Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Camila Xu and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

Erythropoietin (Epo) is a 30.4 kDa glycoprotein and pleiotropic cytokine, first described by Carnot in 1906 and isolated by Goldwasser and Kung in 1971, successfully produced for clinical use.

- neuroprotection

- preterm

- Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy

- Erythropoietin

- perinatal stroke

1. Erythropoietin (Epo) Actions and Neuroprotective Effects

Erythropoietin is a 30.4 kDa glycoprotein and pleiotropic cytokine, first described by Carnot in 1906 and isolated by Goldwasser and Kung in 1971, successfully produced for clinical use [1]. During fetal life Epo is produced by the liver, while after birth the production progressively takes place in the peritubular cells of the kidney [2]. Erythropoietin is primarily known for the haematological functions. After an ischemic insult lasting at least 30 min, the transcription of the Hypoxia Inducible Transcription Factor induced by hypoxia determines an increase of Epo hormone production in the kidney [3][4]. Binding of Epo to receptors on erythroid progenitor cells causes an increase in red blood cell mass. The enhanced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood suppress the further expression of Epo completing the feedback loop [5].

The endogenous levels of Epo have been reported to increase in the brain for four hours after hypoxic exposure [6]. Hypoxia induce hypoxia-inducible factor-1, which determines the expression of growth factors such as the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Epo [7]. The immediate effect of Epo is represented by an augmented expression of haemoglobin which improves the oxygen consumption and storage in the hypoxic tissue [5]. Therefore, high serum or amniotic fluid concentrations of Epo may suggest chronic hypoxia in newborns [8]. However, the lack of brain perfusion and oxygenation which occurs in brief periods, but still severe enough to cause brain injury, may not trigger endogenous Epo production [9]. Erythropoietin exerts intracellular protective effects after the ischemia-reperfusion damage, such as decreasing apoptosis, oxidative stress and Blood Brain Barrier (BBB) injury [10]. Furthermore, Epo has been proved to be able to stimulate angiogenesis, neurogenesis and neuronal plasticity after the ischemic damage [11][12].

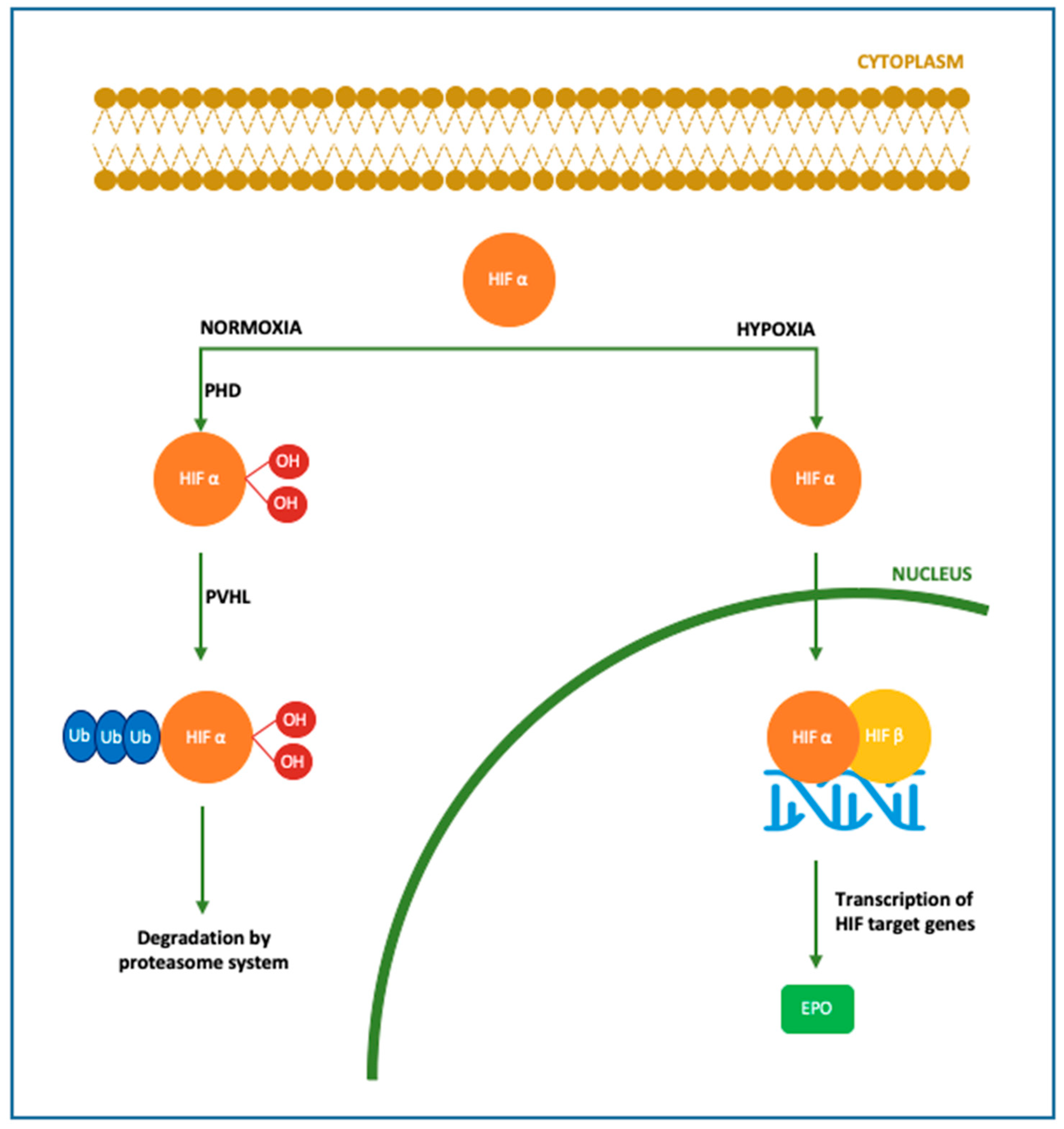

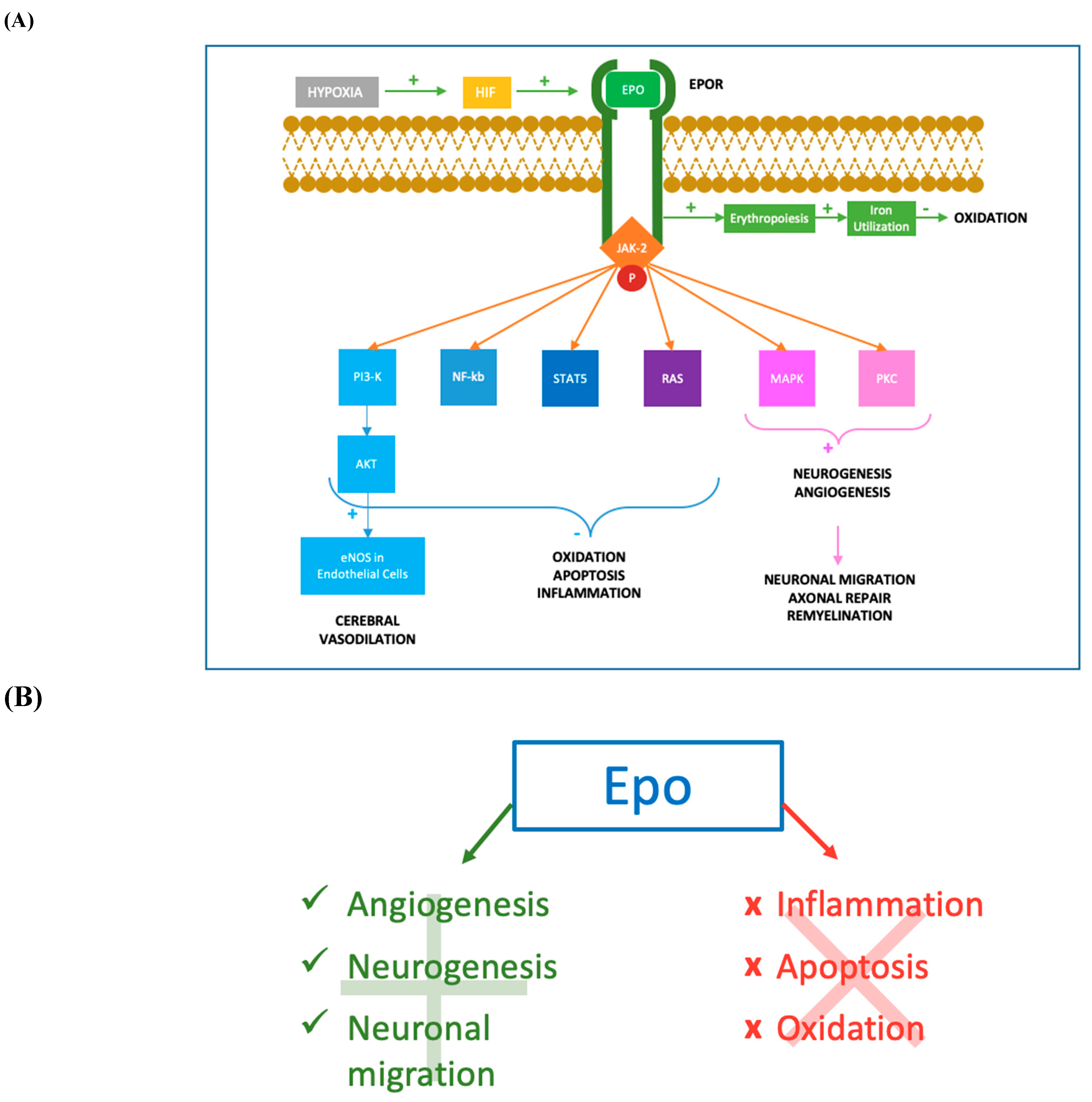

Pleiotropic functions of Epo concerning neuroprotection have been studied in the last few decades. The first evidence for the extra-hematopoietic properties of Epo were published between 1993 and 2000 [13][14]. Normally, only a small percentage of circulating Epo is able to pass the BBB, binding the Epo receptor (EpoR) located on the capillary vessels [15]. However, it has been demonstrated that Epo is also produced in the developing brain, where it acts as a neuroprotective agent and growing factor [16][17][18]. In particular, Epo is primarily produced by astrocytes, followed by oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells, neurons and microglia, induced by hypoxia through the Hypoxia Inducible Transcription Factor pathway [16][17][18]. Figure 1. Both in animal models and in newborns, Epo has shown anti-apoptotic [19][20][21], antioxidant [22][23][24] and anti-inflammatory properties [25][26][27][28][29]. These actions can be exerted directly or mediated by a specific receptor named EpoR, which has been isolated in glial cells, neurons and brain endothelial cells in the hippocampus, cortex internal capsule and midbrain regions [16]. Molecular mechanisms following Epo treatment are shown in Figure 2. When not binding to its ligand, EpoR activates pathways leading to cell death. On the contrary, when Epo is bound to EpoR, cellular survival is promoted [30][31]. In addition, the role of Epo has also been described in promoting angiogenesis [20][32][33], oligodendrogenesis and neurogenesis [34][35][36][37]. In most of clinical studies, Epo is given in the form of recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEpo), which was the first purified and cloned [38]. Considering the difficulties in obtaining a sufficient quantity of Epo from the blood serum of living humans, rhEpo is produced in higher quantities from cultured mammalian hamster ovary cells and is highly purified [38][39]. At least nine isoforms of rhEpo can be identified, among which are epoetin alfa/alpha/beta, darbepoetin (Darbe) and carbamylated Epo [40]. Darbe is an analog of Epo with an additional sialic acid, able to confer a three-fold longer serum half-life compared with epoetin alfa, the most used isoform [41]. Epo and Darbe are termed as erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) [42].

Figure 1. Molecular mechanism of Epo production. In the brain Epo production is upregulated by oxygen levels mainly in astrocytes, followed by oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells and microglia. In case of normoxia, cytoplasmic HIFα is hydroxylated and polyubiquitinated by PHD and pVHL, respectively. In this form, HIF is degraded by the proteasome system. In case of hypoxia, HIFα is dehydroxylated and deubiquinated, thus able to translocate into the nucleus and bind HIF β, inducing the transcription of its target genes among which Epo gene [16][17][18][43]. HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; PHD: prolyl-4-hydroxylases; PVHL: von Hippel–Lindau protein.

Figure 1. Molecular mechanism of Epo production. In the brain Epo production is upregulated by oxygen levels mainly in astrocytes, followed by oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells and microglia. In case of normoxia, cytoplasmic HIFα is hydroxylated and polyubiquitinated by PHD and pVHL, respectively. In this form, HIF is degraded by the proteasome system. In case of hypoxia, HIFα is dehydroxylated and deubiquinated, thus able to translocate into the nucleus and bind HIF β, inducing the transcription of its target genes among which Epo gene [16][17][18][43]. HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; PHD: prolyl-4-hydroxylases; PVHL: von Hippel–Lindau protein.

Figure 2. Molecular mechanisms of Epo action. (A) After hypoxia, the production of HIF determines an augmented synthesis of Epo which binds to its transmembrane receptor EpoR. The cytoplasmic tail of the Epo-EpoR complex phosphorylates JAK2, which activates a complex cascade of signalling pathways. The activation of PI3K/AKT pathway leads to the increase of eNOS activity in endothelial cells, determining augmented levels of NO and cerebral vasodilation. PI3K/AKT, together with NF-kb, STAT-5 and RAS pathways, reduces inflammation, oxidation and apoptosis acting both at nuclear and intramitochondrial levels. Moreover, MAPK and PKC mediated mechanisms promote neurogenesis and angiogenesis in damaged tissues. Neurogenesis, especially oligodendrogenesis, facilitates the process of remyelination and axonal repair, while angiogenesis permits flow restoration and migration of neuronal progenitors in the ischemic areas. The erythropoietic effect of Epo-EpoR binding is an additional antioxidant mechanism, increasing iron utilization resulting in a lower iron oxidant potential. JAK-2: Janus-tyrosine-kinase-2; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT: v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO: nitric oxide; NF-kb: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; STAT-5: signal transducer and activator of transcription 5; RAS: rat sarcoma; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; PKC: protein kinase C. (B) Mechanisms promoted and inhibited following Epo treatment. Epo has shown anti-apoptotic [19][20][21], antioxidant [22][23][24] and anti-inflammatory properties [25][26][27][28][29]. Epo promotes angiogenesis [20][32][33], oligodendrogenesis, neuronal progenitors migration in the ischemic areas (Wang et al., 2004; Ohab et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007) and neurogenesis [34][35][36][37].

Figure 2. Molecular mechanisms of Epo action. (A) After hypoxia, the production of HIF determines an augmented synthesis of Epo which binds to its transmembrane receptor EpoR. The cytoplasmic tail of the Epo-EpoR complex phosphorylates JAK2, which activates a complex cascade of signalling pathways. The activation of PI3K/AKT pathway leads to the increase of eNOS activity in endothelial cells, determining augmented levels of NO and cerebral vasodilation. PI3K/AKT, together with NF-kb, STAT-5 and RAS pathways, reduces inflammation, oxidation and apoptosis acting both at nuclear and intramitochondrial levels. Moreover, MAPK and PKC mediated mechanisms promote neurogenesis and angiogenesis in damaged tissues. Neurogenesis, especially oligodendrogenesis, facilitates the process of remyelination and axonal repair, while angiogenesis permits flow restoration and migration of neuronal progenitors in the ischemic areas. The erythropoietic effect of Epo-EpoR binding is an additional antioxidant mechanism, increasing iron utilization resulting in a lower iron oxidant potential. JAK-2: Janus-tyrosine-kinase-2; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT: v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO: nitric oxide; NF-kb: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; STAT-5: signal transducer and activator of transcription 5; RAS: rat sarcoma; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; PKC: protein kinase C. (B) Mechanisms promoted and inhibited following Epo treatment. Epo has shown anti-apoptotic [19][20][21], antioxidant [22][23][24] and anti-inflammatory properties [25][26][27][28][29]. Epo promotes angiogenesis [20][32][33], oligodendrogenesis, neuronal progenitors migration in the ischemic areas (Wang et al., 2004; Ohab et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007) and neurogenesis [34][35][36][37].

2. Erythropoietin in Preterm Infants

Erythropoietin has been administered to preterm infants since 1990 for haematological purposes. In fact, Epo has been extensively used for the prevention of anemia of prematurity, but the discovery of the potential role as a neuroprotective agent suggested new purposes for its administration [44][45][46]. In the last few decades the survival of preterm infants has dramatically grown, yet this population is still exposed to a great incidence of neurodevelopmental impairment [47][48]. Trials conducted in animal models have shown neuroprotective effects of Epo, thus clinical studies investigating Epo’s new potential benefits in premature babies have followed [49][50][51][52][53]. In particular, it has been described that Epo administration in preterm is able to protect neurons and oligodendrocytes from apoptosis, prevent inflammation and promote neurogenesis and angiogenesis [54][55]. Preterm infants benefit by a prolonged treatment during the period of oligodendrocyte maturation, between 24 and 32 weeks [49][56][57], in which Epo exerts a neuroprotective function. Evidence in newborns and animal models suggest neuroprotective effects at doses >200 U/kg [58]. Cumulative doses have been associated with more beneficial effects compared to a single-dose administration [59]. The dosage of EPO ranged from 250 to 3000 UI/kg in all studies. Darbe alfa was administered at 10 mcg/Kg sc [60][61][62]. The population target was represented of extremely and very preterm babies (gestational age below 32 weeks or BW < 1500 gr). Only three clinical trials focused on the role of Epo in extremely preterm infants (gestational age below 28 weeks or 1000 gr) [63][64][65]. Erythropoietin administration was proved to be safe in all preterm infants, not affecting mortality rate and major adverse effects occurrence in the short and long term [64][65][66]. These data confirmed previous analyses on animal models [59][67][68]. Out of 16, 10 trials performed clinical neurodevelopmental outcome evaluated mainly in the first years of life. No uniform results were reported. In addition, neurodevelopmental outcomes were not assessed in all trials in which neuroimaging was performed. It has been well recognized that a correlation between white matter injuries and neurodevelopmental outcome, in terms of increased incidence of cerebral palsy, motor and cognitive delay exists [69][70][71][72]. In addition, values of fractional anisotropy of the corpus callosum assessed using TBSS have been reported to directly correlate with motor and cognitive outcomes [73]. Thus, neuroimaging alterations have been related with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes [41][60][61][74][75]. Studies on Epo treated very preterm newborns highlighted an improved white matter development and a weak but widespread effect in the overall structural connectivity network after Epo treatment [76][77]. Yet, no difference for any brain metabolite has been reported in very preterm treated group [61].3. Erythropoietin in HIE

After several years of studies conducted in animal models, in 2009 the first trial of Epo administration as adjuvant therapy with TH in newborns affected by HIE was published. The research underlined Epo favourable effects, paving the way to further studies [78]. Since then Epo showed beneficial effects during the secondary energy failure and the tertiary phases of HIE [79]. The therapeutic scheme is influenced by the type of damage [56]. In HIE term newborns high Epo doses are more effective when the injury has not been established yet [49][56][57]. Evidence from animal models have shown that Epo should be administered at high doses within 6 h after the onset of brain injury to reach a substantial neuroprotective effect [80]. In this context, Epo may influence the mechanisms of cerebral flow restoration, neovascularization and neuroregeneration, limiting the ischemic damage [81]. OurThe analysis revealed that Epo administration was safe and well tolerated [78], confirming previous findings in animal models [51][59][68]. The passage through the BBB is an essential issue to be considered for any neuroprotective drug given systemically. Erythropoietin presents a molecular weight too high to be carried across the BBB through the lipid mediated transport [78]. Transport of Epo through the BBB is mediated by a specific receptor-facilitated process [15] as well as a time, dose and peak serum concentration-dependent mechanism [82][83]. Furthermore, the alteration of BBB permeability caused by asphyxia determines in patient with HIE an easier passage from serum to cerebrospinal fluid [84]. In the studies analysed, Epo administration is followed by a higher concentration of Epo in the cerebrospinal fluid compared to HIE controls, thus confirming the increased levels are due to the contribution of Epo exogenous administration [78]. Administration of Epo has shown some advantages compared to TH treatment. Treatment with Epo implies easier technical performance, with less side effects [78][85]. Moreover, Epo treatment is effective if administered within 48 h of life, differently from TH which must be initiated within the first 6 h of life [78]. Thus, Epo treatment has been proposed as both an alternative therapy or combined treatment with TH [78][85]. In all the protocols comparing Epo vs. placebo or Epo associated with TH vs. supportive therapy, Epo treatment determined a lower death rate and improved neurologic outcomes [85][86][87][88][89][90]. Valera et al. treated 15 HIE neonates with EPO for two weeks, starting within three hours from birth along with TH. At 18 months, there was 80% survival with no neurodevelopmental disability. Unfortunately, there was no control group for comparison [91]. Rogers et al. recruited 24 newborns with HIE and administered Epo 24 h after HIE combined with standard TH. The researchers found that significant neurodevelopmental disability occurred in only 12.5% of infants with moderate to severe MRI changes who received Epo plus TH, compared to 70–80% significant disability or death in infants treated with TH alone. However, these results were not statistically significant as the number of infants was too small [92]. The Phase II clinical trial on newborns with HIE reported better 12-months motor outcomes for treatment with Epo plus TH compared to TH alone [90]. A randomized case-control study by Wu et al. [89] evaluating 24 newborns treated with Epo and TH for moderate/severe HIE, showed a significantly reduced brain injury on MRI at 5 days-of-age and better 12-months motor outcomes compared to the 26 infants who received TH as a standard routine measure for HIE. The Epo treatment was also associated with an antioxidant effect and an increase of neuroprotective factors [85][86]. The study by Wang et al. clearly demonstrated the protection from the damage resulting from asphyxia through inhibiting apoptosis, reducing oxygen free radicals and enhancing antioxidant capacity. In this research trial, 34 newborns received Epo and Vitamin C plus TH compared to 34 newborns receiving conventional treatment plus ascorbic acid. There were lower oxidative stress index levels and higher antioxidant enzymes in both groups after treatment, with better results in the group treated with Epo. Moreover, lower pro-apoptotic molecules and higher anti-apoptotic molecules were found in both groups after treatment, with better results again in the group treated with Epo [93]. In addition, MRI analysis confirmed the beneficial effect of Epo in the reduction of brain injury, both if administered alone [87] or combined with TH [90]. Despite all these data, the optimal dosage and administration regimens for the treatment of HIE in newborns still needs to be defined [78][85][92].4. Erythropoietin in Neonatal Stroke

At the diagnosis of neonatal stroke, the damage has already been established and the reparation mechanisms are not fully known, thus nowadays acute therapies for perinatal strokes are still not available [94]. Currently the management of the disease is mainly supportive, based on the treatment of complications, such as antiepileptic therapy, and on the improvement of neurologic chronic sequelae through rehabilitation [95]. Erythropoietin has become one of the most remarkable neuroprotective strategy since Sakanaka et al. reported for the first time the role of Epo as a neuroprotective agent in the ischemic brain damage [96]. Recent researches are focused on new approaches including the administration of adjuvant neuroprotective therapies, with the aim to enhance endogenous mechanisms of repair and angiogenesis [97][98]. The safety profile of Epo administration was also confirmed in the studies on neonatal stroke. This is consistent with previous data available from animal models and preterm and HIE-suffering newborns, which showed a good tolerance of treatment with Epo in those populations [45][80][99][100]. The brain MRI evaluation in both studies didn’t find a beneficial effect of Epo treatment on stroke volume [101][102]. Furthermore, Epo treatment was not associated with an overall difference in neurodevelopmental outcome, at 3 months and one year follow up respectively with Griffiths’ scale and BSID-III [101][102]. These data are in contrast with most of the newborn stroke animal models in which several neuroprotective effects and reduction of stroke volume induced by Epo are described [7][49][103][104]. Recently, a delayed Epo therapy administered to mice model with middle brain artery occlusion stroke reported to uphold brain volume and to improve behavioural and sensorimotor functions, compared with placebo-treated animals [7]. The discrepancy between the experimental animal model and clinical trials may be due to the small neonatal study population, as the trials are both phase I and II studies. Furthermore, Andropoulos and colleagues found that six enrolled newborns presented microdeletions at the chromosome 22q11.2 region, a condition known to be linked to a variable degree on neurodevelopmental impairment in a syndromic condition [105]. Another limiting factor is the therapeutic window, as the beneficial effect is limited to specific time after injury [106]. One interventional study used Epo after stroke diagnosis, which is usually done 24–48 h after cerebral vascular accident. The use of specific biomarkers that will increase within the first hours of life in hypoxic-ischemic injury may help in the early diagnosis of stroke, allowing a prompt identification of neonates who may qualify for neuroprotection. Finally, the variability in period and tests used to assess the neurodevelopmental outcome may represent a weakness and suggests that scores should be interpreted with caution. Since the determinants of cognitive outcomes at school age are multifactorial, the predictive value of tests administered at age < 24 months might never approach 100%.References

- Goldwasser, E.; Kung, C. Purification of erythropoietin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 697–698.

- Juul, S.; Pet, G. Erythropoietin and Neonatal Neuroprotection. Clin. Perinatol. 2015, 42, 469–481.

- Ivan, M.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Kim, W.; Valiando, J.; Ohh, M.; Salic, A.; Asara, J.M.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, W.G.J. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: Implications for O2 sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468.

- Jaakkola, P.; Mole, D.R.; Tian, Y.M.; Wilson, M.I.; Gielbert, J.; Gaskell, S.J.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Hebestreit, H.F.; Mukherji, M.; Schofield, C.J.; et al. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 2001, 292, 468–472.

- Fisher, J.W. Erythropoietin: Physiology and pharmacology update. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003, 228, 1–14.

- Chikuma, M.; Masuda, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Nagao, M.; Sasaki, R. Tissue-specific regulation of erythropoietin production in the murine kidney, brain, and uterus. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 279, E1242–E1248.

- Larpthaveesarp, A.; Georgevits, M.; Ferriero, D.M.; Gonzalez, F.F. Delayed Erythropoietin Therapy Improves Histological and Behavioral Outcomes after Transient Neonatal Stroke. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 57–63.

- Teramo, K.A.; Widness, J.A. Increased fetal plasma and amniotic fluid erythropoietin concentrations: Markers of intrauterine hypoxia. Neonatology 2009, 95, 105–116.

- Traudt, C.M.; McPherson, R.J.; Bauer, L.A.; Richards, T.L.; Burbacher, T.M.; McAdams, R.M.; Juul, S.E. Concurrent erythropoietin and hypothermia treatment improve outcomes in a term nonhuman primate model of perinatal asphyxia. Dev. Neurosci. 2013, 35, 491–503.

- Zhang, S.-J.; Luo, Y.-M.; Wang, R.-L. The effects of erythropoietin on neurogenesis after ischemic stroke. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2020, 19, 561–570.

- Xiong, T.; Qu, Y.; Mu, D.; Ferriero, D. Erythropoietin for neonatal brain injury: Opportunity and challenge. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. Off. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Neurosci. 2011, 29, 583–591.

- Sargin, D.; El-Kordi, A.; Agarwal, A.; Müller, M.; Wojcik, S.M.; Hassouna, I.; Sperling, S.; Nave, K.-A.; Ehrenreich, H. Expression of constitutively active erythropoietin receptor in pyramidal neurons of cortex and hippocampus boosts higher cognitive functions in mice. BMC Biol. 2011, 9, 27.

- Li, Y.; Juul, S.E.; Morris-Wiman, J.A.; Calhoun, D.A.; Christensen, R.D. Erythropoietin receptors are expressed in the central nervous system of mid-trimester human fetuses. Pediatr. Res. 1996, 40, 376–380.

- Morishita, E.; Masuda, S.; Nagao, M.; Yasuda, Y.; Sasaki, R. Erythropoietin receptor is expressed in rat hippocampal and cerebral cortical neurons, and erythropoietin prevents in vitro glutamate-induced neuronal death. Neuroscience 1997, 76, 105–116.

- Brines, M.L.; Ghezzi, P.; Keenan, S.; Agnello, D.; De Lanerolle, N.C.; Cerami, C.; Itri, L.M.; Cerami, A. Erythropoietin crosses the blood—Brain barrier to protect against experimental brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10526–10531.

- Juul, S.; Anderson, D.; Li, Y.; Christensen, R. Erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in the developing human central nervous system. Pediatr. Res. 1998, 43, 40–49.

- Ott, C.; Martens, H.; Hassouna, I.; Oliveira, B.; Erck, C.; Zafeiriou, M.-P.; Peteri, U.-K.; Hesse, D.; Gerhart, S.; Altas, B.; et al. Widespread Expression of Erythropoietin Receptor in Brain and Its Induction by Injury. Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 803–815.

- Masuda, S.; Okano, M.; Yamagishi, K.; Nagao, M.; Uedas, M. A Novel Site of Erythropoietin Production. Oxygen-dependent production in cultured rat astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 19488–19493.

- Sirén, A.L.; Fratelli, M.; Brines, M.; Goemans, C.; Casagrande, S.; Lewczuk, P.; Keenan, S.; Gleiter, C.; Pasquali, C.; Capobianco, A.; et al. Erythropoietin prevents neuronal apoptosis after cerebral ischemia and metabolic stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4044–4049.

- Ghezzi, P.; Brines, M. Erythropoietin as an antiapoptotic, tissue-protective cytokine. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11 (Suppl. 1), S37–S44.

- Merelli, A.; Czornyj, L.; Lazarowski, A. Erythropoietin as a new therapeutic opportunity in brain inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Neurosci. 2015, 125, 793–797.

- Bailey, D.M.; Lundby, C.; Berg, R.M.G.; Taudorf, S.; Rahmouni, H.; Gutowski, M.; Mulholland, C.W.; Sullivan, J.L.; Swenson, E.R.; McEneny, J.; et al. On the antioxidant properties of erythropoietin and its association with the oxidative-nitrosative stress response to hypoxia in humans. Acta Physiol. 2014, 212, 175–187.

- Genc, S.; Akhisaroglu, M.; Kuralay, F.; Genc, K. Erythropoietin restores glutathione peroxidase activity in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced neurotoxicity in C57BL mice and stimulates murine astroglial glutathione peroxidase production in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 2002, 321, 73–76.

- Akisu, M.; Tuzun, S.; Arslanoglu, S.; Yalaz, M.; Kultursay, N. Effect of recombinant human erythropoietin administration on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme(s) activities in preterm infants. Acta Med. Okayama 2001, 55, 357–362.

- Zhou, Z.-W.; Li, F.; Zheng, Z.-T.; Li, Y.-D.; Chen, T.-H.; Gao, W.-W.; Chen, J.-L.; Zhang, J.-N. Erythropoietin regulates immune/inflammatory reaction and improves neurological function outcomes in traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav. 2017, 7, e00827.

- Wei, S.; Luo, C.; Yu, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, C.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, L.; Yi, B. Erythropoietin ameliorates early brain injury after subarachnoid haemorrhage by modulating microglia polarization via the EPOR/JAK2-STAT3 pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 361, 342–352.

- Agnello, D.; Bigini, P.; Villa, P.; Mennini, T.; Cerami, A.; Brines, M.L.; Ghezzi, P. Erythropoietin exerts an anti-inflammatory effect on the CNS in a model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res. 2002, 952, 128–134.

- Genc, K.; Genc, S.; Baskin, H.; Semin, I. Erythropoietin decreases cytotoxicity and nitric oxide formation induced by inflammatory stimuli in rat oligodendrocytes. Physiol. Res. 2006, 55, 33–38.

- Robinson, S.; Winer, J.L.; Berkner, J.; Chan, L.A.S.; Denson, J.L.; Maxwell, J.R.; Yang, Y.; Sillerud, L.O.; Tasker, R.C.; Meehan, W.P., 3rd; et al. Imaging and serum biomarkers reflecting the functional efficacy of extended erythropoietin treatment in rats following infantile traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2016, 17, 739–755.

- Jantzie, L.; Miller, R.; Robinson, S. Erythropoietin Signaling Promotes Oligodendrocyte Development Following Prenatal Systemic Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. Pediatr. Res. 2013, 74, 658–667.

- Jantzie, L.L.; Corbett, C.J.; Firl, D.J.; Robinson, S. Postnatal Erythropoietin Mitigates Impaired Cerebral Cortical Development Following Subplate Loss from Prenatal Hypoxia—Ischemia. Cereb Cortex 2015, 25, 2683–2695.

- Li, Y.; Lu, Z.; Keogh, C.; Yu, S.; Wei, L. Erythropoietin-induced neurovascular protection, angiogenesis, and cerebral blood flow restoration after focal ischemia in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007, 27, 1043–1054.

- Cantarelli, C.; Angeletti, A.; Cravedi, P. Erythropoietin, a multifaceted protein with innate and adaptive immune modulatory activity. Am. J. Transpl. 2019, 19, 2407–2414.

- Mazur, M.; Miller, R.H.; Robinson, S. Postnatal erythropoietin treatment mitigates neural cell loss after systemic prenatal hypoxic-ischemic injury. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2010, 6, 206–221.

- Knabe, W.; Knerlich, F.; Washausen, S.; Kietzmann, T.; Sirén, A.L.; Brunnett, G.; Kuhn, H.J.; Ehrenreich, H. Expression patterns of erythropoietin and its receptor in the developing midbrain. Anat. Embryol. 2004, 207, 503–512.

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chopp, M. Treatment of stroke with erythropoietin enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis and improves neurological function in rats. Stroke 2004, 35, 1732–1737.

- Park, M.H.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, J.W.; Son, D.J.; Moon, D.C.; Yoon, D.Y.; Hong, J.T. ERK-mediated production of neurotrophic factors by astrocytes promotes neuronal stem cell differentiation by erythropoietin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 339, 1021–1028.

- Ng, T.; Marx, G.; Littlewood, T.; Macdougall, I. Recombinant erythropoietin in clinical practice. Postgrad. Med. J. 2003, 79, 367–376.

- Inoue, N.; Takeuchi, M.; Ohashi, H.; Suzuki, T. The production of recombinant human erythropoietin. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 1995, 1, 297–313.

- Sirén, A.-L.; Fasshauer, T.; Bartels, C.; Ehrenreich, H. Therapeutic potential of erythropoietin and its structural or functional variants in the nervous system. Neurotherapeutics 2009, 6, 108–127.

- Smith, R.E.J.; Jaiyesimi, I.A.; Meza, L.A.; Tchekmedyian, N.S.; Chan, D.; Griffith, H.; Brosman, S.; Bukowski, R.; Murdoch, M.; Rarick, M.; et al. Novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (NESP) for the treatment of anaemia of chronic disease associated with cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 84 (Suppl. 1), 24–30.

- Maxwell, J.R.; Ohls, R.K. Update on Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents Administered to Neonates for Neuroprotection. Neoreviews 2019, 20, e622–e635.

- Lee, J.W.; Ko, J.; Ju, C.; Eltzschig, H.K. Hypoxia signaling in human diseases and therapeutic targets. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–13.

- Shannon, K.M.; Mentzer, W.C.; Abels, R.I.; Freeman, P.; Newton, N.; Thompson, D.; Sniderman, S.; Ballard, R.; Phibbs, R.H. Recombinant human erythropoietin in the anemia of prematurity: Results of a placebo-controlled pilot study. J. Pediatr. 1991, 118, 949–955.

- Maier, R.F.; Obladen, M.; Scigalla, P.; Linderkamp, O.; Duc, G.; Hieronimi, G.; Halliday, H.L.; Versmold, H.T.; Moriette, G.; Jorch, G. The effect of epoetin beta (recombinant human erythropoietin) on the need for transfusion in very-low-birth-weight infants. European Multicentre Erythropoietin Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 1173–1178.

- Ahmad, K.; Bennett, M.; Juul, S.; Ohls, R.; Clark, R.; Tolia, V. Utilization of Erythropoietin within the United States Neonatal Intensive Care Units from 2008 to 2017. Am. J. Perinatol. 2021, 38, 734–740.

- Latal, B. Prediction of neurodevelopmental outcome after preterm birth. Pediatr. Neurol. 2009, 40, 413–419.

- Saigal, S.; Doyle, L. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 2008, 371, 261–269.

- Iwai, M.; Stetler, R.; Xing, J.; Hu, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Cao, G. Enhanced Oligodendrogenesis and Recovery of Neurological Function by Erythropoietin following Neonatal Hypoxic/Ischemic Brain Injury. Stroke 2010, 41, 1032–1037.

- Iwai, M.; Cao, G.; Yin, W.; Stetler, R.A.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Erythropoietin promotes neuronal replacement through revascularization and neurogenesis after neonatal hypoxia/ischemia in rats. Stroke 2007, 38, 2795–2803.

- Keller, M.; Yang, J.; Griesmaier, E.; Gorna, A.; Sarkozy, G.; Urbanek, M.; Gressens, P.; Simbruner, G. Erythropoietin is neuroprotective against NMDA-receptor-mediated excitotoxic brain injury in newborn mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 24, 357–366.

- Rees, S.; Hale, N.; De Matteo, R.; Cardamone, L.; Tolcos, M.; Loeliger, M.; Mackintosh, A.; Shields, A.; Probyn, M.; Greenwood, D.; et al. Erythropoietin is neuroprotective in a preterm ovine model of endotoxin-induced brain injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 306–319.

- Zhu, L.; Huang, L.; Wen, Q.; Wang, T.; Qiao, L.; Jiang, L. Recombinant human erythropoietin offers neuroprotection through inducing endogenous erythropoietin receptor and neuroglobin in a neonatal rat model of periventricular white matter damage. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 650, 12–17.

- Shingo, T.; Sorokan, S.T.; Shimazaki, T.; Weiss, S. Erythropoietin regulates the in vitro and in vivo production of neuronal progenitors by mammalian forebrain neural stem cells. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 9733–9743.

- Juul, S. Neuroprotective role of erythropoietin in neonates. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2012, 25 (Suppl. 4), 105–107.

- Tataranno, M.L.; Perrone, S.; Longini, M.; Buonocore, G. New Antioxidant Drugs for Neonatal Brain Injury. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 108251.

- Reitmeir, R.; Kilic, E.; Kilic, U.; Bacigaluppi, M.; ElAli, A.; Salani, G.; Pluchino, S.; Gassmann, M.; Hermann, D. Post-acute delivery of erythropoietin induces stroke recovery by promoting perilesional tissue remodelling and contralesional pyramidal tract plasticity. Brain 2011, 134 Pt 1, 84–99.

- Newton, N.; Leonard, C.; Piecuch, R.; Phibbs, R. Neurodevelopmental outcome of prematurely born children treated with recombinant human erythropoietin in infancy. J. Perinatol. 1999, 19, 403–406.

- Kellert, B.A.; Mcpherson, R.J.; Juul, S.E. A Comparison of High-Dose Recombinant Erythropoietin Treatment Regimens in Brain-Injured Neonatal Rats. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 61, 451–455.

- Lowe, J.R.; Rieger, R.E.; Moss, N.C.; Yeo, R.A.; Winter, S.; Patel, S.; Phillips, J.; Campbell, R.; Baker, S.; Gonzales, S.; et al. Impact of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents on Behavioral Measures in Children Born Preterm. J. Pediatr. 2017, 184, 75–80.e1.

- Gasparovic, C.; Caprihan, A.; Yeo, R.; Phillips, J.; Lowe, J.; Campbell, R.; Ohls, R. The long-term effect of erythropoiesis stimulating agents given to preterm infants: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study on neurometabolites in early childhood. Pediatr. Radiol. 2018, 48, 374–382.

- Ohls, R.; Kamath-Rayne, B.; Christensen, R.; Wiedmeier, S.; Rosenberg, A.; Fuller, J.; Lacy, C.; Roohi, M.; Lambert, D.; Burnett, J.; et al. Cognitive Outcomes of Preterm Infants Randomized to Darbepoetin, Erythropoietin, or Placebo. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 1023–1030.

- Neubauer, A.; Voss, W.; Wachtendorf, M.; Jungmann, T. Erythropoietin Improves Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Extremely Preterm Infants. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 67, 657–666.

- McAdams, R.; McPherson, R.; Mayock, D.; Juul, S. Outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants given early high- dose erythropoietin. J. Perinatol. 2013, 33, 226–230.

- Juul, S.; Comstock, B.; Wadhawan, R.; Mayock, D.; Courtney, S.; Robinson, T.; Ahmad, K.; Bendel-Stenzel, E.; Baserga, M.; LaGamma, E.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Erythropoietin for Neuroprotection in Preterm Infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 233–243.

- Fauchère, J.; Koller, B.; Tschopp, A.; Dame, C.; Ruegger, C.; Bucher, H.; Group, S.E.N.T. Safety of Early High-Dose Recombinant Erythropoietin for Neuroprotection in Very Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 52–57.

- Lee, H.S.; Song, J.; Min, K.; Choi, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-M.; Cho, S.-R.; Kim, M. Short-term effects of erythropoietin on neurodevelopment in infants with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Brain Dev. 2014, 36, 764–769.

- McPherson, R.J.; Demers, E.J.; Juul, S.E. Safety of high-dose recombinant erythropoietin in a neonatal rat model. Neonatology 2007, 91, 36–43.

- Woodward, L.; Anderson, P.; Austin, N.; Howard, K.; Inder, T. Neonatal MRI to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 685–694.

- Rutherford, M.; Supramaniam, V.; Ederies, A.; Chew, A.; Bassi, L.; Groppo, M.; Anjari, M.; Counsell, S.; Ramenghi, L. Magnetic resonance imaging of white matter diseases of prematurity. Neuroradiology 2010, 52, 505–521.

- de Bruïne, F.; van den Berg-Huysmans, A.; Leijser, L.; Rijken, M.; Steggerda, S.; van der Grond, J.; van Wezel-Meijler, G. Clinical implications of MR imaging findings in the white matter in very preterm infants: A 2-year follow-up study. Radiology 2011, 261, 899–906.

- Ment, L.; Hirtz, D.; Hüppi, P. Imaging biomarkers of outcome in the developing preterm brain. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 1042–1055.

- van Kooij, B.; de Vries, L.; Ball, G.; van Haastert, I.; Benders, M.; Groenendaal, F.; Counsell, S. Neonatal tract-based spatial statistics findings and outcome in preterm infants. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2012, 33, 188–194.

- O’Gorman, R.; Bucher, H.; Held, U.; Koller, B.; Hüppi, P.; Hagmann, C.; Swiss EPO Neuroprotection Trial Group. Tract-based spatial statistics to assess the neuroprotective effect of early erythropoietin on white matter development in preterm infants. Brain 2015, 138, 388–397.

- Porter, E.; Counsell, S.; Edwards, A.; Allsop, J.; Azzopardi, D. Tract-based spatial statistics of magnetic resonance images to assess disease and treatment effects in perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. Pediatr. Res. 2010, 68, 205–209.

- Yang, S.-S.; Xu, F.-L.; Cheng, H.-Q.; Xu, H.-R.; Yang, L.; Xing, J.-Y.; Cheng, L. . Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2018, 20, 346–351.

- Jakab, A.; Ruegger, C.; Bucher, H.U.; Malek, M.; Huppi, P.S.; Tuura, R.; Hagmann, C. Network based statistics reveals trophic and neuroprotective effect of early high dose erythropoetin on brain connectivity in very preterm infants. NeuroImage Clin. 2019, 22.

- Zhu, C.; Kang, W.; Xu, F.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, L.; Ji, L.; Guo, X.; Simbruner, G.; Blomgren, K.; et al. Erythropoietin Improved Neurologic Outcomes in Newborns With Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 218–226.

- Solevåg, A.L.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Cheung, P. Novel interventions to reduce oxidative-stress related brain injury in neonatal asphyxia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 142, 113–122.

- Fauchère, J.; Dame, C.; Vonthein, R.; Koller, B.; Arri, S.; Wolf, M.; Bucher, H. An approach to using recombinant erythropoietin for neuroprotection in very preterm infants. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 375–382.

- Lv, H.-Y.; Wu, S.-J.; Wang, Q.-L.; Yang, L.-H.; Ren, P.-S.; Qiao, B.-J.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Li, J.-H.; Gu, X.-L.; Li, L.-X. Effect of erythropoietin combined with hypothermia on serum tau protein levels and neurodevelopmental outcome in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neural Regen. Res. 2017, 12, 1655–1663.

- Xenocostas, A.; Cheung, W.K.; Farrell, F.; Zakszewski, C.; Kelley, M.; Lutynski, A.; Crump, M.; Lipton, J.H.; Kiss, T.L.; Lau, C.Y.; et al. The pharmacokinetics of erythropoietin in the cerebrospinal fluid after intravenous administration of recombinant human erythropoietin. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 61, 189–195.

- Juul, S.E.; McPherson, R.J.; Farrell, F.X.; Jolliffe, L.; Ness, D.J.; Gleason, C.A. Erytropoietin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of nonhuman primates and fetal sheep following high-dose recombinant erythropoietin. Biol. Neonate 2004, 85, 138–144.

- Statler, P.A.; McPherson, R.J.; Bauer, L.A.; Kellert, B.A.; Juul, S.E. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose recombinant erythropoietin in plasma and brain of neonatal rats. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 61, 671–675.

- El Shimi, M.; Awad, H.; Hassanein, S.; Gad, G.; Imam, S.; Shaaban, H.; El Maraghy, M. Single dose recombinant erythropoietin versus moderate hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in low resource settings. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014, 27, 1295–1300.

- Avasiloaiei, A.; Dimitriu, C.; Moscalu, M.; Paduraru, L.; Stamatin, M. High-dose phenobarbital or erythropoietin for the treatment of perinatal asphyxia in term newborns. Pediatr. Int. 2013, 55, 589–593.

- Malla, R.R.; Asimi, R.; Teli, M.A.; Shaheen, F.; Bhat, M.A. Erythropoietin monotherapy in perinatal asphyxia with moderate to severe encephalopathy: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Perinatol. 2017, 37, 596–601.

- Wang, Y.-J.; Pan, K.-L.; Zhao, X.-L.; Qiang, H.; Cheng, S.-Q. Therapeutic effects of erythropoietin on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in neonates. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2011, 13, 855–858.

- Wu, Y.; Mathur, A.; Chang, T.; McKinstry, R.; Mulkey, S.; Mayock, D.; Van Meurs, K.; Rogers, E.; Gonzalez, F.; Comstock, B.; et al. High-dose Erythropoietin and Hypothermia for Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy: A Phase II Trial. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20160191.

- Mulkey, S.B.; Ramakrishnaiah, R.H.; Mckinstry, R.C.; Chang, T.; Mathur, A.M.; Mayock, D.E.; Van Meurs, K.P.; Schaefer, G.B.; Luo, C.; Bai, S.; et al. Erythropoietin and Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy: Volume of Acute Brain Injury and 1-Year Neurodevelopmental Outcome. J. Pediatr. 2017, 3–6.

- Valera, I.; Vázquez, M.; González, M.; Jaraba, M.; Benítez, M.; Moraño, C.; Laso, E.; Cabañas, J.; Quiles, M. Erythropoietin with hypothermia improves outcomes in neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2015, 4, 244–249.

- Rogers, E.E.; Bonifacio, S.L.; Glass, H.C.; Juul, S.E.; Chang, T.; Mayock, D.E.; Durand, D.J.; Song, D.; Barkovich, A.J.; Ballard, R.A.; et al. Pediatric Neurology Erythropoietin and Hypothermia for Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Pediatr. Neurol. 2014, 51, 657–662.

- Wang, S. Effect of mild hypothermia combined with VitC and EPO therapy on target organ damage in children with neonatal asphyxia. J. Hainan Med. Univ. 2017, 23, 117–120.

- Monagle, P.; Chan, A.K.C.; Goldenberg, N.A.; Ichord, R.N.; Journeycake, J.M.; Nowak-Göttl, U.; Vesely, S.K. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012, 141, e737S–e801S.

- Hebert, D.; Lindsay, M.P.; McIntyre, A.; Kirton, A.; Rumney, P.G.; Bagg, S.; Bayley, M.; Dowlatshahi, D.; Dukelow, S.; Garnhum, M.; et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: Stroke rehabilitation practice guidelines, update 2015. Int. J. Stroke Off. J. Int. Stroke Soc. 2016, 11, 459–484.

- Sakanaka, M.; Wen, T.C.; Matsuda, S.; Masuda, S.; Morishita, E.; Nagao, M.; Sasaki, R. In vivo evidence that erythropoietin protects neurons from ischemic damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 4635–4640.

- Wagenaar, N.; de Theije, C.G.M.; de Vries, L.S.; Groenendaal, F.; Benders, M.J.N.L.; Nijboer, C.H.A. Promoting neuroregeneration after perinatal arterial ischemic stroke: Neurotrophic factors and mesenchymal stem cells. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 83, 372–384.

- Kim, E.S.; Ahn, S.Y.; Im, G.H.; Sung, D.K.; Park, Y.R.; Choi, S.H.; Choi, S.J.; Chang, Y.S.; Oh, W.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation attenuates severe brain injury by permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in newborn rats. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 72, 277–284.

- Elmahdy, H.; El-Mashad, A.; El-Bahrawy, H.; El-Gohary, T.; El-Barbary, A.; Aly, H. Human Recombinant Erythropoietin in Asphyxia Neonatorum: Pilot Trial. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e1135–e1142.

- Wu, Y.; Bauer, L.; Ballard, R.; Ferriero, D.; Glidden, D.; Mayock, D.; Chang, T.; Durand, D.; Song, D.; Bonifacio, S.; et al. Erythropoietin for Neuroprotection in Neonatal Encephalopathy: Safety and Pharmacokinetics. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 683–691.

- Benders, M.J.; Van Der Aa, N.E.; Roks, M.; Van Straaten, H.L.; Isgum, I.; Viergever, M.A.; Groenendaal, F.; De Vries, L.S.; Bel, F. Van Feasibility and Safety of Erythropoietin for Neuroprotection after Perinatal Arterial Ischemic Stroke. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 481–486.e2.

- Andropoulos, D.; Brady, K.; Easley, R.; Dickerson, H.; Voigt, R.; Shekerdemian, L.; Meador, M.; Eisenman, C.; Hunter, J.; Turcich, M.; et al. Erythropoietin Neuroprotection in Neonatal Cardiac Surgery: A Phase I/II Safety and Efficacy Trial. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013, 146, 124–131.

- Gonzalez, F.; McQuillen, P.; Mu, D.; Chang, Y.; Wendland, M.; Vexler, Z.; Ferriero, D. Erythropoietin Enhances Long-Term Neuroprotection and Neurogenesis in Neonatal Stroke. Neuroscience 2007, 29, 321–330.

- Keogh, C.; Yu, S.; Wei, L. The Effect of Recombinant Human Erythropoietin on Neurovasculature Repair after Focal Ischemic Stroke in Neonatal Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 322, 521–528.

- Atallah, J.; Joffe, A.; Robertson, C.; Leonard, N.; Blakley, P.; Nettel-Aguirre, A.; Sauve, R.; Ross, D.; Rebeyka, I.; Western Canadian Complex Pediatric Therapies Project Follow-Up Group. Two-year general and neurodevelopmental outcome after neonatal complex cardiac surgery in patients with deletion 22q11.2: A comparative study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 134, 772–779.

- Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P. Neuroprotection of the preterm brain. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 162, 315–328.

More