Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Maria Meringolo.

Neurotransmitters play a critical role in developing both the peripheral and the central nervous systems. It is therefore conceivable that neurotransmitter dysfunctions may be involved in ASD pathophysiology. Among neurotransmitters, glutamate (Glu) is considered a good candidate as it is directly involved in brain development and synaptogenesis, memory, behavior, and motor activity regulation, and gastrointestinal functions.

- glutamate receptors

- brain development

1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a mosaic of neurodevelopmental conditions, which show common deficits in two behavioral domains: (i) social interaction and communication difficulties, (ii) narrow interests, and repetitive and stereotyped behaviors (DSM-5) [1,2][1][2]. ASD can be associated with several co-occurring conditions, including seizures, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and other cognitive impairments [3,4][3][4]. The estimated prevalence of ASD is about 1% of the human population [5], with males affected four times more frequently than females [6].

Although it has become clear that ASD has a complex and multifactorial etiopathogenesis, twin and family studies indicate a strong genetic background and high heritability, with a concordance rate of 60% to 95% between monozygotic twins versus 0% to 30% between dizygotic twins [7]. Despite the high heterogeneity between ASD cases, the occurrence of shared symptoms suggests common deficits in some neurodevelopmental pathways. Neurotransmitters play a critical role in developing both the peripheral and the central nervous systems. It is therefore conceivable that neurotransmitter dysfunctions may be involved in ASD pathophysiology. Among neurotransmitters, glutamate (Glu) is considered a good candidate [8,9,10][8][9][10] as it is directly involved in brain development and synaptogenesis [11[11][12],12], memory, behavior, and motor activity regulation [13[13][14][15],14,15], and gastrointestinal functions [16,17][16][17]. Studies on postmortem or body fluids samples provide important evidence about critical changes in Glu concentration in both pediatric and adult patients with ASD [18,19][18][19]. Furthermore, abnormalities in Glu receptors genes and deregulation of glutamatergic pathways have been reported both in ASD patients and animal models [20,21,22,23][20][21][22][23]. In general, excitotoxicity has already been connected with ASD. In addition, the increased prevalence of epilepsy in autistic patients compared to the general population [24,25,26][24][25][26] further strengthens the hypothesis of the dysfunction in excitatory and/or inhibitory network activity. In the past decades, two opposite theories about the role of Glu signaling in ASD have been proposed. In 1998, Carlsson suggested that ASD might result from a decrease in Glu signaling according to (i) overlapping between the ASD condition and the symptoms produced by Glu antagonist, (ii) the neuroanatomical and neuroimaging evidence of glutamatergic areas impairment in ASD patients, (iii) the similarities with ASD symptoms in hypoglutamatergic animals treated with NMDA antagonists [27]. Conversely, Fatemi proposed an opposite theory, suggesting an hyperglutamatergic state in ASD, based on the observation of increased Glu levels in blood samples [19].

2. The Critical Role of the Glutamatergic System in Brain Development

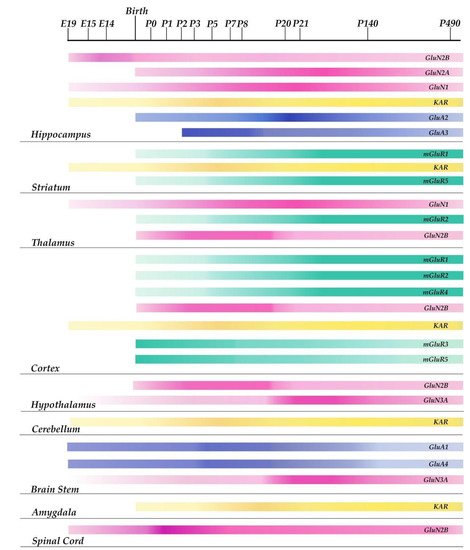

ASD symptoms appear early in development, within the first three years of life, during the fundamental period of rapid synapse formation and maturation [28,29][28][29]. Brain development involves a number of processes, including synaptogenesis, axonal and dendritic arborization, migration, and synaptic plasticity. These functions have the overall aim of building a functional brain. They can, however, cause cellular, biochemical, and structural alterations in the neonatal brain [30]. During brain development, the role played by neurotransmitters and their receptors is of primary importance. The distribution and molecular characteristics of Glu receptors change considerably during brain development, making the brain vulnerable to changes in Glu neurotransmission during growth. Indeed, alterations in the expression and regulation of Glu receptors are known to be implicated in some neuropathological conditions such as neurological and psychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, schizophrenia, mood disorders, depression, epilepsy, anxiety, stress, and ASD [31,32,33,34][31][32][33][34]. Studies in animal models of neurologic disease suggest an altered expression of Glu proteins [12,35][12][35]. Knowledge and research on the ontogenetic alterations in Glu receptor function, subunit expression, and binding properties in pathological conditions are still very incomplete. However, in vivo and in vitro studies have provided information about the differences in both regional densities and the time-course of changes in the expression levels of the different Glu receptors subunits (Figure 1) [36].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the developmental time course of glutamatergic receptor subunits expression in different rodent brain areas. The variations in color intensity within the single bars represent changes along time in the expression levels of each receptor subunit in a particular area of the rodent brain. The midbrain, pons, and medulla are represented collectively as brain stem in the figure.

For example, the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) is constituted by tetramers of different subunits (GluR1-4) [37]. The expression pattern of the GluR2 subunit during the period of postnatal development, maturation, and aging in male mice was investigated: it was observed that the expression of the GluR2 subunit is gradually upregulated in the hippocampus from postnatal day 0 (P0) to adult age (20 weeks) and subsequently down-regulated in 70 week-old male mice [38]. GluR1 and GluR4 subunits are expressed at significant levels in the midbrain from embryonic day 15 (E15), they remain constant until delivery, and then decrease immediately after birth, while GluR2 and GluR3 levels increase after early development in the hippocampus [34]. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR) are expressed during the developmental periods of intense synaptic formation. Similar to AMPAR, the expression of the various NMDAR subunits varies over the course of development and in different regions of the brain [39]. Studies in rodents have shown that the GluN1 subunit is expressed before E14 in areas of the brain related to cognitive function, such as the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus. Three weeks after birth, GluN1 levels reach their highest levels and then decrease [40]. The GluN2 subunits are expressed at variable levels at specific stages of neonatal development in rats. In the hippocampus, low levels of GluN2A are detected at P0, while a peak is observed at P21 [41]. As the brain develops, the protein expression of the GluN2A subunit gradually increases. GluN2B is the predominant NMDA receptor subunit located at immature synapses [36]. During prenatal development, it is expressed in the cortex, thalamus, and spinal cord, and its concentrations increase at birth. Lower amounts are expressed in the colliculi, hippocampus, and hypothalamus [34]. After birth, GluN2B levels reach a peak of expression in the cortex and hypothalamus, two important brain structures involved in cognition. The GluN3A subunit is involved in developing dendritic spines and synaptogenesis [34]. This subunit starts to be expressed in the medulla, pons, and hypothalamus at E15 [42,43][42][43]; its levels reach a peak at P8 and then decrease at P20. Kainate-2-carboxy-3-carboxy-methyl-4-isopropenylpyrrolidine receptors (KAR) are expressed at low amounts from E19, during embryonic development, in the cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and striatum [34]. Their activation regulates the network and synaptic activity in the neonatal hippocampus [44,45][44][45]. KAR are widely expressed in the amygdala within the first postnatal week, a period that coincides with the process of synaptogenesis, suggesting its involvement in the process of synapse formation [45]. Rodent studies have demonstrated a low expression at birth of type 1, 2, and 4 Glu metabotropic receptors (mGlu1, mGlu2, mGlu4) that increase during neonatal development [43]. Conversely, at P0, the levels of type 3 and 5 Glu metabotropic receptors, mGlu3 and mGlu5, are very high and then decrease during the maturation period. In fact, both receptors are involved in synaptogenesis, and GRM5 is involved in the proliferation and survival of neural progenitor cells, as well as in the migration of cortical neurons [46]. Another important aspect of the brain development process is the maintenance of the excitation-inhibition (E/I) balance between Glu and Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) [47]. Opposite to Glu, GABA is involved in inhibitory neurotransmission [48]. However, at the beginning of development, GABAergic neurons form excitatory synapses, which become inhibitory only later during the maturation process [49]. For normal brain development and functioning, it is essential that the E/I balance is maintained stably in neuron’s synapses and neural circuits [10,50][10][50]. Consequently, disturbances in the E/I balance have been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD [51,52][51][52].