Ewing sarcoma (ES) is an uncommon cancer that arises in mesenchymal tissues and represents the second most widespread malignant bone neoplasm after osteosarcoma in children. Amplifications in genomic, proteomic, and metabolism are characteristics of sarcoma, and targeting altered cancer cell molecular processes has been proposed as the latest promising strategy to fight cancer. Recent technological advancements have elucidated some of the underlying oncogenic characteristics of Ewing sarcoma.

- Ewing sarcoma

- progression

- targeted therapy

- EWSR1/FLI1

1. Introduction

2. General Consideration: Hallmarks of Cancer

It is known that cancer cells are characterized by a set of features that distinguish them from non-neoplastic cells. The list of cancer hallmarks has been changed and refined over the years since it was first determined [19][18]. In 2022, Hanahan edited and expanded the list [20][19]. Nowadays, the authors of the concept propose nine hallmark capabilities: sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, activating invasion and metastasis, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, resisting cell death, avoiding immune destruction, deregulating cellular energetics, and unlocking phenotypic plasticity. In addition to these, there are also four enabling characteristics, by which cancer cells and tumors can adopt these functional capabilities: genome instability and mutations, tumor-promoting inflammation (with the effect of senescent cells), and non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming, and polymorphic microbiomes. ES is, in contrast to most other sarcoma types, genetically stable, but the specific chromosomal translocation [11], for example, EWS-FLI1, is necessary for Ewing sarcoma tumorigenicity [21][20]. As shown earlier by Stolte et al. [21][20] FET tumors, besides gene fusion, are also characterized by wild type p53, suggesting a dependence of such tumors on DNA damage therapeutic stress, stabilized by p53 signaling. The only protein product of this gene can provide the transformation of cellular processes and the acquisition of hallmarks of cancer.3. Molecular Targets for ES Therapy

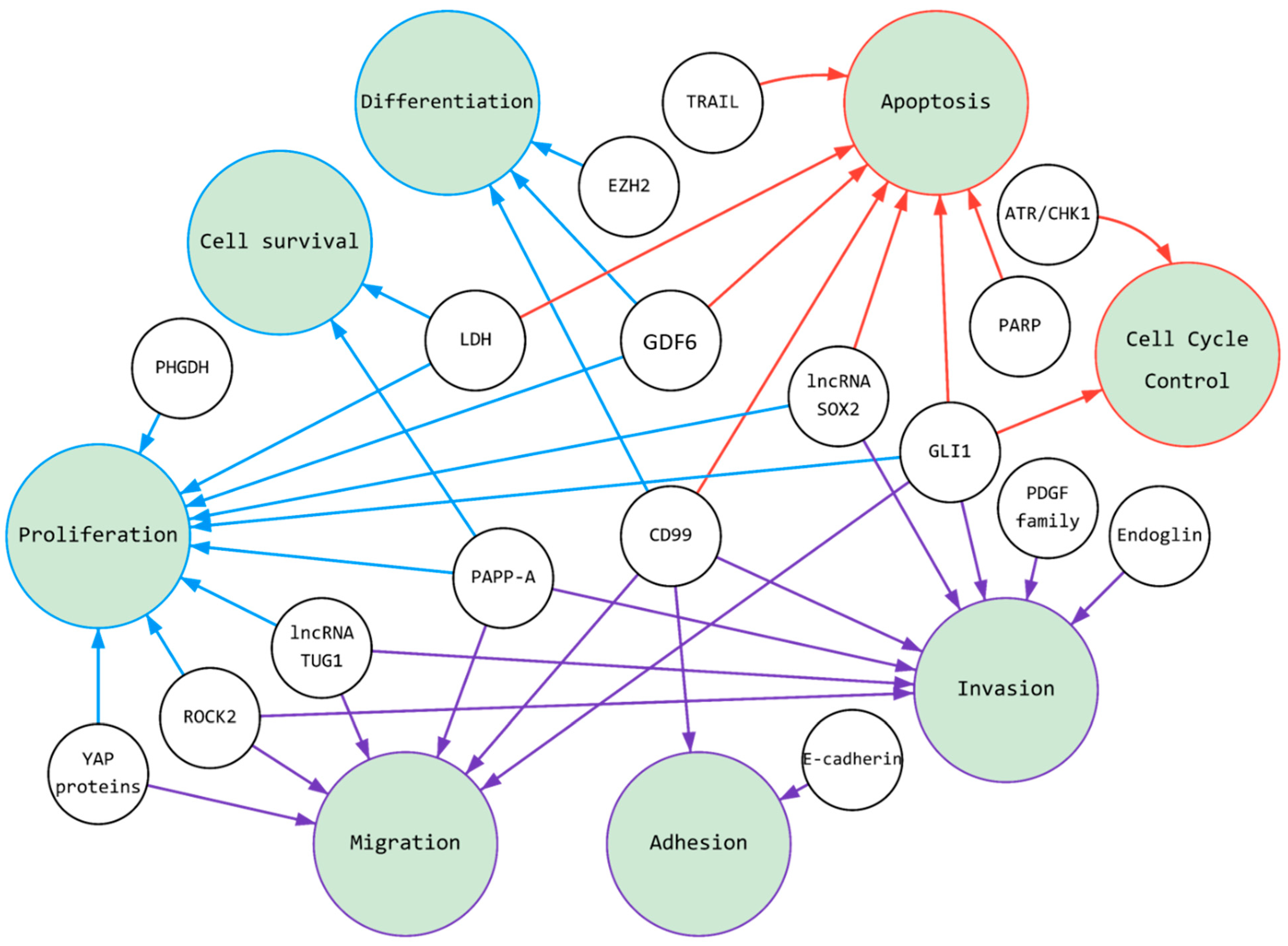

The two most common fusion proteins (EWSR1/FLI1 and EWSR1/ERG) [17] are involved in several cell signaling and regulatory pathways (Graphical Abstract). These fusion proteins usually act as transcription factors. For instance, Boulay et al. [22][21] identified a chromatin-binding factor (BAF) that interacts with EWSR1/FLI1 to activate gene expression in ES tumor cells and phenotypical changes. On the other hand, oncoprotein fusion can induce target genes via a partnership with GGAA microsatellites, as active enhancers [23][22] or by binding to RNA. Important discoveries in recent years have shown that major fractions of the ES fusion proteins bind to the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex in tumor cells and that leads to the deregulation of gene expression, such as IGF-1 signaling [24][23] and epigenetic programming [15,16][15][16] towards retaining mesenchymal stem cell plasticity [25][24]. Blockade of these fusion proteins may be ideal for therapeutic targets. The feasibility of EWSR1/FLI1 targeting for ES therapy has been shown preclinically using chemical inhibitors [26,27,28][25][26][27] and siRNA technology (Bertrand et al. [29][28] Gauthier et al. [30][29] and Cervera et al. [31][30]) and via chemical targeting of EWSR1/FLI1 oncogenic fusion with chemical inhibitors [32][31]. Despite affecting Ewing sarcoma cell viability, multiple reports reveal induction of resistance factors contributing to the tumor’s survival and therapy escape [33,34,35][32][33][34]. Given this problem, it seems prudent to consider the combination of inhibitors against EWSR1/FLI1 or EWSR1/ERG with additional targeted therapies [36,37][35][36] that might overcome tumor cells’ resistance to the monotherapy and might demonstrate a less adverse effect due to dose reduction. One such drug is YK-4-279, a drug candidate active in downregulating transcription of EWS/FLI1 [38][37]. At the same time, YK-4-279 has been shown to inhibit ERG and ETV1 transcription in prostate cancer cells [39][38], therefore, it might also be active against Ewing sarcoma cells with commonly and less commonly presented fusion in the tumors with Ewing sarcoma.3.1. Targeting of ES Pressure on Adhesion, Migration, and Invasion

Like most cancer types, the prognosis for ES patients with localized disease is much better than for patients with metastatic disease [40][39]. A major obstacle in the battle against metastatic disease continues to be an insufficient understanding of underlying processes; specifically, what processes, such as metabolic and others, drive cell adhesion, migration, and invasion during metastases. Adhesion proteins, such as E-cadherin are regarded as tumor suppressors. The low level of epithelial proteins is associated with spheroid formation and migration [41][40]. The migration of cancer cells to new niches is a fundamental process underlying metastasis [42][41]. There are two main types of cancer migration; mesenchymal and amoeboid; each is dependent on complex intracellular signaling that governs the actin cytoskeleton. Actin is involved in several pathways, including Rho/Rac GTPases and the Hippo-pathway, which culminate in the transcriptional regulation of cytoskeletal and growth-promoting genes, respectively. The mesenchymal cell migration of sarcomas can involve both single cells and cells in chains [43][42]. For successful metastasis, migration is followed by invasion into secondary locations [44][43]. Cadherins are vital for the formation of cell-cell contacts. During tumor progression, E-cadherin expression is lost, which permits epithelial to mesenchymal transition, anchorage-independent growth, and spheroid formation [45][44]. Studies have shown that loss of E-cadherin promotes resistance to treatment [40][39] and acquisition of a mesenchymal-like phenotype in vitro. Ex vivo studies have shown that the increased expression of E-cadherin is associated with improved clinical outcomes in several types of sarcomas [46][45]. Thus, E-cadherin upregulation in ES cells is mediated by epigenetics [47][46], or by small molecules like MIL327 [40][39] or RNA interference to metalloproteinase type 9 (MMP9) [48][47]. Besides induction of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)-developed cell signaling, ES metastasis requires cell migration and blood vessel invasion [49][48]. The Rho-associated kinases, ROCK1 and ROCK2 have been implemented in the regulation of metastases using various in vitro and in vivo models. Data by Roberto et al. [49][48] showed a positive correlation between miR-139-5p and ROCK1, where restoration of miR-139-5p impaired ES migration and invasion. Another approach is the application of ROCK2 inhibitors, such as SR3677 and hydroxyfasudil, in SK-ES-1 cells [42][41] to demonstrate an opportunity for simultaneous targeting of heterogenic ES cells. The TGF-β and PDGF pathways play important roles in ES plasticity and tumor progression. The TGF-β co-receptor endoglin is routinely expressed by malignant cells, and it is associated with the upregulation of bone morphogenetic protein, integrin, focal adhesion kinase, and phosphoinositide-3-kinase signaling, which together work in concert to maintain tumor cell plasticity [43,83][42][49]. Like TGF-β, the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) pathway aids in maintaining a cancer stem cell-like phenotype in ES, but more notably, is involved in ES tumor neovascularization [84][50]. Importantly PDGF ligands and/or receptors are frequently upregulated in ES [66,85][51][52] and their expression correlates with the activity of the EWSR1/FLI1 fusion [86][53] in sarcoma tissues. Overall, the pathways involved in ES cellular invasion and migration are complex, and future work is needed to design an effective multitargeted approach against ES tumor cells [87][54]. These genes play a key role in several tumor processes for ES, especially in adhesion, migration, and invasion (Table 1). The regulation of these processes in a tumor is the first step toward the formation of a lesion secondary tumor growth-metastasis from a localized tumor. Metastasis is associated with poor clinical outcomes for patients, while the treatment of localized tumors currently has a relatively high success rate, it could be as high as 70% [18][55]. Therefore, these genes as targets for therapy are especially vital.|

Targetable Molecules |

Main Pathways |

Tumor Effects |

|---|---|---|

|

CD99 |

IGF-1R and RAS-Rac1 signaling |

Induces caspase-independent cell death, endocytosis, cell aggregation, micropinocytosis, cell adhesion, migration, invasion, metastasis, differentiation |

|

GDF6 |

GDF6 prodomain signaling pathway |

Cell proliferation, tumor growth, differentiation, apoptosis |

|

E-cadherin |

MAPK Pathway |

Anchorage-independent growth and spheroid formation, cell-cell adhesion |

|

Endoglin |

TGFβ signaling |

Tumor cell plasticity, patient survival, invasion, anchorage-independent growth, progression of aggressive tumors |

|

EZH2 |

Epigenetic |

Cell differentiation, phenotypic heterogeneity, self-renewal |

|

GLI1 |

Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway |

Cell proliferation, cell cycle control, apoptosis, cell viability, metastasis, invasion, migration, clonogenicity |

|

PDGF family members |

PDGF pathway |

Self-renewal, invasion, chemotherapy resistance, primary tumor growth, metastasis, drug resistance, poor clinical outcome |

|

ROCK2 |

RhoA-ROCK pathway |

Migration, invasion, proliferation, clonogenic capacity, tumor growth |

|

YAP proteins |

YAP/TAZ pathway, Hippo signaling, WNT/β-catenin signaling |

Migration, cell proliferation, metastasis, anchorage-independent colony formation |

|

PAPP-A |

IGF signaling |

Cell proliferation, migration, cell survival, tumor growth, invasion, metastasis |

|

PARP family |

DNA repair, replication |

Apoptosis |

|

TRAIL |

TRAIL-pathway |

Induces caspase-independent cell death, apoptosis |

|

ATR/CHK1 |

ATR-CHK1 pathway |

Cell cycle regulation, cell cycle arrest |

|

LDH |

aerobic glycolysis |

Cell proliferation, apoptosis, tumor growth, cell survival |

|

PHGDH |

Serine synthesis |

Cell proliferation |

|

lncRNA SOX2 |

WNT/β-catenin signaling |

Cell proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, tumor growth |

|

lncRNA TUG1 |

TUG-miR-145-5p-TRPC6 pathway |

Cell proliferation, migration, invasion |

3.2. Targeting of Ewing Sarcoma Cells with a Focus on Proliferation, Cell Differentiation, and Cell Survival

Metastatic progression requires the migration and invasion of cancer cells to reach distant tissues. However, for malignant neoplasms to spread beyond their primary tumor, they must adapt and thrive in a new niche. In general, cancer cells are characterized by unlimited time spent on cell division coupled with high survivability [88][56]. The mechanism for preserving these cells in a poorly differentiated state is elaborate. Mutations and epigenetic changes trigger unregulated mitotic cycles, allowing cells to become insensitive to growth-inhibitory signals, and capable of evading programmed cell death. Cell cycle progression and cell division, cell death, and cellular senescence determine cell proliferation in a broad sense. The expression of the ES fusion gene alters the expression of over 500 downstream targets, which collectively block differentiation and drive proliferation [89][57]. For example, EWSR1/FLI1 regulates several genes, including IGF-1, Homeobox protein Nkx (NKX2), T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK), SRY-Box Transcription Factor 2 (SOX2), and Enhancer Of ZesteHomolog2 (EZH2) [90][58]. It is worth noting that EWS-FLI1 binds to the EZH2 promoter to activate embryonic tumor stem cell growth and metastatic spread [91][59]. These targets can be used in the treatment of Ewing sarcoma. It is well-known that several cancers [99,100][60][61] heavily rely upon glycolysis rather than oxidative metabolism since it provides metabolic plasticity to fuel tumor heterogeneity [101,102][62][63]. Ewing sarcoma is one tumor type [103][64] where a predominant fusion protein, EWS/FLI1, regulates glucose consumption as well as gene expression of glycolytic enzymes, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [32][31]. It has been shown recently that depletion of lactate dehydrogenase-A (LDHA) inhibits proliferation of ES cells and induces apoptosis, impacting tumor cell viability both in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, for various cancers, a growing number of important regulators are being discovered within one group of molecules: long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [104][65]. LncRNAs often increase cancer cell survival, proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion [104,105,106][65][66][67]. Their elevated expression contributes to the progression of the sarcoma. It was described, for example, for lncRNA taurine upregulated gene 1 (TUG1) [106][67] and lncRNA SOX2 [105][66]. Many of the biological regulatory mechanisms of lncRNAs in Ewing sarcoma are still elusive. Nevertheless, they have been shown to often act as competing endogenous RNAs to regulate other genes expression. In principle, the knockdown of lncRNAs or the selection of inhibitory proteins might help to suppress ES growth [105,106][66][67]. These approaches might be potential therapeutic options for treating Ewing sarcoma. In summary, cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival are important, first of all, in the formation of a tumor in a primary or secondary lesion. These properties of cells are related to some extent to other tumor characteristics (Figure 1), for example, deregulated cellular energetics (Table 1). To regulate this group of genes and their products, EWSR1/FLI1 usually acts as a transcription factor and binds with RNA.

3.3. Targeting of ES: Induction of Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest

The development of fusion event inhibitors to suppress the progression of Ewing sarcoma requires the understanding of multiple cellular processes which became active in the tumor cells. Since kinases are integral to tumor maintenance, intervention directed toward these family members is promising. Both apoptosis and cell division utilize several different kinases, such as ATR and CHK1. ES cells exhibit increased levels of endogenous DNA replicative stress and are sensitive to inhibitors of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), an enzyme that limits the rate of deoxyribonucleotide synthesis. ES cells are also dependent on the ataxia telangiectasia, the rad3-related protein (ATR), and the checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) pathway, which play key roles in orchestrating the cellular response to DNA replication stress for survival [107,108][68][69]. ES tumors are sensitive both in vitro and in vivo to ATR and CHK1 inhibitors as separate agents and in combination with other drugs [107,108,109,110,111][68][69][70][71][72]. The ATR-CHK1 pathway, when activated by DNA replication stress, orchestrates a multifaceted response that arrests cell cycle progression, suppresses the origin of replication, stabilizes replication forks, and promotes fork repair and restart [112][73]. Additionally, one of the enzymes regulating the work of the hereditary apparatus of the cell is Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in the processes of DNA repair, maintaining the genetic stability of the cell and its programmed death, and as Ewing sarcoma cell lines are frequently defective in DNA break repair, they are susceptible to PARP inhibition [115,116,117][74][75][76]. Inhibition of PARP showed the effectiveness of this approach if cytostatic drugs were used, the effect of which was intensified [118][77]. Growth and differentiation factor 6 (GDF6), also known as bone morphogenetic protein 13 (BMP13), belongs to the TGF-superfamily’s BMP family. GDF6 has become an attractive target since its binding to its own receptor, such as CD99 [41][40]. GDF6 is vital to embryogenesis, particularly to the development of the neural and skeletal systems, and mutations in GDF6 are associated with abnormalities of the skeleton, the eyes [124][78], and other organs [125][79]. GDF6 is highly expressed in ES tumors and cell lines compared to mesenchymal stem cells and cells from other sarcoma subtypes. The anticancer properties of multiple ES-based therapeutic approaches have been extensively studied, often for their antiproliferative effects. The induction of apoptosis has been reported for several cancers, including Ewing sarcoma. However, ES cells are prone to developing treatment resistance, which contributes to disease recurrence [126][80]. Current ES-therapeutic strategies are promising, and the development of new therapeutics and combinations thereof with greater antitumoral properties has been proposed. Previously, TRAIL, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) ligand superfamily (TNFLSF), has been found to induce apoptosis in cancer cells while sparing normal cells [129,130,131][81][82][83]. Multiple in vitro studies have shown that TRAIL and other death receptor agonists [132,133][84][85] are effective against sarcoma cell lines [131,134][83][86] with ES cell lines showing the greatest sensitivity [135][87]. Ubiquitin-specific protease 6 (USP6) may also contribute to the sensitization of ES cells to exogenous IFNs [136][88]. Henrich and colleagues [136][88] speculate that this negative feedback loop involves USP6, which serves to amplify Interferon Gamma (IFN)-mediated sensitivity to TRAIL. Indisputably, the molecular mechanism of TRAIL sensitivity warrants additional investigation to clarify the molecular basis for drug synergy against ES. The metabolism of Ewing sarcoma involves many genes and metabolic pathways that may be potential targets for therapy (Table 1). The effect on some agents can lead to a static effect, and the activation or silencing of others can be expressed as a bright antitumor effect and lead to apoptosis. Some experimental approaches to stimulating cell cycle arrest [137,138,139][89][90][91] or apoptosis [140,141][92][93] in Ewing sarcoma cells showed effectiveness in preclinical settings, and therefore, might hold great promises in future clinical testing.References

- Mer, A.S.; Ba-Alawi, W.; Smirnov, P.; Wang, Y.X.; Brew, B.; Ortmann, J.; Tsao, M.S.; Cescon, D.W.; Goldenberg, A.; Haibe-Kains, B. Integrative Pharmacogenomics Analysis of Patient-Derived Xenografts. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4539–4550.

- Esiashvili, N.; Goodman, M.; Marcus, R.B., Jr. Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2008, 30, 425–430.

- Jawad, M.U.; Cheung, M.C.; Min, E.S.; Schneiderbauer, M.M.; Koniaris, L.G.; Scully, S.P. Ewing sarcoma demonstrates racial disparities in incidence-related and sex-related differences in outcome: An analysis of 1631 cases from the SEER database, 1973–2005. Cancer 2009, 115, 3526–3536.

- Ordonez, J.L.; Osuna, D.; Herrero, D.; de Alava, E.; Madoz-Gurpide, J. Advances in Ewing’s sarcoma research: Where are we now and what lies ahead? Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 7140–7150.

- Kauer, M.; Ban, J.; Kofler, R.; Walker, B.; Davis, S.; Meltzer, P.; Kovar, H. A molecular function map of Ewing’s sarcoma. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5415.

- Clark, M.A.; Fisher, C.; Judson, I.; Thomas, J.M. Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 701–711.

- Cabral, A.N.F.; Rocha, R.H.; Amaral, A.; Medeiros, K.B.; Nogueira, P.S.E.; Diniz, L.M. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: Report of three different and typical cases admitted in a unique dermatology clinic. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92, 235–238.

- Kruse, A.J.; Croce, S.; Kruitwagen, R.F.; Riedl, R.G.; Slangen, B.F.; Van Gorp, T.; Van de Vijver, K.K. Aggressive behavior and poor prognosis of endometrial stromal sarcomas with YWHAE-FAM22 rearrangement indicate the clinical importance to recognize this subset. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24, 1616–1622.

- Coates, S.J.; Ogunrinade, O.; Lee, H.J.; Desman, G. Epidermotropic metastatic epithelioid sarcoma: A potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol 2014, 41, 672–676.

- Lin, P.P.; Wang, Y.; Lozano, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and the Origin of Ewing’s Sarcoma. Sarcoma 2011, 2011, 276463.

- Riggi, N.; Stamenkovic, I. The Biology of Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2007, 254, 1–10.

- Lawlor, E.R.; Lim, J.F.; Tao, W.; Poremba, C.; Chow, C.J.; Kalousek, I.V.; Kovar, H.; MacDonald, T.J.; Sorensen, P.H. The Ewing tumor family of peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors expresses human gastrin-releasing peptide. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 2469–2476.

- O’Regan, S.; Diebler, M.F.; Meunier, F.M.; Vyas, S. A Ewing’s sarcoma cell line showing some, but not all, of the traits of a cholinergic neuron. J. Neurochem. 1995, 64, 69–76.

- Tirode, F.; Laud-Duval, K.; Prieur, A.; Delorme, B.; Charbord, P.; Delattre, O. Mesenchymal stem cell features of Ewing tumors. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 421–429.

- Linden, M.; Thomsen, C.; Grundevik, P.; Jonasson, E.; Andersson, D.; Runnberg, R.; Dolatabadi, S.; Vannas, C.; Luna Santamariotaa, M.; Fagman, H.; et al. FET family fusion oncoproteins target the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e45766.

- Linden, M.; Vannas, C.; Osterlund, T.; Andersson, L.; Osman, A.; Escobar, M.; Fagman, H.; Stahlberg, A.; Aman, P. FET fusion oncoproteins interact with BRD4 and SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex subtypes in sarcoma. Mol. Oncol. 2022.

- Trancau, I.O. Chromosomal translocations highlighted in Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors (PNET) and Ewing sarcoma. J. Med. Life 2014, 7, 44–50.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70.

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46.

- Stolte, B.; Iniguez, A.B.; Dharia, N.V.; Robichaud, A.L.; Conway, A.S.; Morgan, A.M.; Alexe, G.; Schauer, N.J.; Liu, X.; Bird, G.H.; et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 screen identifies druggable dependencies in TP53 wild-type Ewing sarcoma. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 2137–2155.

- Boulay, G.; Sandoval, G.J.; Riggi, N.; Iyer, S.; Buisson, R.; Naigles, B.; Awad, M.E.; Rengarajan, S.; Volorio, A.; McBride, M.J.; et al. Cancer-Specific Retargeting of BAF Complexes by a Prion-like Domain. Cell 2017, 171, 163–178.e19.

- Marchetto, A.; Ohmura, S.; Orth, M.F.; Knott, M.M.L.; Colombo, M.V.; Arrigoni, C.; Bardinet, V.; Saucier, D.; Wehweck, F.S.; Li, J.; et al. Oncogenic hijacking of a developmental transcription factor evokes vulnerability toward oxidative stress in Ewing sarcoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2423.

- Cironi, L.; Riggi, N.; Provero, P.; Wolf, N.; Suva, M.L.; Suva, D.; Kindler, V.; Stamenkovic, I. IGF1 is a common target gene of Ewing’s sarcoma fusion proteins in mesenchymal progenitor cells. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2634.

- Riggi, N.; Suva, M.L.; De Vito, C.; Provero, P.; Stehle, J.C.; Baumer, K.; Cironi, L.; Janiszewska, M.; Petricevic, T.; Suva, D.; et al. EWS-FLI-1 modulates miRNA145 and SOX2 expression to initiate mesenchymal stem cell reprogramming toward Ewing sarcoma cancer stem cells. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 916–932.

- Pattenden, S.G.; Simon, J.M.; Wali, A.; Jayakody, C.N.; Troutman, J.; McFadden, A.W.; Wooten, J.; Wood, C.C.; Frye, S.V.; Janzen, W.P.; et al. High-throughput small molecule screen identifies inhibitors of aberrant chromatin accessibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3018–3023.

- Welch, D.; Kahen, E.; Fridley, B.; Brohl, A.S.; Cubitt, C.L.; Reed, D.R. Small molecule inhibition of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) and histone deacetylase (HDAC) alone and in combination in Ewing sarcoma cell lines. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222228.

- Grohar, P.J.; Woldemichael, G.M.; Griffin, L.B.; Mendoza, A.; Chen, Q.R.; Yeung, C.; Currier, D.G.; Davis, S.; Khanna, C.; Khan, J.; et al. Identification of an inhibitor of the EWS-FLI1 oncogenic transcription factor by high-throughput screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 962–978.

- Bertrand, J.R.; Pioche-Durieu, C.; Ayala, J.; Petit, T.; Girard, H.A.; Malvy, C.P.; Le Cam, E.; Treussart, F.; Arnault, J.C. Plasma hydrogenated cationic detonation nanodiamonds efficiently deliver to human cells in culture functional siRNA targeting the Ewing sarcoma junction oncogene. Biomaterials 2015, 45, 93–98.

- Gauthier, F.; Claveau, S.; Bertrand, J.R.; Vasseur, J.J.; Dupouy, C.; Debart, F. Gymnotic delivery and gene silencing activity of reduction-responsive siRNAs bearing lipophilic disulfide-containing modifications at 2′-position. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 4635–4643.

- Cervera, S.T.; Rodriguez-Martin, C.; Fernandez-Tabanera, E.; Melero-Fernandez de Mera, R.M.; Morin, M.; Fernandez-Penalver, S.; Iranzo-Martinez, M.; Amhih-Cardenas, J.; Garcia-Garcia, L.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, L.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of EWSR1-FLI1 Inactivation by CRISPR/Cas9 in Ewing Sarcoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 3783.

- Yeung, C.; Gibson, A.E.; Issaq, S.H.; Oshima, N.; Baumgart, J.T.; Edessa, L.D.; Rai, G.; Urban, D.J.; Johnson, M.S.; Benavides, G.A.; et al. Targeting Glycolysis through Inhibition of Lactate Dehydrogenase Impairs Tumor Growth in Preclinical Models of Ewing Sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 5060–5073.

- Heisey, D.A.R.; Lochmann, T.L.; Floros, K.V.; Coon, C.M.; Powell, K.M.; Jacob, S.; Calbert, M.L.; Ghotra, M.S.; Stein, G.T.; Maves, Y.K.; et al. The Ewing Family of Tumors Relies on BCL-2 and BCL-XL to Escape PARP Inhibitor Toxicity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1664–1675.

- Palombo, R.; Verdile, V.; Paronetto, M.P. Poison-Exon Inclusion in DHX9 Reduces Its Expression and Sensitizes Ewing Sarcoma Cells to Chemotherapeutic Treatment. Cells 2020, 9, 328.

- Radic-Sarikas, B.; Tsafou, K.P.; Emdal, K.B.; Papamarkou, T.; Huber, K.V.; Mutz, C.; Toretsky, J.A.; Bennett, K.L.; Olsen, J.V.; Brunak, S.; et al. Combinatorial Drug Screening Identifies Ewing Sarcoma-specific Sensitivities. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 88–101.

- Lessnick, S.L.; Ladanyi, M. Molecular pathogenesis of Ewing sarcoma: New therapeutic and transcriptional targets. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2012, 7, 145–159.

- Spriano, F.; Chung, E.Y.L.; Gaudio, E.; Tarantelli, C.; Cascione, L.; Napoli, S.; Jessen, K.; Carrassa, L.; Priebe, V.; Sartori, G.; et al. The ETS Inhibitors YK-4-279 and TK-216 Are Novel Antilymphoma Agents. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5167–5176.

- Lamhamedi-Cherradi, S.E.; Menegaz, B.A.; Ramamoorthy, V.; Aiyer, R.A.; Maywald, R.L.; Buford, A.S.; Doolittle, D.K.; Culotta, K.S.; O’Dorisio, J.E.; Ludwig, J.A. An Oral Formulation of YK-4-279: Preclinical Efficacy and Acquired Resistance Patterns in Ewing Sarcoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 1591–1604.

- Rahim, S.; Minas, T.; Hong, S.H.; Justvig, S.; Celik, H.; Kont, Y.S.; Han, J.; Kallarakal, A.T.; Kong, Y.; Rudek, M.A.; et al. A small molecule inhibitor of ETV1, YK-4-279, prevents prostate cancer growth and metastasis in a mouse xenograft model. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114260.

- Rellinger, E.J.; Padmanabhan, C.; Qiao, J.; Appert, A.; Waterson, A.G.; Lindsley, C.W.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Chung, D.H. ML327 induces apoptosis and sensitizes Ewing sarcoma cells to TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 491, 463–468.

- Zhou, F.; Elzi, D.J.; Jayabal, P.; Ma, X.; Chiu, Y.C.; Chen, Y.; Blackman, B.; Weintraub, S.T.; Houghton, P.J.; Shiio, Y. GDF6-CD99 Signaling Regulates Src and Ewing Sarcoma Growth. Cell. Rep. 2020, 33, 108332.

- Pinca, R.S.; Manara, M.C.; Chiadini, V.; Picci, P.; Zucchini, C.; Scotlandi, K. Targeting ROCK2 rather than ROCK1 inhibits Ewing sarcoma malignancy. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 1387–1393.

- Ehnman, M.; Chaabane, W.; Haglund, F.; Tsagkozis, P. The Tumor Microenvironment of Pediatric Sarcoma: Mesenchymal Mechanisms Regulating Cell Migration and Metastasis. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 90.

- Codman, E.A. The classic: Registry of bone sarcoma: Part I.—Twenty-five criteria for establishing the diagnosis of osteogenic sarcoma. Part II.—Thirteen registered cases of “five year cures” analyzed according to these criteria. 1926. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2009, 467, 2771–2782.

- Jolly, M.K.; Ware, K.E.; Xu, S.; Gilja, S.; Shetler, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Austin, R.G.; Runyambo, D.; Hish, A.J.; et al. E-Cadherin Represses Anchorage-Independent Growth in Sarcomas through Both Signaling and Mechanical Mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 1391–1402.

- Machado, I.; Navarro, S.; Lopez-Guerrero, J.A.; Alberghini, M.; Picci, P.; Llombart-Bosch, A. Epithelial marker expression does not rule out a diagnosis of Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours. Virchows Arch. 2011, 459, 409–414.

- Hurtubise, A.; Bernstein, M.L.; Momparler, R.L. Preclinical evaluation of the antineoplastic action of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and different histone deacetylase inhibitors on human Ewing’s sarcoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2008, 8, 16.

- Sanceau, J.; Truchet, S.; Bauvois, B. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 silencing by RNA interference triggers the migratory-adhesive switch in Ewing’s sarcoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36537–36546.

- Roberto, G.M.; Delsin, L.E.A.; Vieira, G.M.; Silva, M.O.; Hakime, R.G.; Gava, N.F.; Engel, E.E.; Scrideli, C.A.; Tone, L.G.; Brassesco, M.S. ROCK1-PredictedmicroRNAs Dysregulation Contributes to Tumor Progression in Ewing Sarcoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26, 133–139.

- Pardali, E.; van der Schaft, D.W.; Wiercinska, E.; Gorter, A.; Hogendoorn, P.C.; Griffioen, A.W.; ten Dijke, P. Critical role of endoglin in tumor cell plasticity of Ewing sarcoma and melanoma. Oncogene 2011, 30, 334–345.

- Hamdan, R.; Zhou, Z.; Kleinerman, E.S. Blocking SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 downregulates PDGF-B and inhibits bone marrow-derived pericyte differentiation and tumor vascular expansion in Ewing tumors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 483–491.

- Schaefer, K.L.; Eisenacher, M.; Braun, Y.; Brachwitz, K.; Wai, D.H.; Dirksen, U.; Lanvers-Kaminsky, C.; Juergens, H.; Herrero, D.; Stegmaier, S.; et al. Microarray analysis of Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours reveals characteristic gene expression signatures associated with metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 699–709.

- Uren, A.; Merchant, M.S.; Sun, C.J.; Vitolo, M.I.; Sun, Y.; Tsokos, M.; Illei, P.B.; Ladanyi, M.; Passaniti, A.; Mackall, C.; et al. Beta-platelet-derived growth factor receptor mediates motility and growth of Ewing’s sarcoma cells. Oncogene 2003, 22, 2334–2342.

- Zwerner, J.P.; May, W.A. PDGF-C is an EWS/FLI induced transforming growth factor in Ewing family tumors. Oncogene 2001, 20, 626–633.

- Koppenhafer, S.L.; Goss, K.L.; Terry, W.W.; Gordon, D.J. Inhibition of the ATR-CHK1 Pathway in Ewing Sarcoma Cells Causes DNA Damage and Apoptosis via the CDK2-Mediated Degradation of RRM2. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 91–104.

- Van Mater, D.; Wagner, L. Management of recurrent Ewing sarcoma: Challenges and approaches. Onco. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 2279–2288.

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, M.; Luo, Z.; Wen, Z.; Yan, X. The dichotomous role of TGF-beta in controlling liver cancer cell survival and proliferation. J. Genet. Genom. 2020, 47, 497–512.

- Pridgeon, M.G.; Grohar, P.J.; Steensma, M.R.; Williams, B.O. Wnt Signaling in Ewing Sarcoma, Osteosarcoma, and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017, 15, 239–246.

- Ross, K.A.; Smyth, N.A.; Murawski, C.D.; Kennedy, J.G. The biology of ewing sarcoma. ISRN Oncol 2013, 2013, 759725.

- Burdach, S.; Plehm, S.; Unland, R.; Dirksen, U.; Borkhardt, A.; Staege, M.S.; Muller-Tidow, C.; Richter, G.H. Epigenetic maintenance of stemness and malignancy in peripheral neuroectodermal tumors by EZH2. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 1991–1996.

- Sanchez-Sanchez, A.M.; Antolin, I.; Puente-Moncada, N.; Suarez, S.; Gomez-Lobo, M.; Rodriguez, C.; Martin, V. Melatonin Cytotoxicity Is Associated to Warburg Effect Inhibition in Ewing Sarcoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135420.

- Nie, X.; Wang, H.; Wei, X.; Li, L.; Xue, T.; Fan, L.; Ma, H.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Y.D.; Chen, W.D. LRP5 promotes gastric cancer via activating canonical Wnt/beta-catenin and glycolysis pathways. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 192, 503–517.

- Cortese, N.; Capretti, G.; Barbagallo, M.; Rigamonti, A.; Takis, P.G.; Castino, G.F.; Vignali, D.; Maggi, G.; Gavazzi, F.; Ridolfi, C.; et al. Metabolome of Pancreatic Juice Delineates Distinct Clinical Profiles of Pancreatic Cancer and Reveals a Link between Glucose Metabolism and PD-1(+) Cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 493–505.

- van der Schaft, D.W.; Hillen, F.; Pauwels, P.; Kirschmann, D.A.; Castermans, K.; Egbrink, M.G.; Tran, M.G.; Sciot, R.; Hauben, E.; Hogendoorn, P.C.; et al. Tumor cell plasticity in Ewing sarcoma, an alternative circulatory system stimulated by hypoxia. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 11520–11528.

- Dasgupta, A.; Trucco, M.; Rainusso, N.; Bernardi, R.J.; Shuck, R.; Kurenbekova, L.; Loeb, D.M.; Yustein, J.T. Metabolic modulation of Ewing sarcoma cells inhibits tumor growth and stem cell properties. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 77292–77308.

- Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Xiao, B.; Ma, Z.; Huo, H.; Li, W. A seven-lncRNA signature for predicting Ewing’s sarcoma. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11599.

- Ma, L.; Sun, X.; Kuai, W.; Hu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, W.; Lu, X. LncRNA SOX2 overlapping transcript acts as a miRNA sponge to promote the proliferation and invasion of Ewing’s sarcoma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 3841–3849.

- Li, H.; Huang, F.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, H.C.; Dai, M.; Zeng, J. LncRNA TUG1 promotes Ewing’s sarcoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via the miR-199a-3p-MSI2 signaling pathway. Neoplasma 2021, 68, 590–601.

- Goss, K.L.; Koppenhafer, S.L.; Harmoney, K.M.; Terry, W.W.; Gordon, D.J. Inhibition of CHK1 sensitizes Ewing sarcoma cells to the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor gemcitabine. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 87016–87032.

- Gorthi, A.; Romero, J.C.; Loranc, E.; Cao, L.; Lawrence, L.A.; Goodale, E.; Iniguez, A.B.; Bernard, X.; Masamsetti, V.P.; Roston, S.; et al. EWS-FLI1 increases transcription to cause R-loops and block BRCA1 repair in Ewing sarcoma. Nature 2018, 555, 387–391.

- Lowery, C.D.; Dowless, M.; Renschler, M.; Blosser, W.; VanWye, A.B.; Stephens, J.R.; Iversen, P.W.; Lin, A.B.; Beckmann, R.P.; Krytska, K.; et al. Broad Spectrum Activity of the Checkpoint Kinase 1 Inhibitor Prexasertib as a Single Agent or Chemopotentiator across a Range of Preclinical Pediatric Tumor Models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2278–2289.

- Henssen, A.G.; Reed, C.; Jiang, E.; Garcia, H.D.; von Stebut, J.; MacArthur, I.C.; Hundsdoerfer, P.; Kim, J.H.; de Stanchina, E.; Kuwahara, Y.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of PGBD5-induced DNA repair dependency in pediatric solid tumors. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaam9078.

- Koppenhafer, S.L.; Goss, K.L.; Terry, W.W.; Gordon, D.J. mTORC1/2 and Protein Translation Regulate Levels of CHK1 and the Sensitivity to CHK1 Inhibitors in Ewing Sarcoma Cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 2676–2688.

- Saldivar, J.C.; Cortez, D.; Cimprich, K.A. The essential kinase ATR: Ensuring faithful duplication of a challenging genome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 622–636.

- Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Tang, T.; Guo, C. The role of PARP1 in the DNA damage response and its application in tumor therapy. Front. Med. 2012, 6, 156–164.

- Vormoor, B.; Curtin, N.J. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors in Ewing sarcoma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2014, 26, 428–433.

- Stewart, E.; Goshorn, R.; Bradley, C.; Griffiths, L.M.; Benavente, C.; Twarog, N.R.; Miller, G.M.; Caufield, W.; Freeman, B.B., 3rd; Bahrami, A.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair pathway in Ewing sarcoma. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 829–841.

- Vormoor, B.; Schlosser, Y.T.; Blair, H.; Sharma, A.; Wilkinson, S.; Newell, D.R.; Curtin, N. Sensitizing Ewing sarcoma to chemo- and radiotherapy by inhibition of the DNA-repair enzymes DNA protein kinase (DNA-PK) and poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) 1/2. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 113418–113430.

- Bademci, G.; Abad, C.; Cengiz, F.B.; Seyhan, S.; Incesulu, A.; Guo, S.; Fitoz, S.; Atli, E.I.; Gosstola, N.C.; Demir, S.; et al. Long-range cis-regulatory elements controlling GDF6 expression are essential for ear development. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4213–4217.

- Williams, L.A.; Bhargav, D.; Diwan, A.D. Unveiling the bmp13 enigma: Redundant morphogen or crucial regulator? Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2008, 4, 318–329.

- Grunewald, T.G.P.; Cidre-Aranaz, F.; Surdez, D.; Tomazou, E.M.; de Alava, E.; Kovar, H.; Sorensen, P.H.; Delattre, O.; Dirksen, U. Ewing sarcoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 5.

- Lohberger, B.; Bernhart, E.; Stuendl, N.; Glaenzer, D.; Leithner, A.; Rinner, B.; Bauer, R.; Kretschmer, N. Periplocin mediates TRAIL-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human myxofibrosarcoma cells via the ERK/p38/JNK pathway. Phytomedicine 2020, 76, 153262.

- Du, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Ji, G.; Ma, Q.; Liao, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hou, Y. BAY61-3606 potentiates the anti-tumor effects of TRAIL against colon cancer through up-regulating DR4 and down-regulating NF-kappaB. Cancer Lett. 2016, 383, 145–153.

- Hanikoglu, F.; Cort, A.; Ozben, H.; Hanikoglu, A.; Ozben, T. Epoxomicin Sensitizes Resistant Osteosarcoma Cells to TRAIL Induced Apoptosis. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 527–533.

- Subbiah, V.; Brown, R.E.; Buryanek, J.; Trent, J.; Ashkenazi, A.; Herbst, R.; Kurzrock, R. Targeting the apoptotic pathway in chondrosarcoma using recombinant human Apo2L/TRAIL (dulanermin), a dual proapoptotic receptor (DR4/DR5) agonist. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 2541–2546.

- Plummer, R.; Attard, G.; Pacey, S.; Li, L.; Razak, A.; Perrett, R.; Barrett, M.; Judson, I.; Kaye, S.; Fox, N.L.; et al. Phase 1 and pharmacokinetic study of lexatumumab in patients with advanced cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 6187–6194.

- Hennessy, M.; Wahba, A.; Felix, K.; Cabrera, M.; Segura, M.G.; Kundra, V.; Ravoori, M.K.; Stewart, J.; Kleinerman, E.S.; Jensen, V.B.; et al. Bempegaldesleukin (BEMPEG; NKTR-214) efficacy as a single agent and in combination with checkpoint-inhibitor therapy in mouse models of osteosarcoma. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 1928–1937.

- Gamie, Z.; Kapriniotis, K.; Papanikolaou, D.; Haagensen, E.; Da Conceicao Ribeiro, R.; Dalgarno, K.; Krippner-Heidenreich, A.; Gerrand, C.; Tsiridis, E.; Rankin, K.S. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) for bone sarcoma treatment: Pre-clinical and clinical data. Cancer Lett. 2017, 409, 66–80.

- Henrich, I.C.; Young, R.; Quick, L.; Oliveira, A.M.; Chou, M.M. USP6 Confers Sensitivity to IFN-Mediated Apoptosis through Modulation of TRAIL Signaling in Ewing Sarcoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 1834–1843.

- Robles, A.J.; Dai, W.; Haldar, S.; Ma, H.; Anderson, V.M.; Overacker, R.D.; Risinger, A.L.; Loesgen, S.; Houghton, P.J.; Cichewicz, R.H.; et al. Altertoxin II, a Highly Effective and Specific Compound against Ewing Sarcoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 6176.

- Kerschner-Morales, S.L.; Kuhne, M.; Becker, S.; Beck, J.F.; Sonnemann, J. Anticancer effects of the PLK4 inhibitors CFI-400945 and centrinone in Ewing’s sarcoma cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 2871–2883.

- Ma, Y.; Baltezor, M.; Rajewski, L.; Crow, J.; Samuel, G.; Staggs, V.S.; Chastain, K.M.; Toretsky, J.A.; Weir, S.J.; Godwin, A.K. Targeted inhibition of histone deacetylase leads to suppression of Ewing sarcoma tumor growth through an unappreciated EWS-FLI1/HDAC3/HSP90 signaling axis. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2019, 97, 957–972.

- Flores, G.; Everett, J.H.; Boguslawski, E.A.; Oswald, B.M.; Madaj, Z.B.; Beddows, I.; Dikalov, S.; Adams, M.; Klumpp-Thomas, C.A.; Kitchen-Goosen, S.M.; et al. CDK9 Blockade Exploits Context-dependent Transcriptional Changes to Improve Activity and Limit Toxicity of Mithramycin for Ewing Sarcoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 1183–1196.

- Wang, S.; Hwang, E.E.; Guha, R.; O’Neill, A.F.; Melong, N.; Veinotte, C.J.; Conway Saur, A.; Wuerthele, K.; Shen, M.; McKnight, C.; et al. High-throughput Chemical Screening Identifies Focal Adhesion Kinase and Aurora Kinase B Inhibition as a Synergistic Treatment Combination in Ewing Sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4552–4566.