There is a causal relationship between existential dangers to our biosphere and uour unsustainable consumption practices. AFor more than three decades, academics and researchers have explored ideas to make consumption practices sustainable. Still, a practical and widely accepted solution to the problem is missing. Sustainable consumption research has proliferated since 2015, indicating a heightened interest in the field. There are four major schools of thought in sustainable consumption research, employing three interdependent micro, meso, and macro levels of analysis to understand consumption practices. One innovative way to make consumption sustainable is consuming mindfully, a method that, along with sustainability, promotes subjective well-being, pro-sociality, and greater connectedness to nature, and decreases materialistic values. Temperance in consumption, resulting from a mindful attitude, connects self-care with societal and ecological care and adds to the consumer’s subjective well-being or quality of life, showing a direct relationship between sustainable behaviors and quality of life (QOL).

- sustainable consumption

- integrative review

- quality of life

- mindful consumption

- bibliometric review

1. Introduction

Introduction

As consumption is “the sole end and purpose of all production” [1] (p. 625), its exponential growth has created ever-growing production systems that exploit and deplete natural resources, to the point where, today, humanity is facing an existential crisis related to global warming and climate change [2]. This exponential consumption rise must be decelerated and made sustainable before it breaks the biosphere’s natural balance [3] and damages the life system [4] (p. 20) but the typical approach of putting into place efficient production systems alone [5], without making consumption sustainable, will not avert this looming danger. The Oslo Symposium defined sustainable consumption as “the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimizing the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardize the needs of future generations” [6]. Being both analytical and transformational [7], sustainable consumption research aims to build positive environmental attitudes and values and to transform those attitudes and values into appropriate behaviors [8–12]. Although three decades of sustainable consumption research (SCR) has seen many innovative ideas presented by diverse disciplines, due to missing practical strategies, little has been achieved in terms of consumption sustainability [13]; on the contrary, the consumption has accelerated, as indicated by the Earth Overshoot Day [14], indicating worsening situations and necessitating new innovative methods [13,15].

Academics from varied disciplines, including environmental economics [16,17], social psychologists [18,19], sociologists [20,21], and marketing [22] have analyzed consumption practices and proposed transformational measures to make them more sustainable [23,24]. These contributions to SCR from various disciplines have developed it into a diverse and fragmented field [25] composed of many overlapping, interdependent concepts and solutions with varying strengths and weaknesses [26,27]. Thus, reviews of this diverse literature can play a key role by consolidating advances in SCR and contributions to theory, policy, and practice.

Liu et al. [25] conducted a bibliometric review of SCR, based on documents published between 1995 and 2014. Their review examined the scope and composition of the SCR knowledge base, its development, and evolutionary turns. The review analyzed 920 publications and found that SCR had grown from a single-interest, focused discipline into a systematic one covering a wide range of diverse topics. Consumer behavior, environmental impact, and motivating consumers toward sustainable consumption were the prominent research themes. Since 2015, journal articles and reviews on sustainable consumption have doubled, expanding and modifying the research knowledge base, necessitating a new and updated analysis. Similarly, Corsini et al. (2019) performed a bibliometrics review [28] of SCR, analyzing publications that use practice theories as the main theoretical framework. They found that SCR was becoming a dominant topic for academics investigating social practice theories, and highlighted trends since 2009. The review recommended social practice theories as an effective tool for understanding consumption behaviors, especially in the emerging fields associated with the circular and sharing economy and smart cities.

As an academic discipline, business process, or management philosophy, marketing always focuses on the needs and wants of customers [29] to satisfy individual and organizational objectives [30]. Since its inception as an application of economics [31], marketing was designed to create demand and satisfy those demands for constant economic growth [32]. Thus, marketing is blamed as being a “consumption engineer” [32], promoting consumption-based well-being and happiness [33], and a proponent of materialistic values [34,35] and compulsive buying [36,37]. The aforementioned are all antecedents to unsustainable consumption behaviors [38], showing marketing’s “inherent drive toward unsustainability” (p. 45, [39,40]).

As digital technologies have taken over most marketing functions [41,42], to survive and be relevant, marketing needs to reevaluate its fundamental precepts and reorient itself to building sustainable societies [41]. With the evolution of marketing itself [43,44], things have been changing as the sustainability of consumption is gaining prominence in the marketing literature [45,46], proposing transformative conceptual and managerial solutions [47,48]. However, as Lunde [49] pointed out, the marketing approach to sustainability lacks conceptual framing and theoretical clarity, resulting in unreliable approaches and even generating terms like “greenwashing” [50] or “the dark side of corporate social responsibility” [51], contributing to the general mistrust of marketing. Therefore, marketing needs to break new ground for conceptually sound solutions that can add to the SCR toward changing the consumption culture to make consumption sustainable [52].

One innovative way to make consumption sustainable is consuming mindfully [53–56], a method that, along with sustainability, promotes subjective well-being, pro-sociality, and greater connectedness to nature, and decreases materialistic values [57]. Fischer et al. [10] concluded that mindfulness is an innovative, powerful tool fostering pro-social behavior and disrupting unsustainable routines; they highly recommend including mindfulness in future SCR. Temperance in consumption, resulting from a mindful attitude, connects self-care with societal and ecological care [54] and adds to the consumer’s subjective well-being or quality of life, showing a direct relationship between sustainable behaviors and quality of life (QOL) [58].

By taking methodological inspiration from previous research and updating and extending their findings [10,25,27,28], this study takes a holistic review of the sustainable consumption literature using bibliometric analysis [59] and integrative review methods [60,61]. The review section will then present a categorization of the literature using three interdependent levels of analysis (micro, meso, and macro) applied by researchers to understand consumption behaviors. Using the three-level structure and their interdependencies and focusing on individual consumption behaviors, a consumer-centric research area based on the quality of life and mindfulness will be proposed for future marketing practice, to explore future consumption sustainability research in the changing paradigm [41,62]. By fostering a mindfulness mindset in consumers to enhance their QOL, marketing can make consumers enablers of sustainability without making them responsible for it. The following research questions will be addressed in this review:

RQ1: What are the main features of the SCR literature, how has it evolved, and what are the conceptual similarities between its main features?

RQ2: What are the different levels of analysis applied by scholars in SCR? The literature has explored what should be considered individual sustainable consumption behaviors; is there any conceptual connectivity between them?

RQ3: What are the possible future research areas that marketing can explore within SCR to motivate individual consumers to consume more sustainably?

The review sourced SCR documents from the Scopus database using a search string composed by analyzing past reviews. These documents were analyzed with bibliometric tools [59] to answer RQ1, and a three-layer framework for the integrative review was composed using the results of the analysis. The framework was used to study the different levels applied by academics to developing SCR, highlighting their main features, strengths, and weaknesses [60,63] and to answer RQ2. Using the integrative review results, a mindfulness mindset-based sustainable consumption model was proposed, reframing sustainable consumption as a means of enhancing consumer life quality. For RQ3, marketing’s future role in SCR was discussed in the last section, with recommendations for its role in SCR development.

Discussion

The SCR literature shows the centrality of individual consumers in the proposed solutions and positions individual consumers as change actors, bringing significant change toward sustainability [22,70]. However, this argument relies on a few assumptions. The first assumption is that individual consumers can change consumption behaviors and consumption structures. Secondly, it is assumed that the individual consumer wants to change their consumption behaviors. Lastly, it is assumed that individual consumers want to be responsible for societal and ecological sustainability [332,333].

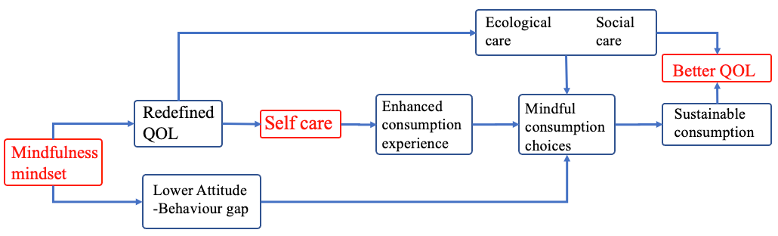

How can an individual consumer be motivated to consume sustainably? How can we develop intrinsic attitudes that make an individual consumer feel responsible for societal and ecological sustainability and be willing to be transformed into a sustainable consumer? How can consumers be empowered so that they do not feel powerless in adopting consumption sustainability? Most sustainability interventions make consumer transformative behavior an individual’s responsibility, possibly resulting in consumer resistance [152,334]. By building on the proposition made in the micro-level analysis, this review recommends mindful consumption for consumption sustainability. The recommendation repositions consumption sustainability as a path to a better quality of life [335], with consumers assuming responsibility for their QOL [336] where the aspiration for better QOL will motivate consumers to consume sustainably (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mindfulness-based sustainable consumption model for a better quality of life for the consumer (based on Sheth et al. [54] mindful consumption model).

The model (Figure 1) shows how a mindfulness mindset can lead to enhanced QOL through sustainable consumption, with redefined standards of QOL and “self-care”, attaching “self-care” to ecological and social care and enhanced awareness for the well-being of the natural and social environments and a moderated attitude to the behavior gap [10]. The mindfulness mindset reforms the standards of QOL to a new form of “self-care” that is tied up with social and ecological well-being. The new “self-care”, with enhanced socio-ecological care and awareness, will encourage mindful consumption choices, leading to consumption sustainability [54]. Many of the WHOQOL [335] facets are related to the natural and social environment that we live in, and their well-being directly relates to our QOL betterment (see Appendix D). The new, mindful “self-care” will strive for the well-being of these environments, resulting in an improved QOL. Mindfulness mindsets offset habitual, impulsive, and compulsive behaviors through improved self-control, ameliorating the conversion of any sustainable consumption intentions to behaviors [228, 337].

By reorienting consumption sustainability as a means for better QOL, this review “removes” consumer responsibility from the consumption sustainability paradigm (Figure 1). Consumers are required and empowered to strive for their own QOL betterment. Attaching environmental and social care and enhancing individual life quality, the model aims to make socio-ecological improvement part of self-care. Self-care is based on a redefined QOL, skewed toward improving non-financial aspects of quality of life for better health, more profound social and ecological values, and working within the need for financial stability. The model is in line with weak sustainable change [15,22,49], working to change the consumption system from within the system.

The answer to RQ3 in terms of the possible research areas that marketing can explore for bringing about consumption sustainability will be based on the proposed sustainable consumption model (Figure 1) through a mindful mindset and behavior. To foster, nourish and encourage the mindful mindset and behaviors for sustainable consumption, the research needs to involve all three levels (micro, meso, and macro) and their interdependencies (Figure 1). However, the first step is marketing’s restructuring itself from just a demand growth discipline, moving away from short-term sales targets to become an advocate of societal and ecological sustainability for consumer QOL betterment [42].

Marketing, a meso-level entity, evolves according to its contextual factors to create value through the anticipation and satisfaction of consumer demand [42]. Marketing’s emphasis on demand creation has contributed to making materialistic consumerism a dominant force in our DSP [22,148,338]. With the displacement of marketing by digital technologies, scholars have called for marketing to refine its identity and to learn and adopt the ideas from multiple disciplines for collaborative research and development [41,42,57]. Marketing is urged to reposition itself from a growth generator of material consumption to an advocate of a non-materialistic-based QOL for individual, societal and ecological betterment [57,339]. Therefore, the first step in future contributions of marketing toward consumption sustainability will be conducting research on reorientating marketing itself. Social and sustainability marketing and transformative consumer marketing have to take a central stage inside the marketing paradigm and dominate marketing thinking (in both academics and practitioners). Future research in marketing must use all the knowledge accumulated in the past 100 years of demand creation toward demand redirection, by connecting individualism to collective well-being, replacing material goods with human connections, and converting mindlessness to mindfulness for qualitative consumption growth. Similarly, marketing communication, new product development, and digital marketing tools, mainly social media marketing, have to be reoriented to raise awareness and adopt a non-materialistic QOL.

The proposed sustainable consumption model (Figure 1) is a bottom-up model emphasizing changing individual mindsets and behaviors. Therefore, on the micro-level, future marketing research must focus on discovering ways to foster mindful mindsets within individual consumers, to make them more connected to their social and natural environment. By using personal well-being as a motivator and developing a feeling of care for ecology and society, marketing can engender endogenous sustainability values and empower consumers to be enablers of sustainability, countering any of the dark side of consumption (e.g., materialism and compulsive buying).

Mindfulness interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in fostering self-esteem and self-regulation in children [340]; both these traits can help mitigate materialistic values and mindsets [34,341]. Educational programs incorporating such interventions for children can shape their values and behaviors, encouraging them to become mindful consumers [342,343] and making them change agents for socio-ecological sustainability [344]. Using sustainable consumption communication [15] and social media influencers [345] to spread the concept more widely, marketing can popularize mindful consumption [54], reducing materialistic traits and leading to improved well-being and life satisfaction among citizens [341]. By empirically exploring methods that propagate mindfulness-based sustainability values on the micro level, marketing research can build a mindful society of mindful individuals who are conscious of their negative consumption impacts [161], finding non-materialistic avenues for QOL improvement.

A mindful society needs sustainable products and services to support and facilitate a mindful and sustainable lifestyle. Future product development by marketing warrants that sustainable products should come with minimum or no extra cost, whether financial or otherwise. Service-dominant logic [346,347] emphasizes service and resource integration for value co-creation and promises a sound theoretical base for marketing to develop sustainable solutions. On the meso level, future sustainable marketing communication needs to promote lifestyles based on deeper human connections rather than hedonic consumption practices to achieve a society of mindful individuals. A mindful marketing practitioner, for example, can enable circular consumption [348,349] by developing new products that are easy to reuse and repair. Individuals with a mindfulness mindset form the social rules and regulations and develop social norms, resulting in social consumption practices [130,260,304,306] with a higher probability of having a sustainable structure.

Mindful individuals functioning within the sustainable consumption structures will have the capability to reform the macro institutions of culture, market, and governance. As the proposed model (Figure 1) has a bottom-up approach, marketing can advance sustainable values from micro to meso and macro levels by encouraging mindful consumers, reinforcing their sustainable values. Encouragement comes by developing methods to recognize the contribution made by mindful consumers to socio-ecological sustainability and project them as role models. Reinforcement requires developing more solutions that help in mindful consumption choices and supporting mindful social practices. This is a time-consuming but proven way for marketing to alter customs, values, and traditions on a societal level to change the consumption culture.

Macro-level market research for consumption sustainability in the future needs to investigate how the political and policymaking entities can be mobilized to promote mindful and sustainable consumption practices, as a challenge to the DSP [148]. The DSP is the result of three centuries of economic and political policies and cultural practices, and disrupting it will be a slow process. Therefore, marketing must find the most optimal techniques that can disrupt these practices from within the system. Politicizing the sustainability issue [22] can be an effective strategy for discussing sustainability on political forums, thus involving more consumer segments. Promoting mindful and sustainable lifestyles using social media can create opinions and generate dialog on a national, regional, and community level and may generate organic ideas of adopting mindful lifestyles for sustainability. Thus, on the macro level, marketing can act as a catalyst for sustainable lifestyle adoption by positioning itself as a dialog forum and promoting the example set by mindful individuals and their lives. To summarize, future marketing research for consumption sustainability should:

- Refine marketing fundamentals toward societal well-being as their primary goal.

- Help consumers to redefine their QOL, educating and encouraging them to undertake mindful consumption practices.

- Arrange logistics that encourage and facilitate a mindful mindset by developing products and technologies and composing rules and regulations that foster, nourish and encourage mindful consumption.

- Facilitate the movement of the mindful mindset from the micro level to the meso level and, thence, to the macro level.

Practical Implications

For a better QOL, developing a mindfulness mindset on a societal scale and reframing sustainable consumption as a means of QOL enhancement is required. By reforming its fundamentals from an economic growth generator, marketing as an academic discipline and business process can use the model in Figure 1 for consumer QOL enhancement. Marketing academics can apply the model to creating educational content that trains young people to develop a mindfulness mindset and be aware of the factors that enhance consumer well-being. The model can provide a strategic basis for marketing practitioners to develop campaigns that motivate consumers to become active participants in their transformation process, enhancing their QOL by making them aware of the benefits of sustainable consumption. Policymakers can utilize this model to facilitate and cultivate a societal mindfulness mindset that incentivizes sustainable consumption for the betterment of consumer QOL.

Limitations

The bibliometric analysis was based on the Scopus database; therefore, any influential articles outside the reach of Scopus were missed. A review based on multiple databases may provide additional findings. Secondly, the bibliometrics methodology is based on citation analysis. Bibliometrics analysis assumes that any highly cited paper is useful, even if that paper is cited for the purpose of disputing claims or results [350]. The bibliometric analysis will be biased toward older articles and more senior authors [168] with a higher citation count, neglecting newly published articles. The descriptive analysis of SCR showed that most of the SCR articles (55%) had been published since 2017. Most papers need time to become recognized and receive citation counts. Most new articles do not significantly impact the bibliometric analysis, due to the low number of citations, adding to this review the limitations of missing innovative ideas from recent articles.

Conclusions

The review was conducted to find the future role of marketing in sustainable consumption research. The review employed a bibliometric technique to analyze the structure of sustainable consumption research literature. It identified four major schools of thought or clusters. The bibliometric analysis also revealed three different layers of scholarship: individual or micro level, social-organizational structural or meso level, and system or macro level; thus, categorizing the literature into three micro, meso, and macro contextual levels. Rather than using identified clusters from the bibliometric analysis for the integrative analysis, a method generally followed in bibliometric studies, this review used the three contextual layers as a framework for the integrative review levels of SCR literature to systematically analyze concepts, ideas, and phenomena.

The integrative review discussed the three layers of the literature to understand how researchers have looked at the consumption process, how it affects and is affected by contextual factors and the behaviors employed by consumers toward becoming sustainable. An integrative review proposed a mindful consumption model that can be used as an umbrella term to describe most of the sustainable consumption behaviors discussed in the SCR literature. The integrative review also showed how the three layers are interdependent; thus, any research on consumption sustainability must be holistic and consider all the micro, meso, and macro factors when proposing solutions, to make consumption sustainable.

The SCR literature shows a centrality of individual consumers in terms of the proposed solutions. This approach assumes that individual consumers can change their consumption behaviors and structures, individual consumers want to change their consumption behaviors, and individual consumers want to be responsible for societal and ecological sustainability. Nevertheless, this approach has produced very few changes in consumption practices and has deterred consumers from adopting sustainable consumption behaviors. Individual consumers need an intrinsic motivator that can substitute consumption experience for becoming sustainable. This review proposed a QOL betterment model, considering a mindfulness mindset as the motivator that inspires individuals to consume sustainably. Aspiration to a better QOL will motivate individual consumers at the micro level to be mindfully aware of their social and ecological environment and to connect their personal well-being to socio-ecological well-being and, as a result, to refine their consumption practices.

Marketing’s nature as a value creator can play the role of a change agent to increase the QOL of consumers and bring about socio-ecological sustainability. This can happen by fostering mindfulness mindsets, training consumers in mindful consumption practices, and providing them with an infrastructure to facilitate mindful consumption. Using the proposed model, this review recommends that marketing organizations should research methods of refining and readjusting their fundamental tenets to promote qualitative consumption, which can reform the consumer’s mindset regarding progress, based on pro-social and pro-ecological choices. The sustainable world requires a mindfulness mindset in all sections of society. Marketing researchers must find ways to foster mindful mindsets on the micro-level and, using a bottom-up approach, diffuse these non-materialistic mindfulness mindsets to the meso and macro levels of society for a holistic change regarding sustainability.

2. Micro

The micro-level SCR aims to change consumption practices from the demand side [59], where consumer demand will be the primary driver of sustainability [60]. There are two paths to changing demand-side consumption; consumption reduction (e.g., sufficiency) or consumption refinement (e.g., sharing), in line with Lorek and Fuchs [22][61] and their concept of strong and weak sustainable consumption. The weak approach achieves sustainability by refining the demand toward low-impact products and efficient production systems, whereas the strong sustainable consumption approach redefines the consumption systems toward lower demand to achieve sustainability.Responsible Consumption

Webster [62] defined the socially responsible consumer who “takes into account the public consequences of his or her private consumption” (p. 188) through efficient resource usage, due to a regard for the needs of the whole human race [63]. Roberts [64][65] categorized responsible consumption into societal and environmental dimensions, meaning that a socially responsible consumer will always consume products that have a minimal effect on the society and environment. A responsible consumer will always feel liable for the social and environmental consequences of consumption choices [66]. Responsible consumption is a broad concept [67][68] that comprises purchasing products with minimum societal or environmental impact, engaging with a specific company as a support for its philanthropic efforts, boycotting an unethical company or product [69], willingly trading off quality, prestige, or convenience for an extra cost or lower performance [70]. Responsible consumption covers green and ethical consumption; green consumption is more concerned with the environmental impact of consumption [71], whereas ethical consumers care about consumption’s moral consequences.Green Consumption

Green consumption means to choose products causing minimum ecological impact, moderate their consumption, be more conscious of the produced waste, engage with companies making the minimum environmental impact, recycle frequently, and opt for clean or renewable energy. Green consumers are willing to bear the extra cost and effort of green consumption by refining their consumption practices if it contributes to environmental sustainability while maintaining their current lifestyle [72][73]. The emphasis of green consumption is more on ecological sustainability than social sustainability [74], and uses consumption as a means of identity creation [75]. As green products and services are just another market offer, they are criticized for perpetuating consumption rather than inhibiting it [76][77] to sell more products [78]. Green products are also blamed for giving consumers a false belief that they are being pro-sustainability by spending more [66], failing to challenge the dominant social paradigm (DSP) [79].Ethical Consumption

There is a clear distinction between the ethics of consumption and ethical consumption. The ethics of consumption question the morality of modern consumerism to challenge it, whereas ethical consumption uses consumerism by expressing moral commitments [66][80]. Klein, Smith, and John [81] described ethical consumption as being “against selfish interests for the good of others,” where consumption is used as a means for social good (p. 93). Ethical consumptions are norms-driven [82] and depend on socioeconomic factors (for comparing scales, see Roberts [64] and Yan and She [68]), which is why ethical consumption decisions are based on moral standards (in the individual or the group) that guide consumption behaviors [83] (p. 113). Ethical consumption is not always sustainable as it can be motivated by diverse factors like human rights, the environment, fair trade, and political orientations [84]. Ethical consumption movements like Fairtrade and “buy local” can encourage overconsumption to help the producers; they are, thus, criticized for not contributing to sustainable consumption [85][86].Anti-Consumption

Anti-consumption intentionally and meaningfully avoids consumption by rejecting or refusing material goods acquisition or by reusing once-acquired goods. Anti-consumption is a financially independent and intentional nonconsumption behavior, manifested through practices like frugality and voluntary simplicity, creating a “resistance” identity [87]. Frugality is the action of restricting acquisition voluntarily, with the resourceful usage and thoughtful disposal of economic goods to avoid waste and save material resources [88][89], making it a monetary-based anti-consumption behavior with few environmental concerns [88][90]. For a frugal person, saving material resources and reducing waste is virtuous [91] and a source of pleasure [92]. Due to its highly materialistic nature, frugality can have a negative correlation with green consumption [93] and is yet to develop as a real anti-consumerism phenomenon [94]. Voluntary simplicity [94] is a non-monetary-motivated anti-consumption activity wherein the primary goal is a good life based on non-material consumption [95][96]. Voluntary simplifiers are economically stable but are not frugal [97][98]. Their satisfaction stems from the non-material values they cultivate to live soulful, conscious, simple, and “inwardly rich” lives for inner peace and psychological well-being [99]. Elgin and Mitchell [100] consider material simplicity, the desire for small human-scale institutions, self-determination, ecological awareness, and personal/inner growth as the five core values of voluntary simplicity.Mindful Consumption

Mindfulness implies an awareness of [101] or an enhanced focus on experiences, feelings, and thoughts, to be a conscious part of everyday mundane activities [102] like eating food or interacting with family or friends [103]. Mindfulness encourages more pro-environmental behavior by inducing benevolent attitudes and compassion toward others and by inhibiting materialistic hedonic values [104][105]. Mindfulness promotes subjective well-being, a sustainability behavior pre-condition, and positively moderates intentions into actual behaviors [106][107]. The advantage of mindfulness is that it can be cultivated [108][109] for ecological well-being on an individual and societal level [110][111]. There is no clear operationalized definition of mindfulness [112], resulting in a fragmented and weak objective observation that is missing the robust and empirically proven causal effects of mindfulness on sustainable consumption [55]. Sheth et al.’s model, mindful consumption is viewed as the link between a person’s mindset and behaviour (see Sheth et al. [54] for a detailed description of the mindful consumption model). It affects how one cares about themselves, the community, and the environment and any subsequent consumption behaviours (repetitive, acquisitive, aspirational). The two-part model unites mindfulness’s awareness and caring with its temperance part [113] to propose customer-centric “mindfulness consumption”. Sheth et al. [54] want sustainability efforts to be (1) more customer-centric, (2) holistic, (3) targeting the mindset as well as behaviour, and (4) making consumers, businesses, and policymakers all responsible for sustainability. There are two parts to the mindful consumption model. The “mind” part connects self-well-being with community and nature well-being [110] for mindful resource extraction and waste disposal. Consumption temperance [113] involves acquiring goods and services within the bounds of needs and capacity [114], breaking the recursive shopping cycle for new fashion or technology [115], and being non-conspicuous about consumption [116]. Mindfulness can potentially change compulsive, impulsive, habitual, and addictive consumption behaviors [117]. Empirical data on the causal effects of mindfulness consumption are missing [55], highlighting the research gap. By empirically testing mindfulness consumption models like the one in [54], practical and objective steps toward sustainability of consumption can be recommended.Sharing

As one of the three ways to acquire goods [118], sharing is a non-reciprocal and social act of giving to others that which is ours for their use and getting from others things for use [119]. For Belk, the non-reciprocal dimension of sharing is essential as it gives joint ownership [118], creating an extended self that is connected to those [120]. He explains the benefits of sharing via the examples of mothering and “share-consuming” resources within a household, a behavior that creates bonds and connections and breaks interpersonal barriers, contributing to wellbeing. Sharing activities also include a picnic with others at a beach or a park, using public infrastructure, e.g., roads and streetlights, sharing advice, jokes, opinions, photos, and comments, and voluntary social work [118]. Sharing a meal, a car, or communal laundry all bring about sustainability by decreasing resource usage and waste while enhancing personal wellbeing [118]. This quality has evolved the idea of sharing from an individual- and family-level concept [121] into meso- and macro-level phenomena of collaborative consumption [122] for collaborative, access-based consumption [123] and a sharing economy [124]. As a solution to the problems of unsustainable consumption, both the sufficiency economy and the sharing economy have recently garnered much academic and managerial interest, as indicated by the increase in the volume of research articles.Sufficiency

Fuchs and Lorek [125] defined sufficiency as “changes in consumption patterns and reductions in consumption levels” (p. 262). Sufficiency is the reconfiguring of consumption practices by consuming material goods for an extended period, decreasing demand levels, keeping conspicuous consumption at a minimum [126], enjoying nonmaterial experiences, and developing an “enoughness” mindset and behavioral shift. The “sufficiency turn” of SCR [24] can be considered SCR’s third evolutionary phase at the individual level, although it also moves sustainability toward the societal level to challenge the DSP [127]. Sufficiency can be on an individual, community, or societal level.The Mindful Mindset for All Sustainable Consumption Behaviors

Mindful consumption is to be conscious of consumption’s socio-ecological impact and to minimize it [128]. This consciousness comes from a mindset that is manifested by behaviors intended to minimize the impact. A socially responsible consumer will consider the consequences of their consumption [62], whereas ethical consumers aspire to achieve some social good from their consumption activities [81]. Therefore, the ethical and responsible consumer will always think and be aware of consumption activity’s socio-ecological impacts. This pro-ecological and pro-social consciousness results from the mindset possessed by an ethical or responsible consumer that targets minimal or no effects of consumption on socio-ecological well-being. The micro-level SCR aims to change consumption practices through their reduction or refinement [59]. Green consumption and sufficiency consumption refines consumption activities in the direction of sustainability by lower resource usage and lower subsequent waste generation. Anti-consumption [129] and voluntary simplicity [95] avoid consumption by rejecting or refusing material goods, whereas opting for non-material consumption by sharing [118] results in lower resource usage. Using the fundamentals of mindfulness, Sheth et al. [54] proposed a model that aims for sustainability by targeting the mindset and behavior of the consumer. The “mind” or awareness part of the concept connects the individual’s well-being with the well-being of the community and nature [111], resulting in ethical or responsible mindsets that are aware of the consumption consequences. Sheth et al.’s [54] model includes a “temperance” section that requires consumption only to meet needs and discourages repetitive and hedonic consumption to moderate consumption. Green, sufficiency, sharing, anti-consumption, and voluntary simplicity modify consumption behaviors toward moderation and decrease their socio-ecological impact. In line with Lim [130], all sustainable consumption awareness and behaviors result from a mindful mindset. Therefore, mindful consumption can be an umbrella term covering all micro-level sustainable consumption behaviors. A consumer with a mindfulness mindset will be a responsible and ethical consumer. Consumers with responsible and ethical mindsets will temper (reduce or refine) their consumption through sufficiency, voluntary simplicity, anti-consumption, green consumption, and sharing behaviors, to become sustainable consumers. Therefore, mindful consumption can be used as an umbrella term, covering all the micro-level sustainable consumption mindsets and behaviors discussed in the analysis of micro-level SCR.3. Meso

“We need research that helps us better understand the factors that encourage and/or hinder companies from focusing on environment and sustainability in their marketing and advertising campaigns” [77] (p. 694). The micro-level analysis focuses on the individuals, whereas on the meso-level, it analyzes the “interdependencies of individual system elements” [131]. Meso-level intermediaries connect micro-level individuals to the macro governing entities in society [132]. Cultural, economic, and political macro-level systems create rules and procedures for society. Meso-level entities are the social-organizational [133] arrangements that give an applied structure to those macro-level guidelines, resulting in these entities shaping social norms and behavioral patterns. Private or public organizations that implement those rules through products and services, the communities that engage with those organizations, and the social norms, practices, and symbols that objectify the rules are all meso-level entities. Researchers look at two meso-level entities—business organizations and consumption social practices—to achieve an overview of how meso-level behaviors can contribute to the “greening” of consumption [134]. A one-liter bottle of drinking water will cost almost four liters of water to produce [135]. Therefore, understanding those factors that encourage or inhibit meso-level entities from focusing on environment sustainability [136] is vital, as most of the ecological impacts of consumption happen “before” start consuming. Consumption’s environmental impact is only one-third of the total impact [137]; two-thirds of it is from the manufacturing process and the logistics of shipping consumer goods. Secondly, consumption behaviors are shaped by the solutions offered by businesses and social practices. Sustainability at the meso level will have a direct effect on both the micro and macro levels.Business Organizations

All business activities are organized to produce goods and services and deliver them to the consumer, through an intricate, interdependent system of producers, infrastructure, consumption practices, and the consumer, called the “system of provision” [138]. Analyzing and making the subsystems of provision more efficient can result in more sustainable consumption patterns [139]. Businesses exhibit social and ecological responsibility by innovating regarding cleaner production practices and by supporting consumers in becoming more responsible consumers, for example, by the marketing of green products [140] with proper product labels or eco-labeling, and through corporate social responsibility (CSR) [141]. Eco-labeling effectively communicates sustainable consumption policies to the market and provides consumers with a primary informative tool to assess whether a product is green and meets specific environmental standards [142]. However, there are limitations to the effectiveness of labels in nudging customers toward more sustainable choices. Eco-labels are noticed mainly by the green consumers who are already ecologically conscious and are adopters of green products [143]. Eco-labels are unable to deliver credible information. In addition, if eco-labeled products do not come with economic value, they are highly likely to be rejected. Ecolabeling is one of the diverse ways that corporations show and promote their environmental commitment and social responsibility or CSR to the consumers. CSR, which became part of corporate strategy in the 1990s [137], has multiple dimensions [144], including promoting sustainable consumption behaviors. With its emphasis on sustainability, CSR philanthropic activities promote altruistic behavior that cares about ecology and society. Secondly, by becoming a model of sustainable behavior to its employees [145] and customers [146], corporations induce sustainable practices. As corporations connect CSR with their profits, they become efficient users of natural resources; therefore, they have less environmentally harmful practices, transforming them into good corporate citizens [147]. One of the most common criticisms of CSR is “greenwashing”, a practice as old as the “green movement” itself [50] wherein a company presents itself or its products as environmentally friendly without providing reliable information to back this claim [148][149]. Using “green” as a promotional tactic decreases the trustworthiness of the cause, and other companies genuinely engaging in green business practices also lose consumers’ trust. Another criticism of CSR is regarding the relationship of CEO personality with CSR. There is a positive correlation between a CEO’s need for attention and CSR initiatives [150]. Due to their egoistic personalities, CEOs tend to opt more for externally oriented CSR activities [151] that can feed their personal need for attention and image-building [150], resulting in CSR activities that do not generate the benefits discussed above and lead to lower consumer trust in CSR. Businesses always try to efficiently use raw materials in their production processes as this is directly connected to their production cost. With the idea of reduction, reuse, recovery, and recycling in the circular economy , businesses try to create value from waste, converting from linear to circular resource consumption and saving natural recourses. The idea of the circular economy is strongly associated with economic prosperity and making businesses more efficient, followed by environmental concerns. This is mainly due to the circular economy’s business-production characteristics, like remanufacture and reuse, which aim for efficient manufacturing. Efficient resource usage makes the circular economy a sustainable business practice. The circular economy has the potential to bring about “transformational improvements” in sustainable consumption practices. The efficient use of resources, an emphasis on recycling [152], the reuse of spent resources, and the repurposing of underused recourses all result in lower energy consumption and emissions by production processes [153]. The circular economy, over time, has encompassed many overlapping concepts with subtle identities [154]. The sharing economy is a free or for-profit peer-to-peer exchange of underused assets, e.g., Airbnb. The collaborative economy or collaborative consumption is an online exchange system, matching buyers and sellers, e.g., eBay [155], while others, e.g., Uber, are platform-based businesses providing on-demand services [156]. The circular economy is not directed toward lowering consumption or the sufficiency of consumption. Instead, it aims to make value-creation green or responsible by emphasizing efficient exchange and resource usage. This is why nearly 85% of the circular economy is aimed at economic prosperity and environmental quality, without enough societal impact. With its dependence on online and social commerce platforms enabling peer-to-peer exchange, a circular economy can potentially encourage hedonic and conspicuous consumption [18] and is criticized as a new form of the old consumption system. For this reason, both the circular economy and CSR are deemed insufficient to bring about real change regarding environmental and societal sustainability.Theory of Social Practices

Consumer behavior research relies on the consumer’s behavior, values, attitudes, and perceptions to understand and conceptualize decision-making. The consumer agency of decision-making is the main target of SCR, dominating academic research and policy development [28]. These analyses either position the consumer as a rational utility maximizer, a meaning-creating being, or a rule-following actor functioning inside physical, psychological, and cultural boundary factors. Humans confront the boundary factors of challenging situations by forming social practices, using their rationality, motivations, and perceptions [28]. By analyzing these practices, the motivations and perceptions of the individuals can be found, along with the social norms that guided their synthesis and evolution [28]. The origins of the multiple theories of practices go back to the writings of Marx, who called them “praxis”: the relationship between these praxes or practices and recursive individual acts forms and reforms social structures. The individual has agency but is bounded and is rational and impulsive in these dynamic and constantly changing practices. Practices have a heuristic nature, due to their routinized, sequential, “doing over thinking and material over symbolic” characteristics in creating meaning [157]. Using practices as the unit of analysis rather than treating them as individual practices shifts the focus from individualistic behavior to the way people evolve into performing certain behaviors. Shove [158] used the concept of laundry to explain how the contextual factors of technology have transformed laundry from the practice of washing clothes to a supply system of crisp, nice-smelling, “fresh” clothing. This has resulted in households doing more laundry and doubling their laundry energy requirements, losing the gains provided by efficient washing machines to a “rebound effect”, due to evolution in the practice of laundry. As practices are decided by social, technological, cultural, and governance forces [158], “a combined focus on the technological and cultural dimensions of innovation in consumption practices” [159] (p. 821) will bring about the desired sustainability. Most of the consumptions [160] and have an invisible impact [161] that can only be controlled or decreased by changing the practices governing those practices. However, Warde [157] points out that theories regarding practices cannot comprehensively analyze the macro-level aspects of consumption. Evans states that due to their partial analysis and lack of understanding of market dynamics, theories of practice fall short of fully understanding consumption, failing to present a complete solution for the sustainability of consumption. Making the consumer solely a follower of practice who does not have any agency is another gap where practice theories do not fully grasp individual adaption and experimentation processes [162].4. Macro

Political, economic, social and cultural, technological, and environmental factors are the macro socio-cultural factors that direct the social world’s development and norms [163]. These factors created the present consumption-based dominant social paradigm (DSP) [79] that has shaped lives over the past three centuries. Although economists developed DSP, it was propelled by politicians, who saw it as a sure route to political success. Businesses and marketers projected this DSP and made consumption the only means of identity creation and prosperity. The quality of lives revolves around the idea of material possessions, wherein possessing material goods decides power, authority, respect, social status, and income levels, with little or no regard for social and environmental development. A macro-level SCR aims to analyze and understand the social systems forming the structural institutions guiding people’s lives, and proposes an alternative socio-economic system that “will be ecologically and socially literate, ending the folly of separating economy from society and environment”(p. 77). This new socio-economic system will provide an updated DSP of new standards of wealth and well-being, with an emphasis on ethics in economic life, transforming consumption only for the satisfaction of “real need” [164]. Prosperity will be based on degrowth, judged according to social capital, physical and spiritual health, and a better work-life balance. In this new DSP, science will build knowledge instead of just acting as a workshop for new production systems [79]. These production systems will continuously operate within the ecological thresholds. The new DSP aims to design, encourage and facilitate ecological behavior at micro- and meso levels [127] so that people can become ecological citizens [165]. Ecological citizens are defined as politically active consumers who, by their product choice, usage, and means of disposal, exert pressure on the economic system, propagate the political discussions on sustainability, and “become a change agent” promoting sustainable lifestyles. Morals decide the consumption decisions of ecological citizens, with prioritization of the collective good over that of the self [81], and a willingness to bear the extra cost or effort. The new socioeconomic structures will motivate, activate, and provide logistics to transform consumers into ecological citizens with sustainable consumption values, ideals, and lifestyles. The new DSP has its origins in a nearly century-old alternate economic system, where prosperity is achieved through non-growth means [163]. Jackson has explored this new economy in detail, defining the “new degrowth economic” model. Jackson’s idea of the new economy is to decouple it from resource usage growth and make it a regenerative economy. The new economy will have decreased work weeks for more sharing of work and will produce higher-quality products using more labor-intensive crafting, decoupling from the productivity mania, investing in material efficiency rather than material consumptions [166], developing areas like art, music and literature and spiritual well-being, in building public goods, and in knowledge creation. In the new economy, people will flourish through encouraging ethical, social, and sustainable enterprises, community banking, the circular economy, micro-financing, and peer-to-peer lending, and community energy generation. Thus, the degrowth economy will decouple growth from materialistic values and transform business and consumption practices into sustainability. Even though the idea of a degrowth economy is nearly a hundred years old, there has been no practical implementation of most of the proposed measures, the DSP is not challenged, and the proposed alternates have found no traction in business practices. Ethics or moral values have not replaced societal materialistic standards for judging prosperity and wellbeing. Of all the measures mentioned above for people’s prosperity, only the circular economy and its various forms have been adopted fully, due to their resource efficiency and ability to generate profit. The forces that have shaped the DSP still favor consumption in society, while macro-level projects require new ideas and political discourse. Maybe the solution lies in becoming “a political project with the community and personal and collective wellbeing at its heart” [50] (p. 169).Complete text, review findings and analysis can be viewed at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/7/3999/htm