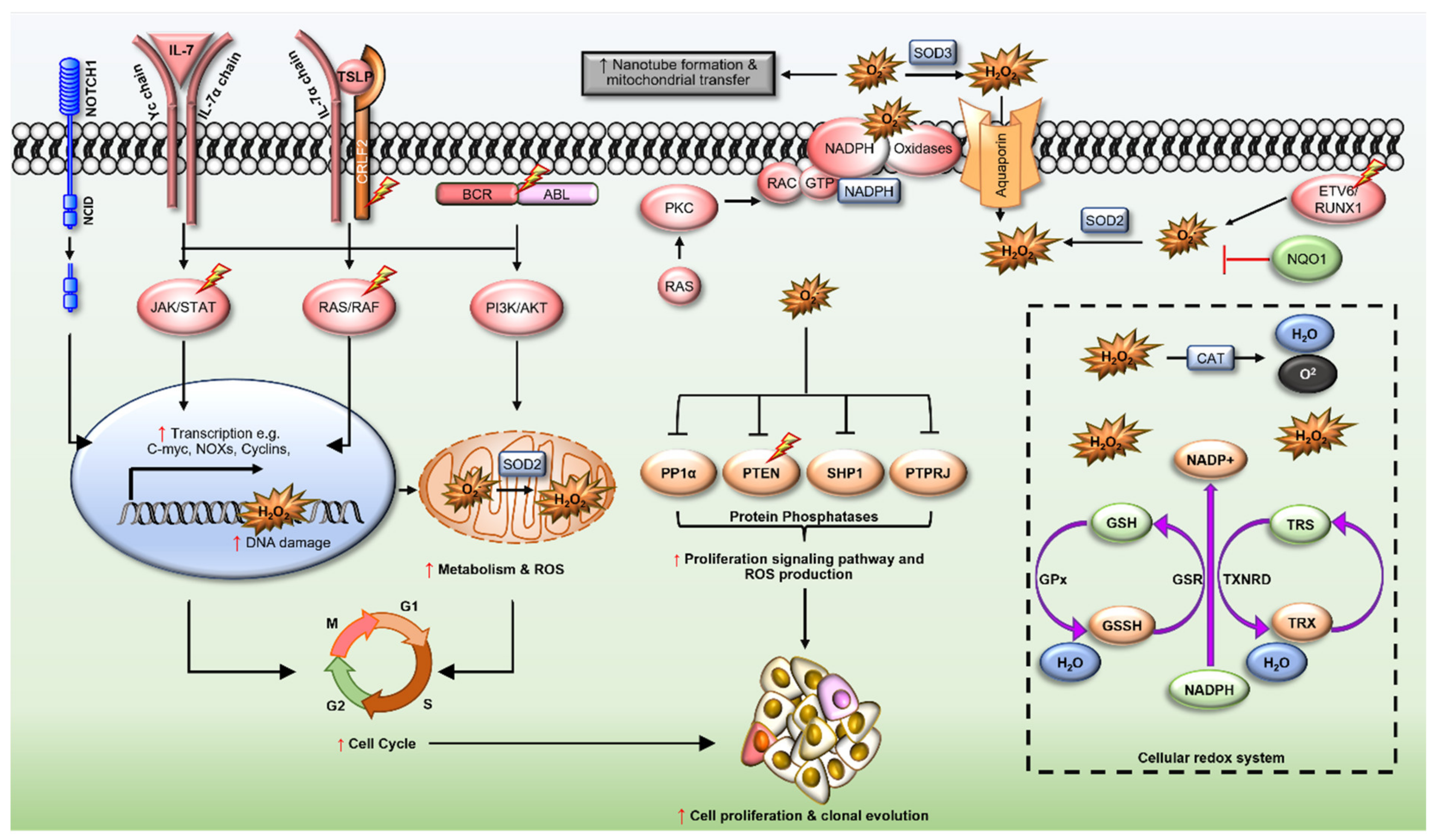

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is the most common cancer diagnosed in children and adolescents. Approximately 70% of patients survive >5-years following diagnosis, however, for those that fail upfront therapies, survival is poor. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are elevated in a range of cancers and are emerging as significant contributors to the leukaemogenesis of ALL. ROS modulate the function of signalling proteins through oxidation of cysteine residues, as well as promote genomic instability by damaging DNA, to promote chemotherapy resistance. Current therapeutic approaches exploit the pro-oxidant intracellular environment of malignant B and T lymphoblasts to cause irreversible DNA damage and cell death, however these strategies impact normal haematopoiesis and lead to long lasting side-effects. Therapies suppressing ROS production, especially those targeting ROS producing enzymes such as the NADPH oxidases (NOXs), are emerging alternatives to treat cancers and may be exploited to improve the ALL treatment.

- acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

- reactive oxygen species

- oxidative stress

- NADPH oxidases

- antioxidants

- redox homeostasis

- second messenger signalling

- oxidative DNA damage

- resistance

- oncogenic signalling

- cysteine oxidation

- kinase

- phosphatase

1. Introduction

2. Redox Dysregulation in ALL

2.1. ETV6/RUNX1 Fusions

2.1. ETV6/RUNX1 Fusions

2.2. BCR/ABL Oncogene

2.2. BCR/ABL Oncogene

2.3. Cytokine Receptor-like Factor 2 (CRLF2)

2.3. Cytokine Receptor-like Factor 2 (CRLF2)

2.4. Interleukin-7 Receptor α (IL7R)

2.5. Transcription Factors PU.1 (SPI1) and Spi-B (SPIB)

2.4. Interleukin-7 Receptor α (IL7R)

2.5. Transcription Factors PU.1 (SPI1) and Spi-B (SPIB)

2.6. Neurogenic Locus Notch Homolog Protein 1 (NOTCH1)

2.6. Neurogenic Locus Notch Homolog Protein 1 (NOTCH1)

2.7. Ras GTPases (N- and KRAS)

2.7. Ras GTPases (N- and KRAS)

2.8. Rho-Family GTPases

2.9. NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1)

2.8. Rho-Family GTPases

2.9. NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1)

3. Redox Homeostasis in ALL

References

- Terwilliger, T.; Abdul-Hay, M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017, 7, e577.

- Ward, E.; DeSantis, C.; Robbins, A.; Kohler, B.; Jemal, A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA 2014, 64, 83–103.

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (ALL). Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/about/key-statistics.html#references (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Hunger, S.P.; Mullighan Charles, G. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1541–1552.

- Bostrom, B.C.; Sensel, M.R.; Sather, H.N.; Gaynon, P.S.; La, M.K.; Johnston, K.; Erdmann, G.R.; Gold, S.; Heerema, N.A.; Hutchinson, R.J.; et al. Dexamethasone versus prednisone and daily oral versus weekly intravenous mercaptopurine for patients with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Blood 2003, 101, 3809–3817.

- Kidd, J.G. Regression of transplanted lymphomas induced in vivo by means of normal guinea pig serum. II. Studies on the nature of the active serum constituent: Histological mechanism of the regression: Tests for effects of guinea pig serum on lymphoma cells in vitro: Discussion. J. Exp. Med. 1953, 98, 583–606.

- Escherich, G.; Zimmermann, M.; Janka-Schaub, G.; CoALL Study Group. Doxorubicin or daunorubicin given upfront in a therapeutic window are equally effective in children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A randomized comparison in trial CoALL 07-03. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 254–257.

- Nguyen, K.; Devidas, M.; Cheng, S.C.; La, M.; Raetz, E.A.; Carroll, W.L.; Winick, N.J.; Hunger, S.P.; Gaynon, P.S.; Loh, M.L.; et al. Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Children’s Oncology Group study. Leukemia 2008, 22, 2142–2150.

- Oriol, A.; Vives, S.; Hernández-Rivas, J.-M.; Tormo, M.; Heras, I.; Rivas, C.; Bethencourt, C.; Moscardó, F.; Bueno, J.; Grande, C.; et al. Outcome after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adult patients included in four consecutive risk-adapted trials by the PETHEMA Study Group. Haematologica 2010, 95, 589–596.

- Board, P.P.T.E. PDQ Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment. In Bethesda; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021.

- Inaba, H.; Mullighan, C.G. Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2524–2539.

- Mullighan, C.G.; Miller, C.B.; Radtke, I.; Phillips, L.A.; Dalton, J.; Ma, J.; White, D.; Hughes, T.P.; Le Beau, M.M.; Pui, C.H.; et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature 2008, 453, 110–114.

- Kontro, M.; Kuusanmaki, H.; Eldfors, S.; Burmeister, T.; Andersson, E.I.; Bruserud, O.; Brummendorf, T.H.; Edgren, H.; Gjertsen, B.T.; Itala-Remes, M.; et al. Novel activating STAT5B mutations as putative drivers of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1738–1742.

- Holmfeldt, L.; Wei, L.; Diaz-Flores, E.; Walsh, M.; Zhang, J.; Ding, L.; Payne-Turner, D.; Churchman, M.; Andersson, A.; Chen, S.C.; et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 242–252.

- Liu, Y.; Easton, J.; Shao, Y.; Maciaszek, J.; Wang, Z.; Wilkinson, M.R.; McCastlain, K.; Edmonson, M.; Pounds, S.B.; Shi, L.; et al. The genomic landscape of pediatric and young adult T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1211–1218.

- Weng, A.P.; Ferrando, A.A.; Lee, W.; Morris, J.P.t.; Silverman, L.B.; Sanchez-Irizarry, C.; Blacklow, S.C.; Look, A.T.; Aster, J.C. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science 2004, 306, 269–271.

- Palomero, T.; Sulis, M.L.; Cortina, M.; Real, P.J.; Barnes, K.; Ciofani, M.; Caparros, E.; Buteau, J.; Brown, K.; Perkins, S.L.; et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1203–1210.

- Kharas, M.G.; Janes, M.R.; Scarfone, V.M.; Lilly, M.B.; Knight, Z.A.; Shokat, K.M.; Fruman, D.A. Ablation of PI3K blocks BCR-ABL leukemogenesis in mice, and a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor prevents expansion of human BCR-ABL+ leukemia cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 3038–3050.

- Yamamoto, T.; Isomura, M.; Xu, Y.; Liang, J.; Yagasaki, H.; Kamachi, Y.; Kudo, K.; Kiyoi, H.; Naoe, T.; Kojma, S. PTPN11, RAS and FLT3 mutations in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2006, 30, 1085–1089.

- Armstrong, S.A.; Mabon, M.E.; Silverman, L.B.; Li, A.; Gribben, J.G.; Fox, E.A.; Sallan, S.E.; Korsmeyer, S.J. FLT3 mutations in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2004, 103, 3544–3546.

- Degryse, S.; de Bock, C.E.; Demeyer, S.; Govaerts, I.; Bornschein, S.; Verbeke, D.; Jacobs, K.; Binos, S.; Skerrett-Byrne, D.A.; Murray, H.C.; et al. Mutant JAK3 phosphoproteomic profiling predicts synergism between JAK3 inhibitors and MEK/BCL2 inhibitors for the treatment of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2018, 32, 788–800.

- Den Boer, M.L.; van Slegtenhorst, M.; De Menezes, R.X.; Cheok, M.H.; Buijs-Gladdines, J.G.; Peters, S.T.; Van Zutven, L.J.; Beverloo, H.B.; Van der Spek, P.J.; Escherich, G.; et al. A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: A genome-wide classification study. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 125–134.

- Paulsson, K.; Lilljebjorn, H.; Biloglav, A.; Olsson, L.; Rissler, M.; Castor, A.; Barbany, G.; Fogelstrand, L.; Nordgren, A.; Sjogren, H.; et al. The genomic landscape of high hyperdiploid childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 672–676.

- Neri, A.; Knowles, D.M.; Greco, A.; McCormick, F.; Dalla-Favera, R. Analysis of RAS oncogene mutations in human lymphoid malignancies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 9268–9272.

- Sillar, J.R.; Germon, Z.P.; DeIuliis, G.N.; Dun, M.D. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6003.

- Alvarez, Y.; Coll, M.D.; Ortega, J.J.; Bastida, P.; Dastugue, N.; Robert, A.; Cervera, J.; Verdeguer, A.; Tasso, M.; Aventin, A.; et al. Genetic abnormalities associated with the t(12;21) and their impact in the outcome of 56 patients with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2005, 162, 21–29.

- Sood, R.; Kamikubo, Y.; Liu, P. Role of RUNX1 in hematological malignancies. Blood 2017, 129, 2070–2082.

- Wray, J.P.; Deltcheva, E.M.; Boiers, C.; Richardson, S.E.; Chettri, J.B.; Gagrica, S.; Guo, Y.; Illendula, A.; Martens, J.H.A.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; et al. Cell cycle corruption in a preleukemic ETV6-RUNX1 model exposes RUNX1 addiction as a therapeutic target in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. bioRxiv 2020.

- Kantner, H.-P.; Warsch, W.; Delogu, A.; Bauer, E.; Esterbauer, H.; Casanova, E.; Sexl, V.; Stoiber, D. ETV6/RUNX1 Induces Reactive Oxygen Species and Drives the Accumulation of DNA Damage in B Cells. Neoplasia 2013, 15, 1292-IN1228.

- Schröder, K.; Kohnen, A.; Aicher, A.; Liehn, E.A.; Büchse, T.; Stein, S.; Weber, C.; Dimmeler, S.; Brandes, R.P. NADPH Oxidase Nox2 Is Required for Hypoxia-Induced Mobilization of Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 537–544.

- Sallmyr, A.; Fan, J.; Rassool, F.V. Genomic instability in myeloid malignancies: Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) and error-prone repair. Cancer Lett. 2008, 270, 1–9.

- Teachey, D.T.; Pui, C.-H. Comparative features and outcomes between paediatric T-cell and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e142–e154.

- Kuan, J.W.; Su, A.T.; Leong, C.F.; Osato, M.; Sashida, G. Systematic Review of Normal Subjects Harbouring BCR-ABL1 Fusion Gene. Acta Haematol. 2020, 143, 96–111.

- Cilloni, D.; Saglio, G. Molecular Pathways: BCR-ABL. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 930.

- Koundouros, N.; Poulogiannis, G. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Signaling and Redox Metabolism in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 160.

- Sattler, M.; Verma, S.; Shrikhande, G.; Byrne, C.H.; Pride, Y.B.; Winkler, T.; Greenfield, E.A.; Salgia, R.; Griffin, J.D. The BCR/ABL Tyrosine Kinase Induces Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in Hematopoietic Cells*. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 24273–24278.

- Koptyra, M.; Falinski, R.; Nowicki, M.O.; Stoklosa, T.; Majsterek, I.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Blasiak, J.; Skorski, T. BCR/ABL kinase induces self-mutagenesis via reactive oxygen species to encode imatinib resistance. Blood 2006, 108, 319–327.

- Naughton, R.; Quiney, C.; Turner, S.D.; Cotter, T.G. Bcr-Abl-mediated redox regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Leukemia 2009, 23, 1432–1440.

- Landry, W.D.; Woolley, J.F.; Cotter, T.G. Imatinib and Nilotinib inhibit Bcr–Abl-induced ROS through targeted degradation of the NADPH oxidase subunit p22phox. Leuk. Res. 2013, 37, 183–189.

- Cho, Y.J.; Zhang, B.; Kaartinen, V.; Haataja, L.; Curtis, I.d.; Groffen, J.; Heisterkamp, N. Generation of rac3 Null Mutant Mice: Role of Rac3 in Bcr/Abl-Caused Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 5777–5785.

- Miyano, K.; Koga, H.; Minakami, R.; Sumimoto, H. The insert region of the Rac GTPases is dispensable for activation of superoxide-producing NADPH oxidases. Biochem. J. 2009, 422, 373–382.

- Koptyra, M.; Cramer, K.; Slupianek, A.; Richardson, C.; Skorski, T. BCR/ABL promotes accumulation of chromosomal aberrations induced by oxidative and genotoxic stress. Leukemia 2008, 22, 1969–1972.

- Deutsch, E.; Dugray, A.; AbdulKarim, B.; Marangoni, E.; Maggiorella, L.; Vaganay, S.; M’Kacher, R.; Rasy, S.D.; Eschwege, F.O.; Vainchenker, W.; et al. BCR-ABL down-regulates the DNA repair protein DNA-PKcs. Blood 2001, 97, 2084–2090.

- Slupianek, A.; Nowicki, M.O.; Koptyra, M.; Skorski, T. BCR/ABL modifies the kinetics and fidelity of DNA double-strand breaks repair in hematopoietic cells. DNA Repair 2006, 5, 243–250.

- Slupianek, A.; Schmutte, C.; Tombline, G.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Hoser, G.; Nowicki, M.O.; Pierce, A.J.; Fishel, R.; Skorski, T. BCR/ABL Regulates Mammalian RecA Homologs, Resulting in Drug Resistance. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 795–806.

- Staudt, D.; Murray, H.C.; McLachlan, T.; Alvaro, F.; Enjeti, A.K.; Verrills, N.M.; Dun, M.D. Targeting Oncogenic Signaling in Mutant FLT3 Acute Myeloid Leukemia: The Path to Least Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3198.

- Murray, H.C.; Enjeti, A.K.; Kahl, R.G.S.; Flanagan, H.M.; Sillar, J.; Skerrett-Byrne, D.A.; Al Mazi, J.G.; Au, G.G.; de Bock, C.E.; Evans, K.; et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics uncovers synergy between DNA-PK and FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1782–1787.

- Al-Shami, A.; Spolski, R.; Kelly, J.; Fry, T.; Schwartzberg, P.L.; Pandey, A.; Mackall, C.L.; Leonard, W.J. A role for thymic stromal lymphopoietin in CD4(+) T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200, 159–168.

- Russell, L.J.; Capasso, M.; Vater, I.; Akasaka, T.; Bernard, O.A.; Calasanz, M.J.; Chandrasekaran, T.; Chapiro, E.; Gesk, S.; Griffiths, M.; et al. Deregulated expression of cytokine receptor gene, CRLF2, is involved in lymphoid transformation in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2009, 114, 2688–2698.

- Jain, N.; Roberts, K.G.; Jabbour, E.; Patel, K.; Eterovic, A.K.; Chen, K.; Zweidler-McKay, P.; Lu, X.; Fawcett, G.; Wang, S.A.; et al. Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A high-risk subtype in adults. Blood 2017, 129, 572–581.

- Roberts, K.G.; Pei, D.; Campana, D.; Payne-Turner, D.; Li, Y.; Cheng, C.; Sandlund, J.T.; Jeha, S.; Easton, J.; Becksfort, J.; et al. Outcomes of children with BCR-ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with risk-directed therapy based on the levels of minimal residual disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3012–3020.

- Akada, H.; Akada, S.; Hutchison, R.E.; Sakamoto, K.; Wagner, K.-U.; Mohi, G. Critical Role of Jak2 in the Maintenance and Function of Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Stem. Cells 2014, 32, 1878–1889.

- Tasian, S.K.; Doral, M.Y.; Borowitz, M.J.; Wood, B.L.; Chen, I.M.; Harvey, R.C.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Willman, C.L.; Hunger, S.P.; Mullighan, C.G.; et al. Aberrant STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathway signaling occurs in human CRLF2-rearranged B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2012, 120, 833–842.

- Hertzberg, L.; Vendramini, E.; Ganmore, I.; Cazzaniga, G.; Schmitz, M.; Chalker, J.; Shiloh, R.; Iacobucci, I.; Shochat, C.; Zeligson, S.; et al. Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a highly heterogeneous disease in which aberrant expression of CRLF2 is associated with mutated JAK2: A report from the International BFM Study Group. Blood 2010, 115, 1006–1017.

- Mullighan, C.G. The molecular genetic makeup of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology 2012, 2012, 389–396.

- Yoda, A.; Yoda, Y.; Chiaretti, S.; Bar-Natan, M.; Mani, K.; Rodig, S.J.; West, N.; Xiao, Y.; Brown, J.R.; Mitsiades, C.; et al. Functional screening identifies CRLF2 in precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 252–257.

- Shochat, C.; Tal, N.; Bandapalli, O.R.; Palmi, C.; Ganmore, I.; te Kronnie, G.; Cario, G.; Cazzaniga, G.; Kulozik, A.E.; Stanulla, M.; et al. Gain-of-function mutations in interleukin-7 receptor-alpha (IL7R) in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 901–908.

- Rochman, Y.; Kashyap, M.; Robinson, G.W.; Sakamoto, K.; Gomez-Rodriguez, J.; Wagner, K.-U.; Leonard, W.J. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-mediated STAT5 phosphorylation via kinases JAK1 and JAK2 reveals a key difference from IL-7–induced signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19455–19460.

- Silva, A.; Gírio, A.; Cebola, I.; Santos, C.I.; Antunes, F.; Barata, J.T. Intracellular reactive oxygen species are essential for PI3K/Akt/mTOR-dependent IL-7-mediated viability of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia 2011, 25, 960–967.

- Van Der Zwet, J.C.G.; Buijs-Gladdines, J.G.C.A.M.; Cordo, V.; Debets, D.; Smits, W.K.; Chen, Z.; Dylus, J.; Zaman, G.; Altelaar, M.; Oshima, K.; et al. The Central Role of MAPK-ERK Signaling in IL7-Dependent and IL7-Independent Steroid Resistance Reveals a Broad Application of MEK-Inhibitors Compared to JAK1/2-Inhibition in T-ALL. Blood 2020, 136, 20.

- Polli, M.; Dakic, A.; Light, A.; Wu, L.; Tarlinton, D.M.; Nutt, S.L. The development of Funct. B lymphocytes in conditional PU.1 knock-out mice. Blood 2005, 106, 2083–2090.

- Su, G.H.; Chen, H.-M.; Muthusamy, N.; Garrett-Sinha, L.A.; Baunoch, D.; Tenen, D.G.; Simon, M.C. Defective B cell receptor-mediated responses in mice lacking the Ets protein, Spi-B. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 7118–7129.

- Marty, C.; Lacout, C.; Droin, N.; Le Couédic, J.P.; Ribrag, V.; Solary, E.; Vainchenker, W.; Villeval, J.L.; Plo, I. A role for reactive oxygen species in JAK2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm progression. Leukemia 2013, 27, 2187–2195.

- Lim, M.; Batista, C.R.; Oliveira, B.R.d.; Creighton, R.; Ferguson, J.; Clemmer, K.; Knight, D.; Iansavitchous, J.; Mahmood, D.; Avino, M.; et al. Janus Kinase Mutations in Mice Lacking PU.1 and Spi-B Drive B Cell Leukemia through Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced DNA Damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 40, e00189-20.

- Staber, P.B.; Zhang, P.; Ye, M.; Welner, R.S.; Nombela-Arrieta, C.; Bach, C.; Kerenyi, M.; Bartholdy, B.A.; Zhang, H.; Alberich-Jordà, M.; et al. Sustained PU.1 Levels Balance Cell-Cycle Regulators to Prevent Exhaustion of Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 934–946.

- Manea, A.; Manea, S.A.; Gafencu, A.V.; Raicu, M.; Simionescu, M. AP-1-dependent transcriptional regulation of NADPH oxidase in human aortic smooth muscle cells: Role of p22phox subunit. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 878–885.

- Sanchez-Martin, M.; Ferrando, A. The NOTCH1-MYC highway toward T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2017, 129, 1124–1133.

- Vafa, O.; Wade, M.; Kern, S.; Beeche, M.; Pandita, T.K.; Hampton, G.M.; Wahl, G.M. c-Myc Can Induce DNA Damage, Increase Reactive Oxygen Species, and Mitigate p53 Function: A Mechanism for Oncogene-Induced Genetic Instability. Mol. Cell 2002, 9, 1031–1044.

- Silva, A.; Yunes, J.A.; Cardoso, B.A.; Martins, L.R.; Jotta, P.Y.; Abecasis, M.; Nowill, A.E.; Leslie, N.R.; Cardoso, A.A.; Barata, J.T. PTEN posttranslational inactivation and hyperactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway sustain primary T cell leukemia viability. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 3762–3774.

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Qian, X.; Gao, S.; Xia, J.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Man, J.; Zhai, X. Genetic mutational analysis of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia from a single center in China using exon sequencing. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 211.

- Jerchel, I.S.; Hoogkamer, A.Q.; Ariës, I.M.; Steeghs, E.M.P.; Boer, J.M.; Besselink, N.J.M.; Boeree, A.; van de Ven, C.; de Groot-Kruseman, H.A.; de Haas, V.; et al. RAS pathway mutations as a predictive biomarker for treatment adaptation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2018, 32, 931–940.

- Tang, C.; Li, M.-H.; Chen, Y.-L.; Sun, H.-Y.; Liu, S.-L.; Zheng, W.-W.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Li, H.; Fu, W.; Zhang, W.-J.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced niche perturbs hematopoietic reconstitution in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 204.

- Irving, J.; Matheson, E.; Minto, L.; Blair, H.; Case, M.; Halsey, C.; Swidenbank, I.; Ponthan, F.; Kirschner-Schwabe, R.; Groeneveld-Krentz, S.; et al. Ras pathway mutations are prevalent in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and confer sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Blood 2014, 124, 3420–3430.

- Ksionda, O.; Melton, A.A.; Bache, J.; Tenhagen, M.; Bakker, J.; Harvey, R.; Winter, S.S.; Rubio, I.; Roose, J.P. RasGRP1 overexpression in T-ALL increases basal nucleotide exchange on Ras rendering the Ras/PI3K/Akt pathway responsive to protumorigenic cytokines. Oncogene 2016, 35, 3658–3668.

- Mues, M.; Roose, J.P. Distinct oncogenic Ras signals characterized by profound differences in flux through the RasGDP/RasGTP cycle. Small GTPases 2017, 8, 20–25.

- Hole, P.S.; Pearn, L.; Tonks, A.J.; James, P.E.; Burnett, A.K.; Darley, R.L.; Tonks, A. Ras-induced reactive oxygen species promote growth factor–independent proliferation in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood 2010, 115, 1238–1246.

- Molina, J.R.; Adjei, A.A. The Ras/Raf/MAPK Pathway. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2006, 1, 7–9.

- Fernández-Medarde, A.; Santos, E. Ras in cancer and developmental diseases. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 344–358.

- Kerstjens, M.; Driessen, E.M.C.; Willekes, M.; Pinhanços, S.S.; Schneider, P.; Pieters, R.; Stam, R.W. MEK inhibition is a promising therapeutic strategy for MLL-rearranged infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients carrying RAS mutations. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 14835–14846.

- Holland, M.; Castro, F.V.; Alexander, S.; Smith, D.; Liu, J.; Walker, M.; Bitton, D.; Mulryan, K.; Ashton, G.; Blaylock, M.; et al. RAC2, AEP, and ICAM1 expression are associated with CNS disease in a mouse model of pre-B childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2011, 118, 638–649.

- Nakata, Y.; Kondoh, K.; Fukushima, S.; Hashiguchi, A.; Du, W.; Hayashi, M.; Fujimoto, J.-i.; Hata, J.-i.; Yamada, T. Mutated D4-guanine diphosphate–dissociation inhibitor is found in human leukemic cells and promotes leukemic cell invasion. Exp. Hematol. 2008, 36, 37–50.

- Freret, M.; Gouel, F.; Buquet, C.; Legrand, E.; Vannier, J.-P.; Vasse, M.; Dubus, I. Rac-1 GTPase controls the capacity of human leukaemic lymphoblasts to migrate on fibronectin in response to SDF-1α (CXCL12). Leuk. Res. 2011, 35, 971–973.

- Arnaud, M.-P.; Vallée, A.; Robert, G.; Bonneau, J.; Leroy, C.; Varin-Blank, N.; Rio, A.-G.; Troadec, M.-B.; Galibert, M.-D.; Gandemer, V. CD9, a key actor in the dissemination of lymphoblastic leukemia, modulating CXCR4-mediated migration via RAC1 signaling. Blood 2015, 126, 1802–1812.

- Ueyama, T.; Geiszt, M.; Leto, T.L. Involvement of Rac1 in Activation of Multicomponent Nox1- and Nox3-Based NADPH Oxidases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 2160–2174.

- Madajewski, B.; Boatman, M.A.; Chakrabarti, G.; Boothman, D.A.; Bey, E.A. Depleting Tumor-NQO1 Potentiates Anoikis and Inhibits Growth of NSCLC. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 14–25.

- Ross, D.; Siegel, D. Functions of NQO1 in Cellular Protection and CoQ10 Metabolism and its Potential Role as a Redox Sensitive Molecular Switch. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8.

- Diao, J.; Bao, J.; Peng, J.; Mo, J.; Ye, Q.; He, J. Correlation between NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 C609T polymorphism and increased risk of esophageal cancer: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2017, 9, 13–21.

- Smith, M.T.; Wang, Y.; Skibola, C.F.; Slater, D.J.; Nigro, L.L.; Nowell, P.C.; Lange, B.J.; Felix, C.A. Low NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase activity is associated with increased risk of leukemia with MLL translocations in infants and children. Blood 2002, 100, 4590–4593.

- Freriksen, J.J.M.; Salomon, J.; Roelofs, H.M.J.; te Morsche, R.H.M.; van der Stappen, J.W.J.; Dura, P.; Witteman, B.J.M.; Lacko, M.; Peters, W.H.M. Genetic polymorphism 609C>T in NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 enhances the risk of proximal colon cancer. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 59, 381–386.

- Wiemels, J.L.; Pagnamenta, A.; Taylor, G.M.; Eden, O.B.; Alexander, F.E.; Greaves, M.F. A lack of a functional NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase allele is selectively associated with pediatric leukemias that have MLL fusions. United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 4095–4099.

- Manesia, J.K.; Xu, Z.; Broekaert, D.; Boon, R.; van Vliet, A.; Eelen, G.; Vanwelden, T.; Stegen, S.; Van Gastel, N.; Pascual-Montano, A.; et al. Highly proliferative primitive fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells are fueled by oxidative metabolic pathways. Stem. Cell Res. 2015, 15, 715–721.

- Ma, Y.; Kong, J.; Yan, G.; Ren, X.; Jin, D.; Jin, T.; Lin, L.; Lin, Z. NQO1 overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 414.

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, T.; Men, J.; Lin, Z.; Qi, P.; Piao, Y.; Yan, G. NQO1 protein expression predicts poor prognosis of non-small cell lung cancers. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 207.

- Motea, E.A.; Huang, X.; Singh, N.; Kilgore, J.A.; Williams, N.S.; Xie, X.J.; Gerber, D.E.; Beg, M.S.; Bey, E.A.; Boothman, D.A. NQO1-dependent, Tumor-selective Radiosensitization of Non-small Cell Lung Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2601–2609.

- Aggarwal, V.; Tuli, H.S.; Varol, A.; Thakral, F.; Yerer, M.B.; Sak, K.; Varol, M.; Jain, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sethi, G. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Progression: Molecular Mechanisms and Recent Advancements. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 735.

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Et. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 2977–2992.

- Fidyt, K.; Pastorczak, A.; Goral, A.; Szczygiel, K.; Fendler, W.; Muchowicz, A.; Bartlomiejczyk, M.A.; Madzio, J.; Cyran, J.; Graczyk-Jarzynka, A.; et al. Targeting the thioredoxin system as a novel strategy against B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 1180–1195.

- Inoue, H.; Takemura, H.; Kawai, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Ueda, T.; Miyashita, T. Dexamethasone-resistant human Pre-B leukemia 697 cell line evolving elevation of intracellular glutathione level: An additional resistance mechanism. Jpn. J Cancer Res. 2002, 93, 582–590.

- Tome, M.E.; Baker, A.F.; Powis, G.; Payne, C.M.; Briehl, M.M. Catalase-overexpressing thymocytes are resistant to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis and exhibit increased net tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2766–2773.

- Jaramillo, M.C.; Frye, J.B.; Crapo, J.D.; Briehl, M.M.; Tome, M.E. Increased manganese superoxide dismutase expression or treatment with manganese porphyrin potentiates dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 5450–5457.

- Kearns, P.R.; Pieters, R.; Rottier, M.M.A.; Pearson, A.D.J.; Hall, A.G. Raised blast glutathione levels are associated with an increased risk of relapse in childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2001, 97, 393–398.

- Xiao, S.; Xu, N.; Ding, Q.; Huang, S.; Zha, Y.; Zhu, H. LncRNA VPS9D1-AS1 promotes cell proliferation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia through modulating GPX1 expression by miR-491-5p and miR-214-3p evasion. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20193461.

- Kordes, U.; Krappmann, D.; Heissmeyer, V.; Ludwig, W.D.; Scheidereit, C. Transcription factor NF-kappaB is constitutively activated in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia 2000, 14, 399–402.

- Nagel, D.; Vincendeau, M.; Eitelhuber, A.C.; Krappmann, D. Mechanisms and consequences of constitutive NF-kappaB activation in B-cell lymphoid malignancies. Oncogene 2014, 33, 5655–5665.

- Smale, S.T. Hierarchies of NF-kappaB target-gene regulation. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 689–694.

- Wardyn, J.D.; Ponsford, A.H.; Sanderson, C.M. Dissecting molecular cross-talk between Nrf2 and NF-kappaB response pathways. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 621–626.

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z. Redox Control in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: From Physiology to Pathology and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cells 2021, 10, 1218.

- Oeckinghaus, A.; Ghosh, S. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 2009, 1, a000034.

- Anrather, J.; Racchumi, G.; Iadecola, C. NF-kappaB regulates phagocytic NADPH oxidase by inducing the expression of gp91phox. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 5657–5667.

- Madrid, L.V.; Mayo, M.W.; Reuther, J.Y.; Baldwin, A.S., Jr. Akt stimulates the transactivation potential of the RelA/p65 Subunit of NF-kappa B through utilization of the Ikappa B kinase and activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 18934–18940.

- Vasudevan, K.M.; Gurumurthy, S.; Rangnekar, V.M. Suppression of PTEN expression by NF-kappa B prevents apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 24, 1007–1021.

- Gu, L.; Zhu, N.; Findley, H.W.; Zhou, M. Loss of PTEN Expression Induces NF-kB Via PI3K/Akt Pathway Involving Resistance to Chemotherapy in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Lines. Blood 2004.

- Katerndahl, C.D.S.; Heltemes-Harris, L.M.; Willette, M.J.L.; Henzler, C.M.; Frietze, S.; Yang, R.; Schjerven, H.; Silverstein, K.A.T.; Ramsey, L.B.; Hubbard, G.; et al. Antagonism of B cell enhancer networks by STAT5 drives leukemia and poor patient survival. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 694–704.

- Hoelbl, A.; Schuster, C.; Kovacic, B.; Zhu, B.; Wickre, M.; Hoelzl, M.A.; Fajmann, S.; Grebien, F.; Warsch, W.; Stengl, G.; et al. Stat5 is indispensable for the maintenance of bcr/abl-positive leukaemia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2010, 2, 98–110.

- Schwaller, J.; Parganas, E.; Wang, D.; Cain, D.; Aster, J.C.; Williams, I.R.; Lee, C.K.; Gerthner, R.; Kitamura, T.; Frantsve, J.; et al. Stat5 is essential for the myelo- and lymphoproliferative disease induced by TEL/JAK2. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 693–704.

- Degryse, S.; de Bock, C.E.; Cox, L.; Demeyer, S.; Gielen, O.; Mentens, N.; Jacobs, K.; Geerdens, E.; Gianfelici, V.; Hulselmans, G.; et al. JAK3 mutants transform hematopoietic cells through JAK1 activation, causing T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a mouse model. Blood 2014, 124, 3092–3100.

- Wang, J.; Rao, Q.; Wang, M.; Wei, H.; Xing, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Tang, K.; Peng, L.; Tian, Z.; et al. Overexpression of Rac1 in leukemia patients and its role in leukemia cell migration and growth. Biochem. Biophys Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 769–774.

- Cabrera, M.; Echeverria, E.; Lenicov, F.R.; Cardama, G.; Gonzalez, N.; Davio, C.; Fernandez, N.; Menna, P.L. Pharmacological Rac1 inhibitors with selective apoptotic activity in human acute leukemic cell lines. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 98509–98523.

- Tonelli, C.; Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1727–1745.

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426.

- Akin-Bali, D.F.; Aktas, S.H.; Unal, M.A.; Kankilic, T. Identification of novel Nrf2/Keap1 pathway mutations in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 37, 58–75.

- Behan, J.W.; Yun, J.P.; Proektor, M.P.; Ehsanipour, E.A.; Arutyunyan, A.; Moses, A.S.; Avramis, V.I.; Louie, S.G.; Butturini, A.; Heisterkamp, N.; et al. Adipocytes impair leukemia treatment in mice. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 7867–7874.

- Sheng, X.; Tucci, J.; Parmentier, J.-H.; Ji, L.; Behan, J.W.; Heisterkamp, N.; Mittelman, S.D. Adipocytes cause leukemia cell resistance to daunorubicin via oxidative stress response. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 73147.

- Benjamin, C.E.; Rafal, R.A.; John, P.M.; Paraskevi, D.; Allison, B. Investigating chemoresistance to improve sensitivity of childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia to parthenolide. Haematologica 2018, 103, 1493–1501.

- Drab, M.; Stopar, D.; Kralj-Iglič, V.; Iglič, A. Inception Mechanisms of Tunneling Nanotubes. Cells 2019, 8, 626.

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Qiu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Cai, J.; Wang, B.; Wei, X.; Ke, Q.; Sui, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cell adhesion-mediated mitochondria transfer contributes to mesenchymal stem cell-induced chemoresistance on T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 11.

- Polak, R.; de Rooij, B.; Pieters, R.; den Boer, M.L. B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells use tunneling nanotubes to orchestrate their microenvironment. Blood 2015, 126, 2404–2414.

- Hawkins, E.D.; Duarte, D.; Akinduro, O.; Khorshed, R.A.; Passaro, D.; Nowicka, M.; Straszkowski, L.; Scott, M.K.; Rothery, S.; Ruivo, N.; et al. T-cell acute leukaemia exhibits dynamic interactions with bone marrow microenvironments. Nature 2016, 538, 518–522.

- Fahy, L.; Calvo, J.; Chabi, S.; Renou, L.; Le Maout, C.; Poglio, S.; Leblanc, T.; Petit, A.; Baruchel, A.; Ballerini, P.; et al. Hypoxia favors chemoresistance in T-ALL through an HIF1α-mediated mTORC1 inhibition loop. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 513–526.

- Chen, C.; Hao, X.; Lai, X.; Liu, L.; Zhu, J.; Shao, H.; Huang, D.; Gu, H.; Zhang, T.; Yu, Z.; et al. Oxidative phosphorylation enhances the leukemogenic capacity and resistance to chemotherapy of B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd6280.

- Takahashi, H.; Inoue, J.; Sakaguchi, K.; Takagi, M.; Mizutani, S.; Inazawa, J. Autophagy is required for cell survival under L-asparaginase-induced metabolic stress in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 4267–4276.

- Wu, X.; Feng, X.; Zhao, X.; Ma, F.; Liu, N.; Guo, H.; Li, C.; Du, H.; Zhang, B. Role of Beclin-1-Mediated Autophagy in the Survival of Pediatric Leukemia Cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 39, 1827–1836.

- Jing, B.; Jin, J.; Xiang, R.; Liu, M.; Yang, L.; Tong, Y.; Xiao, X.; Lei, H.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; et al. Vorinostat and quinacrine have synergistic effects in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia through reactive oxygen species increase and mitophagy inhibition. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 589.