Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Min Heui Yoo and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous small membrane structures that originate from plasma membranes. Although most EVs have a diameter of 50–200 nm, larger ones are also observed. Generally, particles up to a diameter of 1000 nm are regarded as EVs. They are typically isolated from the conditioned media of cultured cells. The contents of EVs include proteins, mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), and nucleic acids. Each vesicle performs a specific function in transferring biological material(s) to induce biological processes, such as replication, growth, apoptosis, and necrosis.

- Extracellular vesicles

1. Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous small membrane structures that originate from plasma membranes. Although most EVs have a diameter of 50–200 nm, larger ones are also observed. Generally, particles up to a diameter of 1000 nm are regarded as EVs [1][2][1,2]. They are typically isolated from the conditioned media of cultured cells. The contents of EVs include proteins, mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), and nucleic acids [3]. Each vesicle performs a specific function in transferring biological material(s) to induce biological processes, such as replication, growth, apoptosis, and necrosis [4][5][6][4,5,6]. They are also required for cell-to-cell communication to maintain a normal homeostatic state [7]. EVs can be used as cargo carriers in physiological or pathological conditions and are considered biomarkers representing altered normal physiological states [8]. Based on these characteristics, EVs can be used for diverse purposes, from cosmetic to therapeutic applications. The main advantage of EVs is their limited adverse effects when used for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes, because they are composed of cell-derived materials and because of their potential for targeted cell delivery [9]. In addition, compared to cells, they are easier to store and transport.

The first EV that was identified is involved in transferrin receptor elimination, which plays a role in the maturation of reticulocytes, as reported by Harding et al. in 1983 [10]. The authors demonstrated the release of multi-vascular endosomes from the plasma membrane by exocytosis in rat reticulocytes. EVs can be found in all types of body fluids, such as plasma [11], bile [12], breast milk [13], urine [14], ascites, and cerebrospinal fluid [15]. Thus, these vesicles show potential for revealing abnormal conditions in various organs. EVs from the blood can be used to detect inflammation or an aberrant immune system, whereas those from breast milk can be utilized to diagnose breast conditions [16]. Halvaei et al. reported that EVs can be used for the diagnosis of various cancers using cancer-specific miRNAs [17].

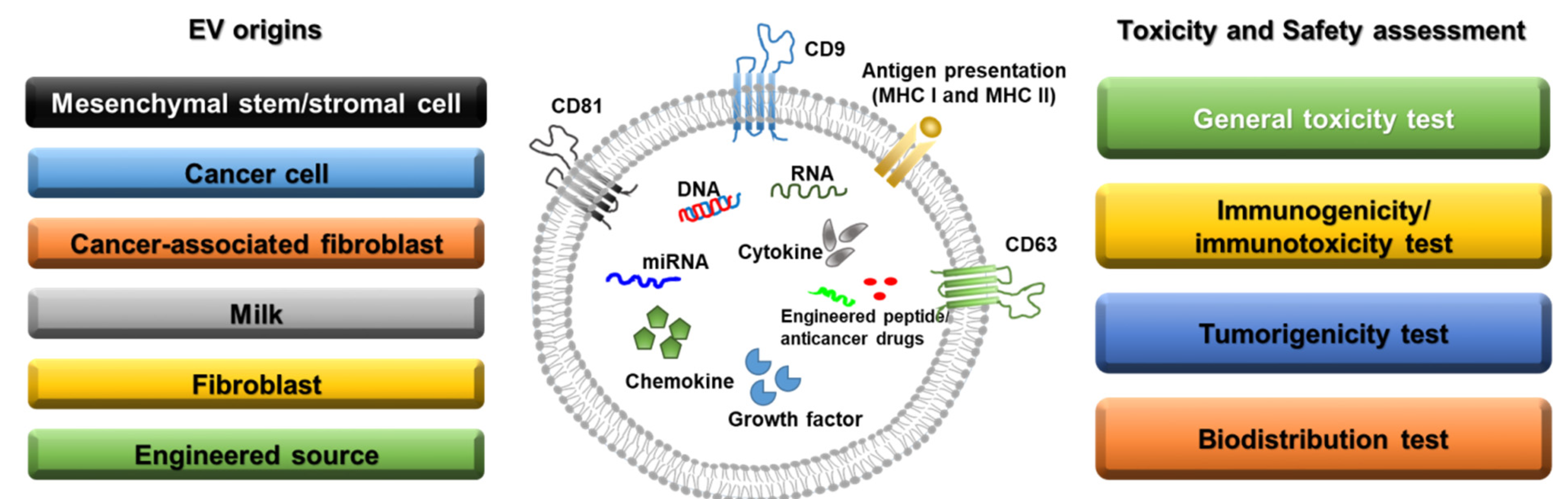

Figure 1. Sources of extracellular vesicles and toxicity/safety assessments. EVs can originate from mesenchymal stem/stromal cells, cancer cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, milk, normal fibroblasts, and engineered cells. EVs have a lipid bilayer and can contain transmembrane proteins, antigen presentation proteins, DNA, RNA, miRNA, cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, engineered peptides, and anticancer drugs. Before clinical studies of EVs, general toxicity, immunogenicity, tumorigenicity, and biodistribution tests should be performed in preclinical studies depending on the source of the EVs.

2. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived EVs

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been widely investigated as therapeutic options for various diseases, including graft versus host disease [18] and cardiac [19], neurological [20], and orthopedic [21] disorders. MSCs mainly reduce inflammation, enhance progenitor cell proliferation, improve tissue repair, and decrease infection. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, over 35,000 clinical trials have been conducted in the USA, France, and Canada on cell-based therapies [22]. However, despite the potency of MSCs, numerous side effects, such as tumorigenesis and immunogenicity, have been reported in preclinical and clinical trials [23]. In addition, there are some limitations to the generation and storage of MSCs intended for use as therapeutics [24]. To maintain the efficacy of MSCs and overcome these drawbacks, MSC-derived EVs have received attention as therapeutic agents that can be used for renal protection and to manage various disorders, including cardiac dysfunction, myocardial infarction, stroke, hepatic fibrosis, and vascular proliferative diseases [25][26][27][28][29][30][25,26,27,28,29,30]. In particular, MSC-derived EVs are composed of factors such as cytokines, growth factors, RNA, and miRNAs, which originate from MSCs and thus exert similar effects to those of MSCs [31]. The effects of MSC-derived EVs in cancer cell biology are controversial [32]. Many groups have reported that MSC-derived EVs increase cancer proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Bone marrow MSC-derived EVs were reported to stimulate the hedgehog signaling pathway in the growth of osteosarcoma and gastric cancer [33], whereas adipocyte MSC-derived EVs promoted breast cancer cell growth via activation of the Hippo signaling pathway [34]. However, adipose MSC-derived EVs inhibited prostate cancer growth by delivering miR-145 [35]. MSC-derived EVs of different origins show different effects in various diseases with divergent mechanisms. Further information is provided in Table 1.Table 1.

MSC-derived EVs of different origins with different effects in various diseases.

| EV Origin | Target Disease | Mechanisms & Characteristics | Animals Used | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Wound healing | Promoting M2 polarization of macrophages miR-223 wound healing by transferring EV-derived microRNA |

6–8 weeks old female C57BL/6 J mice | [28] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Alzheimer’s disease | Evaluating mouse cognitive deficits Stimulating neurogenesis in the subventricular zone Alleviating beta amyloid 1−42-induced cognitive impairment |

7–8-week-old C57BL/6 mice | [36] |

| Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells | Cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury | Protection of animals from death due to cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury | 6-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats | [37] |

| Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus | Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects Increasing normal hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive and memory function |

6–8-week-old C57BL/6 mice | [38] |

| Mesenchymal stromal cells | A newborn rat model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) induced by 14 days of neonatal hyperoxia exposure (85% O2) | Protecting from apoptosis, inhibiting inflammation, and increasing angiogenesis Preventing the disruption of alveolar growth, increasing small blood vessel number, and inhibiting right heart hypertrophy at P14, P21, and P56 |

Newborn rats | [39] |

| Embryonic mesenchymal stem cells | Critical-sized osteochondral defects (1.5 mm diameter and 1.0 mm depth) | Complete restoration of cartilage and subchondral bone | 8-week-old female Sprague Dawley rats | [40] |

| Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells | Perinatal brain injury (hypoxic-ischemic and inflammatory with lipopolysaccharide) | Inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory molecules and preventing microgliosis in rats with perinatal brain injury Decreasing TNF-α and IL-1β expression in injured brains |

2-day-old Wistar rat pups | [41] |

| Umbilical Cord mesenchymal stem cells | CCl4-induced liver injury | Suppressing the development of liver tumors Inhibiting oxidative stress in liver tumors Reducing oxidative stress and inhibiting apoptosis in liver fibrosis |

4–5-week-old female BALB/c mice | [42] |

| Mesenchymal stromal cells | Cavernous nerve injury (CNI) | Enhancing smooth muscle content and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) in the corpus cavernosum Improving erectile function after CNI Increasing penile nNOS expression and alleviating cell apoptosis |

10-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats | [43] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) with a 20 mm cylindrical impactor hemorrhaged over 12.5 min using a Masterflex pump |

Lowering Neurological Severity Score (NSS) (p < 0.05) during the first five days post-injury Faster full neurological recovery |

35–45 kg female Yorkshire swine | [44] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | UV-irradiated skin | Attenuating UV-induced histological injury and inflammatory response in mouse skin Preventing cell proliferation and collagen deposition in UV-irradiated mouse skin Increasing antioxidant activity |

newborn and adult Kunming mice | [45] |