You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Min Heui Yoo.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous small membrane structures that originate from plasma membranes. Although most EVs have a diameter of 50–200 nm, larger ones are also observed. Generally, particles up to a diameter of 1000 nm are regarded as EVs. They are typically isolated from the conditioned media of cultured cells. The contents of EVs include proteins, mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), and nucleic acids. Each vesicle performs a specific function in transferring biological material(s) to induce biological processes, such as replication, growth, apoptosis, and necrosis.

- Extracellular vesicles

1. Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous small membrane structures that originate from plasma membranes. Although most EVs have a diameter of 50–200 nm, larger ones are also observed. Generally, particles up to a diameter of 1000 nm are regarded as EVs [1,2][1][2]. They are typically isolated from the conditioned media of cultured cells. The contents of EVs include proteins, mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), and nucleic acids [3]. Each vesicle performs a specific function in transferring biological material(s) to induce biological processes, such as replication, growth, apoptosis, and necrosis [4,5,6][4][5][6]. They are also required for cell-to-cell communication to maintain a normal homeostatic state [7]. EVs can be used as cargo carriers in physiological or pathological conditions and are considered biomarkers representing altered normal physiological states [8]. Based on these characteristics, EVs can be used for diverse purposes, from cosmetic to therapeutic applications. The main advantage of EVs is their limited adverse effects when used for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes, because they are composed of cell-derived materials and because of their potential for targeted cell delivery [9]. In addition, compared to cells, they are easier to store and transport.

The first EV that was identified is involved in transferrin receptor elimination, which plays a role in the maturation of reticulocytes, as reported by Harding et al. in 1983 [10]. The authors demonstrated the release of multi-vascular endosomes from the plasma membrane by exocytosis in rat reticulocytes. EVs can be found in all types of body fluids, such as plasma [11], bile [12], breast milk [13], urine [14], ascites, and cerebrospinal fluid [15]. Thus, these vesicles show potential for revealing abnormal conditions in various organs. EVs from the blood can be used to detect inflammation or an aberrant immune system, whereas those from breast milk can be utilized to diagnose breast conditions [16]. Halvaei et al. reported that EVs can be used for the diagnosis of various cancers using cancer-specific miRNAs [17].

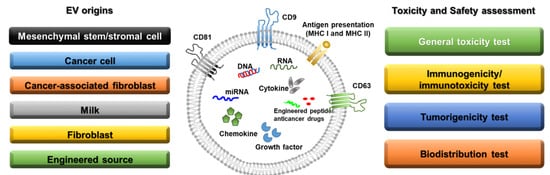

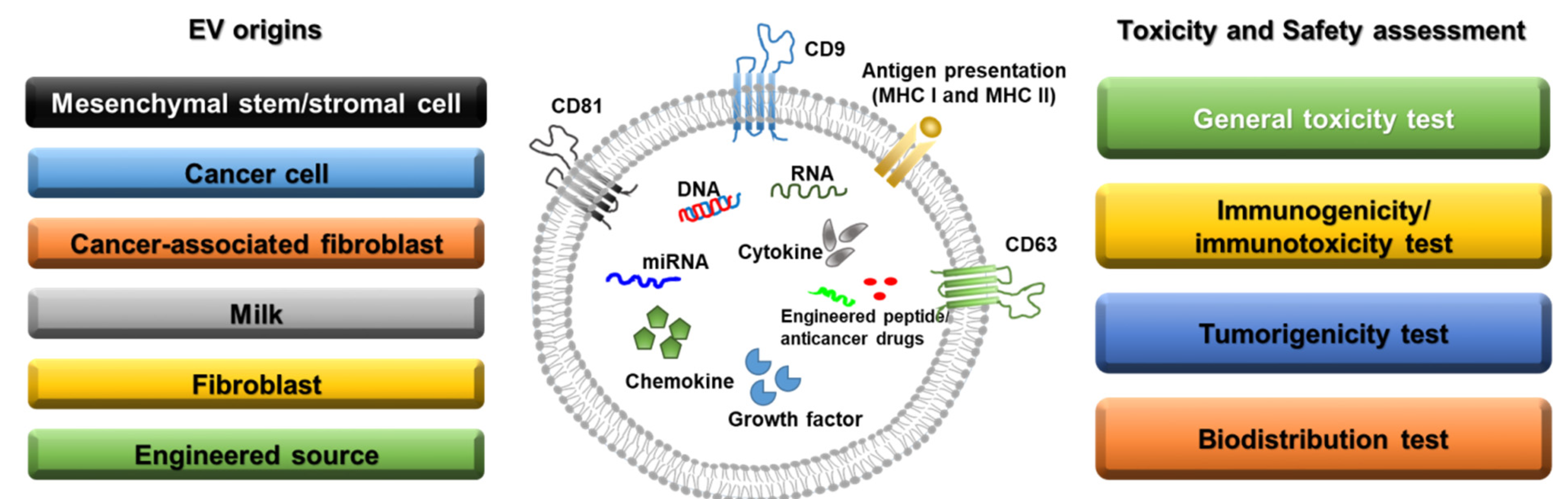

Figure 1. Sources of extracellular vesicles and toxicity/safety assessments. EVs can originate from mesenchymal stem/stromal cells, cancer cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, milk, normal fibroblasts, and engineered cells. EVs have a lipid bilayer and can contain transmembrane proteins, antigen presentation proteins, DNA, RNA, miRNA, cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, engineered peptides, and anticancer drugs. Before clinical studies of EVs, general toxicity, immunogenicity, tumorigenicity, and biodistribution tests should be performed in preclinical studies depending on the source of the EVs.

2. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived EVs

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been widely investigated as therapeutic options for various diseases, including graft versus host disease [18] and cardiac [19], neurological [20], and orthopedic [21] disorders. MSCs mainly reduce inflammation, enhance progenitor cell proliferation, improve tissue repair, and decrease infection. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, over 35,000 clinical trials have been conducted in the USA, France, and Canada on cell-based therapies [22]. However, despite the potency of MSCs, numerous side effects, such as tumorigenesis and immunogenicity, have been reported in preclinical and clinical trials [23]. In addition, there are some limitations to the generation and storage of MSCs intended for use as therapeutics [24]. To maintain the efficacy of MSCs and overcome these drawbacks, MSC-derived EVs have received attention as therapeutic agents that can be used for renal protection and to manage various disorders, including cardiac dysfunction, myocardial infarction, stroke, hepatic fibrosis, and vascular proliferative diseases [25,26,27,28,29,30][25][26][27][28][29][30]. In particular, MSC-derived EVs are composed of factors such as cytokines, growth factors, RNA, and miRNAs, which originate from MSCs and thus exert similar effects to those of MSCs [31]. The effects of MSC-derived EVs in cancer cell biology are controversial [32]. Many groups have reported that MSC-derived EVs increase cancer proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Bone marrow MSC-derived EVs were reported to stimulate the hedgehog signaling pathway in the growth of osteosarcoma and gastric cancer [33], whereas adipocyte MSC-derived EVs promoted breast cancer cell growth via activation of the Hippo signaling pathway [34]. However, adipose MSC-derived EVs inhibited prostate cancer growth by delivering miR-145 [35]. MSC-derived EVs of different origins show different effects in various diseases with divergent mechanisms. Further information is provided in Table 1.Table 1.

MSC-derived EVs of different origins with different effects in various diseases.

| EV Origin | Target Disease | Mechanisms & Characteristics | Animals Used | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Wound healing | Promoting M2 polarization of macrophages miR-223 wound healing by transferring EV-derived microRNA |

6–8 weeks old female C57BL/6 J mice | [28] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Alzheimer’s disease | Evaluating mouse cognitive deficits Stimulating neurogenesis in the subventricular zone Alleviating beta amyloid 1−42-induced cognitive impairment |

7–8-week-old C57BL/6 mice | [36] |

| Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells | Cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury | Protection of animals from death due to cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury | 6-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats | [37] |

| Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus | Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects Increasing normal hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive and memory function |

6–8-week-old C57BL/6 mice | [38] |

| Mesenchymal stromal cells | A newborn rat model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) induced by 14 days of neonatal hyperoxia exposure (85% O2) | Protecting from apoptosis, inhibiting inflammation, and increasing angiogenesis Preventing the disruption of alveolar growth, increasing small blood vessel number, and inhibiting right heart hypertrophy at P14, P21, and P56 |

Newborn rats | [39] |

| Embryonic mesenchymal stem cells | Critical-sized osteochondral defects (1.5 mm diameter and 1.0 mm depth) | Complete restoration of cartilage and subchondral bone | 8-week-old female Sprague Dawley rats | [40] |

| Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells | Perinatal brain injury (hypoxic-ischemic and inflammatory with lipopolysaccharide) | Inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory molecules and preventing microgliosis in rats with perinatal brain injury Decreasing TNF-α and IL-1β expression in injured brains |

2-day-old Wistar rat pups | [41] |

| Umbilical Cord mesenchymal stem cells | CCl4-induced liver injury | Suppressing the development of liver tumors Inhibiting oxidative stress in liver tumors Reducing oxidative stress and inhibiting apoptosis in liver fibrosis |

4–5-week-old female BALB/c mice | [42] |

| Mesenchymal stromal cells | Cavernous nerve injury (CNI) | Enhancing smooth muscle content and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) in the corpus cavernosum Improving erectile function after CNI Increasing penile nNOS expression and alleviating cell apoptosis |

10-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats | [43] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) with a 20 mm cylindrical impactor hemorrhaged over 12.5 min using a Masterflex pump |

Lowering Neurological Severity Score (NSS) (p < 0.05) during the first five days post-injury Faster full neurological recovery |

35–45 kg female Yorkshire swine | [44] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | UV-irradiated skin | Attenuating UV-induced histological injury and inflammatory response in mouse skin Preventing cell proliferation and collagen deposition in UV-irradiated mouse skin Increasing antioxidant activity |

newborn and adult Kunming mice | [45] |

3. Cancer-Derived EVs

EVs from tumor cells can be produced and utilized to stimulate or inhibit tumor growth under various conditions, depending on whether they will or will not be used for cancer treatment. Cancer-derived EVs can be detected in all bodily fluids, such as the blood, saliva, urine, and bile [14,46,47][14][46][47]. Based on this characteristic, many scientists have attempted to develop cancer-derived EVs as noninvasive biomarkers for diagnosing cancer in early stages of disease [48]. Specifically, cancer-derived EVs contain various biomarkers, such as miR-17, miR-19a, miR-21, miR-126/miR-141, miR-146, and miR-409, which have a range of effects on tumor growth and can be used for cancer diagnosis and prognosis [49,50,51,52][49][50][51][52]. The extracellular matrix, cancer-associated fibroblasts, inflammatory immune cells, and tumor-associated vasculature are components of the tumor microenvironment, which can be a major source of tumor-derived EVs [53,54][53][54]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are among the major sources of tumor EVs with different effects before and after chemotherapy [55]. In particular, following chemotherapies, EVs derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts were shown to promote the chemoresistance and proliferation of colorectal and breast cancers [56,57][56][57]. EVs from tumors under hypoxic conditions enhanced angiogenesis and metastasis by modulating the microenvironment [58]. Because tumor-derived EVs contain important components, including nucleic acids and oncogenic proteins, they can be used as biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, therapeutic response prediction, and targeted therapy [4].4. EVs as Anticancer Drug Delivery Agents

Jang et al. reported that EV-delivered doxorubicin had a greater effect on reducing tumor size than administration of pure doxorubicin in a colon adenocarcinoma xenograft model [59]. Furthermore, the use of an αv integrin-specific iRGD peptide with EVs to deliver doxorubicin showed promising anticancer effects in an αv integrin-positive breast cancer model [60]. Following the investigation of paclitaxel using an EV delivery system in a tumor xenograft model, Kim et al. reported its anticancer effects in vitro and in vivo [61]. Another group reported that EV-encapsulated paclitaxel directly targeted cancer stem cells that exhibited anticancer drug resistance [62]. EVs loaded with the antitumor drugs withaferin A or celastrol were administered to a human lung cancer xenograft mouse model, in which they showed anticancer effects [63,64][63][64]. Engineered EVs with superparamagnetic-conjugated transferrin have been shown to target tumor cells and reduce tumor growth in vivo [65]. In addition, an engineered anti-epidermal growth factor receptor nanobody fused with the EV anchor signal peptide glycosylphosphatidylinositol showed direct activity against tumor cells positive for epidermal growth factor receptor-positive tumor cells [66]. Because of their stability in biological fluids, EVs can escape from lung clearance and cross the blood-brain barrier [67,68][67][68], thus easily reaching tumors in various organs such as the liver, brain, and breast. Based on these characteristics, EVs can be used for cancer-targeting therapies.References

- Povero, D.; Eguchi, A.; Li, H.; Johnson, C.D.; Papouchado, B.G.; Wree, A.; Messer, K.; Feldstein, A.E. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous small membrane structures that originate from plasma membranes. Although most EVs have a diameter of 50–200 nm, larger ones are also observed. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113651.

- Vlassov, A.V.; Magdaleno, S.; Setterquist, R.; Conrad, R. Exosomes: Current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 940–948.

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659.

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, L.; Qian, H.; Xu, W. Exosomes in cancer: Small particle, big player. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 8, 83.

- Elliot, S.; Schneider, A.; Simons, M. Exosomes: Vesicular carriers for intercellular communication in neurodegenerative disorders. Cell Tissue Res. 2013, 352, 33–47.

- Alsaif, M.; Elliot, S.A.; MacKenzie, M.L.; Prado, C.M.; Field, C.J.; Haqq, A.M. Energy Metabolism Profile in Individuals with Prader-Willi Syndrome and Implications for Clinical Management: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 905–915.

- Lopez-Verrilli, M.A.; Court, F.A. Exosomes: Mediators of communication in eukaryotes. Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 5–11.

- He, C.; Zheng, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, B. Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine. Theranostics 2018, 8, 237–255.

- Batrakova, E.V.; Kim, M.S. Using exosomes, naturally-equipped nanocarriers, for drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2015, 219, 396–405.

- Harding, C.; Heuser, J.; Stahl, P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1983, 97, 329–339.

- Caby, M.P.; Lankar, D.; Vincendeau-Scherrer, C.; Raposo, G.; Bonnerot, C. Exosomal-like vesicles are present in human blood plasma. Int. Immunol. 2005, 17, 879–887.

- Masyuk, A.I.; Huang, B.Q.; Ward, C.J.; Gradilone, S.A.; Banales, J.M.; Masyuk, T.V.; Radtke, B.; Splinter, P.L.; LaRusso, N.F. Biliary exosomes influence cholangiocyte regulatory mechanisms and proliferation through interaction with primary cilia. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 299, G990–G999.

- Admyre, C.; Johansson, S.M.; Qazi, K.R.; Filén, J.-J.; Lahesmaa, R.; Norman, M.; Neve, E.P.A.; Scheynius, A.; Gabrielsson, S. Exosomes with immune modulatory features are present in human breast milk. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1969–1978.

- Pisitkun, T.; Shen, R.F.; Knepper, M.A. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 13368–13373.

- Welton, J.L.; Loveless, S.; Stone, T.; von Ruhland, C.; Robertson, N.P.; Clayton, A. Cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicle enrichment for protein biomarker discovery in neurological disease; multiple sclerosis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1369805.

- Mirza, A.H.; Kaur, S.; Nielsen, L.B.; Størling, J.; Yarani, R.; Roursgaard, M.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Damm, P.; Svare, J.; Mortensen, H.B.; et al. Breast Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Enriched in Exosomes From Mothers With Type 1 Diabetes Contain Aberrant Levels of microRNAs. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2543.

- Halvaei, S.; Daryani, S.; Eslami, S.Z.; Samadi, T.; Jafarbeik-Iravani, N.; Bakhshayesh, T.O.; Majidzadeh, A.K.; Esmaeili, R. Exosomes in Cancer Liquid Biopsy: A Focus on Breast Cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 10, 131–141.

- Amorin, B.; Alegretti, A.P.; Valim, V.; Pezzi, A.; Laureano, A.M.; Lima da Silva, M.A.; Wieck, A.; Silla, L. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy and acute graft-versus-host disease: A review. Hum. Cell. 2014, 27, 137–150.

- Bagno, L.; Hatzistergos, K.E.; Balkan, W.; Hare, J.M. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease: Progress and Challenges. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 1610–1623.

- Mukai, T.; Tojo, A.; Nagamura-Inoue, T. Mesenchymal stromal cells as a potential therapeutic for neurological disorders. Regen. Ther. 2018, 9, 32–37.

- Fernandes, T.L.; Kimura, H.A.; Gomes Pinheiro, C.C.; Shimomura, K.; Nakamura, N.; Ferreira, J.R.; Gomoll, A.H.; Hernandez, A.J.; Franco Bueno, D. Human Synovial Mesenchymal Stem Cells Good Manufacturing Practices for Articular Cartilage Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2018, 24, 709–716.

- Golchin, A.; Farahany, T.Z. Biological Products: Cellular Therapy and FDA Approved Products. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2019, 15, 166–175.

- Lukomska, B.; Stanaszek, L.; Zuba-Surma, E.; Legosz, P.; Sarzynska, S.; Drela, K. Challenges and Controversies in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 9628536.

- Shin, T.H.; Lee, S.; Choi, K.R.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, Y.; Paik, M.J.; Seo, C.; Kang, S.; Jin, M.S.; Yoo, T.H.; et al. Quality and freshness of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells decrease over time after trypsinization and storage in phosphate-buffered saline. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1106.

- Chai, H.T.; Sheu, J.-J.; Chiang, J.Y.; Shao, P.-L.; Wu, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-L.; Li, Y.-C.; Sung, P.-H.; Lee, F.-Y.; Yip, H.-K. Early administration of cold water and adipose derived mesenchymal stem cell derived exosome effectively protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 5375–5389.

- Zhu, B.; Zhang, L.; Liang, C.; Liu, B.; Pan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, W.; Yan, B.; et al. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Prevent Aging-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction through a Novel Exosome/lncRNA MALAT1/NF-kappaB/TNF-alpha Signaling Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 9739258.

- Yan, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C.; Liu, B.; Ding, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, R.; Yu, X.-Y.; Li, Y. Stem cell-derived exosomes prevent pyroptosis and repair ischemic muscle injury through a novel exosome/circHIPK3/ FOXO3a pathway. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6728–6742.

- He, X.; Dong, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Liao, L.; Jin, Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, B. MSC-Derived Exosome Promotes M2 Polarization and Enhances Cutaneous Wound Healing. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 7132708.

- Li, T.; Yan, Y.; Wang, B.; Qian, H.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, W.; Li, W.; et al. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate liver fibrosis. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 845–854.

- Shabbir, A.; Cox, A.; Rodriguez-Menocal, L.; Salgado, M.; Van Badiavas, E. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes Induce Proliferation and Migration of Normal and Chronic Wound Fibroblasts, and Enhance Angiogenesis In Vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 2015, 24, 1635–1647.

- Park, K.S.; Bandeira, E.; Shelke, G.V.; Lässer, C.; Lötvall, J. Enhancement of therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 288.

- Vakhshiteh, F.; Atyabi, F.; Ostad, S.N. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes: A two-edged sword in cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 2847–2859.

- Qi, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, L.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y. Exosomes Derived from Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Tumor Growth Through Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 2242–2254.

- Wang, S.; Su, X.; Xu, M.; Xiao, X.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Keating, A.; Zhao, R.C. Exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-derived adipocytes promote breast cancer cell growth via activation of Hippo signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 117.

- Che, Y.; Shi, X.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ai, Q.; Shi, Y.; Gong, F.; Jiang, W. Exosomes Derived from miR-143-Overexpressing MSCs Inhibit Cell Migration and Invasion in Human Prostate Cancer by Downregulating TFF3. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 18, 232–244.

- Reza-Zaldivar, E.E.; Hernández-Sapiéns, M.A.; Gutiérrez-Mercado, Y.K.; Sandoval-Ávila, S.; Gomez-Pinedo, U.; Márquez-Aguirre, A.L.; Vázquez-Méndez, E.; Padilla-Camberos, E.; Canales-Aguirre, A.A. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote neurogenesis and cognitive function recovery in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1626–1634.

- Lee, J.H.; Ha, D.H.; Go, H.K.; Youn, J.; Kim, H.K.; Jin, R.C.; Miller, R.B.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, B.S.; Yi, Y.W. Reproducible Large-Scale Isolation of Exosomes from Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells and Their Application in Acute Kidney Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4774.

- Long, Q.; Upadhya, D.; Hattiangady, B.; Kim, D.K.; An, S.Y.; Shuai, B.; Prockop, D.J.; Shetty, A.K. Intranasal MSC-derived A1-exosomes ease inflammation, and prevent abnormal neurogenesis and memory dysfunction after status epilepticus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3536–E3545.

- Braun, R.K.; Chetty, C.; Balasubramaniam, V.; Centanni, R.; Haraldsdottir, K.; Hematti, P.; Eldridge, M.W. Intraperitoneal injection of MSC-derived exosomes prevent experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 2653–2658.

- Zhang, S.; Chu, W.C.; Lai, R.C.; Lim, S.K.; Hui, J.H.; Toh, W.S. Exosomes derived from human embryonic mesenchymal stem cells promote osteochondral regeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016, 24, 2135–2140.

- Thomi, G.; Surbek, D.; Haesler, V.; Joerger-Messerli, M.; Schoeberlein, A. Exosomes derived from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells reduce microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in perinatal brain injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 105.

- Jiang, W.; Tan, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhao, T.; Mao, F.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Yan, Z.; Qian, H.; Yan, Y. Human Umbilical Cord MSC-Derived Exosomes Suppress the Development of CCl4-Induced Liver Injury through Antioxidant Effect. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 6079642.

- Ouyang, X.; Han, X.; Chen, Z.; Fang, J.; Huang, X.; Wei, H. MSC-derived exosomes ameliorate erectile dysfunction by alleviation of corpus cavernosum smooth muscle apoptosis in a rat model of cavernous nerve injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 246.

- Williams, A.M.; Dennahy, I.S.; Bhatti, U.F.; Halaweish, I.; Xiong, Y.; Chang, P.; Nikolian, V.C.; Chtraklin, K.; Brown, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Provide Neuroprotection and Improve Long-Term Neurologic Outcomes in a Swine Model of Traumatic Brain Injury and Hemorrhagic Shock. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 54–60.

- Wang, T.; Jian, Z.; Baskys, A.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Guo, H.; Hei, Y.; Xian, P.; He, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. MSC-derived exosomes protect against oxidative stress-induced skin injury via adaptive regulation of the NRF2 defense system. Biomaterials 2020, 257, 120264.

- Han, Y.; Jia, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, W. Salivary Exosomes: Emerging Roles in Systemic Disease. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 633–643.

- Lasser, C.; Alikhani, V.S.; Ekström, K.; Eldh, M.; Torregrosa Paredes, P.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Gabrielsson, S.; Lötvall, J.; Valadi, H. Human saliva, plasma and breast milk exosomes contain RNA: Uptake by macrophages. J. Transl. Med. 2011, 9, 9.

- Nonaka, T.; Wong, D.T.W. Saliva-Exosomics in Cancer: Molecular Characterization of Cancer-Derived Exosomes in Saliva. Enzymes 2017, 42, 125–151.

- Pfeffer, S.R.; Grossmann, K.F.; Cassidy, P.B.; Yang, C.H.; Fan, M.; Kopelovich, L.; Leachman, S.A.; Pfeffer, L.M. Detection of Exosomal miRNAs in the Plasma of Melanoma Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 2012–2027.

- Li, Z.; Ma, Y.Y.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.F.; Li, R.; Kang, W.; Hao, X.K. Exosomal microRNA-141 is upregulated in the serum of prostate cancer patients. Onco. Targets Ther. 2016, 9, 139–148.

- Lee, J.C.; Zhao, J.T.; Gundara, J.; Serpell, J.; Bach, L.A.; Sidhu, S. Papillary thyroid cancer-derived exosomes contain miRNA-146b and miRNA-222. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 196, 39–48.

- Grimolizzi, F.; Monaco, F.; Leoni, F.; Bracci, M.; Staffolani, S.; Bersaglieri, C.; Gaetani, S.; Valentino, M.; Amati, M.; Rubini, C.; et al. Exosomal miR-126 as a circulating biomarker in non-small-cell lung cancer regulating cancer progression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15277.

- Luga, V.; Zhang, L.; Viloria-Petit, A.M.; Ogunjimi, A.A.; Inanlou, M.R.; Chiu, E.; Buchanan, M.; Hosein, A.N.; Basik, M.; Wrana, J.L. Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell 2012, 151, 1542–1556.

- Hu, C.; Chen, M.; Jiang, R.; Guo, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, X. Exosome-related tumor microenvironment. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 3084–3092.

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Zou, L.; Zhu, Z. Role of Exosomes in Crosstalk Between Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 356.

- Richards, K.E.; Zeleniak, A.E.; Fishel, M.L.; Wu, J.; Littlepage, L.E.; Hill, R. Cancer-associated fibroblast exosomes regulate survival and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1770–1778.

- Fiori, M.E.; Di Franco, S.; Villanova, L.; Bianca, P.; Stassi, G.; De Maria, R. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as abettors of tumor progression at the crossroads of EMT and therapy resistance. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 70.

- Meng, W.; Hao, Y.; He, C.; Li, L.; Zhu, G. Exosome-orchestrated hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 57.

- Jang, S.C.; Kim, O.Y.; Yoon, C.M.; Choi, D.S.; Roh, T.Y.; Park, J.; Nilsson, J.; Lötvall, J.; Kim, Y.K.; Gho, Y.S. Bioinspired exosome-mimetic nanovesicles for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics to malignant tumors. ACS Nano. 2013, 7, 7698–7710.

- Tian, Y.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Ji, T.; Zhu, M.; Anderson, G.J.; Wei, J.; Nie, G. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2383–2390.

- Kim, M.S.; Haney, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; Mahajan, V.; Deygen, I.; Klyachko, N.L.; Inskoe, E.; Piroyan, A.; Sokolsky, M.; Okolie, O.; et al. Development of exosome-encapsulated paclitaxel to overcome MDR in cancer cells. Nanomedicine 2016, 12, 655–664.

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, M. Exosome-Based Cancer Therapy: Implication for Targeting Cancer Stem Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 533.

- Munagala, R.; Aqil, F.; Jeyabalan, J.; Agrawal, A.K.; Mudd, A.M.; Kyakulaga, A.H.; Singh, I.P.; Vadhanam, M.V.; Gupta, R.C. Exosomal formulation of anthocyanidins against multiple cancer types. Cancer Lett. 2017, 393, 94–102.

- Aqil, F.; Kausar, H.; Agrawal, A.K.; Jeyabalan, J.; Kyakulaga, A.H.; Munagala, R.; Gupta, R. Exosomal formulation enhances therapeutic response of celastrol against lung cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2016, 101, 12–21.

- Qi, H.; Liu, C.; Long, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chang, X.; Qian, X.; Jia, H.; Zhao, J.; Sun, J.; et al. Blood Exosomes Endowed with Magnetic and Targeting Properties for Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano. 2016, 10, 3323–3333.

- Kooijmans, S.A.; Aleza, C.G.; Roffler, S.R.; van Solinge, W.W.; Vader, P.; Schiffelers, R.M. Display of GPI-anchored anti-EGFR nanobodies on extracellular vesicles promotes tumour cell targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2016, 5, 31053.

- Kawikova, I.; Askenase, P.W. Diagnostic and therapeutic potentials of exosomes in CNS diseases. Brain Res. 2015, 1617, 63–71.

- Moyano, A.L.; Li, G.; Boullerne, A.I.; Feinstein, D.L.; Hartman, E.; Skias, D.; Balavanov, R.; van Breemen, R.B.; Bongarzone, E.R.; Månsson, J.E.; et al. Sulfatides in extracellular vesicles isolated from plasma of multiple sclerosis patients. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 94, 1579–1587.

More