Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Adolfo Fernádez Fernández and Version 2 by Amina Yu.

Francisco Conde-Valvís’s so-called “stone treasure” is a set of unique carved stone pieces, such as bases, column shafts, a mortar, and decorated fragments (trisqueles and rosettes), found during the 2018 excavation campaign in the Cibdá de Armea (Allariz, Ourense). They had been piled up and re-buried—no records existed as to where—at the western end of the Finca de A Atalaia, which was excavated in the 1950s under the direction of Conde-Valvís and began to be excavated again in 2011.

- conservation–restoration

- musealisation

- Roman sites

- Galicia

1. Introduction

The 2018 excavation season at the western end of the Atalaia sector, in the Roman site of Armea, led to the discovery of a significant assemblage of stone fragments, including columns, millstones, and decorative elements. Following the initial confusion, these pieces were eventually identified as the stone elements found by Francisco Conde-Valvís during his excavations in the 1950s, which had been initially stored near the perimeter wall of the estate and which, over time, had become interred and forgotten, as no extant records existed about their whereabouts. In 2019, the state of preservation and interpretation of these pieces was thoroughly reviewed, and the texts, plans, drawings, and photographic records of the old excavations were exhaustively examined, in order to establish the original archaeological context of these elements, which were collectively referred to as “Conde-Valvís’s stone hoard”. After determining their archaeological context, the restoration team was able to put them back in their original position, making the site easier to understand for visitors. The main objective is to present the process that led to the restitution of these pieces to their original location at the site. The result of the intervention fills a gap in the archaeological research and publication about this type of archaeological and conservation–restoration processes in northwestern Spanish sites.

The 2018 excavation season at the western end of the Atalaia sector, in the Roman site of Armea, led to the discovery of a significant assemblage of stone fragments, including columns, millstones, and decorative elements. Following the initial confusion, these pieces were eventually identified as the stone elements found by Francisco Conde-Valvís during his excavations in the 1950s, which had been initially stored near the perimeter wall of the estate and which, over time, had become interred and forgotten, as no extant records existed about their whereabouts. In 2019, the state of preservation and interpretation of these pieces was thoroughly reviewed, and the texts, plans, drawings, and photographic records of the old excavations were exhaustively examined, in order to establish the original archaeological context of these elements, which were collectively referred to as “Conde-Valvís’s stone hoard”. After determining their archaeological context, the restoration team was able to put them back in their original position, making the site easier to understand for visitors. The main objective is to present the process that led to the restitution of these pieces to their original location at the site. The result of our intervention fills a gap in the archaeological research and publication about this type of archaeological and conservation–restoration processes in northwestern Spanish sites.

2. The Roman Site of Armea

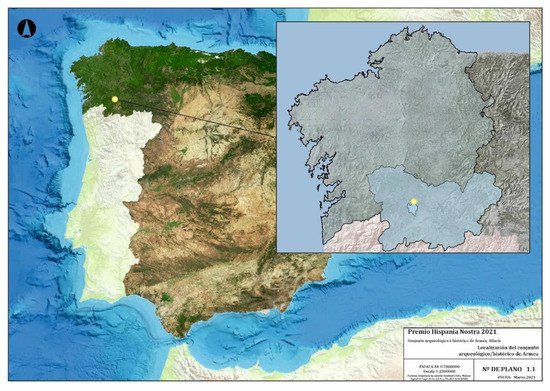

Cibdá de Armea, also known as Hillfort of Armea, is part of the historical–archaeological complex of Armea, which spreads around the eponymous hill, 15 km distance from Ourense, northwest of Spain (2. The Roman Site of Armea

Cibdá de Armea, also known as Hillfort of Armea, is part of the historical–archaeological complex of Armea, which spreads around the eponymous hill, 15 km distance from Ourense, northwest of Spain (

Figure 1

). In the Roman period, this area was in the northwest of the Conventus Bracarensis (ancient Roman province of Gallaecia). The hill is part of a low mountain range (average altitude of 600 m. a. s. l) that separates the Miño River basin to the north—specifically the A Rabeda valley, tributary of the Miño—and the Arnoia valley to the south. The complex (

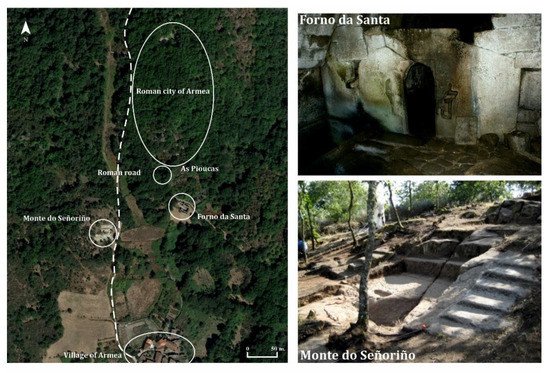

Figure 2) comprises a wide variety of archaeological sites, spanning the pre-Roman period and the Late Middle Ages. The most significant sites are the Roman city of A Cibdá, the Basilica of the Ascension and Forno da Santa [1][2][3][4][5] (pp. 77–100), the Roman road-Camino de Santiago, and the Late Medieval settlement of Santa Mariña [6], as well as a large number of scattered stone finds (for example, warrior torsos, triskelia, severed stone heads) [3] (p. 24). The Roman settlement of Señoriño, situated at the foot of the historical path leading up to the Cibdá, has recently been excavated and musealised [4][7][8]. This path currently links the Camino de Santiago and the Vía de la Plata and is probably a fossilised secondary Roman road running from Chaves (Aquae Flaviae) to Lugo (Lucus Augusti).

) comprises a wide variety of archaeological sites, spanning the pre-Roman period and the Late Middle Ages. The most significant sites are the Roman city of A Cibdá, the Basilica of the Ascension and Forno da Santa [6,7,8,9,10] (pp. 77–100), the Roman road-Camino de Santiago, and the Late Medieval settlement of Santa Mariña [11], as well as a large number of scattered stone finds (e.g., warrior torsos, triskelia, severed stone heads) [8] (p. 24). The Roman settlement of Señoriño, situated at the foot of the historical path leading up to the Cibdá, has recently been excavated and musealised [9,12,13]. This path currently links the Camino de Santiago and the Vía de la Plata and is probably a fossilised secondary Roman road running from Chaves (Aquae Flaviae) to Lugo (Lucus Augusti).

Figure 1.

Location of the historical–archaeological complex of Armea. Sources: IGN and ESRI.

Figure 2. Elements in the historical–archaeological complex of Armea.

Elements in the historical–archaeological complex of Armea.

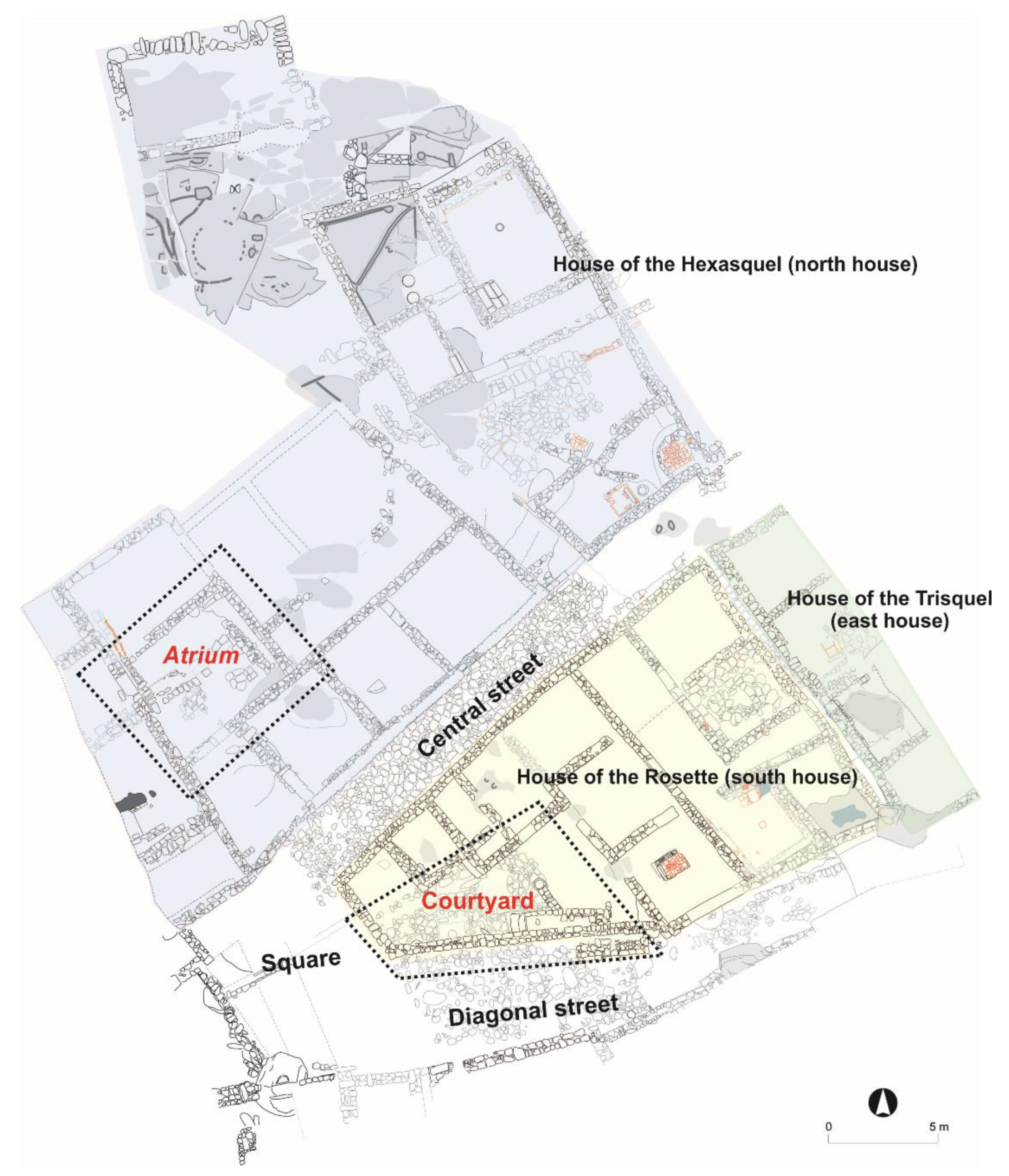

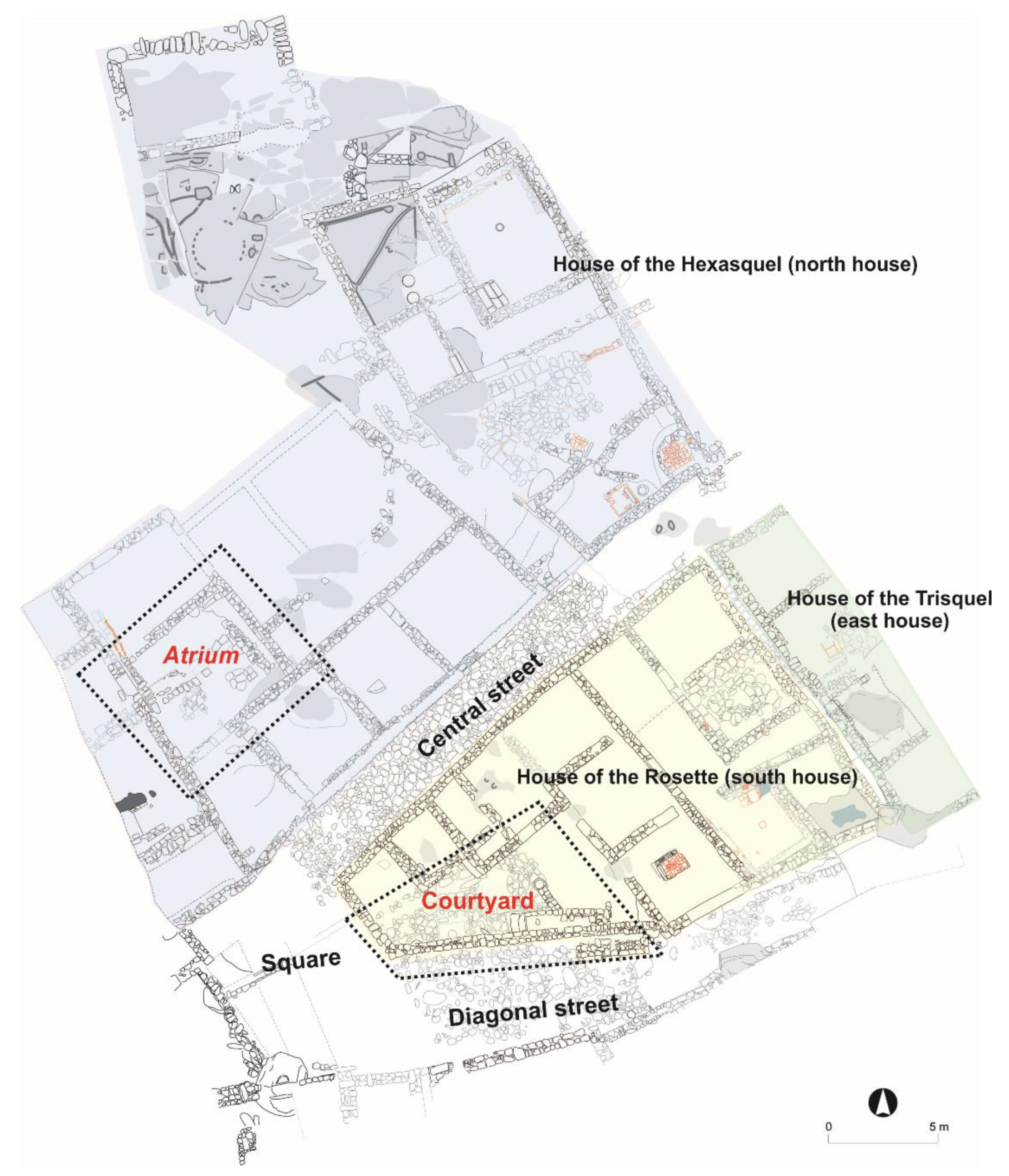

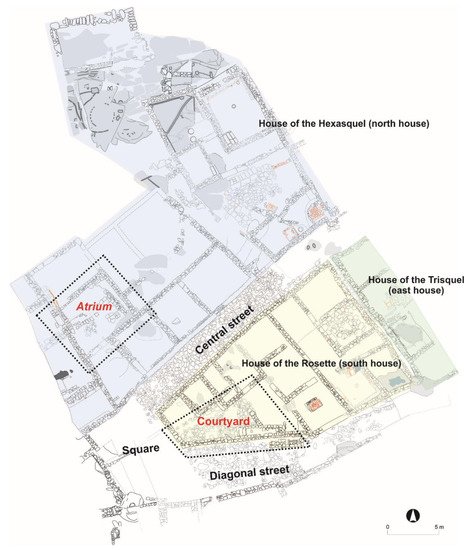

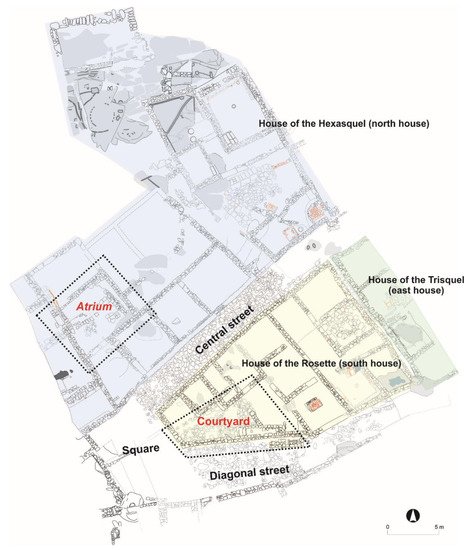

Cibdá de Armea is situated on the hill’s northern slope. In the 1950s, a series of Roman courtyard houses were excavated in a terrace known as A Atalaia, flanking a stone-paved street [14]. Systematic excavation of this area was resumed in 2011. Initially, the excavation focused on re-excavating the 1950s trenches, but from 2014, the stratigraphic excavation of new areas began under the direction of a team from the University of Vigo. To date, this has resulted in the full excavation of two atrium houses and the partial excavation of another one. This house type is rare in Roman sites in rural contexts in northwest Spain (

Figure 3). One of the earliest occupation phases, from the late 1st to the late 2nd or early 3rd centuries AD, was eminently Roman in character. Thus far, the stratigraphy suggests that there is a hiatus in occupation between the Late Roman and the Late Medieval period. An earlier occupation phase (early to late 1st century AD) has been attested in A Atalaia, which is coetaneous to the construction of Monte do Señoriño [10], as revealed by the ceramic record—Italic and south-Gallic terra sigillata, Baetican amphorae, indigenous wares—and razed architectural features under the large houses [7][11]. The analysis of the ceramic contexts found during the recent excavations has allowed to outline the occupation sequence of Armea [7][11]. Everything suggests that this terrace was first occupied in the early 1st century AD, contemporaneously to the construction of the area of O Señoriño on the site’s outskirts [5]. Evidence for this period includes a series of domestic and industrial (metal smelting) features found under the house of the Hexasquel and the main thoroughfare, which have been dated, based on the ceramic assemblage, to the final years of Augustus’s or the beginning of Tiberius’s reigns [11] (pp. 864–866). The original Roman constructions were modified in the mid-1st century AD and eventually razed to the ground with the re-urbanisation of the sector surrounding the streets, where new large houses were built, probably in the late 1st century AD, during the Flavian period. The area was abandoned between the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries AD, for reasons that remain unclear [11] (pp. 867–871).

). One of the earliest occupation phases, from the late 1st to the late 2nd or early 3rd centuries AD, was eminently Roman in character. Thus far, the stratigraphy suggests that there is a hiatus in occupation between the Late Roman and the Late Medieval period. An earlier occupation phase (early to late 1st century AD) has been attested in A Atalaia, which is coetaneous to the construction of Monte do Señoriño [15], as revealed by the ceramic record—Italic and south-Gallic terra sigillata, Baetican amphorae, indigenous wares—and razed architectural features under the large houses [12,16]. The analysis of the ceramic contexts found during the recent excavations has allowed us to outline the occupation sequence of Armea [12,16]. Everything suggests that this terrace was first occupied in the early 1st century AD, contemporaneously to the construction of the area of O Señoriño on the site’s outskirts [10]. Evidence for this period includes a series of domestic and industrial (metal smelting) features found under the house of the Hexasquel and the main thoroughfare, which have been dated, based on the ceramic assemblage, to the final years of Augustus’s or the beginning of Tiberius’s reigns [16] (pp. 864–866). The original Roman constructions were modified in the mid-1st century AD and eventually razed to the ground with the re-urbanisation of the sector surrounding the streets, where new large houses were built, probably in the late 1st century AD, during the Flavian period. The area was abandoned between the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries AD, for reasons that remain unclear [16] (pp. 867–871).

Figure 3. Plan of the excavated Roman settlement in A Atalaia.

3. The Atrium of the House of the Hexasquel

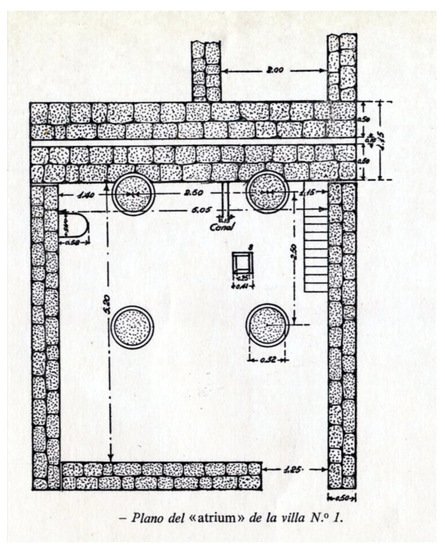

Conde-Valvís [9] (pp. 479–483) describes an atrium with four column bases at its centre, forming a perfect square with 2.5 m sides ( Plan of the excavated Roman settlement in A Atalaia.

The complex of Armea is surrounded by legends and vernacular traditions. Ritual activity is attested at the site before the Roman period, and over time, legend became one with the archaeological remains. Traditional accounts relate the remains to the martyrdom of Saint Mariña, a 2nd-century legend. According to these accounts, Mariña was burned in the sauna beneath the basilica; the “Pioucas” are a former Roman wine press where Mariña went to take a fresh bath after her martyrdom, etc. [17].

3. The Atrium of the House of the Hexasquel

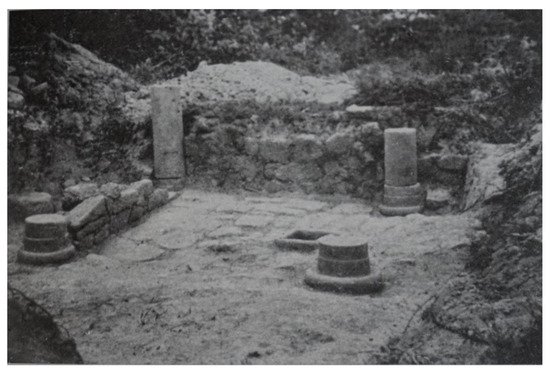

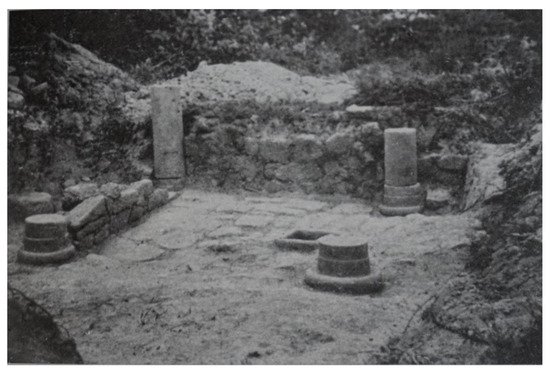

Conde-Valvís [14] (pp. 479–483) describes an atrium with four column bases at its centre, forming a perfect square with 2.5 m sides (

Figure 4 and

8 and

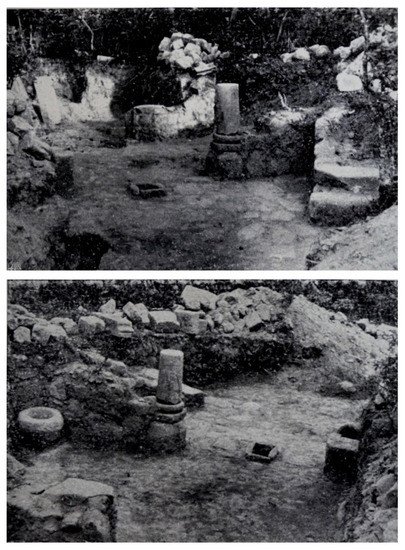

Figure 5). He also found two column shaft fragments among the debris, which Valvís placed over the bases, somewhat randomly, to take a picture of the courtyard. It has been impossible to establish whether a capital was also found, as the text is unclear in this regard. Although at first he writes that none of the four capitals were found, it was claimed that three of the four capitals were missing, so this suggests that at least one of them was found. The atrium was paved with small, unevenly sized, stone slabs, and a channel ran across the room from E to W; a square drain, similar to that which is still visible in the southern domus, was also identified. Conde-Valvís uses the terms impluvium and compluvium incorrectly. He refers to the square drains in the atrium and the courtyards of both houses as compluvium and to the paved areas as impluvium. Interpreting this small drain, used to evacuate rainwater, as a compluvium is a mistake, for compluvia are the openings left on the roofs of atria to let in light and air, as well as to let rainwater fill the impluvium, a pool from which water ran into the house’s waterpipe system. In Armea, rainwater entered through this opening, which can be regarded as a compluvium, but not into an impluvium, but directly onto the paved floor. Rainwater filtered through the stone slabs and was channelled to the rest of the house through the quadrangular drain and a stone channel built beneath the pavement.

9). He also found two column shaft fragments among the debris, which Valvís placed over the bases, somewhat randomly, to take a picture of the courtyard. It has been impossible to establish whether a capital was also found, as the text is unclear in this regard. Although at first he writes that none of the four capitals were found, in the same article, he claims that three of the four capitals were missing, so this suggests that at least one of them was found. The atrium was paved with small, unevenly sized, stone slabs, and a channel ran across the room from E to W; a square drain, similar to that which is still visible in the southern domus, was also identified. In his article, Conde-Valvís uses the terms impluvium and compluvium incorrectly. He refers to the square drains in the atrium and the courtyards of both houses as compluvium and to the paved areas as impluvium. Interpreting this small drain, used to evacuate rainwater, as a compluvium is a mistake, for compluvia are the openings left on the roofs of atria to let in light and air, as well as to let rainwater fill the impluvium, a pool from which water ran into the house’s waterpipe system. In Armea, rainwater entered through this opening, which can be regarded as a compluvium, but not into an impluvium, but directly onto the paved floor. Rainwater filtered through the stone slabs and was channelled to the rest of the house through the quadrangular drain and a stone channel built beneath the pavement.

Figure 48.

Photograph of the atrium after the excavation (Conde-Valvís 1959: Plate I).

Figure 59. Plan drawn by Conde-Valvís in 1955 (Conde-Valvís 1959: 482).

Plan drawn by Conde-Valvís in 1955 (Conde-Valvís 1959: 482).

Conde-Valvís finishes his description by saying that, a few days after closing the excavation and taking the picture “[…] a group of vandals walked by, grounded the columns, took the bases out of place, yanked at the slabs […], in short, these soulless miscreants left behind them the mark of barbarism” [14] (pp. 481–483). After this incident, the soil beneath the slabs could be excavated. Nothing is said about whether the vandalised elements were destroyed, stolen, or partially recovered. The 2018 excavation revealed that at least some of them had remained on site and had been interred by the excavators at the edge of the property, next to the atrium. At the end of the excavation, the trenches, including this atrium, were backfilled [20].

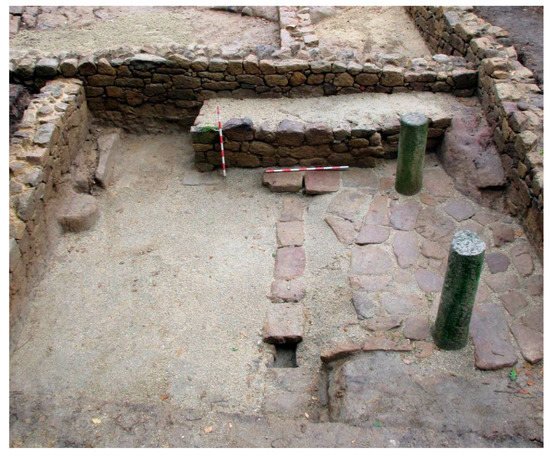

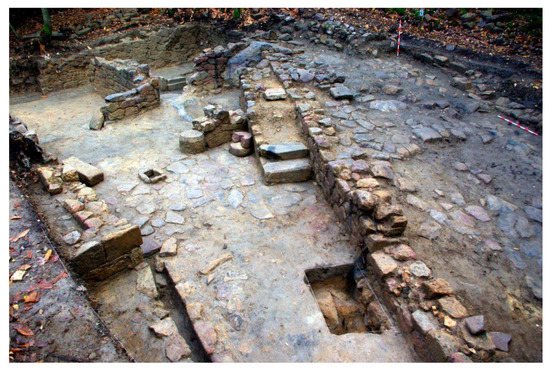

The consolidation and musealisation works in 2018 included raising the walls by adding a few protective courses and the restitution of part of the pavement and the drain lids, using slabs found among the fills that covered the rooms (

Figure 6 and

10 and

Figure 7). Additionally, in the words of the director of the excavations, “In order to present a discourse that is closer to reality, two fragments of Roman columns found in the vicinity were placed on the bases, conveying an image that helps to reflect the archaeological discourse” [13] (pp. 89–90). After consulting some of the archaeologists, it was concluded that the original location of these column shafts cannot be established with any certainty, and that it is not even clear that they belong to Armea. They were brought to the site in 2014 from the house where they were found out of context in Allariz’s historical quarters. The analysis of their raw material (granite), morphology and typology, and their comparison with other columns found in the archaeological context in Armea, strongly suggest that they are foreign to the Cibdá, and they cannot even be securely dated to the Roman period to which the site is dated. Following this, it was decided to remove these columns, especially after the original column shafts were found in “Conde-Valvís’s stone hoard”.

11). Additionally, in the words of the director of the excavations, “In order to present a discourse that is closer to reality, two fragments of Roman columns found in the vicinity were placed on the bases, conveying an image that helps to reflect the archaeological discourse” [20] (pp. 89–90). After consulting some of the archaeologists, it was concluded that the original location of these column shafts cannot be established with any certainty, and that it is not even clear that they belong to Armea. They were brought to the site in 2014 from the house where they were found out of context in Allariz’s historical quarters. The analysis of their raw material (granite), morphology and typology, and their comparison with other columns found in the archaeological context in Armea, strongly suggest that they are foreign to the Cibdá, and they cannot even be securely dated to the Roman period to which the site is dated. Following this, it was decided to remove these columns, especially after the original column shafts were found in “Conde-Valvís’s stone hoard”.

Figure 610.

State of the courtyard after the 2014 excavation. Photograph: David Pérez.

Figure 711. Final state of the atrium after the restoration works in 2014. Photograph: David Pérez.

4. The Courtyard of the Domus of the Rosette

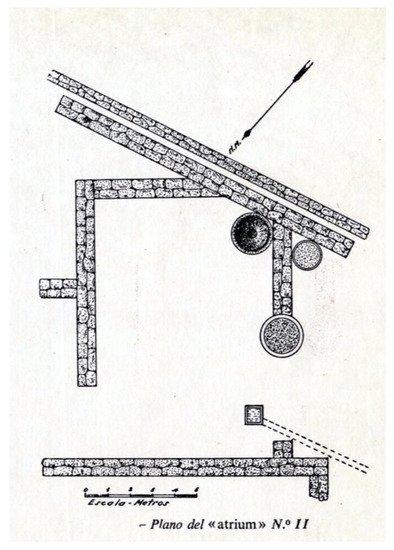

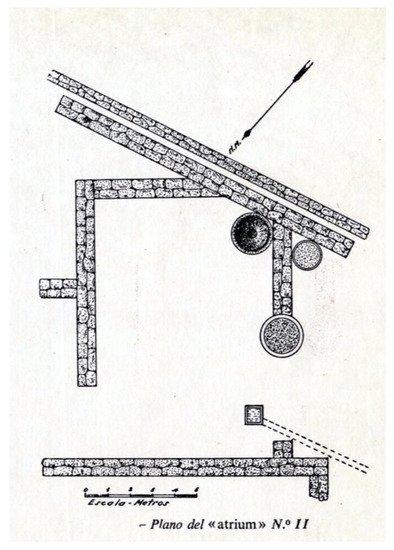

Conde-Valvís [9] (pp. 483–484) describes this courtyard as a floor paved by small, unevenly sized, stone slabs, with a channel running across it, from E to W, and a compluvium built with four stones, 0.12 m thick, forming a square deposit with 0.25 m sides (inner measurements). A staircase on the south side of the wall gave access to an upper storey. A small wall projects from the staircase towards the centre of the courtyard. It is 0.80 m long and 0.40 m thick, and it ends in a crudely carved granite block, which is approximately 0.50 m high ( Final state of the atrium after the restoration works in 2014. Photograph: David Pérez.

4. The Courtyard of the Domus of the Rosette

Conde-Valvís [14] (pp. 483–484) describes this courtyard as a floor paved by small, unevenly sized, stone slabs, with a channel running across it, from E to W, and a compluvium built with four stones, 0.12 m thick, forming a square deposit with 0.25 m sides (inner measurements). A staircase on the south side of the wall gave access to an upper storey. A small wall projects from the staircase towards the centre of the courtyard. It is 0.80 m long and 0.40 m thick, and it ends in a crudely carved granite block, which is approximately 0.50 m high (

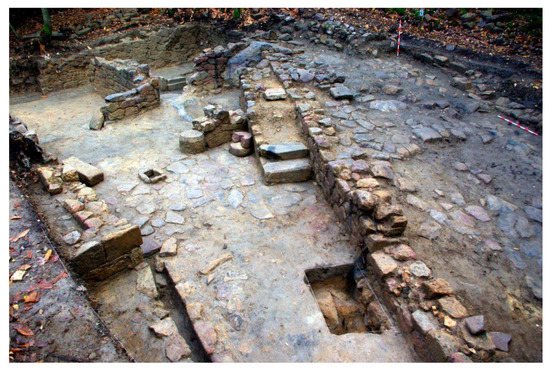

Figure 8). In his publication, Conde-Valvís, along with the general arrangement of the courtyard, describes different architectural elements found during his excavation, including the base of a column that probably sat on the granite block and a column shaft fragment which he placed on the base to take a photograph (

12). In his publication, Conde-Valvís, along with the general arrangement of the courtyard, describes different architectural elements found during his excavation, including the base of a column that probably sat on the granite block and a column shaft fragment which he placed on the base to take a photograph (

Figure 9). He also describes a mortar found to the east of the small wall. Finally, he mentions a fragmentary millstone that sat vertically on the channel, acting as a water sluice. Like with the atrium in the house of the Hexasquel, the building was backfilled after the excavation. Again, no information is provided as to the whereabouts of the stone elements found, whether they were interred in situ, or taken to a different location.

13). He also describes a mortar found to the east of the small wall. Finally, he mentions a fragmentary millstone that sat vertically on the channel, acting as a water sluice. Like with the atrium in the house of the Hexasquel, the building was backfilled after the excavation. Again, no information is provided as to the whereabouts of the stone elements found, whether they were interred in situ, or taken to a different location.

Figure 913. Several views of the courtyard of the Rosette after excavation [9] (Conde Valvís 1959: Plate II).

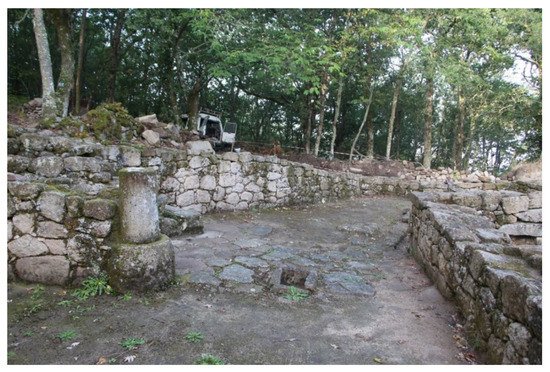

Between 2011 and 2012, the City Council of Allariz resumed the excavation of this area; the excavation was directed by David Pérez. The loose objects described by Valvís could not be found, except for a few threshold stones that had been piled near the site (

Figure 10 and

4 and

Figure 11). The crude granite base was found in situ, and a small column shaft found near the estate’s perimeter wall was placed on top, in an attempt to recreate Valvís’s old photographs [13] (p. 89).

5). The crude granite base was found in situ, and a small column shaft found near the estate’s perimeter wall was placed on top, in an attempt to recreate Valvís’s old photographs [20] (p. 89).

Figure 104.

View of the atrium of the Domus of the Rosette after the 2011 excavations. Photograph: David Pérez.

Figure 115. View of the site after the 2011 and 2012 works: Photograph: Council of Allariz.

View of the site after the 2011 and 2012 works: Photograph: Council of Allariz.