Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Iveta Slavkova.

French artist and poet Camille Bryen (1907–1977) is usually, and always very briefly, cited as a member of the post-Second World War (1939–1945) lyrical abstraction trend in Paris, often designated as Ecole de Paris or Nouvelle Ecole de Paris, Tachisme, or Informel. Bryen painted hybrids of plants, animals, rocks, and humans, mixing the organic with the inorganic, evoking cellular agglomerations, geological structures, or prehistorical drawings. He emphasized the materiality and the process through thick impasto, visible brushstrokes, and automatic drawing. Along with other abstract painters in post-war Paris, Bryen’s work is usually associated with vague humanist interpretations and oversimplified existentialism.

- Abhumanism

- crisis of humanism

- post-World War II art

- School of Paris

1. Introduction

French artist Camille Bryen (1907–1977) is usually, and always briefly, cited as a member of the lyrical post-Second World War (1939–1945) abstraction trend in Paris. In his drawings, paintings, and etchings, Bryen figured hybrids of plants and animals, and mingled the organic with the inorganic; his paintings evoke cellular agglomerations and/or geological structures, and prehistorical abstract signs. Materiality and process are emphasized through thick impasto, visible brushstrokes, and automatism. According to the traditional interpretation framework of the post-war Parisian abstraction, these formal characteristics are a mix of a dramatic existential anguish and existentialist humanism. In other words, they are a logical reaction to the horrors of the Second World War (1939–1945) and the Holocaust, but also the affirmation of the infinite faith in the spiritual capacity of humans, embodied in innovative formal propositions, to overcome such plights thanks to the power of art (De Chassey and Ramond 2008, pp. 19–32).

If this could correspond to the production of some post-war abstractionists, it certainly does not match Bryen’s. First, this was not the way he himself approached his art, and art in general. Second, if wresearchers scrutinize his work in its totality—his abstract paintings, actions, installations, objects, photographs, poems, and objects—weresearchers will quickly understand that his rejection of any pretension toward spirituality, universalism, and humanism, as well as his biting critique, do not linger over anguish, even though he was probably not exempted from the syndrome of post-war anxiety. This is, at least, what his still largely understudied theoretical writings on “Abhumanism” are telling us. Elaborated together with his close friend, the playwright, writer, and occasional draughtsman Jacques Audiberti (1899–1965), who coined the term at the end of the 1940s, Abhumanism claimed that when faced with the rawness and cruelty of recent history, the lyrical humanism in art was merely fallacious. They called for a radical revision of the humanist subject, including anthropocentrism, convinced that the deflation of the humanist pretension would lead to a renewed vitalism. Audiberti affirmed repeatedly that painting was the abhumanist activity par excellence, and that Bryen was the best example he could think of. Approaching Bryen’s work through the lens of Abhumanism, connects the artist to the history of the avant-garde (mostly Dada and also Surrealism), and points to the relevance of Abhumanism as a prolongation of the reflection of the avant-garde on the crisis of humanism generated by the First World War (1914–1918), and confirmed by the second world conflict.

The historical obliteration of Abhumanism, and other “minor” trends in the post-war Parisian arts scene, has been systematic and has contributed to the canonical vision of the “decline” of Paris after the Second World War, directly linked to the narrative of the rise and fall of lyrical abstraction itself (Giroud 2008, pp. 6–8; Flahutez 2011, pp. 23–35; Slavkova 2021, pp. 90–97), and the subsequent “triumph” of American art (Dossin 2014). Bryen was somehow trapped in these narratives—one of the most popular figures of the post-war Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood in Paris around the Second World War (Camille Bryen 1997, pp. 163–64), he was almost totally forgotten when the art world made a shift from abstraction to more objective art forms (Pop Art, Neo-Dada, Nouveau Réalisme, Figuration Narrative, etc.) in the 1960s. Since then, his work has remained understudied and undervalued.

2. Who Is Camille Bryen?

Born in Nantes in 1907, Camille Briand (his real name) moved to Paris sometime in 1929–1930 (Camille Bryen 1997, pp. 161–65). Already known in the bohemian avant-garde poetic circles in Nantes, he settled in Montparnasse, then in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and quickly became a well-known socialite whose company and humor were appreciated. His first one-man show took place in May 1934 at the independent Le Grenier venue in the Latin Quarter, and featured Surrealism-inspired automatic drawings. It was followed by another exhibition in 1935, showing also automatic drawings, alongside the Swedish Surrealist Erik Olson (1901–1986) at the gallery Gravitations (Figure 1). The invitation for the opening on June 18 demonstrates the strong the impact of Surrealism on both artists. Olsen’s desertic dreamlike landscape with biomorphic shapes recalls Yves Tanguy; the hybrid unarticulated and highly eroticized hermaphrodite drawn by Bryen takes its cues from the Surrealist game cadavre exquis [exquisite corpse].

Figure 1. Invitation for the opening of the exhibition Eric Olson: Peintures/Camille Bryen: Dessins automatiques, 18 June–10 July 1935. Bryen Fund, Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Musée National d’Art Moderne/ Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Before the Second World War, Bryen displayed drawings at the Salon des Surindépendants in 1935, 1936, and 1938. He associated with independent venues such as the gallery La Fenêtre ouverte (February 1937) and the bar La Cachette (March 1937), where his works were shown alongside with those of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) and Francis Picabia (1789–1953) (Camille Bryen 1997, p. 169). In 1935, Bryen’s drawings were included in the first surrealist exhibition in Belgium, at the municipality of La Louvière, his first international exploit (Canonne 2012). His early drawings were purported to be destroyed but many of them reappeared in the “Bryen Fund” when it was given to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes (Rageot 1997, p. 78). Similar to the drawing reproduced on the Gravitations flyer, most of them represent incomplete, monstruous hybrids. Playing with the kingdoms of nature and subverting the hierarchy of the species, his drawings recall, as mentioned earlier, the surrealist “exquisite corpses”—figures whose sections are drawn blindly by different persons resulting in disquieting, bizarre figures. Bryen worked mostly with ink and pencil on paper, an easily transportable medium that allowed him to work everywhere. In some cases, he used headed paper from bars, such as the famous Montparnasse brasserie Le Dôme in Paris (Camille Bryen 1997, p. 87).

In parallel to these Surrealism-inspired drawings, Bryen wrote poetry, made objects and artists’ books, and gave extravagant conferences. For instance, on 6 April 1938, he gave a conference organized by the esoteric society “Groupe universaliste d’études traditionnelles” (Universalist group for traditional studies) with the ironic title “The occult without the occult” (Bryen Archives BRY n.d.,[1] Figure 2). In the poster, he qualified himself as an “illuminated by the Greek breasts”2, a pun on the homonymy of the French words sein (breast) and saint (saint), relating implicitly the sacred and the erotic, revealing another surrealist thread.

Figure 2. Poster for the conference “Camille Bryen, éclairé par les ‘seins grecs’, parlera de l’OCCULTE sans OCCULTE”, April 1938. Bryen Fund, Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Musée National d’Art Moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

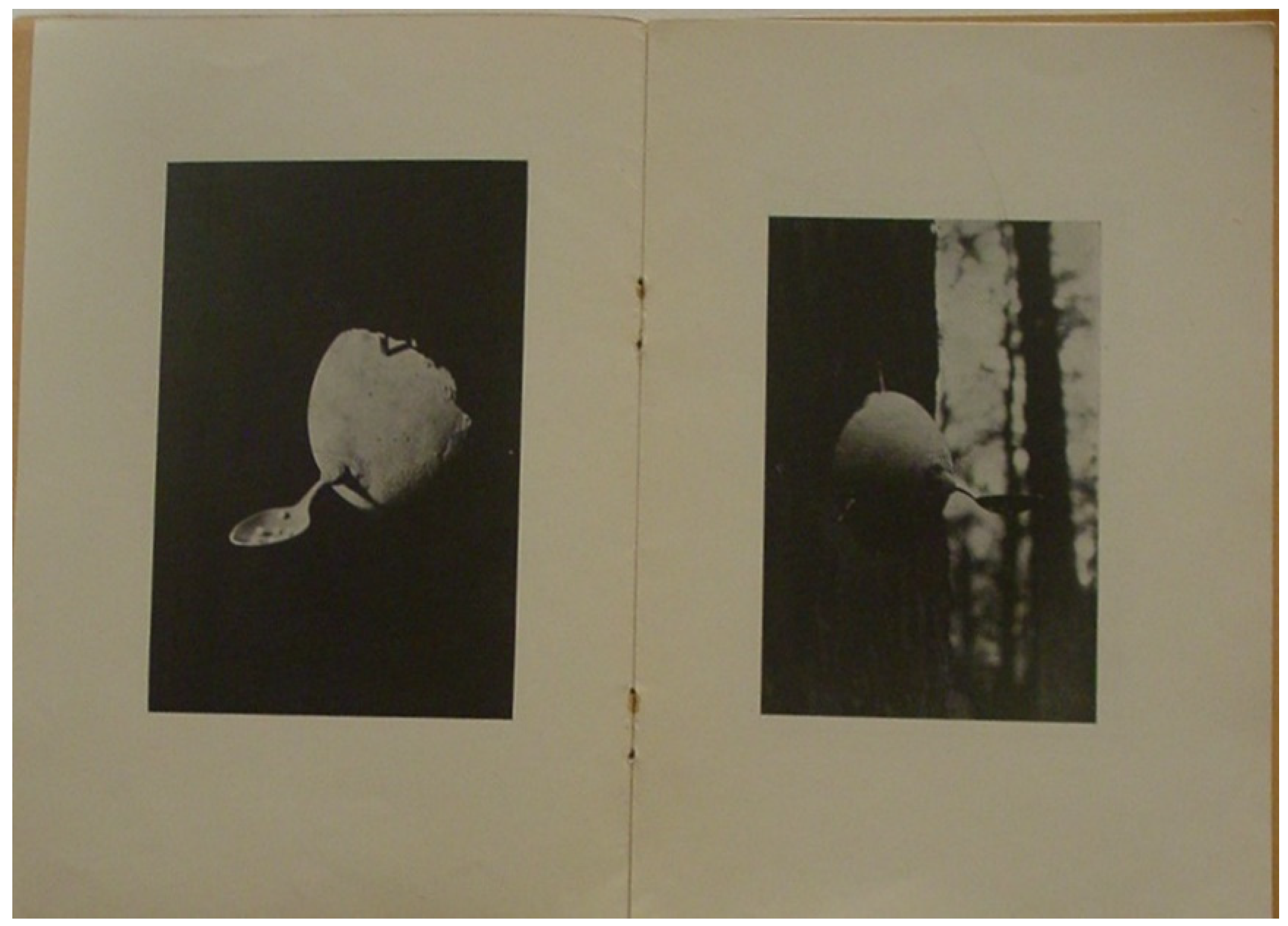

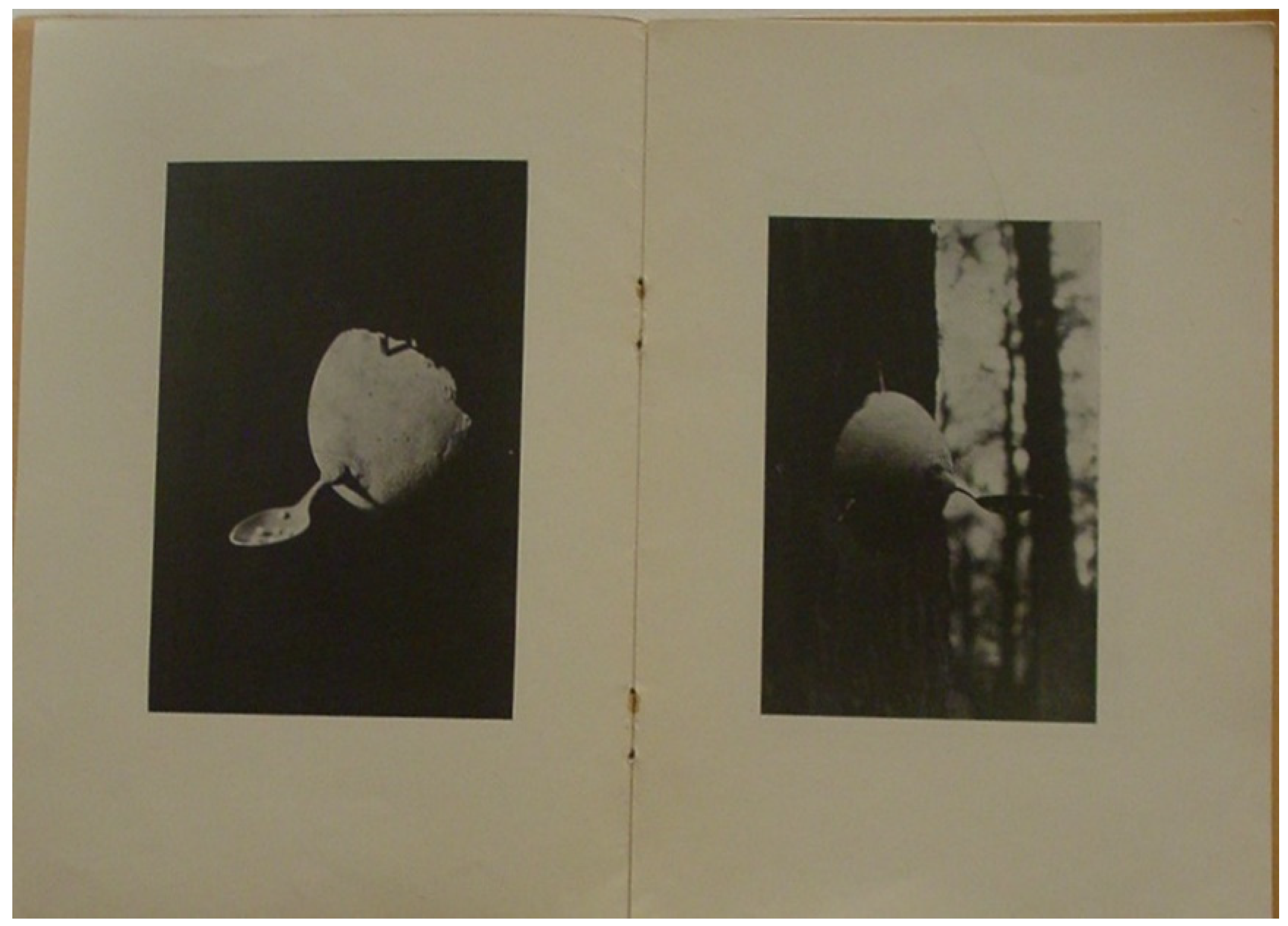

Bryen’s best known and most ambitious projects before World War II were collaborations with the photographer Raoul Michelet (known as Ubac, 1910–1985), who was then close to the Surrealists. Their first joint project, the book Actuation poétique (Poetic Actuation), called for an “actualized” poetry interacting with life. The authors wrote that they wanted to create “poetic public actions that require the actuation of poetry” (Bryen and Michelet 1935, p. 6), and added that “the poetic activity must participate in the life of the city like an anarchistic and disturbing ferment, profoundly amoral and in a state of permanent insurrection”. Their second project, L’Aventure des objets (The Adventure of the Objects, 1937), was the result of a conference Bryen gave at the Sorbonne, in which he took critical distance from the objects he had produced in the previous years (Bryen 1937). Like Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades and the surrealist objects of symbolic functioning, Bryen’s assemblages made irruption into the quotidian flow, emphasizing the erotic and the marvellous potential of banal objects and places. This is evidenced in one of the book’s best-known photographs—a breast grown on a tree, offering a spoon to the spectator (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Camille Bryen, Le sein dans la forêt (The Breast in the Forest), 1937. Extract from the book L’Aventure des objets, Paris: José Corti, pp. 8–9.

During the war years, Bryen fled Paris and his traces lead to Nantes, Bordeaux, and Lyons. He reached Marseilles where many avant-garde artists, namely a group of Surrealists, were hiding from the Vichy government; some of them, such as André Breton, Max Ernst, and Hans Bellmer, as well as his close friend Wols, applied more or less successfully for an exceptional visa for the United States through Varian Fry’s Emergency Rescue Committee (Varian Fry 1999; Slavkova 2020a). Bryen returned to Paris in April 1945 and became once again one of the most popular personalities of the effervescent Saint-Germain-des-Prés. A painting by the designer, architect, and filmmaker Georges Patrix (1920–1992) shows him as one of the “glories of the 6th arrondissement” next to Jean-Paul Sartre, Juliette Gréco, and Jacques Prévert (image published in Camille Bryen 1997, p. 159). Bryen is recognizable through his skinny, almost childish silhouette and his large smiling face adorned by prominent circular glasses. After the war, Bryen regularly exhibited his drawings, watercolors, and engravings and continued writing and publishing poems. He started painting with oils in 1949, producing works that intermingled the kingdoms of nature once again. Contrary to the automatic drawings from the 1930s, however, these paintings were more overtly abstract; yet, some motifs could recall insects, plants, and even humans, like in Hépérile discussed further below (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Camille Bryen, Hépérile, 1951. Oil on canvas, 146 × 89 cm. Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne/Centre Pompidou.

In the decade after the Liberation of France, Bryen affirmed himself as a central figure in the Parisian avant-garde. He was, according to Michel Giroud, completely “decentralized”, i.e., open-minded enough to bridge the conflicting trends coexisting in the city at the time: geometric and lyrical abstractionists, late Dada followers, Surrealists, Lettrists, and Zaoum sound poetry (Giroud 2008, p. 45/note 1). In the 1940s and 1950s, he took part in the epoch-making exhibitions of abstract painting in Paris: “L’Imaginaire” at the Luxembourg Gallery in December 1947, H.W.P.S.M.T.B at Collette Allendy in 1948, the now mythical “Véhémences confrontées” at Nina Dausset in 1951, which introduced Jackson Pollock to the French audience, and “Signifiants de l’Informel” organized by Michel Tapié at Studio Facchetti in 1952.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Bryen was honored by several institutional exhibitions, namely a one-man show at the Musée national d’Art moderne/Centre Pompidou in 1973 (Camille Bryen 1997, pp. 183–84). Philosopher and intellectual Umberto Eco considered his work to be a singular example of the Parisian post-war Informel (Eco 1965, p. 117). In 1976, the year before his death, Bryen was interviewed by Michel Butor for the influential among the intelligentsia French radio station “France Culture”; an innovative writer, Butor was a prominent representative of the Nouveau Roman trend. Art historian Jacqueline Boutet-Loyer established the catalogue raisonné of Bryen’s paintings in 1986, providing useful documentation on the works and the artist, based on archival research and conversations with Bryen and his wife Louysette (Boutet-Loyer 1986). More recently, the acquisition of Bryen’s archives by the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, the dedicated work of Vincent Rousseau (former curator of this museum), and Émilie Guillard, who runs the Fondation Bryen (Bryen Foundation), led to the major retrospective Camille Bryen à revers (which could be translated as “Bryen upside down”) in 1997 in Nantes (Camille Bryen 1997) and the digitalization of the archive documents accessible through the Fondation Camille Bryen/Fondation de France.3 In 2007, Guillard edited the complete writings of Bryen, published at the Presses du réel (Dijon) in the collection “L’Écart absolu” created by Michel Giroud (Bryen 2007). Despite these honors, Bryen, as he put it himself, has remained the “best-known of the unknown” (Clair 1971, p. 15).