Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Marcelo Ribeiro and Version 3 by Camila Xu.

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) has been largely used for thousands of years in traditional Chinese medicine. Licorice and its derived compounds possess antiallergic, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor effects. G is a triterpene glycoside complex and has been shown to possess cytotoxic effects against several cancer cell lines such as colon, lung, leukemia, melanoma, and glioblastoma (GBM). GA, an aglycone of G, has been demonstrated to have pro-apoptotic effects on human hepatoma, promyelocytic leukemia, stomach cancer, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-infected cells, and prostate cancer cells in vitro by inducing DNA fragmentation and oxidative stress.

- Glycyrrhiza glabra-derived compounds

- glycyrrhizin (G)

- glycyrrhetinic acid (GA)

1. Introduction

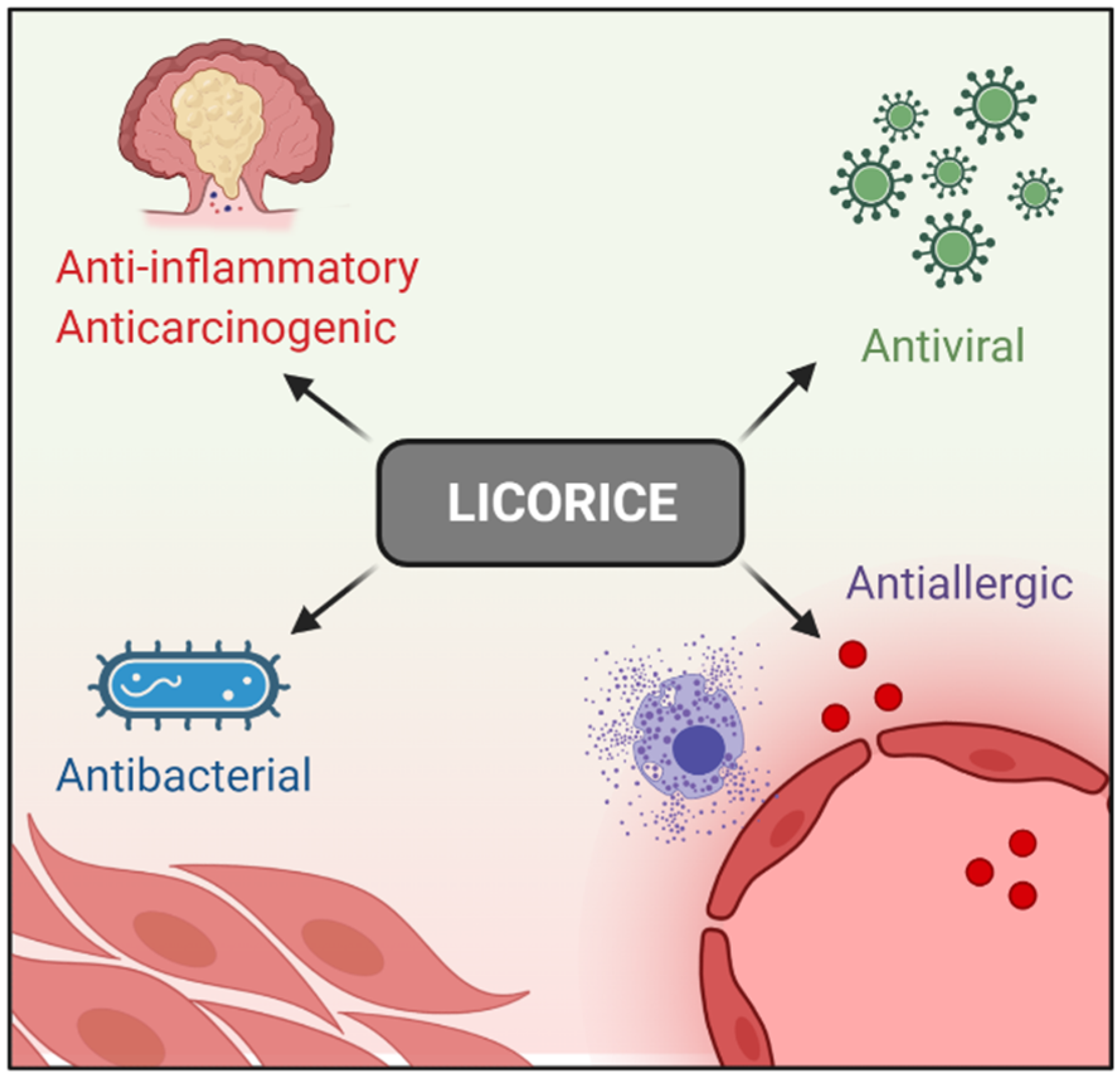

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years. Clinically, it is used widely to treat immune systems, respiratory, and digestive diseases [1][2][3][4][5][6], and no severe side effects have been reported so far [7]. In addition, Licorice-derived compounds possesses antiallergic, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic effects [8][9][10]. These pharmacological properties aid in inflammatory disease treatment [11][12][13] (

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years. Clinically, it is used widely to treat immune systems, respiratory, and digestive diseases [1,2,3,4,5,6], and no severe side effects have been reported so far [7]. In addition, Licorice-derived compounds possesses antiallergic, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic effects [8,9,10]. These pharmacological properties aid in inflammatory disease treatment [11,12,13] (

Figure 1

).

Figure 1. Licorice pharmacological properties.

Licorice pharmacological properties.

The main bioactive compounds isolated from Licorice are glycyrrhizin (G) and glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) [14]. G is a triterpene glycoside complex and has been shown to possess cytotoxic effects against several cancer cell lines such as colon, lung, leukemia, melanoma, and glioblastoma (GBM) [9][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]. Additionally, the incidence of liver carcinogenesis in patients with hepatitis C was clinically reduced after G administration [22]. GA, an aglycone of G, has been demonstrated to have pro-apoptotic effects on human hepatoma, promyelocytic leukemia, stomach cancer, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-infected cells, and prostate cancer cells in vitro by inducing DNA fragmentation and oxidative stress [23][24][25]. In addition, several genotoxic studies have indicated that G is neither teratogenic nor mutagenic and may possess anti-genotoxic properties under certain conditions [26][27]. As a result, there is a high level of use of Licorice and GZ in the US with an estimated consumption of 0.027–3.6 mg/kg/day [27].

The main bioactive compounds isolated from Licorice are glycyrrhizin (G) and glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) [14]. G is a triterpene glycoside complex and has been shown to possess cytotoxic effects against several cancer cell lines such as colon, lung, leukemia, melanoma, and glioblastoma (GBM) [9,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Additionally, the incidence of liver carcinogenesis in patients with hepatitis C was clinically reduced after G administration [22]. GA, an aglycone of G, has been demonstrated to have pro-apoptotic effects on human hepatoma, promyelocytic leukemia, stomach cancer, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-infected cells, and prostate cancer cells in vitro by inducing DNA fragmentation and oxidative stress [23,24,25]. In addition, several genotoxic studies have indicated that G is neither teratogenic nor mutagenic and may possess anti-genotoxic properties under certain conditions [26,27]. As a result, there is a high level of use of Licorice and GZ in the US with an estimated consumption of 0.027–3.6 mg/kg/day [27].

However, GA oral efficacy is impaired due to its low solubility and permeability through the gastrointestinal mucosa [28]. It has been shown that GA administered through nanocarriers (GA-F127/TPGS-MMs) [29], micellar carrier based on polyethylene glycol-derivatized GA (PEG-Fmoc-GA) [30], and microparticles [31] increase absorption significantly [28][29][30][31]. Both G and GA have been prescribed for several therapeutic purposes, such as cancer and inflammation; however, side effects have pointed out the problem of their toxicity [32].

However, GA oral efficacy is impaired due to its low solubility and permeability through the gastrointestinal mucosa [28]. It has been shown that GA administered through nanocarriers (GA-F127/TPGS-MMs) [29], micellar carrier based on polyethylene glycol-derivatized GA (PEG-Fmoc-GA) [30], and microparticles [31] increase absorption significantly [28,29,30,31]. Both G and GA have been prescribed for several therapeutic purposes, such as cancer and inflammation; however, side effects have pointed out the problem of their toxicity [32].

Dipotassium glycyrrhizinate (DPG), a dipotassium salt of GA, has been recently used as a flavoring and skin conditioning agent with demonstrated anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory properties [32]. It can inhibit leukotriene and reduce histamine levels with an apparent lack of adverse side effects [32][33][34]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that DPG has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, anti-ulcerative, and antitumoral properties [11][13][35].

Dipotassium glycyrrhizinate (DPG), a dipotassium salt of GA, has been recently used as a flavoring and skin conditioning agent with demonstrated anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory properties [32]. It can inhibit leukotriene and reduce histamine levels with an apparent lack of adverse side effects [32,33,34]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that DPG has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, anti-ulcerative, and antitumoral properties [11,13,35].

2. G, GA, and DPG-Mediated Anti-Inflammation Regulation

As stated previously, Licorice compounds such as G, GA, and DPG have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiviral, immunomodulatory, and antitumor properties [11][12][13]. Inflammation is an evolutionarily conserved, tightly regulated protective mechanism that comprehends immune, vascular, and cellular biochemical reactions. The normal inflammatory response is temporally restricted and, in general, beneficial to the host. Chronic inflammatory response, on the other hand, is a risk factor for the development of several diseases such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes mellitus, among others [36][37]. The anti-inflammatory effects of G and GA have long been reported. G has exerted anti-inflammatory actions by inhibiting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by neutrophils, the most potent inflammatory mediator at the site of inflammation [38]. Moreover, G has enhanced interleukin (IL)-10 production by liver dendritic cells in mice with hepatitis [39]. GA has presented anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogen effects on several tumor cell lines such as human hepatoma (HLE), promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60), stomach cancer (KATO III), and prostate cancer (LNCaP e DU-145) by both DNA fragmentation and gene deregulation required for oxidative stress control [23][24][25].3. G, GA, and DPG-Mediated Crosstalk between Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Pathways

Oxidative stress consists of an imbalance of endogenous pro-oxidant and antioxidant activities, characterized by excessive formation of high ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [40]. Small amounts of ROS are synthesized physiologically and act on cell homeostasis; however, in the disease context, the excessive synthesis of ROS disrupts the antioxidant defense system, causing cellular apoptosis [40]. This condition is commonly associated with oxidative changes such as lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, carbonyl adduct, nitration, and DNA impairment as well as the induction of inflammatory processes, leading to several diseases [41][42]. Cyclooxygenase type 2 (Cox-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) enzymes, responsible for the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, prostaglandin E2 (Pge-2), and nitric oxide (NO), play relevant roles in oxidative and acute inflammatory processes [42]. The high mobility group box 1 (Hmgb1) cytokine plays an important role in the pathologic process of endothelial permeability under oxidative stress [42]. DPG and G have presented antioxidant effects due to their negative modulation of Hmgb1 in the DSS-induced colitis mice model [42]. It has been shown that G inhibits Hmgb1-cytokine secretion by blocking the Cytochrome C release and caspase-3 activity, consequently inhibiting apoptosis in inflammation-related stroke rat models [43][44]. In addition, the G compound decreases the iNOS, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression levels by the modulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38-MAPK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (p-JNK) signaling pathways in brain vascular cells [44] and by preventing oxidative stress and apoptosis through the inhibition of p38-MAPK, p-JNK, and NF-κB signaling pathways in lung cells [45]. Accordingly, the G compound can inhibit oxidative stress and inflammatory response by attenuating the activity of the Hmgb1 and NF-κB signaling pathways, with decreased levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) in lung cells [46]. Moreover, G increases glutathione-S-transferase (GSTs) levels, decreases MDA, and negatively regulates the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) in liver cells [47]. G compound has been shown to suppress NF-κB pathway through inhibiting the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in renal cells [48] and reducing the formation of intracellular ROS. Moreover, an activation of the AMP/nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor-2 (NRF2) pathways in vitro was observed, positively regulating the antioxidant enzymes, HO-1, NQO-1, and GCLC and negatively regulating TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [49]. According to descriptions, GA also suppresses oxidative stress and neuroinflammation induced by A1C13 through TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway inhibition [50]. In accordance, one study has observed that GA was able to attenuate oxidative stress and neuroinflammation induced by rotenone reducing the activation of the ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule-1 (Iba-1), preventing glutathione depletion, lipid peroxidation inhibition, and attenuation of the induction of COX-2 and iNOS [51]. In addition, a restored mitochondrial complex I and IV, a reduction in the generation of ROS, the release of Cytochrome C, and ultimately cell apoptosis inhibition after exposure to GA in brain tissue of adult Sprague Dawley Rats were observed [52]. GA can suppresses lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis through activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, and inhibition of the NF-κB in renal cells [53]. GA also suppresses oxidative stress and inflammation through activation of the NRF-2 and HO-1 pathways and IκB and NF-κB p65 signaling inhibition in cardiac cells [54]. In the liver tissue of rats, GA inhibits NTiO2-induced apoptosis by superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activation [54]. Moreover, it has been shown that GA can inhibit caspase-3 and -9 at mitochondria in HepG2 cells, positively and negatively regulating Bcl-2 and Bax proteins expression, respectively [55] (2. G, GA, and DPG-Mediated Anti-Inflammation Regulation

As stated previously, Licorice compounds such as G, GA, and DPG have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiviral, immunomodulatory, and antitumor properties [11,12,13]. Inflammation is an evolutionarily conserved, tightly regulated protective mechanism that comprehends immune, vascular, and cellular biochemical reactions. The normal inflammatory response is temporally restricted and, in general, beneficial to the host. Chronic inflammatory response, on the other hand, is a risk factor for the development of several diseases such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes mellitus, among others [36,37].

The anti-inflammatory effects of G and GA have long been reported. G has exerted anti-inflammatory actions by inhibiting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by neutrophils, the most potent inflammatory mediator at the site of inflammation [38]. Moreover, G has enhanced interleukin (IL)-10 production by liver dendritic cells in mice with hepatitis [39]. GA has presented anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogen effects on several tumor cell lines such as human hepatoma (HLE), promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60), stomach cancer (KATO III), and prostate cancer (LNCaP e DU-145) by both DNA fragmentation and gene deregulation required for oxidative stress control [23,24,25].

3. G, GA, and DPG-Mediated Crosstalk between Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Pathways

Oxidative stress consists of an imbalance of endogenous pro-oxidant and antioxidant activities, characterized by excessive formation of high ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [47]. Small amounts of ROS are synthesized physiologically and act on cell homeostasis; however, in the disease context, the excessive synthesis of ROS disrupts the antioxidant defense system, causing cellular apoptosis [47]. This condition is commonly associated with oxidative changes such as lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, carbonyl adduct, nitration, and DNA impairment as well as the induction of inflammatory processes, leading to several diseases [48,49]. Cyclooxygenase type 2 (Cox-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) enzymes, responsible for the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, prostaglandin E2 (Pge-2), and nitric oxide (NO), play relevant roles in oxidative and acute inflammatory processes [49].

The high mobility group box 1 (Hmgb1) cytokine plays an important role in the pathologic process of endothelial permeability under oxidative stress [49]. DPG and G have presented antioxidant effects due to their negative modulation of Hmgb1 in the DSS-induced colitis mice model [49]. It has been shown that G inhibits Hmgb1-cytokine secretion by blocking the Cytochrome C release and caspase-3 activity, consequently inhibiting apoptosis in inflammation-related stroke rat models [50,51]. In addition, the G compound decreases the iNOS, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression levels by the modulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38-MAPK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (p-JNK) signaling pathways in brain vascular cells [51] and by preventing oxidative stress and apoptosis through the inhibition of p38-MAPK, p-JNK, and NF-κB signaling pathways in lung cells [52].

Accordingly, the G compound can inhibit oxidative stress and inflammatory response by attenuating the activity of the Hmgb1 and NF-κB signaling pathways, with decreased levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) in lung cells [53]. Moreover, G increases glutathione-S-transferase (GSTs) levels, decreases MDA, and negatively regulates the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) in liver cells [54]. G compound has been shown to suppress NF-κB pathway through inhibiting the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in renal cells [55] and reducing the formation of intracellular ROS. Moreover, an activation of the AMP/nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor-2 (NRF2) pathways in vitro was observed, positively regulating the antioxidant enzymes, HO-1, NQO-1, and GCLC and negatively regulating TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [56].

According to descriptions, GA also suppresses oxidative stress and neuroinflammation induced by A1C13 through TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway inhibition [57]. In accordance, one study has observed that GA was able to attenuate oxidative stress and neuroinflammation induced by rotenone reducing the activation of the ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule-1 (Iba-1), preventing glutathione depletion, lipid peroxidation inhibition, and attenuation of the induction of COX-2 and iNOS [58]. In addition, a restored mitochondrial complex I and IV, a reduction in the generation of ROS, the release of Cytochrome C, and ultimately cell apoptosis inhibition after exposure to GA in brain tissue of adult Sprague Dawley Rats were observed [59].

GA can suppresses lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis through activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, and inhibition of the NF-κB in renal cells [60]. GA also suppresses oxidative stress and inflammation through activation of the NRF-2 and HO-1 pathways and IκB and NF-κB p65 signaling inhibition in cardiac cells [61].

In the liver tissue of rats, GA inhibits NTiO2-induced apoptosis by superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activation [61]. Moreover, it has been shown that GA can inhibit caspase-3 and -9 at mitochondria in HepG2 cells, positively and negatively regulating Bcl-2 and Bax proteins expression, respectively [62] (

Table 1)

.

Table 1.

Summary of studies showing the autoinflammatory and anti-tumoral effects of G, GA, and DPG.

| Model | Compound (Dose) | Mechanism | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro (KATO III and HL-60) | G (1 to 10 mg/mL) | Antitumor activity ↑ apoptosis | [23] | |

| In vitro (HLE, KATO III, and HL-60) | G (0.1 to 1 mg/mL) | Antitumor activity ↑ apoptosis | [24] | |

| In vitro (DU-145 and LNCaP) |

G (1 to 20 mM) | Antitumor activity ↑ apoptosis | [25] | |

| In vitro (Caco3, HT29, and RAW 264.7) In vivo (Acute lung injury mice model) |

DPG (300 µM) DPG (3 and 8 mg/kg/day) |

↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, as well as HMGB1 receptors, RAGE and TLR4 | [34] | |

| In vitro (neutrophils) | G (0.05, 0.5, and 5.0 µg/mL) | ↓ ROS | [38] | |

| In vivo (Con A-induced hepatitis) Ex vivo (liver dendritic cells) |

G (2 mg/mouse) G (0.1 mg/mL) |

↑ IL-10 and ↓ liver inflammation | [39] | |

| In vitro (U251) | GA (1, 2, 4 mM) | Anticancer effect ↓ proliferation and ↑ apoptosis possibly related to the NF-κB mediated pathway | [56] | [40] |

| In vitro (U87MG and T98G) | DPG (0.1 to 2 mM) | Anticancer effect ↓ proliferation and ↑ apoptosis. ↓ NF-κB pathway | [57] | [46] |

| In vivo (DSS-induced colitis mice model) | DPG (8 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, at the earlier stages, ↓ inflammation though AMPK-COX-2-PGE. At later times ↓ iNOS and COX-2 in HMGB1-dependent manner | [42] | [49] |

| In vivo (mechanical thrombectomy rat model) | G (2, 4 and 10 mg/kg/day) | ↓ HMGB1 and its downstream inflammatory factors, and ↓ oxidative stress |

[43] | [50] |

| In vivo (Focal cerebral I/R injury rat model) | G (4 mg/kg/day) | ↓ HMGB1 and ↑ apoptosis through the blockage of the JNK and p38 | [44] | [51] |

| In vivo (Sepsis-induced acute lung injury rat model) | G (25 and 50 mg/kg/day) | ↓ inflammatory responses, oxidative stress damage, and apoptosis though ↓ NF-κB, JNK, and p38 MAPK |

[45] | [52] |

| In vivo (Acute lung injury mice model) | G (20 and 40 mg/kg/day) | ↓ LPS-induced lung injury via blocking HMGB1/TLRs/NF-κB pathway | [46] | [53] |

| In vitro (RAW 264.7 and bone marrow monocytes) | G (25 to 100 µM) | ↓ RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and oxidative stress through ↑ AMPK/Nrf2 and ↓ NF-κB and MAPK | [49] | [56] |

| In vivo (Parkinson rat model) | GA (50 mg/kg/day) | ↓ dopamine neuron loss and ↓ Iba-1 and GFAP ↑ antioxidant enzyme activity, ↓ lipid peroxidation, ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines |

[51] | [58] |

| In vivo (Vascular dementia rat model) | GA (20 mg/kg/day) | ↓ release of cytochrome-c and ↑ Bcl2, and ↑ the endogenous antioxidants |

[52] | [59] |

| In vitro (HBZY-1) In vivo (sepsis-induced acute kidney injury mice model) |

GA (50 and 100 µM) GA (25 and 50 mg/kg/day) |

↓ oxidative stress via ↑ ERK signaling pathway. ↓ NF-κB | [53] | [60] |

| In vivo (myocardial ischemic injury-rat model) | GA (10 and 20 mg/kg/day) | ↓ oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines. ↑ Nrf2 antioxidant response ↓ NF-κB activation |

[54] | [61] |

| In vitro (HEPG2) | G (5, 25 and 125 µg/mL) | ↓ H2O2-induced oxidative stress, ↑ apoptosis | [55] | [62] |

| In vitro (HT29) | GA (1, 5 and 10 µM) | ↓ TNF-α-mediated IL-8 through ↓ MAPK and the IKB/NF-κB pathway | [58] | [63] |

| In vivo (DSS-induced colitis mice model) | GA (10 and 50 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, ↓ inflammation by regulating COX-2 and NF-κB | [59] | [64] |

| In vivo (rat model of ulcerative colitis) | G (40 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, ↓ inflammatory injury via suppression of NF-κB, TNF-α, and ICAM-1 |

[60] | [65] |

| In vivo (TNBS-induced experimental colitis mice model) | G (10, 30 and 90 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, ↓ IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-17 and ↑ IL-10 | [61] | [66] |

| In vivo (DSS-induced colitis rat model) | G (2 mg rectally) | ↓ colitis, ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, Cxcl-2, Mcp1, and MPO | [62] | [67] |

| In vivo (TNBS-induced experimental colitis rat model) | GA (2, 10 and 50 mg/kg, rectally and 10 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, ↓ serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, ↓ colon MPO and MDA, and ↑ SOD | [63] | [68] |

| In vivo (rat model of ulcerative colitis) | G (100 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, when combined with emu synergistically ↓ of PPARγ and TNF-α | [64] | [69] |

| In vivo (TNBS-induced experimental colitis mice model) | G (50 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, ↓ HMGB1 on DC/macrophage mediated Th17 proliferation | [65] | [70] |

| In vivo (indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury mice model) | GA (100 mg/kg/day) | ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, ↑ indomethacin-induced small intestinal damage | [66] | [71] |

| In vivo (DSS-induced colitis mice model) | G (100 mg/kg/day) | ↓ colitis, regulated the phosphorylation of transcription factors such as NF-κB p65 and IκB α | [67] | [72] |

| In vivo (DSS-induced colitis mice model) | DPG (8 mg/kg/day) | ↑ mucosal healing by ↓ CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL5, PTGS2, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL12, CCL7; ↑ wound healing genes COL3A1, MMP9, VTN, PLAUR, SERPINE, CSF3, FGF2, FGF7, PLAT, TIMP1 and ↑ extracellular matrix remodeling genes, VTN, and PLAUR |

[68] | [73] |