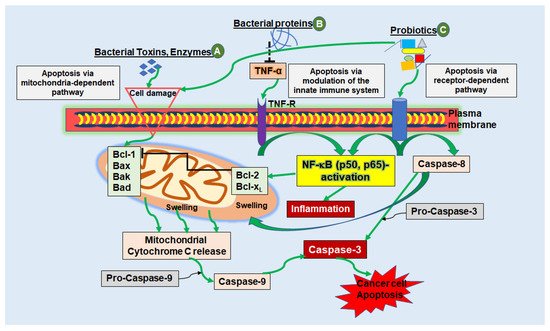

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing the mechanisms of apoptosis triggered by bacterial peptides in cancer cells. (

A) Bacterial toxins, secreted by various bacterial strains can cause apoptosis via the mitochondria-dependent pathway by causing cell injury, for example, by cell membrane pore formation. Induction of the intrinsic pathway leads to activation of pro-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-1, Bad, Bax, Bak), which in turn stimulates the release of cytochrome c molecules from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol. Cytochrome c, together with Caspase-9 forms a complex called the “apoptosome”, finally stimulating executioner caspases (e.g., Caspase-3) leading to cancer cell apoptosis. (

B) Bacterial proteins and peptides can have a modulatory impact on cytokines such as TNF-α, resulting in activation or blockage of NF-κB. With suppression of NF-κB, which stimulates anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, which in turn regulates apoptosis by blocking cytochrome c release, pro-apoptotic Bax and Bak-proteins remain stimulated and apoptosis is induced. (

C) Besides stimulating the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis, probiotics are capable of apoptosis induction through stimulation of the extrinsic receptor-dependent pathway. Here, so called cell death receptors, such as TNF-R, bind to natural ligands, whereby initiator Caspase-8 and -10 are activated to cleave further downstream caspases, such as Caspase-3, which in turn induces cell apoptosis

[41,42,43,44,45][41][42][43][44][45].

Altogether, to make use of these mechanisms such as bacteria-induced apoptosis and metastasis suppression and to establish efficient therapy methods within using bacteria, it is important to meet several framework conditions such as maximum cytotoxicity against cancer cells with minimum cytotoxicity towards intact cell tissue and the ability to selectively attack carcinomas

[20,40][20][40].

3. Microbiota in CRC

3.1. Influence of Microbiota on Drug Metabolism

With a bacteria-to-cell ratio of roughly 1:1 in the human body, microbes encode for 150 times more genes than the human genome

[19]. The discovery of microbiota-specific metabolic signatures contributes to a better knowledge of the relation between bacteria and human cells and several studies have demonstrated that microbiota-dependent metabolites have a great impact on the immune function, therefore better understanding could aid in the prediction of drug effects and outcomes in their application.

Han and colleagues used a library of 833 metabolites to describe the metabolic identities of 178 gut bacteria with mass spectrometry and a machine learning workflow by using murine serum, urine, feces and caecal contents

[136,137][46][47]. In this study, they could precisely map genes according to bacteria’s metabolism and their phenotypic variation as well as associate metabolites with microbial strains. For example,

Firmicutes and

Actinobacteria, which are two phylogenetically distant strains were found to produce high levels of ornithine, which is important for the regulation of several metabolic processes, whereas

Enterococcus faecalis and

Enterococcus faecium were demonstrated to accumulate high levels of tyramine that is known to modulate neurological functions. On the other hand,

C. cadaveris has been shown to act as a consumer instead of a producer and to consume high levels of vitamin B5 that is linked to inflammatory bowel diseases

[136,138,139][46][48][49].

These observations highlight the great potential of better knowledge about microbiota-dependent metabolites in drug therapy, because orally delivered chemicals are mainly absorbed in the gut and therefore represents the site where the majority of metabolic changes of medication takes place

[137][47].

Because medications have a significant impact on microbiota composition and balance, it is critical to bring up the interacting relationship between drug components and the microbiome

[140][50]. Anti-diabetics, proton pump inhibitors

[140][50] and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are all representations of drug-induced toxicity on microorganisms

[33]. However, bacteria have also been discovered to have the ability to digest medicines. In a previous study, Maier et al. applied 1197 medicines from various therapeutic classes to 40 distinct bacteria species, excluding antibiotics, in an attempt to widely and thoroughly address these effects

[140][50]. The researchers found that almost 30% of the substances examined hindered the proliferation of at least one bacterial species, therefore they hypothesized that antibiotic resistance may also arise as a result of changes in the microbiota caused by non-antibiotic exposure

[140][50]. Genetic screens, and enzymatic analysis to find enzymes promoting specific drug conversions, have been used to investigate the reasons and effects of drug-microbiota interactions

[141][51]. Recently, the metabolism of gut microbiota has gained more attention since it may explain why individuals suffering from the same disease and undergo the same treatment, show different therapeutical outcomes. Moreover, it shows the complex and challenging task to find an efficient treatment strategy for every individual. In order to find appropriate drugs for every patient, machine-learning frameworks using network-based analyses and data to identify drug biomarkers predicting drug responses increasingly take place

[142][52]. With machine learning models and artificial intelligence, individual-specific cancer therapy can be developed to help improve therapeutic outcomes

[142,143][52][53]. Furthermore, identifying hazardous by-products of bacterial medication aids in the prediction of potential adverse effects in patients undergoing therapy. With the wide spectrum of impacts of bacteria-induced chemical metabolism, such as pharmacological activation

[144][54], inactivation

[145][55] or toxicity

[141][51], pinpointing the bacteria or their characteristics causing a specific metabolic effect is currently one of the most challenging aspects of treatments. For example by influencing the TNF response or ROS production

[146][56], metabolic processes of glucuronidation conjugating pharmaceuticals to glucuronic acid (GlcA) in the liver, inactivates and detoxifies medicines. These glucuronides are then taken to the gut and are eliminated from the body

[147][57]. However, once in the colon, these compounds can be reactivated by gut bacterialglucuronidases (GUS) enzymes by removing the GlcA, resulting in local acute toxicity

[148][58]. Furthermore, as customized medicine is becoming increasingly important, research is currently being conducted into the extent to which individual drug metabolism can be harnessed. Javdan et al. created a technique to find metabolites formed by microbiome-derived metabolism (MDM) enzymes in a series of 23 orally applied medicines in human healthy donors in order to describe metabolic interactions between microbiota and therapeutical agents

[149][59]. This study included different methodologies, including microbial community cultures, small-molecule structural assay, quantitative metabolomics, metagenomics, mouse colonization and bioinformatic analysis, making it a very extensive and technically heavy approach. The authors demonstrated the efficacy of this technique in identifying MDM enzymes in a high throughput manner utilizing medicines from several groups with varying mechanisms of action

[149][59]. Zimmermann et al. used a related attempt to assess the in vitro ability of 76 naturally occurring bacteria in the human gut to metabolize 271 orally administered pharmaceuticals from various groups based on their mode of action. Surprisingly, at least one of the microbes studied was shown to metabolize up to two-thirds of the medications tested

[150][60]. Furthermore, a single microbe had the ability to digest up to 95 distinct medicines and they were able to discover distinct drug-metabolizing gene products that are accounting for the conversion of medicines into metabolites using metabolomics, mass spectrometry and DNA sequence analysis

[150][60]. Finally, in silico techniques have been created to enable the characterization of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites by certain bacterium species

[140][50] as well as the prediction of toxicity events using data on bacteria composition, drug activity and food preferences

[151][61]. When it comes to medication metabolism in the human body, more evidence has pointing out the importance of gut microbiota, as bacteria and their metabolites can affect pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, which is a significant finding in context to therapy.

3.2. Influence of Microbiota on Conventional CRC Therapy

In conventional CRC therapy, chemotherapeutic agents and radiation are used and, due to their insufficiency, co-treatment with supplements, phytopharmaceuticals or feces transplantation, with its influence on the microbiome, are becoming increasingly interesting. Chemotherapeutics have been utilized for decades to treat a variety of human tumors and still represent typical first-line treatment for CRC

[152][62], but are also used in combination with fluoropyrimidine-based substances and oxaliplatin as well as irinotecan

[153][63] at the advanced, non-resectable CRC stage. Nonetheless, a substantial number of patients are likely to experience treatment-related morbidity and mortality due to these medications

[152][62]. Given that CRC develops in close neighborhood to gut bacteria, new research has focused on how the gut microbiota influences the efficacy and toxicity of existing chemotherapeutic treatments

[146][56]. Traditional CRC medicines such as irinotecan, 5-FU and cyclophosphamide have been demonstrated to alter the microbiome diversity of mice in pre-clinical models as well as in human patients. However, it is still unclear how this affects the prognosis, as some research revealed conflicting results when it comes to the role of microbiota in therapy. For example, in an animal experiment, germ-free mice were much more resistant

[154][64] to powerful anti-cancer agent irinotecan

[155][65] and had a higher lethal dose than holoxenic mice

[154][64]. This could be due to the development of metabolites that are harmful to drugs as a consequence of bacterial metabolism. The authors have not thoroughly investigated the ultimate cause of death of these mice and did not identify the crucial bacterial species that accounted for this phenomenon. However, interestingly, irinotecan’s major side effect of diarrhea correlating with intestinal damage was very rarely observed in germ-free mice compared to holoxenic animals

[154][64], while irinotecan-treated patients often show severe diarrhea as a side effect. In their liver, irinotecan is converted to its active form, human topoisomerase I poison SN-38, and then inhibited by DP-glucuronosyltransferases by adding GlcA (SN-38-G)

[156][66]. This inactive compound is revived by GUS in the colon, resulting in acute poisoning. Jariwala et al. discovered the GUS enzymes responsible for SN-38 reactivation in the human gut using a combination of proteomics and bioinformatic analysis on human feces samples under the consideration that SN-38 is a harmful metabolite of irinotecan

[148][58]. Meanwhile, it is known that removing GlcA from SN38-G causes SN38 reactivation, leading to the described disadvantages for the patients. Inhibition of the GUS enzyme synthesis thereby minimizes intestinal damage and maintains irinotecan’s anti-cancer activity

[156][66]. These findings imply that the presence of some bacteria is responsible for an increase in treatment-associated adverse effects leading to the assumption that gut microbiome can influence therapeutic efficacy. Surprisingly, bacteria appear to have a dual function in cancer treatment, with studies reporting a synergistic impact of microbiota and therapeutic efficacy, while some others demonstrate the presence of bacteria as an barrier for the efficacy of drug

[153][63]. With regard to diseases of the digestive organs, research is constantly being conducted into the potential effects of nutritional supplements. More than a decade ago, it was shown that supplementing a high-inulin or oligofructose diet inhibited the growth of a transplantable tumor in a mouse model. Inulin and oligofructose are fructans that have been found to increase Bifidobacteria proliferation in the stomach. The inclusion of these supplements to the animals’ food increased the efficacy of six different chemotherapy medicines, namely 5-FU, doxorubicine, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate as well as cytarabine, implying a prebiotic impact of inulin and oligofructose

[157][67]. An auspicious approach is offered by phytopharmaceuticals, safe secondary plant compounds with numerous health-promoting effects ranging from anti-inflammation to tumor containment. The treatment of CRC cells with resveratrol

[7,158,159][7][68][69] or the components of

Curcuma longa (turmeric) curcumin

[160][70] and calebin A

[13,161,162,163][13][71][72][73] is particularly promising, as these substances can extensively modulate tumor processes. In in vivo-like models, it was shown that all of the three phytopharmaceuticals mentioned above enhance the effect of the cytostatic drug 5-FU

[163][73], and since they alter not only the CRC cells but also the immediate environment as part of their anti-tumor effect, it is obvious that they can also have an influence on the intestinal microbiome.

Another interesting approach is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), firstly introduced in 1958 for treatment of

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI)

[164][74]. Here, up to 80% of all CDI cases could be treated by assisting in the restoration of a beneficial microbiome in infected patients. In addition, FMT was found to be successful in a variety of other illnesses, including inflammatory bowel diseases, diabetes or even autism, thus it became a viable therapy option

[165][75]. The benefits of this method were also addressed as a way to mitigate undesirable effects from radiation treatment due to its safety. For CRC treatment, radiation is utilized as a standard therapeutic strategy in conjunction with chemotherapy

[6], where patients may have a variety of severe adverse effects, such as bone marrow and gastrointestinal damage, thus bacteria have been shown to reduce these adverse effects of radiation treatment in pre-clinical trials and, furthermore, in various pre-clinical cancer mouse models, the gut microbiota has been found to influence even the efficacy of radiation

[166,167][76][77]. Furthermore, worth mentioning, it was shown that applying certain bacteria such as

Lactobacillus rhamnosus to mice undergoing radiotherapy had a protective impact on the intestinal mucosa of the tested animals

[168][78]. Moreover, probiotics were found to reduce radiation-induced gastrointestinal damage in cancer patients undergoing irradiation in clinical investigations such as diarrhea

[150][60].

The future of cancer therapy will undoubtedly lie in the investigation of the dual function of microbiotica in medication outcomes: on the one hand, though bacteria is able to exacerbate therapy side effects as a result of their metabolism, on the other hand the existence of microorganisms is critical for the efficacy of cancer therapeutical agents

[63,166][76][79], playing a special role in CRC and its treatment because of the bacteria-rich digestive organs.