Lymphatic vessels drain lymph from interstitial spaces and serosal cavities to eventually empty into the blood venous stream. This task is more difficult when the liquid to be drained has a very subatmospheric pressure, as it occurs in the pleural cavity. This peculiar space must maintain a very low fluid volume at negative hydraulic pressure to guarantee a proper mechanical coupling between the chest wall and lungs. Moreover, lubrication of the constant sliding pleurae to avoid any damage to those very thin structures, constant liquid renovation preventing excessive drying, or accumulation must be fulfilled at the same time.

- lymphatic vessel

- pleural cavity

- diaphragm

- chest wall

- lung

1. Lymph Draining and Propulsion

The lymphatic system drains liquid, macromolecules and cells from the surrounding interstitial space and serosal cavities, to guarantee the proper tissue fluid balance[1]. Lymph formation occurs into lymphatic capillaries, which are blind-ended vessels originating in peripheral tissue, devoid of lymphatic muscle cells (LMCs). Those vessels are lined by a single layer of overlapping endothelial cells (LECs) forming primary unidirectional valves, allowing lymph entry and preventing the backflow into surrounding tissue[2][3][4][5]. The forces required for lymph formation and propulsion are modelled according to the modified Starling’s Law Equation (1)[6]. The hydraulic pressure gradient is the main determinant of lymph flow (Jlymph) across the capillaries’ wall and through the lymphatic network.

(1)

(1)where Lp is the endothelial permeability to water coefficient, S the surface area of fluid exchange and ΔPTM the transmural hydraulic pressure gradient between the lymphatic capillary lumen (PL) and the interstitium (Pin). Jlymph is directly dependent upon the plasma filtered from blood capillaries into the interstitium and the mechanical compliance of the receiving space: the more fluid enters the interstitium the greater fluid volume is drained by lymphatics, whose intraluminal pressure (PL) is typically subatmospheric.

Due to anchoring filaments[7], lymphatic capillaries are tightly attached to the extracellular matrix[6][8] and tissue displacement causes extrinsic forces to cyclically expand and compress lymphatic vessels, affecting ΔPTM, thus lymph formation. Lymph is then propelled through larger collecting lymphatics, surrounded by LMCs displaying unique features[9]. Intraluminal competent valves separate adjacent lymphangions (the functional pump units of the lymphatic system) and prevent massive lymph backflow[4][8][10]. Lymph progression is then due to a net intraluminal hydraulic pressure gradient acting across the trans-valve region (ΔPtv). In vivo micropuncture studies measured a ΔPtv of ~1–1.5 cmH2O[11] which forces the valve to open. More recently, PL measurements in mesenteric lymphatics having different pressure regimens showed multiple gating patterns, depending on the baseline PL and on the vessel wall’s distension[12]. Indeed, valve closure may occur with an adverse ΔPtv as low as 0.1 cmH2O for baseline PL below 2 cmH2O, but a ΔPtv higher than 2 cmH2O is required to force valve closure with a baseline PL of 10 cmH2O or above. Moreover, pressure ranges for valve opening and closure are not symmetrical, causing valves to be biased in an open position having multiple physiological implications and can also lead to a limited lymph backflow[13][14]. Nevertheless, lymph is propelled against an overall hydraulic pressure gradient to the blood venous system[11][15]. Lymphatic spontaneous phasic contractions (intrinsic forces)[16] arising in collecting vessels walls combined to extrinsic mechanisms, drive lymph propulsion centripetally, critically affecting intraluminal pressure gradients. Spontaneous contractions of the lymphatic muscle[9][17][18][19][20] typically spread from a subset of LMCs in the vessel wall and propagates along the lymphatic network through gap junctions between LMCs and/or LECs[15].

2. The Pleural Space

The pleural space in the thoracic cavity is a very peculiar serosal compartment whose integrity is vital for a physiological breathing. The mechanical properties of lungs and chest wall are set so that each of them tends to reach its mechanical resting volume: lungs tend to the very low minimal air volume (lower than zero vital capacity) whereas the chest wall tends to a value ~80% of the vital capacity[21]. In so doing, they both tend to increase the pleural cavity volume, inducing Pliq (pleural hydraulic pressure, analogous to Pin for the pleural cavity) to reach subatmospheric pressure values during normal, spontaneous breathing. In humans, at end-expiration at the height of the right atrium Pliq is ~–5 cmH2O, becoming more negative during inspiration. Pleural Pliq only becomes positive during forced expiration. The negative Pliq ensures the proper mechanical coupling between the chest wall and the lungs, but it implies that the removal of liquid filtered from capillaries and surrounding tissues is more difficult to achieve.

3. Lymphatic Vessels of the Diaphragm

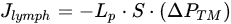

Lymphatic vessels of the diaphragm allow fluid homeostasis of the pleural (and peritoneal) cavities, due to their subatmospheric PL. On the pleural side, lymphatic vessels are organized in linear vessels, with a parallel or transverse arrangement with respect to the skeletal muscle fibers orientation, or in complex merging structures (lymphatic loops)[22][23]. Unlike pleural lymphatics, on the peritoneal side, lymphatics are radially arranged from the abdominal wall to the central tendon[24]. They primarily remove peritoneal fluid, but also pathogens and/or immune cells related to inflammatory state affecting the viscera, such as the gastrointestinal tract or the urogenitary system. Lymph drained from serosal cavities enters the diaphragmatic network through mesothelial stomata[25], reaching flat submesothelial lymphatic lacunae (Figure 1, asterisks), considered as larger lymphatic capillaries. Lacunae are unevenly distributed and located beneath the mesothelium and above the skeletal muscle layer[26]. They empty into transverse lymphatic vessels draining into collecting lymphatics deeper in the interstitium[27]. Lymph is then routed towards the mediastinal lymph nodes, merging to the blood stream via the thoracic duct.

Intrinsic and/or extrinsic forces deeply affect diaphragmatic lymphatics’ draining and propulsive capability. Regarding extrinsic forces, the cyclical contraction of the diaphragm during the respiratory cycle plays a pivotal role in determining lymphatic function. Cyclical mechanical stresses transmitted to lymphatics primarily affect ΔPTM and the intraluminal pressure gradient (ΔPL = PL,1 − PL,2) between two lymphatic segments. The external stress transmission efficiency depends upon both the mechanical properties of the lymphatics’ wall and the surrounding tissue, being more effective in stiffer rather than more distensible regions[28]. Moreover, depending on vessels’ orientation with respect to the skeletal muscle fibers, extrinsic forces can either shrink or enlarge the vessel lumen, affecting lymphangions’ volume and hydraulic PL and Pin profiles.

Figure 1. In vivo fluorescent stained lymphatic network on the pleural side of rat diaphragm. Lymph enters lymphatic lacunae (asterisks) and is propelled through vessels longitudinally (L) and/or perpendicularly (P) arranged with respect to the skeletal muscle fibers orientation. Lymphatic collectors located at the muscle periphery, next to the costal margin, are typically organized in complex loop structures (loop) and display intrinsic contractility (scalebar 1 mm).

Diaphragmatic skeletal muscle contractions reduce vessels’ diameter by ~39% in superficial, perpendicularly oriented lymphatics (Figure 1, P), decreasing PL by ~12 cmH2O and enhancing the pressure gradient driving force (ΔPTM) favoring lymph formation. Conversely in deeper collectors the diaphragm contraction increases PL by ~11 cmH2O, favoring lymph propulsion. In longitudinally oriented lymphatics (Figure 1, L) diaphragmatic muscle contraction shortens the vessel by ~30% and the diameter enlarges by ~23%. PL decreases in both superficial submesothelial and deeper vessels by ~22.5 cmH2O and ~10.5 cmH2O respectively, thereby supporting further lymph propulsion[29]. The different regional effect may be explained considering that deeper lymphatics are less compliant being entirely surrounded by stiffer skeletal or tendinous fibers[28]. Moreover, another source of extrinsic forces is the rhythmic tissue displacement due to heart activity, as cardiogenic movements induced by arterial pressure pulses propagate through neighbor regions, affecting the diaphragmatic lymphatic bed and the adjacent interstitium. Cardiogenic activity can simultaneously sustain lymph formation and propulsion along the lymphatic network of the diaphragm. Indeed, data obtained in rats shows that in ~60% of cases ΔPTM sustains lymph formation during either systolic or diastolic phases, whereas in ~40% of cases ΔPTMbecomes transiently positive, possibly driving fluid backflow into the interstitial space but also sustaining oscillatory lymph propulsion along lymphatic collectors[30].

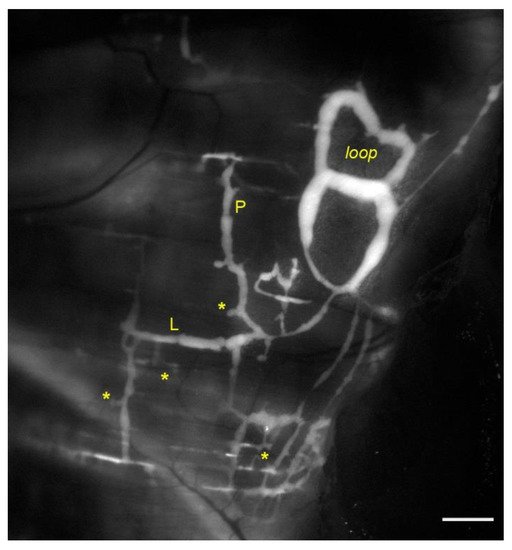

Diaphragmatic collecting lymphatics located at the far peripheral muscular region adjacent to the costal margin are typically organized in complex loops (Figure 1, loop). These vessels are endowed with a properly organized dense mesh of lymphatic muscle (Figure 2, panel A) spontaneously contracting[23][31] aiding lymph propulsion. In this body district, intrinsic spontaneous contractions rely on a “Funny”-like current (If) due to HCN (Hypolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated) channels[32][33], as it occurs in the heart pacemaker. This intrinsic contractility can be reduced by Cesium[33][34] or even abolished by two well-known HCN channel blockers, Ivabradine[35] and/or ZD7288[34]. In analogy to the cardiac cycle, the intrinsic contractile mechanism can be divided into an active systolic contraction followed by a diastolic relaxation, and it can be quantified in terms of contraction frequency (CF) and contraction amplitude (Δd, the difference between the end-diastolic and the end-systolic diameters)[36].

In rat diaphragm extrinsic forces are the most efficient and guarantee a proper one-way propulsion by forcing intraluminal valves into an open/closed cycle[29], preventing backflow. In fact, the extrinsically induced lymph progression along the vessel network is ~30 times longer, and lymph flow is 10-fold higher, than the ones induced by a single intrinsic contraction. Nevertheless, lymph flow remains laminar also for extrinsic pumping mechanism[14].

Then, why is the intrinsic mechanism also needed in diaphragmatic lymphatics? It seems to be restricted to the muscular peripheral vessels[23], located in an area where the respiratory-related extrinsic forces are less effective, probably due to the anisotropic stress distribution in the diaphragmatic dome[37]. Indeed, it is worth noting that lymphatics vessels in the medial muscular region also possess LMCs, although they do not spontaneously contract, being the lymphatic muscle not properly arranged to aid lymph propulsion[23]. Moreover, the abundance of LMCs in the vessel wall, beyond a certain level, may not be determinant for the contraction amplitude (Δd), as it reaches a finite saturation limit for increasing LMCs density, not corresponding to complete occlusion of the lymphatic lumen[38] (Figure 2, panel B).

Figure 2. Rat pleural diaphragmatic lymphatics (A) Confocal image of a lymphatic vessel in vivo stained with FITC-dextrans (green signal) and whole mount stained for LMCs (red signal), highlighting the organization of the lymphatic muscle mesh surrounding the vessel (scalebar 100 µm). (B) Plot of intrinsic Δd correlating to the lymphatic muscle density in the vessels’ wall. (C) Plot of the dependence of intrinsic CF from temperature in the range 34–40 °C (green trace), which is completely abolished by the selective TRPV4 channels antagonist HC067047 (black dashed line). (D) Plot of osmolarity-induced modulation of intrinsic CF: the hyperosmolar environment (red trace) induces a sigmoidal decease in CF, whereas hyposmolarity induces an acute early CF increase (blue dashed line) followed by a later decrease (blue solid line).

Spontaneous LMCs contractions seem to allow lymph recirculation into peripheral lymphatic loops, thus preventing fluid accumulation which may result in the development of oedema. They can be modulated by tissue temperature, as lymphatics rapidly adjust CF to temperature changes in the physiological range 35–39 °C (Figure 2, panel C, green trace), as it can occur during circadian oscillations of temperature, in case of fever or during physical exercise. In rat diaphragmatic lymphatics raising temperatures exert an increase in CF (positive chronotropic effect), while simultaneously reduce Δd (negative inotropic effect). However, as the chronotropic effect prevails, raising the temperature rapidly increases lymph flow[39][40]. Diaphragmatic lymphatics lay in the thermal core at 37 °C, and sense changes in temperature via the TRPV4 (Transient Receptor Potential channel Vanilloid 4) thermal sensor[41], blocked by its specific antagonist HC067047[42], giving rise to a temperature-insensitive behavior (Figure 2, panel C, black dashed line). Conversely, specifically activating TRPV4 receptors through GSK1016790A[43] results in a behavior mirroring the response to increasing temperature. Changes in the surrounding osmolarity give rise to a more complex pattern[44]. When rat diaphragmatic lymphatics are exposed to a hyperosmotic environment up to 324 mOsm (Figure 2, panel D) CF decreases in an osmotic-dependent manner, which seems to represent a tissue fluid-saving mechanism. On the other hand, the exposure to a hyposmotic interstitial fluid at 290 mOsm exerts a biphasic behavior, displaying an early transient CF increase (Figure 2, panel D, blue dashed line), which probably responds to the necessity of removing a greater fluid volume filtered. However, later CF decreases attaining an osmolarity-independent steady plateau (Figure 2, panel D, blue solid line). As in both hyper- and hypo-osmotic environments no inotropic effects can be found, changes in lymph flow are qualitatively similar to the ones in CF[44].

The coexistence of both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms driving lymph dynamics makes the diaphragm a very intriguing model to study the mechanisms of lymphatic functionality. Indeed, in most tissues lymph formation and propulsion mainly relies on extrinsic forces as it occurs in highly moving tissues such as other skeletal muscles, lungs and the heart[8][45][46][47]. Conversely, in lymphatics immersed in soft tissues, almost completely devoid of tissue displacement, the lymphatic draining capability totally depends upon intrinsic contractility.

4. Pleural Intercostal Lymphatics

The pleural cavity is covered by parietal and visceral mesothelial pleura, which respectively overlay the internal intercostal respiratory muscles and the lungs. Parietal pleural lymphatics of the intercostal spaces open directly in the pleural cavity, thus forming a direct funnel to the draining lymphatic system[48]. Those vessels might share some of the features of the diaphragmatic vessels, especially those related with the extrinsic forces sustaining lymph formation and propulsion. Larger lymphatic vessels lay parallel and in proximity with the ribs and/or sternum offering a suitable site for hydraulic pressures measurement[49]. During spontaneous breathing the simultaneous recording of PL and Pin in rats’ intercostal vessels shows a variability of both, related to the phase of the respiratory cycle[50]. PL and Pin reach their lowest values at the end of the inspiratory phase (about −28.5 and −16.5 cmH2O respectively), with PL remaining subatmospheric and below Pin most of the times This, in turn, results in a ΔPTMfavoring lymph formation in most vessels during the whole respiratory cycle, with an apparent prevailing role of tissue displacement over the respiratory rate to drive lymph draining. However, in a small fraction of the intercostal vessels ΔPTM favors lymph propulsion for the entire respiratory cycle, whereas for some vessels their behavior changes from formation to propulsion in the transition between inspiration and expiration. Therefore, the spontaneous respiratory activity maximizes lymph formation while preserving lymph progression along the lymphatic network, being both mechanisms essential for pleural liquid volume homeostasis

The situation completely changes during controlled mechanical ventilation, even by setting respiratory parameters equal to spontaneous breathing. Pin and PL values increase with increasing lung volume, reaching their maximal value at end-inspiration (about 38 cmH2O for both) and, most notably, PL becomes positive. The difference between PL and tissue Pin diminishes throughout the whole respiratory cycle, almost nullifying ΔPTM, with a severe impact on both lymph formation and propulsion. The analysis in the frequency domain of the various components of Pin, PL and ΔPTM reveals that in spontaneous breathing all of them are dominated by the respiratory rate. Conversely, during mechanical ventilation the relative power of the respiratory-driven frequency component of ΔPTM is greatly reduced and becomes almost as low as the one of the cardiogenic oscillations in pressure[50].

Overall, in the transition from spontaneous breathing to mechanical ventilation, both draining and propulsive functions of costal lymphatics are severely depressed, leaving only the lesser functional cardiogenic activity to sustain a very limited lymph fluid removal from the pleural space. Thus, lymph formation is severely attenuated during mechanical ventilation, being Pliq subatmospheric, increasing the hydration state both of pleural space and lung tissues. This phenomenon alone might therefore partially explain mild- to moderate oedematous conditions and difficulties in breathing often evident in patients which undergo prolonged periods of mechanical ventilation at positive alveolar air pressures.

5. Lymphatic Vessels of Lungs

The lymphatic system draining the lungs can be divided into lymphatics serving the upper airways, the tracheobronchial tree, and the lung parenchyma. Pulmonary lymphatics are organized into pleural vessels, located in close contact with the lung parenchyma, and interlobular or intralobular lymphatics of the loose connective tissue. The latter include bronchovascular, perivascular, peribronchiolar and interalveolar lymphatic vessels[51][52][53][54]. Lymphatic clearance routes change with lung height, as in the upper regions lymph formation prevails in bronchovascular lymphatics, whereas in the lower ones it is predominant in subpleural/septal zones[55]. Overall, lymph clearance is greater in lymphatics located in lower than in upper regions of the lung[56]. In humans, the lymphatic system begins to develop between the 6th and 7th week of pregnancy, whereas in mice it appears around embryonic day 10 (E10.0). During embryogenesis the expression of VEGFC (Vascular endothelial growth factor C)[57] and VEGFR3 (Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3)[58] is involved in pulmonary lymphatics formation, critical for lung development. Indeed, mice lacking lymphatic vessels die at birth due to respiratory failure, despite a normally developed lung parenchyma and a proper amount of surfactant. However, the wet/dry ratio indicates the development of pulmonary oedema, significantly reducing the compliance of lung parenchyma and thickening the interstitium. As a result, mice are unable to inflate lungs at birth[59]. Moreover, mice lacking the α9 integrin appear normal at birth, but they develop late-onset respiratory distress and die between 6–12 days after birth due to pleural fluid effusion and liquid accumulation[60].

The difficulty to stain the lymphatic vessels but not the surrounding interstitial and/or alveolar spaces is still a technical limit that jeopardizes every attempt to in situ measure PL in the intact pleural cavity. Nevertheless, measures of pulmonary Pin have been performed with the intact pleural space, showing a very negative environment, with pressures ranging from about −13.5 cmH2O at end-expiration to ~−20/–27 cmH2O at end inspiration, during spontaneous breathing[61][62]. These extreme negative hydraulic pressures are a prerequisite to maintain a very thin and dry alveolar interstitial space, optimizing the gas exchange. Moreover, the pulmonary interstitial space possesses a so-called “safety factor”[63], due to a very stiff extracellular matrix, forcing Pin to rapidly increase above zero when liquid accumulates in the interalveolar spaces. In addition, a greater interstitial fluid volume induces anchoring filaments to stretch, thus exerting a radial tension on the lymphatic capillaries’ wall which opens primary valves increasing lymph formation[6]. Pulmonary lymphatic vessels contribute to the proper lung extracellular matrix organization by maintaining hyaluronan (HA) homeostasis removing the excess of HA fragments through the LYVE1 receptor (Lymphatic Vessel Endothelial Hyaluronan Receptor 1)[64]. Water binds to HA increasing Pin favoring fluid clearance by lymphatic vessels[65]. Lung oedema may develop due to an increase in fluid filtration across blood capillaries exceeding the lymphatic transport capacity. The wet/dry ratio increases up to values that cannot be compensated by lymphatic reabsorption, which seem to be correlated to large matrix fragmentation which damages the lung parenchyma and air-blood barrier. Indeed, the glycosaminoglycans degradation to low molecular weight fragments, especially HA and chondroitin-sulphate, impact the lung interstitial scaffold dramatically decreasing the effectiveness of the “safety factor”[65][66]. Similar effects are also related to the stress/strain of different ventilatory strategies. In rat, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) combined with mechanical ventilation at high tidal volume (VT) display damaging effects on the lung parenchyma, due to tissue overdistension. Furthermore, injurious effects of mechanical ventilation are exacerbated by oedemagenic conditions. On the contrary, combining low VT mechanical ventilation to PEEP results to be protective toward lung parenchyma fragmentation[66]. Moreover, PEEP would increase Pin, thus favoring lymph formation and oedema reduction.

The few PL measurements from lung lymphatic vessels cannot allow but to speculate on their physiological properties and role in fluid drainage from lung interstitial space. From what has been observed both in the diaphragmatic and parietal lymphatics, it could be argued that during inspiration the stretch experienced by lung parenchyma could be transmitted to lymphatic vessels, being the extrinsic mechanism pivotal for pulmonary lymphatic function as lung collecting vessels lack LMCs[67]. This, in turn, might cause a more negative PL, which is the prerequisite to drain lymph from a very subatmospheric lung Pin. Recently developed transgenic animal models could potentially be useful tools to close the gap in this field of lymphatic physiology[68][69][70].

References

- Helge Wiig; Melody A. Swartz; Interstitial Fluid and Lymph Formation and Transport: Physiological Regulation and Roles in Inflammation and Cancer. Physiological Reviews 2012, 92, 1005-1060, 10.1152/physrev.00037.2011.

- Lee V. Leak; STUDIES ON THE PERMEABILITY OF LYMPHATIC CAPILLARIES. Journal of Cell Biology 1971, 50, 300-323, 10.1083/jcb.50.2.300.

- Jürgen Trzewik; S. K. Mallipattu; Gerhard M. Artmann; F. A. Delano; Geert W. Schmid-Schonbein; Evidence for a second valve system in lymphatics: endothelial microvalves. The FASEB Journal 2001, 15, 1711-1717, 10.1096/fj.01-0067com.

- Eleni Bazigou; John T. Wilson; James Moore; Primary and secondary lymphatic valve development: Molecular, functional and mechanical insights. Microvascular Research 2014, 96, 38-45, 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.07.008.

- Peter Baluk; Jonas Fuxe; Hiroya Hashizume; Talia Romano; Erin Lashnits; Stefan Butz; Dietmar Vestweber; Monica Corada; Cinzia Molendini; Elisabetta Dejana; et al.Donald M. McDonald Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2007, 204, 2349-2362, 10.1084/jem.20062596.

- K. Aukland; Rolf K. Reed; Interstitial-lymphatic mechanisms in the control of extracellular fluid volume. Physiological Reviews 1993, 73, 1-78, 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.1.

- L V Leak; J F Burke; Ultrastructural studies on the lymphatic anchoring filaments.. Journal of Cell Biology 1968, 36, 129-49.

- G. W. Schmid-Schonbein; Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiological Reviews 1990, 70, 987-1028, 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987.

- Mariappan Muthuchamy; Anatoliy Gashev; Niven Boswell; Nancy Dawson; David Zawieja; Molecular and functional analyses of the contractile apparatus in lymphatic muscle. The FASEB Journal 2003, 17, 920-22, 10.1096/fj.02-0626fje.

- Eleni Bazigou; Taija Makinen; Flow control in our vessels: vascular valves make sure there is no way back. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2012, 70, 1055-1066, 10.1007/s00018-012-1110-6.

- B W Zweifach; J W Prather; Micromanipulation of pressure in terminal lymphatics in the mesentery. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 1975, 228, 1326-1335, 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.228.5.1326.

- Michael J. Davis; Elaheh Rahbar; Anatoliy A. Gashev; David Zawieja; James Moore; Determinants of valve gating in collecting lymphatic vessels from rat mesentery. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2011, 301, H48-H60, 10.1152/ajpheart.00133.2011.

- J. Brandon Dixon; Steven T. Greiner; Anatoliy A. Gashev; Gerard L. Cote; James E. Moore Jr.; David C. Zawieja; Lymph Flow, Shear Stress, and Lymphocyte Velocity in Rat Mesenteric Prenodal Lymphatics. Microcirculation 2006, 13, 597-610, 10.1080/10739680600893909.

- Andrea Moriondo; Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Lymph flow pattern in pleural diaphragmatic lymphatics during intrinsic and extrinsic isotonic contraction. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2016, 310, H60-H70, 10.1152/ajpheart.00640.2015.

- David Zawieja; K. L. Davis; R. Schuster; W. M. Hinds; H. J. Granger; Distribution, propagation, and coordination of contractile activity in lymphatics. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 1993, 264, H1283-H1291, 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.4.h1283.

- Joshua P. Scallan; Scott D. Zawieja; Jorge Castorena-Gonzalez; Michael J. Davis; Lymphatic pumping: mechanics, mechanisms and malfunction. The Journal of Physiology 2016, 594, 5749-5768, 10.1113/jp272088.

- N G McHale; M K Meharg; Co-ordination of pumping in isolated bovine lymphatic vessels.. The Journal of Physiology 1992, 450, 503-512, 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019139.

- Pierre-Yves von der Weid; David Zawieja; Lymphatic smooth muscle: the motor unit of lymph drainage. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2004, 36, 1147-1153, 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.12.008.

- Eric A. Bridenbaugh; Anatoliy A. Gashev; David C. Zawieja; Lymphatic Muscle: A Review of Contractile Function. Lymphatic Research and Biology 2003, 1, 147-158, 10.1089/153968503321642633.

- Pierre-Yves von der Weid; Lymphatic Vessel Pumping. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 2019, 1124, 357-377, 10.1007/978-981-13-5895-1_15.

- West J.B., Luks A.M.. Respiratory Physiology 11th ed.; ., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. ..

- Andrea Moriondo; Francesca Bianchin; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Kinetics of fluid flux in the rat diaphragmatic submesothelial lymphatic lacunae. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2008, 295, H1182-H1190, 10.1152/ajpheart.00369.2008.

- Andrea Moriondo; Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Spontaneous activity in peripheral diaphragmatic lymphatic loops. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2013, 305, H987-H995, 10.1152/ajpheart.00418.2013.

- Harumichi Shinohara; Lymphatic system of the mouse diaphragm: Morphology and function of the lymphatic sieve. The Anatomical Record 1997, 249, 6-15, 10.1002/(sici)1097-0185(199709)249:1<6::aid-ar2>3.0.co;2-p.

- D. Negrini; S. Mukenge; M. Del Fabbro; C. Gonano; G. Miserocchi; Distribution of diaphragmatic lymphatic stomata. Journal of Applied Physiology 1991, 70, 1544-1549, 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1544.

- D. Negrini; M. Del Fabbro; C. Gonano; S. Mukenge; G. Miserocchi; Distribution of diaphragmatic lymphatic lacunae. Journal of Applied Physiology 1992, 72, 1166-1172, 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.3.1166.

- Annalisa Grimaldi; Andrea Moriondo; Laura Sciacca; Maria Luisa Guidali; Gianluca Tettamanti; Daniela Negrini; Functional arrangement of rat diaphragmatic initial lymphatic network. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2006, 291, H876-H885, 10.1152/ajpheart.01276.2005.

- Andrea Moriondo; Federica Boschetti; Francesca Bianchin; Simone Lattanzio; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Tissue contribution to the mechanical features of diaphragmatic initial lymphatics. The Journal of Physiology 2010, 588, 3957-3969, 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.196204.

- Andrea Moriondo; Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Diaphragmatic lymphatic vessel behavior during local skeletal muscle contraction. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2015, 308, H193-H205, 10.1152/ajpheart.00701.2014.

- Daniela Negrini; Andrea Moriondo; Sylvain Mukenge; Transmural Pressure During Cardiogenic Oscillations in Rodent Diaphragmatic Lymphatic Vessels. Lymphatic Research and Biology 2004, 2, 69-81, 10.1089/lrb.2004.2.69.

- Osamu Ohtani; Yuko Ohtani; Organization and developmental aspects of lymphatic vessels. Archives of Histology and Cytology 2008, 71, 1-22, 10.1679/aohc.71.1.

- Daniela Negrini; Cristiana Marcozzi; Eleonora Solari; Elena Bossi; Raffaella Cinquetti; Marcella Reguzzoni; Andrea Moriondo; Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in peripheral diaphragmatic lymphatics. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2016, 311, H892-H903, 10.1152/ajpheart.00193.2016.

- K. D. McCloskey; H. M. Toland; Mark Hollywood; Keith Thornbury; N. G. McHale; Hyperpolarisation‐activated inward current in isolated sheep mesenteric lymphatic smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology 1999, 521, 201-211, 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00201.x.

- Robert E. BoSmith; Ian Briggs; Nicholas C. Sturgess; Inhibitory actions of ZENECA ZD7288 on whole-cell hyperpolarization activated inward current (If) in guinea-pig dissociated sinoatrial node cells. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 1993, 110, 343-349, 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13815.x.

- A. Bucchi; A. Tognati; R. Milanesi; M. Baruscotti; D. DiFrancesco; Properties of ivabradine-induced block of HCN1 and HCN4 pacemaker channels. The Journal of Physiology 2006, 572, 335-346, 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100776.

- David C. Zawieja; Contractile Physiology of Lymphatics. Lymphatic Research and Biology 2009, 7, 87-96, 10.1089/lrb.2009.0007.

- Aladin M. Boriek; Joseph R. Rodarte; Michael B. Reid; Shape and tension distribution of the passive rat diaphragm.. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2001, 280, R33-R41, 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.r33.

- Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Barbara Bartolini; Manuela Viola; Daniela Negrini; Andrea Moriondo; Acute Exposure of Collecting Lymphatic Vessels to Low-Density Lipoproteins Increases Both Contraction Frequency and Lymph Flow: AnIn VivoMechanical Insight. Lymphatic Research and Biology 2020, 18, 146-155, 10.1089/lrb.2019.0040.

- Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Andrea Moriondo; Lymphatic Vessels and Their Surroundings: How Local Physical Factors Affect Lymph Flow. Biology 2020, 9, 463, 10.3390/biology9120463.

- Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Andrea Moriondo; Temperature-dependent modulation of regional lymphatic contraction frequency and flow. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2017, 313, H879-H889, 10.1152/ajpheart.00267.2017.

- Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Michela Bistoletti; Andreina Baj; Cristina Giaroni; Daniela Negrini; Andrea Moriondo; TRPV4 channels’ dominant role in the temperature modulation of intrinsic contractility and lymph flow of rat diaphragmatic lymphatics. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2020, 319, H507-H518, 10.1152/ajpheart.00175.2020.

- Wouter Everaerts; Xiaoguang Zhen; Debapriya Ghosh; Joris Vriens; Thomas Gevaert; James P. Gilbert; Neil J. Hayward; Colleen R. McNamara; Fenqin Xue; Magdalene M. Moran; et al.Timothy StrassmaierEda UykalGrzegorz OwsianikRudi VennekensDirk De RidderBernd NiliusChristopher M. FangerThomas Voets Inhibition of the cation channel TRPV4 improves bladder function in mice and rats with cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 19084-19089, 10.1073/pnas.1005333107.

- Kevin S. Thorneloe; Anthony C. Sulpizio; Zuojun Lin; David J. Figueroa; Angela K. Clouse; Gerald P. McCafferty; Tim P. Chendrimada; Erin S. R. Lashinger; Earl Gordon; Louise Evans; et al.Blake A. MisajetDouglas J. DeMariniJosephine H. NationLinda CasillasRobert W. MarquisBartholomew J. VottaSteven A. SheardownXiaoping XuDavid P. BrooksNicholas J. LapingTimothy D. Westfall N-((1S)-1-{[4-((2S)-2-{[(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)sulfonyl]amino}-3-hydroxypropanoyl)-1-piperazinyl]carbonyl}-3-methylbutyl)-1-benzothiophene-2-carboxamide (GSK1016790A), a Novel and Potent Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 Channel Agonist Induces Urinary Bladder Contraction and Hyperactivity: Part I. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2008, 326, 432-442, 10.1124/jpet.108.139295.

- Eleonora Solari; Cristiana Marcozzi; Daniela Negrini; Andrea Moriondo; Fluid Osmolarity Acutely and Differentially Modulates Lymphatic Vessels Intrinsic Contractions and Lymph Flow. Frontiers in Physiology 2018, 9, 871, 10.3389/fphys.2018.00871.

- M. C. Mazzoni; T. C. Skalak; G. W. Schmid-Schonbein; Effects of skeletal muscle fiber deformation on lymphatic volumes. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 1990, 259, H1860-H1868, 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.6.h1860.

- Geert W. Schmid-Schönbein; Mechanisms causing initial lymphatics to expand and compress to promote lymph flow.. Archives of Histology and Cytology 1990, 53, 107-114, 10.1679/aohc.53.suppl_107.

- J G McGeown; N G McHale; Keith Thornbury; The role of external compression and movement in lymph propulsion in the sheep hind limb.. The Journal of Physiology 1987, 387, 83-93, 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016564.

- Andrew T. Mariassy; Eric B. Wheeldon; The Pleura: A Combined Light Microscopic, Scanning, and Transmission Electron Microscopic Study in the Sheep. I. Normal Pleura. Experimental Lung Research 1983, 4, 293-314, 10.3109/01902148309055016.

- Daniela Negrini; Massimo Fabbro; Subatmospheric pressure in the rabbit pleural lymphatic network. The Journal of Physiology 1999, 520, 761-769, 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00761.x.

- Andrea Moriondo; Sylvain Mukenge; Daniela Negrini; Transmural pressure in rat initial subpleural lymphatics during spontaneous or mechanical ventilation. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2005, 289, H263-H269, 10.1152/ajpheart.00060.2005.

- Trapnell D.H.; The anatomy of the lymphatics of the lungs and chest wall.. Thorax. 1970, 25, 255-256.

- L V Leak; M P Jamuar; Ultrastructure of pulmonary lymphatic vessels.. American Review of Respiratory Disease 1983, 128, S59-65, 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.2P2.S59.

- Francesca Sozio; Antonella Rossi; Elisabetta Weber; David J. Abraham; Andrew G. Nicholson; Athol U. Wells; Elisabetta A. Renzoni; Piersante Sestini; Morphometric analysis of intralobular, interlobular and pleural lymphatics in normal human lung. Journal of Anatomy 2012, 220, 396-404, 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01473.x.

- E. Weber; F. Sozio; A. Borghini; P. Sestini; E. Renzoni; Pulmonary lymphatic vessel morphology: a review. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger 2018, 218, 110-117, 10.1016/j.aanat.2018.02.011.

- Ryoko Egashira; Tomonori Tanaka; Takeshi Imaizumi; Kazutaka Senda; Yoshinori Doki; Sho Kudo; Junya Fukuoka; Differential distribution of lymphatic clearance between upper and lower regions of the lung. Respirology 2013, 18, 348-353, 10.1111/resp.12006.

- Dean E. Schraufnagel; Lung lymphatic anatomy and correlates. Pathophysiology 2010, 17, 337-343, 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.10.008.

- V. Joukov; K. Pajusola; A. Kaipainen; Dmitri Chilov; I. Lahtinen; E. Kukk; O. Saksela; N. Kalkkinen; Kari Alitalo; A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases.. The EMBO Journal 1996, 15, 290-298, 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00359.x.

- Taija Makinen; Tanja Veikkola; Satu Mustjoki; Terhi Karpanen; Bruno Catimel; Edouard C. Nice; Lyn Wise; Andrew Mercer; Heinrich Kowalski; Dontscho Kerjaschki; et al.Steven StackerMarc AchenKari Alitalo Isolated lymphatic endothelial cells transduce growth, survival and migratory signals via the VEGF-C/D receptor VEGFR-3. The EMBO Journal 2001, 20, 4762-4773, 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4762.

- Zoltán Jakus; Jason Gleghorn; David R. Enis; Aslihan Sen; Stephanie Chia; Xi Liu; David R. Rawnsley; Yiqing Yang; Paul R. Hess; Zhiying Zou; et al.Jisheng YangSusan GuttentagCeleste M. NelsonMark L. Kahn Lymphatic function is required prenatally for lung inflation at birth. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2014, 211, 815-826, 10.1084/jem.20132308.

- X. Z. Huang; J. F. Wu; R. Ferrando; J. H. Lee; Y. L. Wang; R. V. Farese; D. Sheppard; Fatal Bilateral Chylothorax in Mice Lacking the Integrin α9β1. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2000, 20, 5208-5215, 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5208-5215.2000.

- G. Miserocchi; Daniela Negrini; C. Gonano; Direct measurement of interstitial pulmonary pressure in in situ lung with intact pleural space. Journal of Applied Physiology 1990, 69, 2168-2174, 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.6.2168.

- G. Miserocchi; D. Negrini; C. Gonano; Parenchymal stress affects interstitial and pleural pressures in in situ lung. Journal of Applied Physiology 1991, 71, 1967-1972, 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.5.1967.

- Aubrey E. Taylor; James C. Parker; Peter R. Kvietys; Michael A. Perry; THE PULMONARY INTERSTITIUM IN CAPILLARY EXCHANGE. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1982, 384, 146-165, 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb21369.x.

- Suneale Banerji; Jian Ni; Shu-Xia Wang; Steven Clasper; Jeffrey Su; Raija Tammi; Margaret Jones; David G. Jackson; LYVE-1, a New Homologue of the CD44 Glycoprotein, Is a Lymph-specific Receptor for Hyaluronan. Journal of Cell Biology 1999, 144, 789-801, 10.1083/jcb.144.4.789.

- Egidio Beretta; Francesco Romanò; Giulio Sancini; James B. Grotberg; Gary F. Nieman; Giuseppe Miserocchi; Pulmonary Interstitial Matrix and Lung Fluid Balance From Normal to the Acutely Injured Lung. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 781874, 10.3389/fphys.2021.781874.

- Andrea Moriondo; Cristiana Marcozzi; Francesca Bianchin; Marcella Reguzzoni; Paolo Severgnini; Marina Protasoni; Mario Raspanti; Alberto Passi; Paolo Pelosi; Daniela Negrini; et al. Impact of mechanical ventilation and fluid load on pulmonary glycosaminoglycans. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 2012, 181, 308-320, 10.1016/j.resp.2012.03.013.

- Hasina Outtz Reed; Liqing Wang; Jarrod Sonett; Mei Chen; Jisheng Yang; Larry Li; Petra Aradi; Zoltán Jakus; Jeanine M. D'armiento; Wayne W. Hancock; et al.Mark L. Kahn Lymphatic impairment leads to pulmonary tertiary lymphoid organ formation and alveolar damage.. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2019, 129, 2514-2526, 10.1172/JCI125044.

- Lucy A. Truman; Kevin L. Bentley; Elenoe C. Smith; Stephanie A. Massaro; David G. Gonzalez; Ann M. Haberman; Myriam Hill; Dennis Jones; Wang Min; Diane S. Krause; et al.Nancy H. Ruddle ProxTom Lymphatic Vessel Reporter Mice Reveal Prox1 Expression in the Adrenal Medulla, Megakaryocytes, and Platelets. The American Journal of Pathology 2012, 180, 1715-1725, 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.026.

- Susan J. Doh; Michael Yamakawa; Samuel M. Santosa; Mario Montana; Kai Guo; Joseph R. Sauer; Nicholas Curran; Kyu-Yeon Han; Charles Yu; Masatsugu Ema; et al.Mark I. RosenblattJin-Hong ChangDimitri T. Azar Fluorescent reporter transgenic mice for in vivo live imaging of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2018, 21, 677-698, 10.1007/s10456-018-9629-2.

- Esther Redder; Nils Kirschnick; Stefanie Bobe; René Hägerling; Nils Rouven Hansmeier; Friedemann Kiefer; Vegfr3-tdTomato, a reporter mouse for microscopic visualization of lymphatic vessel by multiple modalities. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0249256, 10.1371/journal.pone.0249256.