Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by James O'Connell and Version 2 by Jason Zhu.

Ireland is a country with a low incidence of tuberculosis (TB) that should be aiming for TB elimination. To achieve TB elimination in low-incidence countries, programmatic latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) management is important. This requires high-quality latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) screening.

- latent tuberculosis infection

- quality of care

- effectiveness

- equity

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality, despite being preventable [1]. Ending TB is a global priority, as evident by the existence of the World Health Organisation (WHO) End Tuberculosis Strategy [2], which includes a target of a 90% reduction in TB incidence by 2035 (compared with 2015). As well as collaborating globally to achieve this target, the strategy requires all countries to adapt it at a national level. In 2020, there were 57 countries with a low incidence of TB (defined as fewer than 10 cases per 100,000) [1] that, as well as aiming to achieve the End TB Strategy targets, should be aiming to eliminate TB (defined as fewer than 1 case per million) [3], an important step in global aspirations to end the disease. TB in low-incidence countries is characterised by most disease (70–80%) being due to TB reactivation rather than recent transmission [4][5][4,5]. Therefore, identifying latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) among population groups with a high prevalence or risk of reactivation and providing them with preventive care is important to achieve TB elimination in low-incidence countries [3]. Preventive care involves reducing risk factors for TB reactivation, such as smoking or excessive alcohol intake [6], but also providing chemoprophylactic treatment, which is highly effective [7][8][7,8].

Ireland is a high-income European country with a low incidence of TB (5.6 cases per 100,000 in 2019), drug-resistant TB, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/TB coinfection [9]. The incidence of TB is declining, and deaths due to TB are infrequent [9]. Despite being well placed to eliminate TB, Ireland is not on target to do so [3]. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control recommend that low-incidence European countries, such as Ireland, programmatically screen and treat those at-risk of TB for LTBI [6]. At a minimum, this includes people living with HIV; immunosuppressed persons (such as patients on anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha treatment); patients preparing for transplantation; patients with end-stage renal diseases or preparing for dialysis; patients with silicosis; people with pulmonary fibrotic lesions; and contacts of infectious TB cases (based on a risk assessment of their exposure) [3][6][3,6]. In Ireland, TB care is primarily provided by specialists in tertiary centres and regional public health departments. There is no national programmatic approach to LTBI.

If the programmatic management of LTBI is to be an effective approach to eliminating TB in low-incidence countries, then LTBI screening must be of high quality to maximise those at-risk of TB identified for screening who would subsequently benefit from completing preventive treatment [10]. Therefore, evaluations that define, measure, and report screening quality are important. Such evaluations should be performed nationally to be informative for programmatic LTBI management, but also locally to be informative for local service provision [10]. Where deficits in screening quality are identified, health care providers can engage with their patients to understand why, and service quality can be improved. In Ireland, evaluations of LTBI screening are lacking across all at-risk groups, even at a local level [11]. There is a need for LTBI screening evaluations to be performed at service and national levels in Ireland. Without these, or any progress in establishing programmatic LTBI care, TB elimination efforts in Ireland will remain off track.

Framework to Measure the Quality of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Screening

To evaluate quality, it is necessary to apply a framework that defines quality and outlines how it can be measured. A widely used framework for assessing quality is that of the Institute of Medicine [12], which has been adapted by the WHO and used in their framework for quality, as described in Delivering quality health services: a global imperative for universal health [13]. According to the Institute of Medicine, quality of care is defined as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” [12] and can be measured according to six domains; effectiveness, efficiency, equity, timeliness, patient-centredness, and safety (integration was also added to the Institute of Medicine framework by the WHO in their adaptation).

2. Description of Cohort Screened

There were 1681 IGRA tests performed in 1507 patients between 2016 and 2018. Half of those tested (754/1507) were men. The median age of patients at the time their first test was requested was 45 years (interquartile range (IQR) 33–58). Of all patients, 89.1% (1343/1507) were Irish and 10.9% (164/1507) were non-Irish. Overall, 4.8% (73/1507) of patients screened had a positive test. There were 36 patients, all of whom had a negative IGRA, where the outcome of screening could not be extracted from their health care record due to insufficient information. Few patients (1.6% (23/1471) were categorised as having had active TB, 0.5% (7/1471) of patients had a history of previously treated TB infection, and 3.9% (58/1471) of patients, all of whom had a positive IGRA, were categorised as having had LTBI. The prevalence of LTBI was 4% (58/1441, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.1–5.2%). Of those screened for LTBI, patients on immunosuppressive treatment were the largest cohort (95.8% (1164/1215) of patients). Active TB was diagnosed in less than 1% (7/1164) of this cohort. Patients who had an IGRA performed in the context of an investigation for active TB were the second largest cohort. In these patients, a diagnosis of active TB was the outcome of testing in 5.9% (16/270). Among Irish nationals, 83.4% (1251/1500) of tests were performed to screen for LTBI, 15.1% (226/1500) were performed during an investigation for active TB and 1.5% (23/1500) had an unknown indication. Among non-Irish nationals, 61.9% (112/181) of tests were performed to screen for LTBI, 30.4% (55/181) were performed during an investigation for active TB and 7.7% (14/181) had an unknown indication for testing. Those who were non-Irish nationals were more likely than those who were Irish nationals to have an IGRA performed while being investigated for active TB (30.4% (55/181) vs. 15.1% (226/1500), (χ2 (1, n = 1681) = 27.22, p < 0.001)). Patients who were non-Irish were more likely to have a diagnosis of active TB compared with patients who were Irish (6.7% (10/149) vs. 1% (13/1318), odds ratio (OR) 7.2, 95% CI 3.1–16.8, p < 0.001). The prevalence of LTBI in the non-Irish cohort was 8.7% (12/138, 95% CI 4.6–14.7%), compared with a prevalence of 3.5% (46/1303, 95% CI 2.6–4.7%) in the Irish cohort. Patients who were non-Irish were more likely to have LTBI than patients who were Irish (8.7% vs. 3.5%, OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.3–5.0, p < 0.001). When considering patients screened prior to immunosuppressive treatments, which excludes patients investigated for active TB, there was no evidence of an association between LTBI and non-Irish nationality (3.1% (33/1074) vs. 3.8% (3/80) OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.4–4.1, p = 0.737). Among Irish nationals, male sex was a predictor of having LTBI (5.1% vs. 2.0%, OR 2.6, 95% 1.36–5.02, p < 0.005). However, among non-Irish nationals, there was no evidence that male sex predicted having LTBI (10% vs. 7.4%, OR 1.4, 95% 0.42–4.65, p = 0.58). Increasing age predicted having LTBI among both Irish nationals (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.06, p < 0.001) and non-Irish nationals (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.03–1.15, p < 0.05).3. Screening Effectiveness

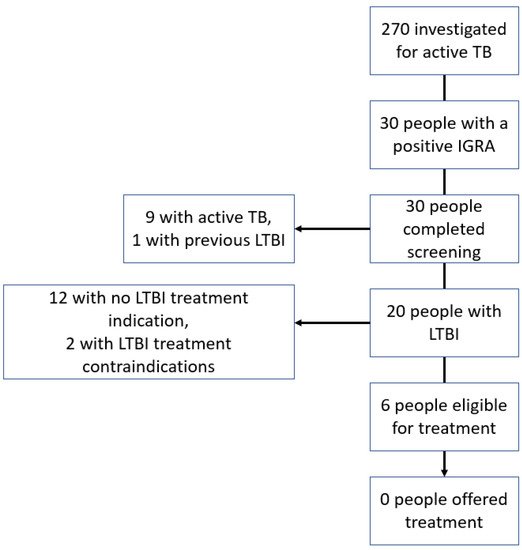

Screening completion occurred in 97% (130/134) of patients in the randomly selected sample and, within this sample, screening completion occurred in 96.6% (114/118) of patients on immunosuppressive treatment, all patients being investigated for active TB (n = 13), both patients that were TB case contacts (n = 2) and the one patient who had radiological findings suggestive of TB infection. Four patients (3%) screened because they were on immunosuppressive treatment did not have chest radiographies performed, and as a result, were not deemed to have completed TB screening. All four patients had a negative IGRA, and no symptoms of TB had been documented. All patients in the random sample (n = 134) with symptoms of TB (n = 14) or an abnormal chest radiograph (n = 13) completed screening. In the entire cohort, all 73 patients with a positive IGRA completed screening. Overall, 40 patients had LTBI, an indication for LTBI treatment with no contra-indication to treatment. Of these, 67.5% (27/40) completed treatment for LTBI. Twenty percent (8/40) of patients eligible for treatment were not offered it by the health care provider, 2.5% (1/40) did not accept treatment when offered, and 10% (4/40) did not complete treatment after initiating it. The number of people screened for LTBI was 1215, of whom 3.1% (38/1215) were diagnosed with LTBI. Of the patients who were not offered, did not accept, or did not complete LTBI treatment (18% (7/38)), none had their immunosuppressant treatment escalated to anti-TNF alpha treatment as planned. None of these patients developed active TB, with a mean follow-up after testing of 1.9 years (standard deviation (SD) = 0.9). Evaluation of the cascade of IGRAs performed during investigations for active TB (Figure 1) identified six patients who did not have active TB, had an indication for LTBI treatment, and no treatment contra-indication. Of these six patients, three were men and three were women. The patient’s ages ranged from 30 to 53 years. All six of these patients were non-Irish and from countries with an intermediate or high TB incidence.

Figure 1.

Cascade of interferon-gamma release assay testing performed during investigation for active tuberculosis.