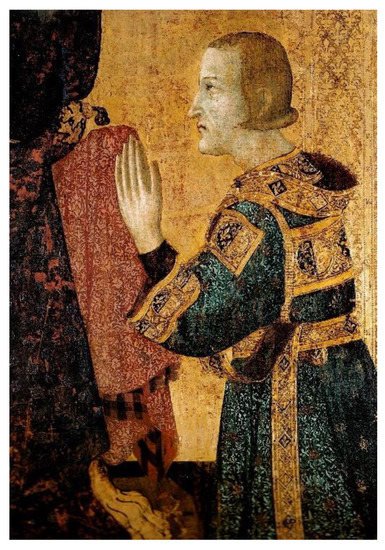

Robert of Anjou King of Sicily (1309–1343). Robert of Anjou was the third king of the Angevin dynasty on the throne of Sicily. He ruled from 1309 to 1343, but, in these years, Sicily was under the domain of the Aragonese dynasty and, hence, his authority was limited to the continental land of the Kingdom and his court was mainly focused in the city of Naples. From an iconographic point of view, he is particularly interesting because, between his official representations (namely, commissioned directly by him or his entourage), he was the first king of Sicily who made use not only of stereotyped images of himself, but also of physiognomic portraits. In particular, this entry focuses on these latter items, comprising the following four artworks: Simone Martini’s altarpiece, the Master of Giovanni Barrile’s panel, the Master of the Franciscan tempera’s canvas, and the so-called Lello da Orvieto’s fresco.

- royal images

- royal iconography

- kings of Sicily

- kings of Naples

- Angevin dynasty

- Robert of Anjou

Introduction

References

- Caggese, R. Roberto d’Angiò e i suoi tempi; Bemporad: Firenze, Italy, 1922–1930.

- Hébert, M. Le règne de Robert d’Anjou. In Les Princes angevins du XIIIe au XVe siècle. Un destin européen; Tonnerre, N.-Y., Verry, É., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Rennes: Rennes, France, 2003; pp. 99–116.

- Gaglione, M. Converà ti que aptengas la flor. Profili di sovrani angioini, da Carlo I a Renato (1266–1442); Lampi di stampa: Milano, Italy, 2009.

- Boyer, J.-P. Roberto d’Angiò, re di Sicilia-Napoli. In Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2017; Volume 87, ad vocem.

- Kelly, S. The New Solomon. Robert of Naples (1309–1343) and Fourteenth-Century Kingship; Brill: Leiden, The Netherland; Boston, MA, USA, 2003.

- Pryds, D.N. The King Embodies the Word: Robert d’Anjou and the Politics of Preaching; Brill: Leiden, The Netherland; Boston, MA, USA; Köln, Germany, 2000.

- Bock, N. La visione del potere. Cristo, il re e la corte angioina. In Cristo e il potere. Teologia, antropologia e politica; Andreani, L., Paravicini Bagliani, A., Eds.; SISMEL: Firenze, Italy, 2017; pp. 211–224.

- Weiger, K. The portraits of Robert of Anjou: self-presentation as political instrument? Journal of Art Historiography 2017, 9/2, 1–16.

- Perriccioli Saggese, A. Il ritratto a Napoli nel Trecento: l’immagine di Roberto d’Angiò tra pittura e miniatura. In La fantasia e la storia. Studi di Storia dell’arte sul ritratto dal Medioevo al Contemporaneo; Brevetti, G., Ed.; Palermo University Press: Palermo, Italy, 2019; pp. 37–46.

- Barbero, A. La propaganda di Roberto d’Angiò re di Napoli (1309–1343). In Le forme della propaganda politica nel Due e Trecento; Cammarosano, P., Ed.; École française de Rome: Roma, Italy, 1994; pp. 111–131.

- Dell’Aja, G. Cernite Robertum regem virtute refertum; Officine grafiche napoletane F. Giannini & Figli: Napoli, Italy, 1986.

- Vagnoni, M. La messa in scena del corpo regio nel regno di Sicilia. Federico III d’Aragona e Roberto d’Angiò; Basilicata University Press: Potenza, Italy, 2021.