Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Zhiyin Song and Version 2 by Jessie Wu.

Mitochondrion harbors its own DNA (mtDNA), which encodes many critical proteins for the assembly and activity of mitochondrial respiratory complexes. mtDNA is packed by many proteins to form a nucleoid that uniformly distributes within the mitochondrial matrix, which is essential for mitochondrial functions. Defects or mutations of mtDNA result in a range of diseases. Damaged mtDNA could be eliminated by mitophagy, and all paternal mtDNA are degraded by endonuclease G or mitophagy during fertilization.

- mtDNA

- mitophagy

1. mtDNA Structure

1. mtDNA Structure

The structure of mtDNA is significantly different from that of nDNA; however, similar to the bacterial chromosome, mtDNA forms a closed circle doubled-stranded DNA in nearly all metazoa [1][19]. The sense strand and antisense strand of mtDNA are named a heavy (H) strand and a light (L) strand. In human cells, mtDNA consists of 16,569 base pairs, and encodes 37 genes, including 13 polypeptides, two ribosomal RNAs, and 22 tRNAs [2][3][6,20]. One polypeptide (ND6) and eight tRNAs are located on the L strand; the other 12 polypeptides, two rRNAs, and 14 tRNAs are encoded by the H strand. mtDNA also contains a noncoding region, which is called a displacement loop (D-loop), and harbors almost all the known mtDNA replication and transcription [4][21]. The 13 polypeptides are the core subunit of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes I, III, IV, and V, and are essential for OXPHOS activity. Mitochondrial rRNAs and tRNAs constitute a machine for the synthesis of 13 peptides.

2. mtDNA Mutation and Human Diseases

2. mtDNA Mutation and Human Diseases

mtDNA is susceptible to be attacked by oxygen free radicals, and tends to develop somatic mutations due to the lack of protection by histones [5][6][22,23]. mtDNA is located in the mitochondrial matrix, and is in close proximity to the respiratory chains [3][6][20,23], which are the main source of the reactive oxygen species (ROS). mtDNA encodes the core subunit of OXPHOS that produces the vast majority of cellular ATP. Excessive mtDNA mutations could result in the dysfunction of OXPHOS, which subsequently leads to diseases associated with mitochondrial function. In fact, many diseases have been found to be associated with mtDNA mutations, and most maternal mtDNA diseases can transmit to their offspring due to the feature of matrilineal inheritance in mtDNA [7][24].

Since the first human mtDNA mutation was described in 1988 [8][25], several mtDNA mutations and the associated mtDNA diseases have been identified. The obvious feature of mtDNA diseases is characterized by the presence of various neurological features [1][19]. Kearns–Sayre syndrome (KSS) and Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) are the early identified syndromes associated with mtDNA mutation [9][10][26,27]. KSS is associated with progressive myopathy, ophthalmoplegia, and cardiomyopathy, which is caused by single, large-scale deletions [8][9][25,26]. LHON is an optic neuropathy that is caused by mtDNA point mutations (m.3460G > A, m.11778G > A, and m.14484T > C) [10][11][12][27,28,29]. The point mutation of ATP6 (m.8993T > C or 8993T > G), which is the core subunit of OXPHOS protein complex V, contributes to Leigh syndrome (LS), which is also known as subacute necrotizing encephalomyelopathy [13][14][30,31]. Myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF), which is a severe neuromuscular disorder accompanied by symptoms of myoclonic epilepsy, myopathy, dementia, or ataxia, is caused by the point mutation of tRNA [15][16][32,33].

Additional, mtDNA mutations are associated with other human diseases, including diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and cancer. Diabetes is one of the most common chronic disorders. mtDNA point mutations (m.3242A > G) and the 10.4-kb deletion of mtDNA are associated with diabetes and deafness, and the mutations are maternally inherited [17][18][34,35]. It is hypothesized that mtDNA mutations accumulate over time, which plays a central role in the process of aging and related neurodegeneration [1][19]. In fact, there is already a lot of evidence that demonstrates that mtDNA mutations are indeed associated with aging, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Recent evidence suggests that dysregulated mitochondrial dynamics and mutations caused by mtDNA replication can lead to aging, and the increasing mtDNA mutation rates increase the aging rate and provide an aging clock [19][36]. A high level of deleted mtDNA has been found in the substantia nigra neurons of patients with aging and Parkinson’s disease [20][37]. Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by the loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain and the accumulation of α-synuclein [21][38]. Alzheimer’s disease, another neurodegenerative disease, is associated with heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations [22][39]. In addition, tumors and mtDNA mutations are also inextricably linked. mtDNA mutations contribute to tumorigenicity. ND3 gene mutation (m.G10398A) had been found to increase the risk of invasive breast cancer in African-American women [23][40]. Further data demonstrate that both germ-line and somatic mtDNA mutations contribute to prostate cancer, and about 11% of all prostate cancer patients harbored mt-CO1 (mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase I) mutations [24][41]. Additionally, the pathogenic mtDNA ATP6 T8993G germ-line mutation was found to generate tumors that were seven times larger than the wild type (T8993T) [24][41].

3. mtDNA Distribution

3. mtDNA Distribution

The mitochondrion is a highly dynamic double-membrane organelle that forms a well-distributed network in the majority of mammalian cell types. mtDNA is located in the mitochondrial matrix, associated with the mitochondrial inner membrane, and distributed throughout the mitochondrial network [3][20]. Each mitochondrion contains one or more mtDNA molecules [2][6]. In proliferative cells, mtDNA is replicated, separated, and distributed equally to daughter cells, which are dependent on mitochondrial dynamics. In addition, the mitochondrial membrane structure and membrane composition are also involved in mtDNA attachment and distribution [3][20].

3.1. mtDNA Distribution and Mitochondrial Dynamics

3.1. mtDNA Distribution and Mitochondrial Dynamics

Mitochondria continuously undergo fusion and fission, which are essential for cell metabolic activities, as well as mtDNA distribution in mitochondria. Mitochondrial fusion and fission, the two opposite processes, are both mediated by large GTPases proteins, which are conserved in yeast, flies, and mammals [25][42]. Mitochondrial fusion is mediated by three GTPases proteins: Mitofusin 1 (Mfn1), Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), and Optic Atrophy 1 (OPA1) [26][27][43,44]. As the feature of a double membrane, mitochondrial fusion is a two-step process requiring outer-membrane fusion followed by inner-membrane fusion [28][1]. Mfn1 and Mfn2 regulate the mitochondrial outer membrane fusion, and OPA1 is involved in mitochondrial inner membrane fusion [29][45]. A deficiency of fusion results in severe mitochondrial fragmentation and is associated with a range of human diseases [30][31][46,47]. The mutation of Mfn2 causes Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2A in human, which is a common inherited peripheral neuropathy [31][32][47,48]. The dysfunction of OPA1 is associated with dominant optic atrophy (DOA), which is an optic neuropathy caused by the degeneration of retinal ganglion cells [28][33][34][1,49,50]. Mitochondrial fission is regulated by Drp1, a cytosolic dynamic protein, which is recruited to mitochondria from the cytosol, forms spirals around the mitochondria, and then constricts it by hydrolyzing GTP to mediate mitochondrial scission [28][35][1,51].

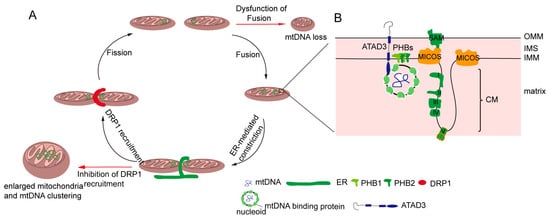

Mitochondria and mtDNA are highly dynamic [36][52]. mtDNA are distributed throughout the mitochondrial network [37][53], which is important for the uniform distribution of mtDNA-encoded proteins in mitochondria. Mitochondrial dynamics greatly influence the distribution and maintenance of mtDNA [38][54]. A deficiency in mitochondrial fusion has a profound effect on mtDNA (Figure 1A). It has been demonstrated Mfn1 and Mfn2 conditional knock-out mice in muscle result in muscle atrophy, mitochondrial dysfunction, and severe mtDNA depletion [39][55]. OPA1 mediates the fusion of the mitochondrial inner membrane, and regulates cristae remodeling and cytochrome c release during apoptosis [40][41][42][56,57,58]. In addition, OPA1 mutations in patients lead to multiple deletions of mtDNA in their skeletal muscle [43][59], and one isoform of OPA1 was associated with mtDNA replication, distribution, and maintenance [44][60]. Mitochondrial fission also plays an essential role in mtDNA distribution. The deficiency of mitochondrial fission caused by the loss of Drp1 leads to hyperfused mitochondria and enlarged mtDNA nucleoids characterized by mtDNA accumulation [38][45][46][54,61,62]. Mitochondrial fusion promotes complementation between two mitochondria, including mtDNA [25][47][42,63]; mitochondrial fission separates mtDNAs into two divided mitochondria, and also contributes to a chance for a mitochondrion to re-fuse with another part of the mitochondrial network (Figure 1A). Therefore, mtDNA are distributed throughout the network by continuous fusion and fission [38][54].

Figure 1. Regulation of the distribution of mitochondria DNA (mtDNA). (A) Mitochondrial dynamics regulate mtDNA. Mitochondrial fission and mtDNA segregation happened synchronously, and occur at the ER and mitochondrial contact site. Upon fission, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) wraps the mitochondria, and then the cytosolic dynamic protein Drp1 is recruited to mediated mitochondria division. Blocking the fission leads to enlarged mitochondria and an mtDNA cluster. Mitochondrial fusion allows for two mitochondrial exchange substances, including mtDNA. The dysfunction of fusion leads to mtDNA deletion. (B) The mitochondrial inner membrane is involved in mtDNA distribution. Certain mitochondrial inner membrane proteins such as prohibitins and ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3 (ATAD3) are mtDNA-binding proteins. In addition, mtDNA nucleoid contacts with the mitochondrial cristae junction, and MICOS complex and Sam50, which are involved in the maintenance of the cristae structure, regulate mtDNA distribution.

The distribution of mtDNA is tightly interlinked with the dynamics of mitochondria, but the mechanisms of mtDNA distribution throughout the mitochondrial network are poorly understood. Recent evidence shows the close proximity between mtDNA and the sites of Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission, which is highly conserved in yeast and mammalian cells [45][48][49][61,64,65]. In yeast and mammalian cells, mitochondrial division occurs at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria contact sites (Figure 1A), in which the ER wraps around the mitochondria; then, Drp1 is recruited and assembled around mitochondria [50][51][66,67]. Moreover, the majority of ER-linked mitochondrial division events occur adjacent to nucleoids [3][49][20,65]. Following mtDNA replication, ER-linked mitochondrial fission occurs between the replicated mtDNAs, which locate at newly generated mitochondrial tips after scission [37][48][49][53,64,65]. Localizing mtDNA to the newly formed mitochondrial tips could transport mtDNA to the distal parts of cell, and further fuse with other mitochondria to drive mtDNA distribution. The mechanism can explain how mtDNA is equivalently distributed in cells and how mtDNA is distributed into mitochondria following mtDNA replication.

3.2. mtDNA Distribution and Inner Membrane Structure

3.2. mtDNA Distribution and Inner Membrane Structure

The structure of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is divided into two morphologically and presumably functionally distinct subdomains: the inner boundary membrane (IBM), which is closely opposed to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), and the cristae membrane (CM), which protrudes into the matrix [3][52][20,68]. The IBM comes into close contact with the OM by the protein transport complexes [52][53][54][68,69,70]. The CM is formed by the invaginations of the IBM, and is enriched in respiratory chain complexes and some small molecules and metabolites [52][55][68,71]. There is another substructure of the inner membrane—the cristae junction—that connects the IBM with the CM [56][57][72,73]. It has been reported mtDNA is associated with the IMM, and mtDNA is frequently observed intertwined into cristae [3][20]. Therefore, there may be several IMM factors regulating mtDNA distribution. Indeed, it has been found that the MICOS (mitochondrial contact site and cristae junction organizing system) locates at the cristae junction and is involved in regulating the inner mitochondrial membrane cristae junction [55][58][59][71,74,75]. In yeast, MIC60 (Fcj1) and Mic10 (Mos10), two key components of the MICOS, regulate mtDNA nucleoid size and distribution [60][76]. Deficiencies in the two proteins result in the formation of large mtDNA nucleoids and giant spherical mitochondria [60][76]. Consistently, researchers have found that MIC60 (IMMT) knockdown led to alterations of mitochondrial tubular morphology to giant spherical mitochondria and the disorganization and clustering of nucleoids in mammalian cells (Figure 1A) [61][77]. Sam50, a MICOS-interacting protein in mammalian cells, is located at the outer mitochondrial membrane [62][78]. The loss of Sam50 results in the disorganization of cristae and large spherical mitochondria, and also leads to enlarged mtDNA nucleoids, which protect mtDNA from clearance by mitophagy [63][79]. However, how the mitochondrial inner membrane regulates mtDNA organization and distribution remains unknown. It has been hypothesized that cristae junctions contribute to maintaining proper internal membrane compartmentalization, and the loss of these junctions leads to clustering and the missegregation of mtDNA nucleoids due to the loss of proper compartmental localization of the mtDNA within the mitochondrial tubules [55][71].

3.3. mtDNA Distribution and Cholesterol

3.3. mtDNA Distribution and Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a composition of lipid rafts, and contributes to being a dynamic glue that keeps the raft assembly together [64][65][80,81]. Recent data demonstrate that the human mtDNA–protein complex colocalizes with the cholesterol-rich membrane [66][82]. Additional, cholesterol is also rich at the site of the ER-associated mitochondrial membrane (MAM), which is involved in mtDNA distribution and segregation [3][67][68][20,83,84]. Thus, it is possible that cholesterol is associated with the distribution of mitochondrial nucleoids. ATAD3 (ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3), locating at the mitochondrial inner membrane, is colocalized with mitochondrial nucleoids in mammalian cells by binding to the D-loop of mtDNA (Figure 1B) [69][70][85,86]. A deficiency of ATAD3 in cells results in the disorganization of mitochondrial nucleoids, which is also found in the mouse model and in patients with pathogenic mutations in ATAD3 [71][72][87,88]. Furthermore, ATAD3 is involved in regulating cholesterol metabolism [71][72][87,88]. Therefore, it seems that ATAD3 regulates mtDNA maintenance by regulating cholesterol metabolism.