella erdogani | MA 4625 | AJ972857 |

| Capnobotryella kirizoglui | MA 4899 | AJ972859 |

| Capnobotryella sp. | MA 4701 | AJ972856 |

| Capnobotryella sp. | MA 4697 | AJ972855 |

| Capnobotryella sp. | MA 3615 | AM746203 |

| Neodevriesia modesta | CCFEE 5672 | KF309984 |

| Neodevriesia simplex | CCFEE 5681 | KF309985 |

| sp. | ||

| CR21 | ||

| KY111911 | ||

| Pseudaeniolina globosa | DPS10 | MH396690 |

| Pseudotaeniolina globosa | CBS109889 | NR136960 |

| Pseudotaeniolina globosa | CCFEE5734 | KF309976 |

| Vermiconidia calcicola | CBS 140080 | NR_145012 |

| Vermiconidia calcicola | CCFEE 5780 | KP791761 |

| Vermiconidia flagrans | CCFEE 5922 | KP791753 |

| Coniosporium uncinatum | CBS 100219 | AJ244270 |

| Coniosporium apollinis | CBS 100213 | AJ244271 |

| Coniosporium apollinis | CBS 352.97 | NR159787 |

| Coniosporium apollinis | CBS 100216 | AJ244272 |

| Coniosporium apollinis | QIIIa | MH023395 |

| Lithophila catenulata | BJ10118 | JN650519 |

| Lithophila guttulata | M1 | MW361305 |

| Lithophila guttulata | CCFEE 5884 | KP791768 |

| Lithophila guttulata | CCFEE 5907 | KP791773 |

| Knufia mediterranea | CCFEE 5738 | KP791791 |

| Knufia mediterranea | CCFEE 6211 | KP791793 |

| Knufia vaticanii | CCFEE 5939 | KP791780 |

| Knufia calcarecola | SL11033 | JQ354925 |

| Knufia calcarecola | CGMCC 3.17222 | KP174862 |

| Knufia marmoricola | CCFEE 5895 | KP791775 |

| Knufia marmoricola | CCFEE 5716 | KP791786 |

| Knufia perforans | CBS 885.95 | AJ244230 |

| Knufia karalitana | CCFEE 5732 | KP791782 |

| Knufia karalitana | CCFEE 5929 | KP791783 |

| Knufia petricola | CCFEE 726.95 | KC978746 |

| Knufia petricola | CBS 600.93 | KC978744 |

| Knufia petricola | IMI38917 | AJ507323 |

| Knufia petricola | D1 | JF749183 |

| Knufia petricola | M4 | FJ556910 |

| Knufia sp. | QIIa | MH023393 |

| Knufia sp. | QIIb | MH023394 |

3. How to Control Black Fungi

Very little is said regarding the effectiveness of treatments against black fungi. Black fungi, especially meristematic ones, are very difficult to eradicate and tend to be one of the first colonizers after cleaning procedures. In order to achieve protection of an artifact, both indirect and direct methods should be implemented. Direct treatments aiming to kill/reduce black fungi on the stone should be different on the basis of their colonization pattern (diffuse patina, spot-like colonization, or intercrystalline growth) and on the characteristics of the environment. Among the potential methods commonly used to control biodeterioration, physical methods such as mechanical removal and UV and heat shock treatments[81][82], are not very effective against black fungi[83][84]. Regarding chemical methods, in laboratory conditions, classical biocides (e.g., Preventol RI 50, Biotin R, RocimaTM 103) are still the most effective [83][85] and in the field they produce efficient results during cleaning procedures. Plant based extracts show a scarce effectiveness against fungi, and this difficult group of microorganisms is not even taken into account to assess their activity[86]. Nanoparticles are commonly used as biocides due to their activity against algae, cyanobacteria, and most bacteria, but they are not really satisfactory against black fungi. Protective coatings with antifouling properties may have various effects. In fact, TiO2 based coatings, pure or doped with Ag, show a good effect but are limited to a short/medium term after application [86]. However, in both laboratory and field conditions, after treatments with titania-based coatings, black fungi are the first to recolonize the stone surface in dry environments, while algae first appears in damping walls[63]. Very recently, in laboratory conditions, cholinium@Il based coatings have shown that the use of Il’s with a 12 C chains and DBS as anion in combination with nanosilica coatings (e.g., Nano Estel) could be effective against the colonization of black fungi for a period of time over 30 months [87]. One possible explanation of this scarce effectiveness of most treatments against black fungi is that they possess a genetic resistance to environmental stresses, as reported the previous paragraphs. Therefore, the different mechanisms concurring to the stress protection response may interfere to the biocidal treatments. Understanding the cause of their resilience could improve the strategies for their control.

References

- Krumbein, W.E. Microbial interactions with mineral materials. In Biodeterioration 7, 1st ed.; Hougthon, D.R., Smith, R.N., Eggins, H.O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 78–100.

- Saiz-Jimenez, C. Biogeochemistry of weathering processes in monuments. Geomicrobiol. J. 1999, 16, 27–37.

- Sterflinger, K. Fungi as geologic agents. Geomicrobiol. J. 2000, 17, 97–124.

- Gadd, G.M. Geomicrobiology of the built environment. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 16275.

- Urzì, C. Biodeterioramento dei manufatti artistici. In Microbiologia Ambientale ed Elementi di Ecologia Microbica; Barbieri, P., Bestetti, G., Galli, E., Zannoni, D., Eds.; Casa Editrice Ambrosiana: Milano, Italy, 2008; pp. 327–346. ISBN 978-88-08-18434-4.

- Pinna, D. Microbial growth and its effect on inorganic heritage material. In Microorganisms in the Deterioration and Preservation of Cultural Heritage, 1st ed.; Joseph, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–35.

- Gorbushina, A.A. Life on the rocks. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1613–1631.

- Villa, F.; Stewart, P.S.; Klapper, I.; Jacob, J.M.; Cappitelli, F. Subaerial biofilms on outdoor stone monuments: Changing the perspective toward an ecological framework. BioScience 2016, 66, 285–294.

- Pinna, D. Coping with Biological Growth on Stone Heritage Objects: Methods, Products, Applications, and Perspectives, 1st ed.; Apple Academic Press: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2017; ISBN 9781771885324.

- Guillitte, O. Bioreceptivity: A new concept for building ecology studies. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 167, 215–222.

- Saiz-Jimenez, C. Deposition of anthropogenic compounds on monuments and their effect on airborne microorganisms. Aerobiologia 1995, 11, 161–175.

- Urzì, C.; De Leo, F.; Salamone, P.; Criseo, G. Airborne fungal spores colonising marbles exposed in the terrace of Messina Museum, Sicily. Aerobiologia 2001, 17, 11–17.

- Polo, A.; Gulotta, D.; Santo, N.; Di Benedetto, C.; Fascio, U.; Toniolo, L.; Villa, F.; Cappitelli, F. Importance of subaerial biofilms and airborne microflora in the deterioration of stonework: A molecular study. Biofouling 2012, 28, 1093–1106.

- Liu, B.; Fu, R.; Wu, B.; Liu, X.; Xiang, M. Rock-inhabiting fungi: Terminology, diversity, evolution and adaptation mechanisms. Mycology 2022, 13, 1–31.

- Selbmann, L.; Egidi, E.; Isola, D.; Onofri, S.; Zucconi, Z.; de Hoog, G.S.; Chinaglia, S.; Testa, L.; Tosi, S.; Balestrazzi, A.; et al. Biodiversity, evolution and adaptation of fungi in extreme environments. Plant Biosyst. 2013, 147, 237–246.

- Salvadori, O.; Municchia, A.C. The role of fungi and lichens in the biodeterioration of stone monuments. Open Conf. Proc. J. 2016, 7, 39–54.

- Liu, X.; Koestler, R.J.; Warscheid, T.; Katayama, Y.; Gu, J.-D. Microbial deterioration and sustainable conservation of stone monuments and buildings. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 991–1004.

- Sterflinger, K. Fungi: Their role in deterioration of cultural heritage. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2010, 24, 47–55.

- Urzì, C.; De Leo, F.; de Hoog, S.; Sterflinger, K. Recent advances in the molecular biology and ecophysiology of meristematic stone-inhabiting fungi. In Of Microbes and Art: The Role of Microbial Communities in the Degradation and Protection of Cultural Heritage; Ciferri, O., Tiano, P., Mastromei, G., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 3–19.

- Onofri, S.; Zucconi, L.; Isola, D.; Selbmann, L. Rock-inhabiting fungi and their role in deterioration of stone monuments in the Mediterranean area. Plant Biosyst. 2014, 148, 384–391.

- Wollenzien, U.; de Hoog, G.S.; Krumbein, W.E.; Urzì, C. On the isolation of microcolonial fungi occurring on and in marble and other calcareous rocks. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 167, 287–294.

- Diakumaku, E.; Gorbushina, A.A.; Krumbein, W.E.; Panina, L.; Soukharjevski, S. Black fungi in marble and limestones–an aesthetical, chemical and physical problem for the conservation of monuments. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 167, 295–304.

- Urzì, C.; Wollenzien, U.; Criseo, G.; Krumbein, W.E. Biodiversity of the rock inhabiting microflora with special reference to black fungi and black yeasts. In Microbial Diversity and Ecosystem Function; Allsopp, D., Colwell, R.R., Hawksworth, D.L., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1995; pp. 289–302.

- Sterflinger, K.; Krumbein, W.E. Dematiaceous fungi as a major agent for biopitting on mediterranean marbles and limestones. Geomicrobiol. J. 1997, 14, 219–230.

- De Leo, F.; Urzì, C. Microfungi from deteriorated materials of cultural heritage. In Fungi from Different Substrates; Misra, J.K., Tewari, J.P., Deshmukh, S.K., Vágvölgyi, C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 144–158.

- Isola, D.; Zucconi, L.; Cecchini, A.; Caneva, G. Dark-pigmented biodeteriogenic fungi in etruscan hypogeal tombs: New data on their culture-dependent diversity, favouring conditions, and resistance to biocidal treatments. Fungal Biol. 2021, 125, 609–620.

- de Hoog, G.S.; Guarro, J.; Gené, S.A.; Al-Hatmi, A.M.S.; Figueras, M.J.; Vitale, R.G. Atlas of Clinical Fungi, 4th ed.; Westerdijk Institute/Universitat Rovira Virgili: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019.

- Palmer, F.E.; Emery, D.R.; Stemmler, J.; Staley, J.T. Survival and growth of microcolonial rock fungi as affected by temperature and humidity. New Phytol. 1987, 107, 155–162.

- Gueidan, C.; Ruibal, C.; de Hoog, S.; Schneider, H. Rock-inhabiting fungi originated during periods of dry climate in the late Devonian and middle Triassic. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 987–996.

- Gostinčar, C.; Grube, M.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Evolution of fungal pathogens in domestic environments? Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 1008–1018.

- Gorbushina, A.A.; Whitehead, K.; Dornieden, T.; Niesse, A.; Schulte, A.; Hedges, J.I. Black fungal colonies as units of survival: Hyphal mycosporines synthesized by rock-dwelling microcolonial fungi. Can. J. Bot. 2003, 81, 131–138.

- Gostinčar, C.; Muggia, L.; Grube, M. Polyextremotolerant black fungi: Oligotrophism, adaptive potential and a link to lichen symbioses. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 390.

- Zakharova, K.; Tesei, D.; Marzban, G.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Wyatt, T.; Sterflinger, K. Microcolonial fungi on rocks: A life in constant drought? Mycopathologia 2013, 175, 537–547.

- Marchetta, A.; van den Ende, G.B.; Al-Hatmi, A.M.S.; Hagen, F.; Zalar, P.; Sudhadham, M.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Urzì, C.; de Hoog, S.; De Leo, F. Global molecular diversity of the halotolerant fungus Hortaea werneckii. Life 2018, 8, 31.

- Sterflinger, K.; Piñar, G. Microbial deterioration of cultural heritage and works of art—tilting at windmills? Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2013, 97, 9637–9646.

- Isola, D.; Zucconi, L.; Onofri, S.; Caneva, G.; de Hoog, G.S.; Selbmann, L. Extremotolerant rock inhabiting black fungi from Italian monumental sites. Fungal Divers. 2016, 76, 75–96.

- Staley, J.T.; Palmer, F.; Adams, J.B. Microcolonial fungi: Common inhabitants on desert rocks? Science 1982, 215, 1093–1095.

- De Leo, F.; Antonelli, F.; Pietrini, A.M.; Ricci, S.; Urzì, C. Study of the euendolithic activity of black meristematic fungi isolated from a marble statue in the Quirinale Palace’s Gardens in Rome, Italy. Facies 2019, 65, 18.

- Santo, A.P.; Cuzman, O.A.; Petrocchi, D.; Pinna, D.; Salvatici, T.; Perito, B. Black on white: Microbial growth darkens the external marble of Florence cathedral. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6163.

- Marvasi, M.; Donnarumma, F.; Frandi, A.; Mastromei, G.; Sterflinger, K.; Tiano, P.; Perito, B. Black microcolonial fungi as deteriogens of two famous marble statues in Florence, Italy. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 68, 36–44.

- Crous, P.W.; Schumacher, R.K.; Akulov, A.; Thangavel, R.; Hernández-Restrepo, M.; Carnegie, A.J.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Wingfield, M.J.; Summerell, B.A.; Quaedvlieg, W.; et al. New and interesting fungi. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2019, 3, 57–134.

- Abdollahzadeh, J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Coetzee, M.P.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; Crous, P.W. Evolution of lifestyles in Capnodiales. Stud. Mycol. 2020, 95, 381–414.

- Sterflinger, K.; de Baere, R.; de Hoog, G.S.; de Wachter, R.; Krumbein, W.E.; Haase, G. Coniosporium perforans and C. apollinis, two new rock-inhabiting fungi isolated from marble in the Sanctuary of Delos (Cyclades, Greece). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek J. Microb. 1997, 72, 349–363.

- De Leo, F.; Urzì, C.; de Hoog, G.S. Two Coniosporium species from rock surfaces. Stud. Mycol. 1999, 43, 70–79.

- Sterflinger, K.; Prillinger, H. Molecular taxonomy and biodiversity of rock fungal communities in an urban environment (Vienna, Austria). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek J. Microb. 2001, 80, 275–286.

- Ricca, M.; Urzì, C.E.; Rovella, N.; Sardella, A.; Bonazza, A.; Ruffolo, S.A.; De Leo, F.; Randazzo, L.; Arcudi, A.; La Russa, M.F. Multidisciplinary approach to characterize archaeological materials and status of conservation of the roman Thermae of Reggio Calabria site (Calabria, south Italy). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5106.

- Sert, H.B.; Sterflinger, K. A new Coniosporium species from historical marble monuments. Mycol. Prog. 2010, 9, 353–359.

- Sert, H.B.; Sümbül, H.; Sterflinger, K. Microcolonial fungi from antique marbles in Perge/Side/Termessos (Antalya/Turkey). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek J. Microb. 2007, 91, 217–227.

- Sazanova, K.V.; Zelenskaya, M.S.; Vlasov, A.D.; Bobir, S.Y.; Yakkonen, K.L.; Vlasov, D.Y. Microorganisms in superficial deposits on the stone monuments in Saint Petersburg. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 316.

- Sert, H.B.; Sümbül, H.; Sterflinger, K. A new species of Capnobotryella from monument surfaces. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 1235–1241.

- Sert, H.B.; Sümbül, H.; Sterflinger, K. Two new species of Capnobotryella from historical monuments. Mycol. Prog. 2011, 10, 333–339.

- Sert, H.B.; Wuczkowski, M.; Sterflinger, K. Capnobotryella isiloglui, a new rock-inhabiting fungus from Austria. Turk. J. Bot. 2012, 3, 401–407.

- Owczarek-Kościelniak, M.; Krzewicka, B.; Piątek, J.; Kołodziejczyk, Ł.M.; Kapusta, P. Is there a link between the biological colonization of the gravestone and its deterioration? Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 148, 104879.

- De Leo, F.; Urzì, C.; de Hoog, G.S. A new meristematic fungus, Pseudotaeniolina globosa. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek J. Microb. 2003, 83, 351–360.

- Egidi, E.; de Hoog, G.S.; Isola, D.; Onofri, S.; Quaedvlieg, W.; de Vries, M.; Verkley, G.J.M.; Stielow, J.B.; Zucconi, L.; Selbmann, L. Phylogeny and taxonomy of meristematic rock-inhabiting black fungi in the Dothideomycetes based on multi-locus phylogenies. Fungal Diver. 2014, 65, 127–165.

- Rizk, S.M.; Magdy, M.; De Leo, F.; Werner, O.; Rashed, M.A.-S.; Ros, R.M.; Urzì, C. A new extremotolerant ecotype of the fungus Pseudotaeniolina globosa isolated from Djoser Pyramid, Memphis Necropolis, Egypt. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 104.

- Trovão, J.; Tiago, I.; Soares, F.; Paiva, D.S.; Mesquita, N.; Coelho, C.; Catarino, L.; Gil, F.; Portugal, A. Description of Aeminiaceae fam. nov., Aeminium gen. nov. and Aeminium ludgeri sp. nov. (Capnodiales), isolated from a biodeteriorated art-piece in the old cathedral of Coimbra, Portugal. MycoKeys 2019, 45, 57–73.

- Nuhoglu, Y.; Oguz, E.; Uslu, H.; Ozbek, A.; Ipekoglu, B.; Ocak, I.; Hasenekoglu, I. The accelerating effects of the microorganisms on biodeterioration of stone monuments under air pollution and continental-cold climatic conditions in Erzurum, Turkey. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 364, 272–283.

- Cappitelli, F.; Principi, P.; Pedrazzani, R.; Toniolo, L.; Sorlini, C. Bacterial and fungal deterioration of the Milan cathedral marble treated with protective synthetic resins. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 385, 172–181.

- Cappitelli, F.; Nosanchuk, J.; Casadevall, A.; Toniolo, L.; Brusetti, L.; Florio, S.; Principi, P.; Borin, S.; Sorlini, C. Synthetic consolidants attacked by melanin-producing fungi: Case study of the biodeterioration of Milan (Italy) cathedral marble treated with acrylics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 271–277.

- Suihko, M.L.; Alakomi, H.L.; Gorbushina, A.; Fortune, I.; Marquardt, J.; Saarela, M. Characterization of aerobic bacterial and fungal microbiota on surfaces of historic Scottish monuments. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 30, 494–508.

- Ortega-Morales, B.O.; Narváez-Zapata, J.; Reyes-Estebanez, M.; Quintana, P.; De la Rosa-García del, C.S.; Bullen, H.; Gómez-Cornelio, S.; Chan-Bacab, M.J. Bioweathering potential of cultivable fungi associated with semi-arid surface microhabitats of mayan buildings. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 201.

- Ruffolo, S.A.; De Leo, F.; Ricca, M.; Arcudi, A.; Silvestri, C.; Bruno, L.; Urzì, C.; La Russa, M.F. Medium-term in situ experiment by using organic biocides and titanium dioxide for the mitigation of microbial colonization on stone surfaces. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 123, 17–26.

- Trovão, J.; Portugal, A.; Soares, F.; Paiva, D.S.; Mesquita, N.; Coelho, C.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Catarino, L.; Gil, F.; Tiago, I. Fungal diversity and distribution across distinct biodeterioration phenomena in limestone walls of the old cathedral of Coimbra, UNESCO World Heritage Site. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 142, 91–102.

- Trovão, J.; Gil, F.; Catarino, L.; Soares, F.; Tiago, I.; Portugal, A. Analysis of fungal deterioration phenomena in the first Portuguese King tomb using a multi-analytical approach. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 149, 104933.

- Mang, S.M.; Scrano, L.; Camele, I. Preliminary studies on fungal contamination of two rupestrian churches from Matera (Southern Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6988.

- Urzì, C.; De Leo, F.; Bruno, L.; Albertano, P. Microbial diversity in paleolithic caves: A study case on the phototrophic biofilms of the Cave of Bats (Zuheros, Spain). Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 116–129.

- Urzì, C.; De Leo, F.; Lo Passo, C.; Criseo, G. Intra-specific diversity of Aureobasidium pullulans strains isolated from rocks and other habitats assessed by physiological methods and by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD). J. Microbiol. Meth. 1999, 36, 95–105.

- Martin-Sanchez, P.M.; Nováková, A.; Bastian, F.; Alabouvette, C.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Two new species of the genus Ochroconis, O. lascauxensis and O. anomala isolated from black stains in Lascaux Cave, France. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 574–589.

- Sert, H.B.; Sümbül, H.; Sterflinger, K. Sarcinomyces sideticae, a new black yeast from historical marble monuments in Side (Antalya, Turkey). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2007, 154, 373–380.

- Isola, D.; Selbmann, L.; de Hoog, G.S.; Fenice, M.; Onofri, S.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X.; Zucconi, L. Isolation and screening of black fungi as degraders of volatile aromatic hydrocarbons. Mycopathologia 2013, 175, 369–379.

- Sun, W.; Su, L.; Yang, S.; Sun, J.; Liu, B.; Fu, R.; Wu, B.; Liu, X.; Cai, L.; Guo, L.; et al. Unveiling the hidden diversity of rock-inhabiting fungi: Chaetothyriales from China. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 187.

- Wollenzien, U.; de Hoog, G.S.; Krumbein, W.E.; Uijthof, J.M.J. Sarcinomyces petricola, a new microcolonial fungus from marble in the Mediterranean basin. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek J. Microb. 1997, 71, 281–288.

- Bogomolova, E.V.; Minter, D.W. A new microcolonial rock-inhabiting fungus from marble in Chersonesos (Crimea, Ukraine). Mycotaxon 2003, 86, 195–204.

- Tsuneda, A.; Hambleton, S.; Currah, R.S. The anamorph genus Knufia and its phylogenetically allied species in Coniosporium, Sarcinomyces, and Phaeococcomyces. Can. J. Bot. 2011, 89, 523–536.

- Nai, C.; Wong, H.Y.; Pannenbecker, A.; Broughton, W.J.; Benoit, I.; de Vries, R.P.; Guedain, C.; Gorbushina, A.A. Nutritional physiology of a rock-inhabiting, model microcolonial fungus from an ancestral lineage of the Chaetothyriales (Ascomycetes). Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 56, 54–66.

- Quaedvlieg, W.; Binder, M.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Summerell, B.A.; Carnegie, A.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Crous, P.W. Introducing the consolidated species concept to resolve species in the Teratosphaeriaceae. Persoonia 2014, 33, 1–40.

- Hao, L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, M.; Sun, G.; Gleason, M.L. A new species of Scolecobasidium associated with the sooty blotch and flyspeck complex on banana from China. Mycol. Prog. 2013, 12, 489–495.

- Samerpitak, K.; Van der Linde, E.; Choi, H.J.; Gerrits van den Ende, A.H.G.; Machouart, M.; Gueidan, C.; de Hoog, G.S. Taxonomy of Ochroconis, genus including opportunistic pathogens on humans and animals. Fungal Diver. 2014, 65, 89–126.

- Samerpitak, K.; Duarte, A.P.M.; Attili-Angelis, D.; Pagnocca, F.C.; Heinrichs, G.; Rijs, A.J.M.M.; Alfjorden, A.; Gerrits van den Ende, A.H.G.; Menken, S.B.J.; de Hoog, G.S. A new species of the oligotrophic genus Ochroconis (Sympoventuriaceae). Mycol. Progress 2015, 14, 6.

- Francesca Cappitelli; Cristina Cattò; Federica Villa; The Control of Cultural Heritage Microbial Deterioration. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1542, 10.3390/microorganisms8101542.

- Francesca Cappitelli; Cristina Cattò; Federica Villa; The Control of Cultural Heritage Microbial Deterioration. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1542, 10.3390/microorganisms8101542.

- Sandra Lo Schiavo; Filomena De Leo; Clara Urzì; Present and Future Perspectives for Biocides and Antifouling Products for Stone-Built Cultural Heritage: Ionic Liquids as a Challenging Alternative. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 6568, 10.3390/app10186568.

- Claudia Gazzano; Sergio E. Favero-Longo; Paola Iacomussi; Rosanna Piervittori; Biocidal effect of lichen secondary metabolites against rock-dwelling microcolonial fungi, cyanobacteria and green algae. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2013, 84, 300-306, 10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.05.033.

- Daniela Isola; Flavia Bartoli; Paola Meloni; Giulia Caneva; Laura Zucconi; Black Fungi and Stone Heritage Conservation: Ecological and Metabolic Assays for Evaluating Colonization Potential and Responses to Traditional Biocides. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 2038, 10.3390/app12042038.

- Marwa Ben Chobba; Maduka L. Weththimuni; Mouna Messaoud; Clara Urzi; Jamel Bouaziz; Filomena De Leo; Maurizio Licchelli; Ag-TiO2/PDMS nanocomposite protective coatings: Synthesis, characterization, and use as a self-cleaning and antimicrobial agent. Progress in Organic Coatings 2021, 158, 106342, 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106342.

- Filomena De Leo; Alessia Marchetta; Gioele Capillo; Antonino Germanà; Patrizia Primerano; Sandra Lo Schiavo; Clara Urzì; Surface Active Ionic Liquids Based Coatings as Subaerial Anti-Biofilms for Stone Built Cultural Heritage. Coatings 2020, 11, 26, 10.3390/coatings11010026.

- Filomena De Leo; Alessia Marchetta; Gioele Capillo; Antonino Germanà; Patrizia Primerano; Sandra Lo Schiavo; Clara Urzì; Surface Active Ionic Liquids Based Coatings as Subaerial Anti-Biofilms for Stone Built Cultural Heritage. Coatings 2020, 11, 26, 10.3390/coatings11010026.