Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Estefanía Caballano-Infantes.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a highly reactive gas with a brief life span, synthesized by the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS) through L-arginine oxidation to L-citrulline.

- nitric oxide

- stem cell

- evolution

- cell signaling

- cell differentiation

1. Biological Functions of Nitric Oxide

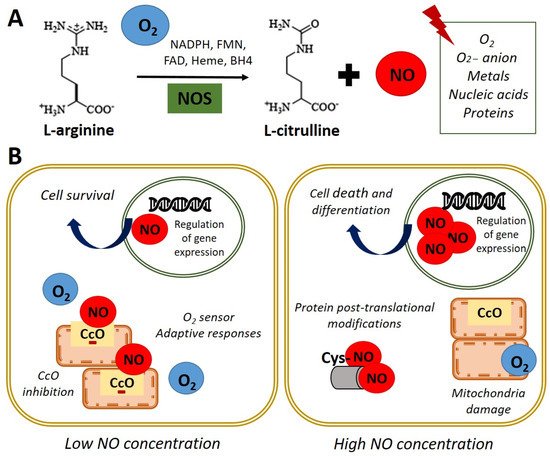

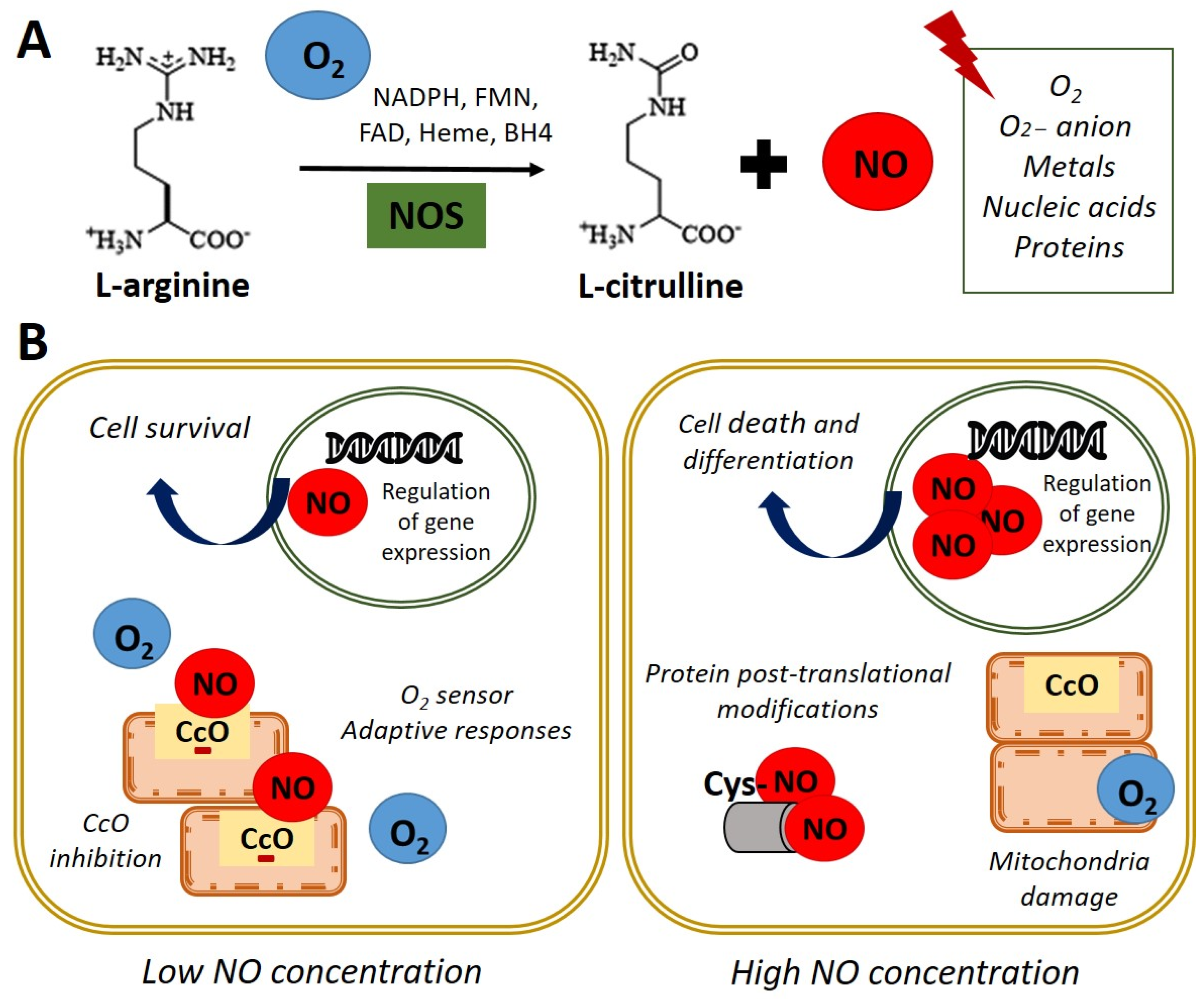

Nitric oxide (NO) is a highly reactive gas with a brief life span, synthesized by the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS) through L-arginine oxidation to L-citrulline. In most mammals, the existence of 3 isoforms of the NOS enzyme has been described: NOS1 (nNOS-neuronal), NOS2 (iNOS-inducible), and NOS3 (eNOS-endothelial) [1]. NO is a free radical that interacts with oxygen (O2), super-oxide anion (O2−), metals, nucleic acids, and proteins (Figure 1A). In turn, NO is rapidly oxidized and transformed into nitrate and nitrite in a reversible reaction catalyzed by reductase enzymes activated when endogenous NOS enzymes are dysfunctional [2,3][2][3].

Figure 1. Nitric oxide synthesis and biological functions. (A) In normoxia conditions (21% O2), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) catalyzes the oxidation of the terminal guanidinyl nitrogen of the amino acid L-arginine to form L-citrulline and nitric oxide (NO) in presence of NADPH and cofactors such as flavin mononucleotide (FMN), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), heme, and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) [3]. Once produced, NO readily interacts with O2, O2− anion, metals, nucleic acids, and proteins. (B) Left panel. NO at low concentration inhibits cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) activity by competing with O2. Adaptive responses to O2 concentration and cell survival genes are activated. Right panel. High concentrations of NO induce damage in all mitochondrial complexes, nitrosylation, or oxidation of protein thiol groups and induce cell death and differentiation.

Figure 1. Nitric oxide synthesis and biological functions. (A) In normoxia conditions (21% O2), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) catalyzes the oxidation of the terminal guanidinyl nitrogen of the amino acid L-arginine to form L-citrulline and nitric oxide (NO) in presence of NADPH and cofactors such as flavin mononucleotide (FMN), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), heme, and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) [3]. Once produced, NO readily interacts with O2, O2− anion, metals, nucleic acids, and proteins. (B) Left panel. NO at low concentration inhibits cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) activity by competing with O2. Adaptive responses to O2 concentration and cell survival genes are activated. Right panel. High concentrations of NO induce damage in all mitochondrial complexes, nitrosylation, or oxidation of protein thiol groups and induce cell death and differentiation.NO acts as an essential second messenger involved in numerous biological functions such as regulating blood pressure, through the relaxation of smooth muscle and the inhibition of platelets aggregation, as well as modulating the immune response and as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system [4]. Furthermore, NO has been shown to affect the expression of genes that regulate cell survival and proliferation, at transcriptional and translational levels, in several cell types [5,6][5][6]. Additionally, NO has a role in the pathophysiology of cancer or endocrine and neurodegenerative diseases [7]. Moreover, NO plays a key role in embryonic development, emphasizing its importance in cardiac development and function [8,9][8][9].

Regarding the functions performed by NO, it has been reported that these are dependent on their intracellular concentration. On the one hand, physiological concentration modulates cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) activity, depending on the intracellular O2 concentration and the redox state of CcO. It was observed in rat lung mitochondria that NO at low concentrations inhibits CcO, competing with O2 [10]. This interaction between CcO and NO allows the detection of changes in O2 concentrations and the initiation of adaptive responses. On the other hand, high doses of NO can induce post-translational modifications through nitrosylation, or oxidation of protein thiol groups and cause the oxidation of iron (Fe2+) of the mitochondrial active centers in rat liver mitochondria, causing damage in all mitochondrial complexes [11]. This evidence indicates that NO could be a physiological regulator of cellular respiration and metabolism (Figure 1B). Furthermore, the potential role of NO in regulating the cellular response to hypoxia in vitro has been described [10,12,13,14][10][12][13][14]. In these studies, the authors used an interval of oxygen pressure value around 1–5% of O2 to induce severe or physiological hypoxic conditions in vitro.

Interestingly, it has been reported the direct effect of NO on processes such as cell proliferation and survival in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [5]. Besides, increased NO concentrations due to an inflammatory response can cause oxidative effects and nitrosative stress with the consequent induction of apoptosis. These effects are implicated in the pathophysiology of degenerative diseases since they are the cause of chronic cell death [15]. Despite the adverse effects described after the accumulation of high concentrations of NO at the intracellular level, the use of pharmacological treatment with high doses of NO in ESCs has been described to induce differentiation towards certain specific cellular lineages (Figure 1B). Thus, the NO donor molecules are essential components in designing controlled differentiation protocols [6,16,17,18][6][16][17][18]. This field is intensely discussed in the current entreviewy and the recent applications of exogenous NO treatments in regenerative medicine.

2. Nitric Oxide Signaling Pathways in Stem Cell

NO exerts its effects through cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent and independent mechanisms [19,20,21][19][20][21]. The independent cGMP pathway is based on NO’s interaction with molecules such as O2, anion O2− and CcO, among others, due to its high reactivity as previously described [10]. The effect of these reactions is different depending on the concentrations of NO. Nitrosylation and nitration reactions are frequent at high doses of NO [22]. Regarding the cGMP-dependent effects, NO activity is mediated through the soluble receptor guanylate cyclase (sGC), which is a heterodimeric hemoprotein composed of the α subunit (sGCα) and the β subunit (sGCβ) [23]. NO activates sGC by interacting with a heme group catalyzing GTP conversion to cGMP. This activation, in turn, triggers the initiation of a signaling cascade that regulates a wide variety of physiological effects upon interaction with proteins such as the cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) family, cGMP-dependent phosphodiesterases, and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNG) in stem cells (SCs) [20]. Thereafter, it was established that the NO/cGMP route could have an essential role in embryonic development [24] and several additional studies have shown different expressions of NO signaling pathway´s effectors in embryonic cells at various stages of differentiation processes [20,25,26,27][20][25][26][27].

In this line, NO/cGMP/PKG signaling in bone enhances osteoblasts’ proliferation, differentiation, and cell survival. Thus, sGC is a potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis [28,29,30][28][29][30]. In this context, it has been reported an increase in mouse ESCs (mESCs) differentiation after treatment with iNOS-loaded mineralized nanoparticles that release NO and increase cGMP intracellular concentration, enhancing osteogenesis-related protein levels [31]. Moreover, this pathway is thought to play a crucial role in mediating vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, and fibrosis in cardiomyocytes [32,33][32][33]. Accordingly, renovation of adequate NO-sGC–cGMP signaling induced by oral sGC stimulators has been proposed as a noteworthy treatment aim in heart failure [34,35][34][35]. Besides, the involvement of NO-signaling in the neuronal differentiation has been assessed. This sentudry revealed that valproic acid (VPA) encourages mature neuronal differentiation of rat adipose tissue-derived SCs through the iNOS–NO–sGC signaling pathway [36]. Additionally, the role of NO enhancing differentiation of mesenchymal SCs (MSCs) to endothelial cells (ECs) has been defined. Bandara et al. reported that NO-producing rat MSCs induce the expression of key endothelial genes while decrease the expression of vascular markers. Moreover, the implantation of a biomaterial scaffold containing NO-producing MSCs enhanced new blood vessels generation, being a novel strategy to vascular regeneration [37].

Alternatively, it has been shown that NO can carry out post-translational modifications such as S-nitrosylation in the cysteine residues of sGC in lung epithelial cells and in Jurkat T cells [38]. In this line, NO’s effects on maintaining pluripotency and differentiation of SCs could also be independent of the sGC-cGMP pathway. In this sense, it was observed an increase in Oct-4 expression in adult mouse bone marrow SCs treated with low dose of NO [39]. However, the mechanisms underlying NO’s effects on SCs stemness are not fully established. Research on NO’s role in SCs fate indicates that this mechanism appears to be independent of the LIF/Stat3 pathway since phosphorylated Stat3 protein levels are not detected in NO-treated ESCs [5]. Moreover, elevated Nanog expression from transgene constructs is sufficient for clonal expansion of ESCs, bypassing Stat3 [40]. Chanda et al. showed that genetic or pharmacological blocking of iNOS decreases DNA accessibility and prevents induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSCs) generation. They elucidated that the effect of NO on DNA accessibility is partially modulated by S-nitrosylation of nuclear proteins, as MTA3 (Metastasis Associated 1 Family Member 3), a subunit of NuRD (nucleosome remodeling deacetylase) complex. Furthermore, this sentudry described that overexpression of mutant MTA3, in which the 2 cysteine residues are replaced by alanine residues, impairs the generation of iPSCs from murine embryonic fibroblasts [41].

3. Nitric Oxide in the Embryonic Development

As mentioned previously, NO plays an essential role in embryonic development, and it has been described that it can act as a negative regulator of cell proliferation during differentiation and organogenesis in Xenopus and Drosophila [42,43][42][43]. Additionally, it has been identified that a critical concentration of NO and cGMP is mandatory for normal mouse embryonic development, and abnormalities from this concentration lead to developmental detention and/or apoptosis of the embryo [44]. This finding claims a key role of NO in embryo development and provides further evidence for the significance of NO generation in murine embryo development and potential in other mammals. Furthermore, NO production is decisive for establishing neural connections in flies, indicating that NO affects the acquisition of differentiated neural tissue [43]. Besides, it was observed that blocking NO production in neural precursor cells in mice resulted in increased cell proliferation [45].

Regarding NO in early development, it is required in cardiomyogenesis processes since it was proven that NOS inhibitors prevent the maturation of cardiomyocytes in ESCs. On the other hand, NOS inhibitors arrest the differentiation of mESCs towards a cardiac phenotype. Thus, NO donors’ treatment can reverse this effect in murine and rat embryos [9]. The expression of the NOS2 and NOS3 isoforms has been reported to occur prominently during the early stages of cardiomyogenesis until it begins to decline around day 14 of embryogenesis [9]. Complementary studies have described that NOS3 expression is increased at early stages and decrease during mESCs differentiation to cardiomyocytes, which suggests that NO could participate in early differentiation events of mESCs and physiological processes in cardiomyocytes [19]. The generation of triply n/i/eNOS (−/−) mice has evidenced the systemic deletion of all three NOSs causes a variety of cardiovascular diseases in mice, demonstrating a critical role of the endogenous NOSs system in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis [46]. These results constitute substantial support establishing NO’s role as a regulator of organogenesis and embryonic development.

Regarding NO’s role in evolution, reproduction, and fertility, the studies show that this molecule is an essential regulator in ovarian steroidogenesis. NOS is expressed in human granulosa-luteal cells and inhibits estradiol secretion independent of cGMP by straight preventing aromatase activity, downregulation of mRNA levels of the enzyme, and an acute, and direct inhibition of the enzyme activity [47,48][47][48]. It has been reported that NO encourages the generation of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and progesterone by human granulosa luteinized cells with minor caspase-3 action hence displaying the role of ANP, progesterone, and NO on the survival of pre-ovulatory human follicle [49]. Additionally, it was described that iNOS and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) mRNAs and proteins levels are meaningfully increased in cumulus cells from oocytes not fertilized as compared with the fertilized oocyte. Moreover, not fertilized oocytes showed an increase in NF-κB pathway. These results highlight the role of iNOS and HO-1 as biomarkers of fertility in order to improve human oocyte selection [50]. Furthermore, NO contributes to placental vascular development and function meanwhile the initial phases of pregnancy. Indeed, NO dynamically controls embryo development, implantation, and trophoblast incursion and is one of the key vasodilators in umbilical and placental vessels [51].

4. Nitric Oxide and Stemness of Pluripotent Cells

Pluripotent SCs (PSCs) display the ability to proliferate even though preserving the capacity to produce diverse cell types throughout tissue growth and renewal [52]. The molecular mechanisms subjacent these properties are being widely studied, given the potential applications of PSCs in cell therapy. Therefore, the analysis of the mechanisms that regulate the maintenance of pluripotency and differentiation has been the focus of study to establish better differentiation strategies towards specific lineages of clinical interest. In turn, understanding these mechanisms can implement the reprogramming processes towards iPSCs. In this sense, identifying small molecules that act on specific cell signaling pathways that participate in embryonic development provides a useful tool in designing protocols that can efficiently control the “stem state” of SCs and differentiation. Concerning this objective, NO has been described as a molecule used in culture media to promote the differentiation of SCs towards different specific lineages, showing evidence that established its role in the control of tissue differentiation and morphogenesis [6,18][6][18]. In general, NO is known for its role as an inducer of apoptosis as was observed in liver cancer cells and in insulin-secreting rat cells [53,54][53][54]. Still, it is important to highlight that the induction of apoptosis and differentiation is dose dependent. Its role as a protector of cell death, at low doses, in certain types of cells, as in ESCs or in hepatocytes, has also been described [5,55][5][55].

Regarding NO’s role as a differentiation inducer, a study by S. Kanno et al. in 2004 [56] described obtaining cardiomyocytes from ESCs after exposure to high concentrations of chemical NO donors. Subsequently, NO can induce proliferation or differentiation of specific cells, but its effect varies widely depending on each cell type and NO intracellular concentration. For example, the proliferation and differentiation of human skin cells are modulated by NO [57]. In this coentext, ourry, researchers group has reported that exposure of ESCs to low concentrations (2–20 μM) of the NO donor diethylenetriamine NO adduct (DETA-NO) confers protection from apoptosis; and these effects were also observed in cells overexpressing eNOS. Moreover, this studentry reported that ESCs exposed to low doses of NO were prevented from the spontaneous differentiation induced by the withdrawal from the cell culture medium of the leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) in murine and of the basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), in human cell lines, respectively. Similarly, weresearchers described that constitutive overexpression of eNOS in cells exposed to LIF deprivation maintained the expression of self-renewal markers, whereas the differentiation genes were repressed [5]. Conversely, ouresearchers' group reported that high doses (0.25–1 mM) of DETA-NO induce differentiation of mESCs by repression of Nanog and Oct-4 and promote expression of early endoderm markers [6]. These findings support the dual role of NO in the control of ESCs self-renewal and differentiation.

4.1. Nitric Oxide and Stem Cell Differentiation

As previously described, wresearchers reported that high concentrations of DETA-NO promote the differentiation of mESCs through the negative regulation of the expression of Nanog and Oct-4. WResearchers showed that Nanog repression by NO is dependent on the activation of p53, through covalent modifications such as the phosphorylation of Ser315 and the acetylation of Lys379. In addition, an increase of cells with epithelial morphology and expression of early endoderm markers such as Pdx1 was revealed. When these cells were exposed to DETA-NO and subsequently, VPA for 6 days, cells with endoderm phenotype and expressing definitive endoderm markers, such as FoxA2, Sox17, Hnf1-β and GATA4, were obtained [6]. WResearchers then deeper studied the mechanisms involved in Pdx1 gene regulation by NO in mESCs. WResearchers showed that, Pdx1 expression induced by NO is linked with the release of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) and the histone acetyl-transferase P300 from its promoter area. These events are accompanied by epigenetic changes in bivalent markers of histones trimethylated (H3K27me3 and H3K4me3), site-specific changes in DNA methylation, and no changes in H3 acetylation [18]. Interestingly, the combined use of small molecules such as DETA-NO, VPA, P300 inhibitor and finally the generation of cell aggregates lead to sequential activation of key signals for pancreatic lineage specification, obtaining cells expressing β-cell markers such as Pdx1, Nkx6.1, GcK, Kir6.2, Glut2, and Ins1 that are capable of responding to secretagogues such as high glucose and KCl [18]. This protocol is pioneer in using NO to direct differentiation programs towards pancreatic lineages.

Several studies show NO-mediated induction of apoptosis in different cell types, including pancreatic beta cells [58,59][58][59] and hepatocytes [60], among others. However, it has been described that a population of ESCs resists nitrosative stress induced by exposure to high levels of NO, and that they increase the expression of cytoprotective genes, such as heme-oxygenase-1 (Hmox1) and Hsp70. Furthermore, it was reported that these cells resistant to stress-induced by high doses of NO enter a process of cell differentiation [6].

Concerning the role of NO as an antiapoptotic agent, it was reported that this mechanism is orchestrated by Bad phosphorylation through PI3K/Akt-dependent activation in insulin-producing rat cells [61].

Regarding cell differentiation signaling pathways induced by NO, it observed the activation of the phospho-inositide-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling after exogenous NO treatment. Remarkably, the use of AKT activator in absence of NO did not promote endothelial differentiation of mESCs, suggesting an interdependent association between NO and the Akt activation [62].

4.2. Nitric Oxide and Pluripotency

Studies carried out in ouresearchers' laboratory have shown that low doses of DETA-NO (2–20 μmol/L) delay human ESCs (hESCs) differentiation since the addition of NO induces an increase in the expression of Nanog, Oct-4, and Sox2. Furthermore, the expression of the SSEA-4 cell surface antigen characteristic of hESC, which disappears five passages after removal of bFGF, is preserved when the culture medium is supplemented with NO. In addition, it was reported that NO at low doses represses some differentiation markers (Brachyury, Gata4, Gata6, Fgf5, and Fgf8), which are expressed when bFGF is removed from the culture medium. Similar results were obtained for mESC lines cultured in the absence of LIF and supplemented with NO. This sentudry also reported that constitutive overexpression of NOS3 in cultured cells in the absence of LIF protected these cells from apoptosis and promoted cell survival [5]. Furthemore, it was later described that the culture of mESCs with low dose of NO (2 μM DETA-NO) without LIF in the culture media, promoted substantial modifications in the expression of 16 genes involved in the regulation of the pluripotency state. Additionally, the treatment with DETA-NO induced a high level of binding of active H3K4me3 in the Oct-4 and Nanog promoters and H3K9me3 and H3k27me3 in the Brachyury promoter. Moreover, it was observed the activation of pluripotency pathways, such as Gsk3-β/β-catenin, in addition to PI3K/AKT activation, which supports the protective effect of NO at low doses against apoptosis. Finally, mESC proliferation decreased, coinciding with the arrest of the cell cycle in the G2/M phase [63]. These results suggested that NO was necessary but not sufficient for maintaining pluripotency and preventing cell differentiation of mESCs.

Numerous studies have reported that NO prevents apoptosis in mESCs by regulating the expression of proteins of the Bcl2 family [5,64][5][64]. Increased expression of Bcl2 has been observed in long-term cultured mESCs cultures in an undifferentiated state that maintains their differentiation potential [65]. In the same line, overexpression of the porcine BCL2 gene significantly promotes porcine iPSCs survival without compromising their pluripotency [66].

At low levels, NO provides resistance to tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) produced by hepatotoxicity in rat hepatocytes [67] and inhibits apoptosis in B lymphocytes induced by Fas [68]. Similarly, it has been reported that low concentrations of NO protect bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) from spontaneous apoptosis [69].

In studies carried out by ouresearchers' group, it has been shown that low levels of NO-induced NOS3 overexpression increase the survival of pancreatic beta cells through IGF-1 activation and insulin-induced survival pathways [16]. OuResearchers' group has also described that exposure to DETA-NO (2–20 μmol/L) protects ESCs from apoptosis through processes that include the decrease of Caspase-3, combined with the degradation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. A reduction in the expression of pro-apoptotic genes, Casp7, Casp9, Bax, and Bak1; and an increase in anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl-2 and Birc6 was observed [5]. Additionally, the genomic studies present evidence about the regulation of apoptosis, survival, and response to hypoxia by low doses of NO in mESC. These studies showed the repression of genes involved in the degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor, HIF-1α, the main regulator of the response to hypoxia, together with the overexpression of genes involved in glycolytic metabolism [63]. Considering these preliminary results, wresearchers proposed low doses of NO under normoxic conditions could activate a response similar to hypoxia; and that this activation may be responsible for the mechanism by which NO promotes pluripotency and delays differentiation into ESCs and iPSCs. In this line, weresearchers recently described the essential role of NO inducing a cellular response to hypoxia in PSCs [14].