Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Bryony M. Bowman and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

The UK water industry is subject to a rolling cycle of investment to meet regulatory requirements. Moreover, this sits within the context of a constant state of flux due to the changing climate and political and societal priorities. Therefore, interventions such as improved wastewater treatment (to reduce nutrient levels entering rivers) are likely to experience conditions over the asset life, which vary widely from design parameters. This leads to a cycle of modification and upgrading in order to maintain or improve treatment processes which could include abortive investment.

- sustainability

- water

- UK

- regulation

- justice

1. Introduction

The UK water industry is subject to a rolling cycle of investment to meet regulatory requirements. Moreover, this sits within the context of a constant state of flux due to the changing climate and political and societal priorities. Therefore, interventions such as improved wastewater treatment (to reduce nutrient levels entering rivers) are likely to experience conditions over the asset life, which vary widely from design parameters. This leads to a cycle of modification and upgrading in order to maintain or improve treatment processes which could include abortive investment. In addition to the direct conditions relating to water industry assets, there are also surrounding influences (indirect conditions) that constitute a range of challenges and opportunities and which could unfold in a variety of ways. These factors combine to create an environment of uncertainty within which the water industry must operate. This systematicontent e literature review explores how future uncertainty can be considered through associated decision-support systems, ultimately leading to appropriate interventions being adopted.

2. Sustainability Goals within the UK Water Industry

Sustainability is a concept that is discussed from a range of perspectives. Most frequently, in the realms of sustainable development, the 1987 definition by the United Nations Brundtland Commission is used: ‘Meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ [1][4]. The application of this definition is then further conceptualised as consisting of three pillars—social, economic and environmental [2][5]—as depicted in the visualisation in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Visualisation of sustainability.

Visualisation of sustainability. Reprinted from Purvis et al. [5].

In the global context, discussion of sustainability has led to the 2015 adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [3][6]. Since this agreement, global pressures have escalated around two themes: climate and environmental change; and increasing inequality, both within and between nations [4][7], leading to discussions of justice.

Within infrastructure discussions, goals of robustness and resilience are often considered to be precursors to achieving sustainability and, subsequently, justice [5][6][7][8][8,9,10,11]. Indeed, Sadr [5][8] presents this as a hierarchy of aspiration for which each stage acts as a building block for the next. In this hierarchy, environmental justice can be seen as a specific form of justice in which environmental and social equity are prioritised. Contrastingly, water justice has a tendency to relate to the human experience [9][10][12,13], in particular to the fair and equitable access to water through the discussion and practice of distributive justice.

Within the context of the global provision of water and sanitation, this leads to the question of whether sustainability, environmental justice and water justice are desired goals. Arguably, they could all be, although the outcomes and endpoints vary. In thereis paper, due to the mature status of the UK water industry in the provision of public health needs, environmental justice is proffered as the goal. This is to ensure that the voice of nature is represented alongside the needs of humans, both now and into the future.

Various ownership and regulatory models for water service provision are in place globally, and several studies explore how this may influence the degree to which social equity and environmental goals are incorporated [11][12][13][14][15][16][17][14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. HThis papere does not seek to extend this discussion due to its focus on the UK water industry, and in particular England and Wales.

Somewhat anomalously in the global context, the water industry in England and Wales was privatised in 1989 to stimulate investment from private sources for the continued provision of water and to drive improvements in wastewater treatment [18][19][21,22]. The situation differs across the devolved nations of the UK, so this text will focus on the water industry in England and Wales to provide consistency across the regulatory regime.

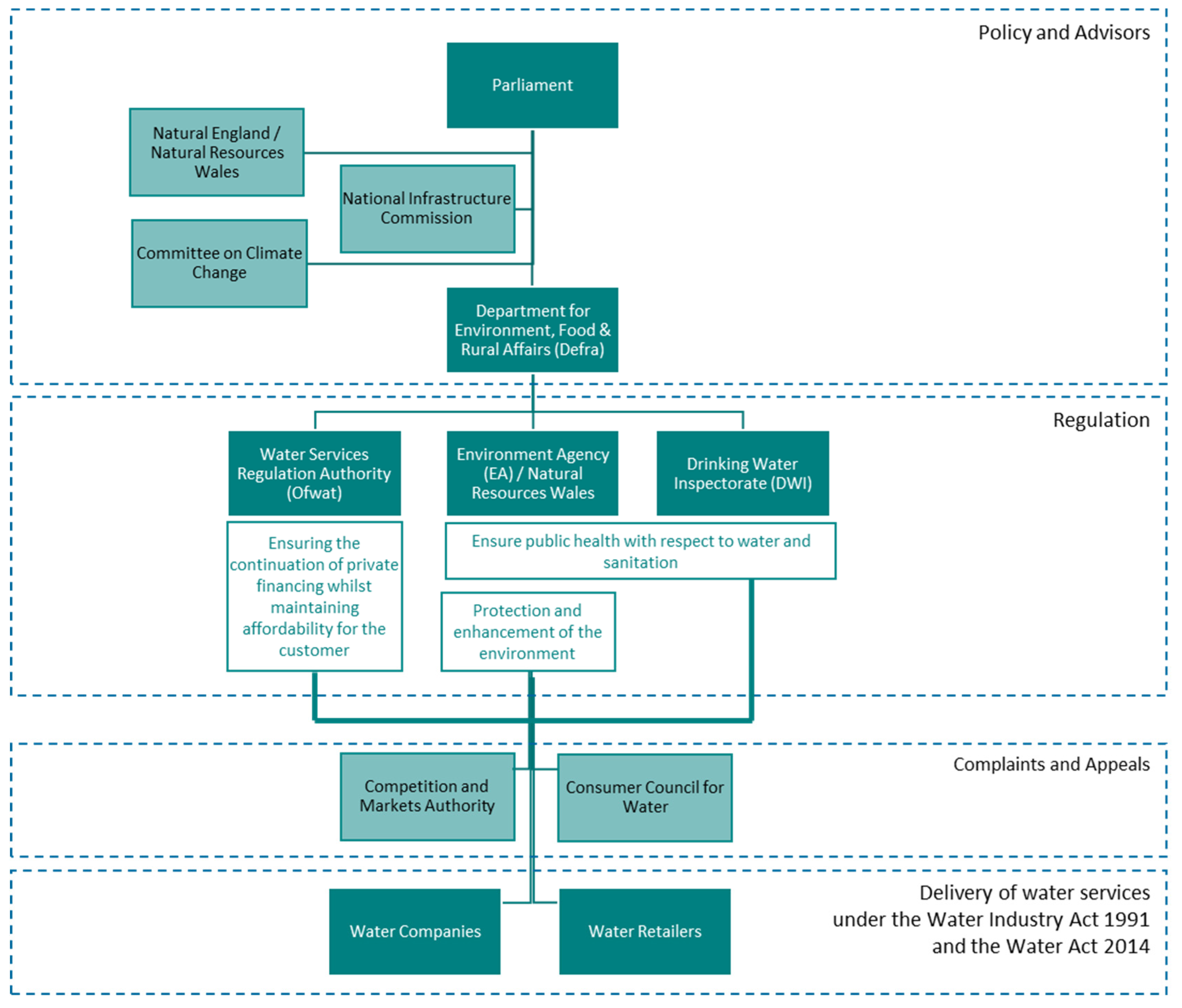

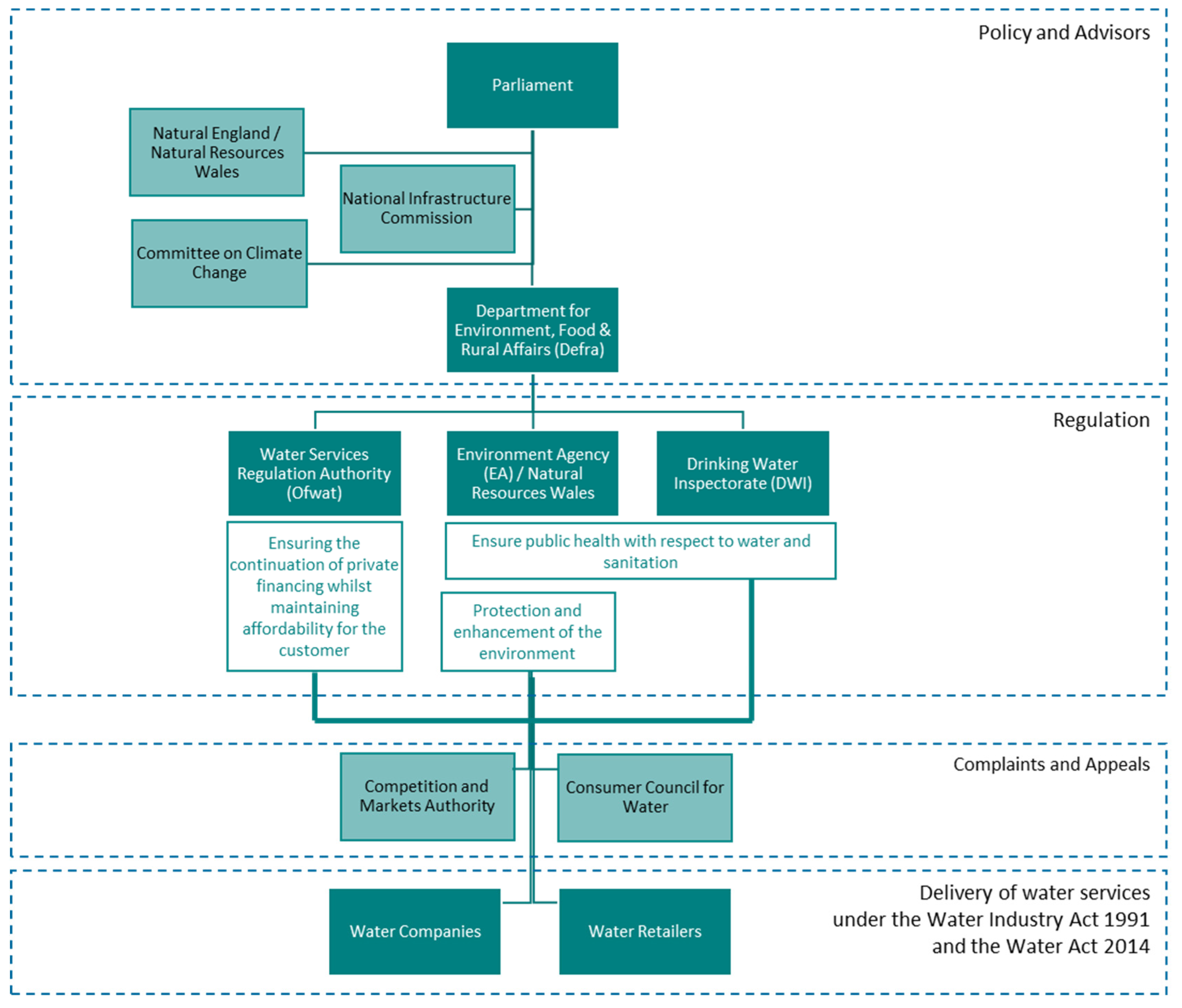

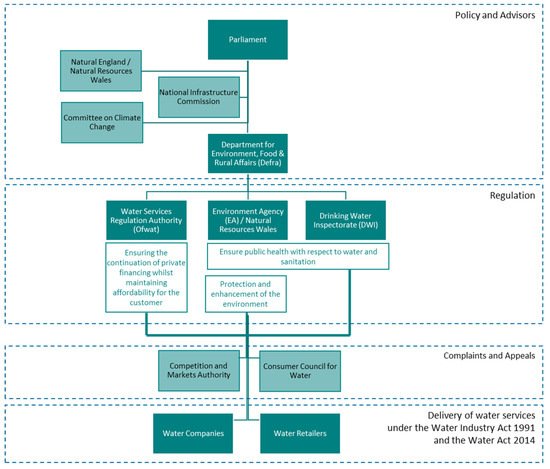

The primary function of the water industry, and specifically licensed water companies, is to perform the statutory duty to provide potable water and sanitation services to the population. Several regulatory bodies focus on complementary aspects of the water industry’s functions. In addition to these regulators, there are several policy and advisory organisations, as well as complaints and appeals bodies, which collectively influence water companies and water retailers (Figure 2). Ofwat, through the Price Review process, is regarded as the means by which Defra is able to influence the direction of the water industry [20][21][23,24].

Figure 2. Regulatory structure of the Water Industry in England. In Wales Natural Resources Wales operates in the equivalent role to the Environment Agency.

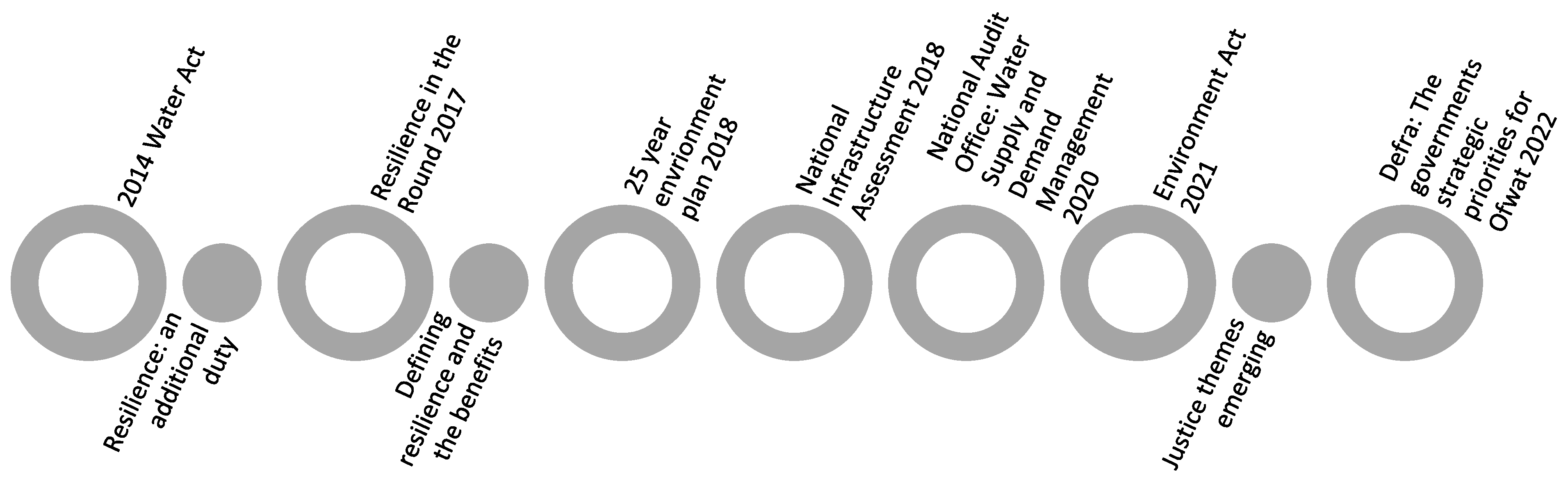

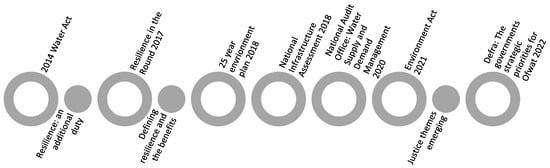

The Water Act 2014 gave Ofwat, and thereby the UK water industry, an additional remit of long-term resilience of water and wastewater services [22][25]. Since then, a number of published government documents have incorporated resilience (Figure 3), which is typically thought of in infrastructure as the ability of a system to efficiently resist, adapt and recover from shocks [23][26]. Ofwat considers resilience in terms of financial, corporate and operational resilience to ensure that water and wastewater services are provided regardless of external disruption [22][25]. The 25-Year Environment Plan [24][27] gives prioritisation to the delivery of long-term resilience in infrastructure, supporting environmental standards with a focus on natural capital and including reference to intergenerational equity, which is echoed in later documents setting the strategic directive for Ofwat [20][21][23,24]. This implies that there is an ambition to move towards achieving justice themes. However, the language is deeply rooted in the provision of a robust and resilient water industry, indicating that although there may be some aspirational movement towards more mature themes, current application is at best tentative. Indeed, guidance for Price Review 2019 focused on providing resilience, with evidence subsequently that this passed into water company business plans for AMP7 [25][28]. The definition of resilience held within these publications, however, is developing to include language which would more typically be associated with environmental and water justice aspirations. This could see a shift in direction to more mature goals; however, unless the language also adapts, it could limit the capacity for change to be accepted and adopted both within and outside the water industry.

Figure 3.

Governmental water industry publications highlighting the references to resilience and environmental justice.

The guidance in Price Review 2024 (PR24) is yet to be fully published, although consultation documents imply that adaptive planning may be featured [26][27][29,30]. Ofwat has recognised the uncertainty facing the water industry and the need for long-term strategies that incorporate adaptation and strive towards a no- or low-regrets approach. To support this, a series of factors are explored, predominantly in isolation, in ‘high’ and ‘low’ states, which are used to stress test water company strategies [27][30]. The water industry’s adoption and development of this approach for PR24 is underway, with the application of scenarios, foresight and justice aspirations within these methods, as yet, unclear.