Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Amina Yu and Version 2 by Alessandra Carrubba.

Milk thistle (Silybum marianum(L.) Gaertn.) is a multipurpose crop suitable to Mediterranean environments.

- alternative crops

- bioactive compounds

- low-input management

- milk thistle

- silymarin

1. Introduction

Milk thistle (Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn.) is a spiny herb belonging to the Asteraceae family. When growing in wild conditions, the plant spends its first season after seed germination at the vegetative stage, therefore being commonly classified as a biennial [1]. Under cultivation, it is mostly grown as an annual crop, with varying cycle durations according to the sowing time [2,3][2][3]. The plant, originally grown in Southern Europe and Asia, is now found throughout the world [4]. Milk thistle has been used for medicinal purposes for over 2000 years, most commonly for the treatment of liver disease (cirrhosis and hepatitis) as well as for the protection of the liver from toxic substances [5,6,7,8][5][6][7][8]. The therapeutic effects of milk thistle are closely connected to the presence of a flavonoid complex called silymarin, composed of a mixture of silybin A and B, isosilybin A and B, silychristin, and silydianin [9,10][9][10]. The highest amount of silymarin is present within the achenes (improperly but commonly termed “seeds”) of the plant [11,12,13][11][12][13]; however, the whole plant is also used for medicinal purposes to treat kidney, spleen, liver, and gallbladder diseases [12,14,15][12][14][15].

In the last decade, research into the use of silymarin expanded considerably, embracing the possibility of curing other illnesses and ailments. In addition to its hepato-protective effect [16], silymarin also showed antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic properties [17]. It was found to stimulate protein biosynthesis, to increase lactation, and to possess immune-modulatory activity [18]. Furthermore, silymarin inhibits cell growth, DNA synthesis, and other mitogenic signals in human prostate, breast, and cervical carcinoma cells [19,20][19][20].

It was introduced as a crop in most areas of Europe, Asia, North and South America, and Southern Australia [21,22][21][22]. In Poland, which is an important European producer of milk thistle seeds and its derivates, the cultivated area covers about 2000 ha [23]. Its commercial cultivation has recently become more significant in North America [24], where milk thistle is among the top-selling herbal dietary supplements, with retail sales amounting to USD 2.6 million in the mainstream multioutlet channel in 2015 [25]. Likewise, in Italy, milk thistle stands as one of the major cultivated or cultivable medicinal species, ranking fourth for volume used (1,920,000 kg/year), and fifth for its estimated wholesale commercial value (EUR 3,494,400 per year) [26].

In Mediterranean environments, exploratory studiones agree in considering milk thistle as one of the most interesting alternative crops, even for marginal environments [3,27,28][3][27][28].

However, in some areas, the plant is considered a noxious weed and treated consequently. In Pakistan, wheat yield losses caused by S. marianum infestation ranged from 7% to 37% [29]. In pastures, it is considered a dangerous, invasive species since its large rosette (up to 1 m in diameter) has the potential to displace most other pasture species, and its spiny thistles can hinder the movement and grazing activity of livestock. Additionally, due to the plant’s ability to accumulate nitrogen, some cases of livestock intoxication after milk thistle ingestion have been reported, especially when the ingested plant was in the early wilting stage [29,30,31][29][30][31].

2. Origin and Distribution

Milk thistle is native to the Mediterranean basin, within a large area spanning from southern Europe to Asia Minor and northern Africa, although it is also naturalized in other continents [14,32,33,34][14][32][33][34]. It is a typical species of the Mediterranean-Turanic chorotype [32]. In Italy, it is spread all over the country, between 0 and 1100 m asl, with the exception of Friuli, most of the Po Valley, and the Alps [1].

Milk thistle has long been known as a useful species. Indeed, archeological surveys have demonstrated its utilization since the Neolithic Era in the Mediterranean environment [35]. Seeds of milk thistle have been used for medicinal purposes for more than 2000 years, mostly to treat liver diseases [36]. Theophrastus (4th century BC) was probably the first one to describe it, under the name “Pternix”; later, the plant was mentioned by Dioscorides in his “Materia Medica” (1st century AD) and by Plinius the Elder (1st century AD).

The plant is now widespread throughout the world [37], both in wild populations [38] and as a crop [21], usually cultivated to extract silymarin.

In natural conditions, milk thistle, commonly referred to as a ruderal species, can be found in fertile, highly disturbed environments (for e.g.xample, pastures or sheep camps endowed with high soil nitrogen levels), but also in anthropized sites such as roadsides [30]. From natural stands, it spreads easily to cultivated fields, facilitated by its remarkable seed production, easy wind dispersal, and viability. Seeds buried in the soil can remain viable for 3–4 years [39], or even up to 9 years [31]. Hence, plants of S. marianum can be very aggressive and competitive with crops in many cultivated areas, and the species is reported to be a noxious weed [30] on arable land, both in warmer climates (where temperatures rarely fall below 0 °C) [29,40][29][40] and in colder regions [41].

3. Genetics and Breeding

The genus Silybum (Asteraceae) includes two species: S. marianum (L.) Gaertn. and S. eburneum Coss. and Durieu [42,43][42][43]. Hetz et al. [44] argued that the two forms are probably only variants of the same species due to the easy cross-pollination and interfertility occurring between the two genotypes. The same Authors also reported that in crossing experiments between S. marianum and S. eburneum, the number of fruits produced was relatively high as compared to the two parental species. S. marianum is a diploid species (2n = 34) [42], and even though its flowers are often visited by pollinating insects, it was described to be autogamous, with an average outcrossing rate of 2% under field conditions [44].

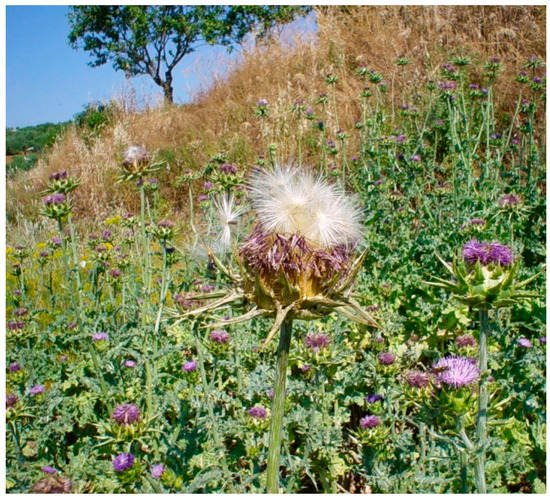

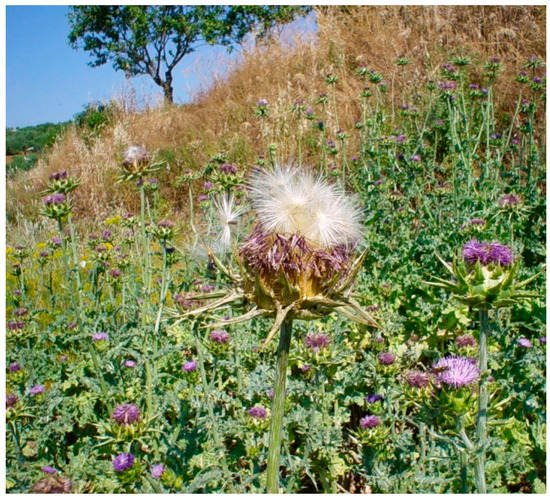

Despite the increasing interest in this species as a multipurpose crop and its actual economic importance in the herbal market, the plant has not been subjected to a thorough breeding activity so far. Limited genetic research has been carried out only since the early 2000s, mainly to develop high-yielding cultivars with elevated silymarin content [45]. Hence, with the lack of specific breeding that addresses agronomical issues, cultivated plants are still in possession of several plant traits that are typical of undomesticated species, including fruit dispersal at maturity (Figure 1), asynchronous flowering, spiny leaves, and erratic outcomes of yield quality and stability. These features are not uncommon in Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs) [46], and in many cases, they are supposed to be developed through the plant’s evolutionary process to ensure the best reproductive success and environmental fitting for them. However, they represent a severe constraint on proper agronomical practice, and a straightforward breeding activity needs to be carried out.

Figure 1.

Fruit shattering at maturity of

Silybum marianum

(Photo: A. Carrubba).

The identification of key genes involved in fruit shattering and the identification of shatter-resistant genotypes were performed by Martinelli [47], who elucidated the physiological basis of shattering and found it to be controlled by air relative humidity, with a substantial influence of the fruit linkage to the receptacle and the conformation of the fruit pappus. In line with this research outcome, this author identified tt, it was three vigorous and stable lines as well as discussed the consequent modifications of biomass composition, plant structure, and habit [47].

Asynchronous flowering is the other major problem with the milk thistle crop. Indeed, at the time of harvest, the plants bear flower heads at all stages of development, with inherent problems for proper crop management, including mechanized harvest [33]. To cope with this issue, the cultivar “Argintiu” was developed in the Republic of Moldova, characterized by simultaneous seed maturation in flower heads [48]. Furthermore, breeding efforts have been addressed in order to obtain plants with a reduced number of secondary flower heads [3].

The issue of the milk thistle’s spiny habit was addressed in Pakistan in the late 1980s, but the attempt to obtain spineless mutants using radiation is still ongoing [49].

Other goals of breeding are concerned with the qualitative aspect of fruits, especially the silymarin content. The discovery of genes involved in the biosynthesis and accumulation of silymarin in fruits integument during development [50[50][51][52][53],51,52,53], or genes implicated in the synthesis of other valuable constituents of the fruits [45], are interesting starting points in this direction. So far, only a few improved cultivars for silymarin production have been registered such as the Polish variety “Silma” [54]. The path to genetic improvement and the breeding of milk thistle is still open, and there is room for the selection of more suitable, productive, and metabolite-rich milk thistle cultivars. Wild populations include genotypes that are supposed to represent the maximum expression of this capability to adapt to environmental conditions [3], hence constituting a valuable gene pool for the further exploitation of this species. A thorough investigation of the amount of variability in wild genotypes, obtained from different geographical regions, is therefore recommended [55].