Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric disorder accompanied by deficits in cognitive and social skills. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is a lifelong phenomenon, with new neurons being formed in the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus. Impaired neurogenesis is associated with multiple behavioral disorders including Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. PTSD patients often present hippocampal atrophy and animal models clearly present impaired neurogenesis. Increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-17 is reported in PTSD patients, but its role in the pathophysiology of the diseases is unknown.

- interleukin-17

- neurogenesis

- post-traumatic stress disorder

- social behavior

1. Introduction

2. Current Insights

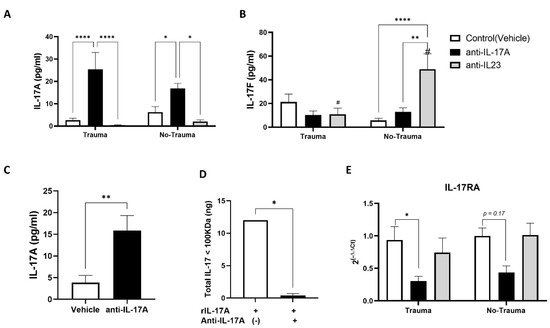

Figure 1. Antibody treatment affects IL-17 serum levels. Serum collected from mice at the end of the experiments (2.5 weeks post-trauma exposure) was analyzed for the protein levels of IL-17A (A) and IL-17F (B) using ELISA assay. Subgroups included pre-treatment with anti-IL17A antibodies (anti-IL17A), anti-IL-23 antibody (anti-IL-23), and vehicle injected animals (Control). (A) A graph presenting IL-17A serum levels detected by ELISA. (B) IL-17F detection of the same sub-treatment groups as described in (A). (C) Serum from control (vehicle treated animals) and anti-IL-17A treated animals was size filtered with 100 KDa cut-off membrane filter. The serum fraction containing protein complexes > 100 KDa was assayed for IL-17A levels using ELISA. The graph depicts the resulted concentrations. (D) A graph presenting the total amount of recombinant murine IL-17A that was filtered by a 100 KDa membrane filter with or without pre-incubation with anti-IL17A antibody (1:1 ratio). A total amount of 20 ng rIL-17A was filtered, and filtrate was analyzed by IL-17A ELISA with the total amount of protein calculated. (E) A graph presenting the relative gene expression for IL-17 receptor A (IL-17RA) in the hippocampus of animals from all treatment groups sacrificed 2.5 weeks post-trauma exposure, as detected by real-time PCR on hippocampal RNA. All data in the graphs is presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001,. Paired symbols represent statistical significance between the two corresponding groups: #p < 0.05.

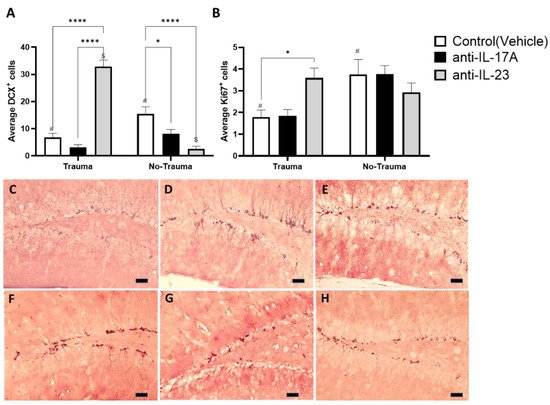

Figure 2. Exposure to trauma and antibody treatment affect hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampal neurogenesis was assessed by immunohistochemistry for proliferating neuro-progenitors (Ki67) and early differentiating neurons (DCX). (A) A graph presenting the average number of positive Ki67 cells in the sub-granular zone per hippocampal slide. (B) A graph presenting the average number of positive DCX cells in the granular cell layer per hippocampal slide. Representing micrographs of DCX- stained hippocampi from trauma exposed mice treated with anti-IL-17A (C), anti-IL-23 (D), control (vehicle) (E) and control (no trauma) mice treated anti-IL-17A (F), anti-IL-23 (G) and control (vehicle) (H). All data in the graphs is presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. Paired symbols represent statistical significance between the two corresponding groups: $p < 0.05, #p < 0.05. Scale bars represent 20 μm.

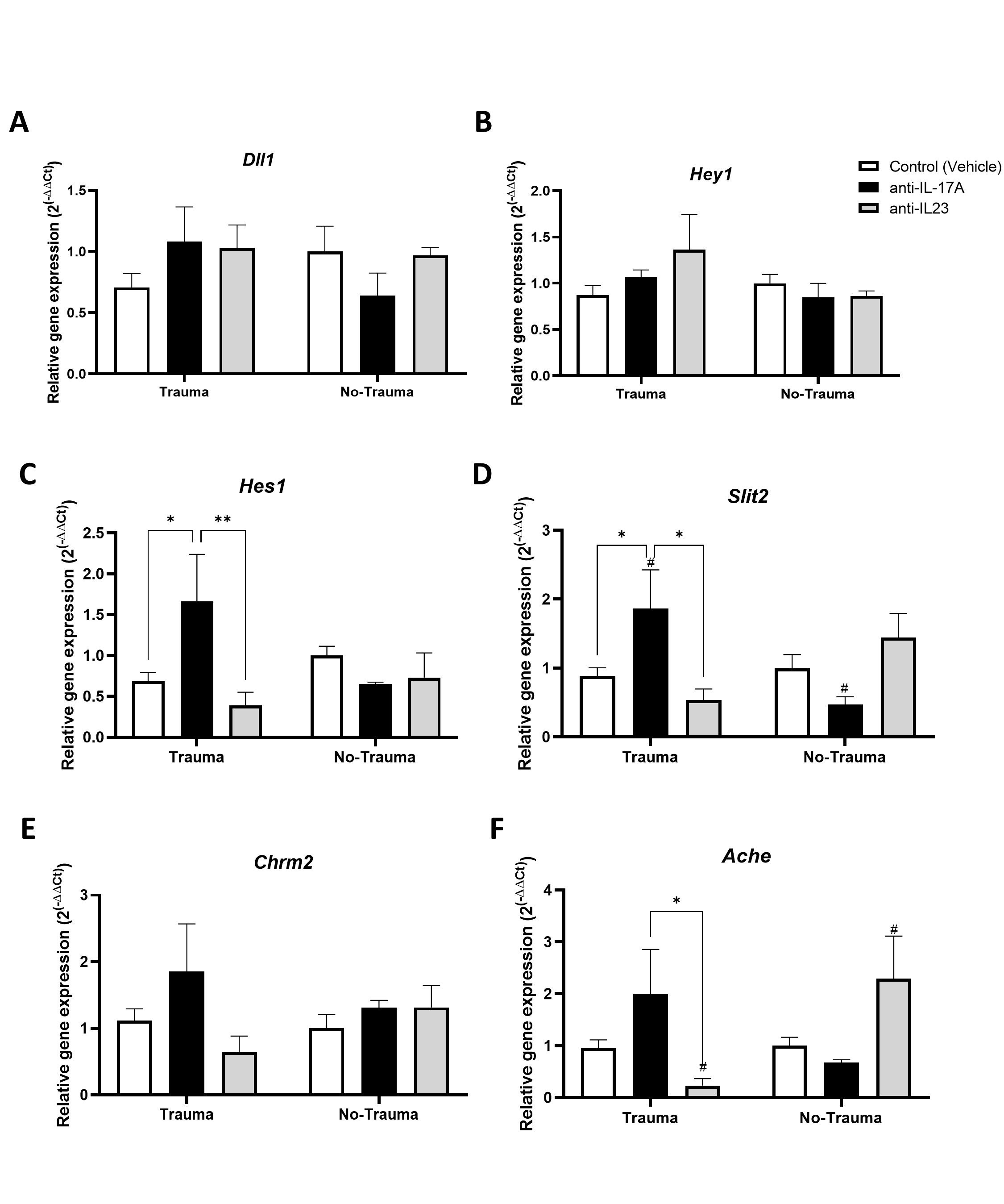

Figure 3. Exposure to trauma and antibody treatment affect hippocampal gene expression. Relative gene expression (2−∆ΔCT) detected by real time PCR performed on hippocampal RNA obtained from mice 2.5 weeks following exposure to trauma, for the following genes: (A) Dll1. (B) Hey1. (C) Hes1. (D) Slit2. (E) Chrm2 and (F) Ache. All data in the graphs is presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Paired symbols represent statistical significance between the two corresponding groups: #p < 0.05.

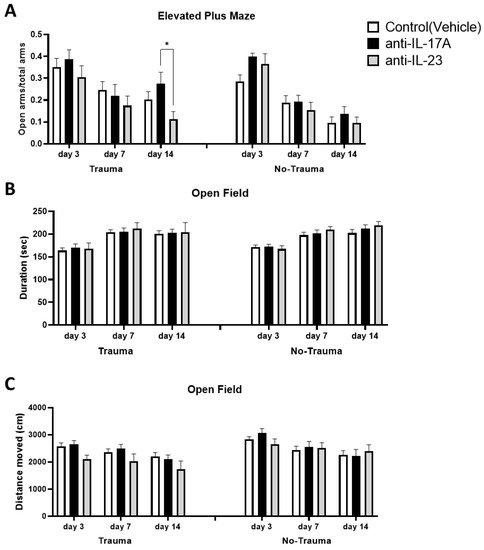

Figure 4. Exposure to trauma and antibody treatment do not affect general anxiety and locomotor activity. At days 3, 7, and 14 following the exposure to trauma, mice were subjected to elevated plus-maze and open field assays. General anxiety was measured in the elevated plus-maze assay where the preference of the tested mice for the open arms indicates for lower anxiety. (A) A graph presenting the ration of open arms duration to total arms duration of the various sub-groups. Similarly, the preference of the tested mice for the corners of the open field arena indicates for increased anxiety. (B) A graph presenting the duration the mice spent in the corners of the open field arena. (C) A graph presenting the total distance the mice travelled in the open field arena as an indication for locomotor activity. . All data in the graphs is presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05.

Figure 4. Exposure to trauma and antibody treatment do not affect general anxiety and locomotor activity. At days 3, 7, and 14 following the exposure to trauma, mice were subjected to elevated plus-maze and open field assays. General anxiety was measured in the elevated plus-maze assay where the preference of the tested mice for the open arms indicates for lower anxiety. (A) A graph presenting the ration of open arms duration to total arms duration of the various sub-groups. Similarly, the preference of the tested mice for the corners of the open field arena indicates for increased anxiety. (B) A graph presenting the duration the mice spent in the corners of the open field arena. (C) A graph presenting the total distance the mice travelled in the open field arena as an indication for locomotor activity. . All data in the graphs is presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05.

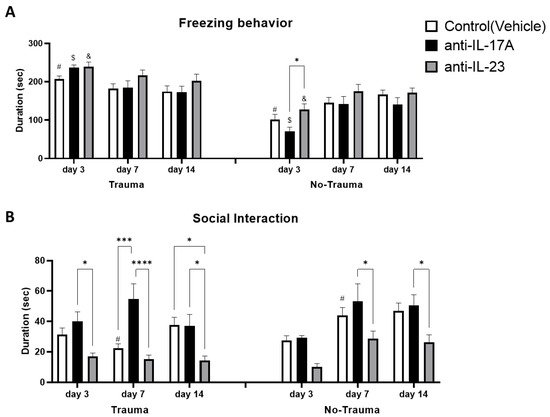

Figure 5. Exposure to trauma and antibody treatment affect trauma related behavior. At days 3, 7 and 14 following the exposure to trauma, mice were placed in the same arena in which they were exposed to the electric shock trauma for 5 min. Freezing behavior was measured as the duration of total inactivity by EthovisionTM tracking system. (A) A graph presenting inactivity duration in the different sub-groups. Social behavior was assessed as the duration of interaction between the tested mice and a novel unfamiliar mouse for 5 min, 3, 7- and 14-days following the exposure to trauma. (B) A graph presenting interaction duration in the different sub-groups. All data in the graphs is presented as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001. Paired symbols represent statistical significance between the two corresponding groups: $p < 0.05, &p < 0.05, #p < 0.05.

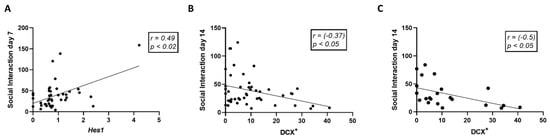

Figure 6. Social behavior correlates with hippocampal neurogenesis. Linear regression graphs depicting the correlation between Hes1 gene expression and social interaction duration at day 7 (A). Correlation between the number of DCX+ cells in the dentate gyrus and social interaction duration at day 14 for all experimental groups (B) and trauma-exposed groups only (C). Correlations were calculated using Pearson test.

References

- Björklund, A.; Lindvall, O. Self-repair in the brain. Nature 2000, 405, 892–893.

- Nakatomi, H.; Kuriu, T.; Okabe, S.; Yamamoto, S.-I.; Hatano, O.; Kawahara, N.; Tamura, A.; Kirino, T.; Nakafuku, M. Regeneration of Hippocampal Pyramidal Neurons after Ischemic Brain Injury by Recruitment of Endogenous Neural Progenitors. Cell 2002, 110, 429–441.

- Temple, S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 112–117.

- Seki, T. Understanding the Real State of Human Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis from Studies of Rodents and Non-human Primates. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 839.

- Duan, X.; Kang, E.; Liu, C.Y.; Ming, G.-L.; Song, H. Development of neural stem cell in the adult brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2008, 18, 108–115.

- Altman, J.; Das, G.D. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1965, 124, 319–335.

- Jurkowski, M.P.; Bettio, L.; Woo, E.K.; Patten, A.; Yau, S.-Y.; Gil-Mohapel, J. Beyond the Hippocampus and the SVZ: Adult Neurogenesis Throughout the Brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 576444.

- Berger, T.; Lee, H.; Young, A.; Aarsland, D.; Thuret, S. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Major Depressive Disorder and Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 803–818.

- Xie, F.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. Adult Neurogenesis Following Ischemic Stroke and Implications for Cell-Based Therapeutic Approaches. World Neurosurg. 2020, 138, 474–480.

- Lucassen, P.J.; Fitzsimons, C.P.; Salta, E.; Maletic-Savatic, M. Adult neurogenesis, human after all (again): Classic, optimized, and future approaches. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 381, 112458.

- Tanaka, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Singh, J.; Dalgard, C.L.; Wilkerson, M.; Zhang, Y. Region- and time-dependent gene regulation in the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex of a PTSD-like mouse model. Mol. Brain 2019, 12, 25.

- Egoswami, S.; Erodríguez-Sierra, O.; Ecascardi, M.; Epare, D. Animal models of post-traumatic stress disorder: Face validity. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 89.

- Samuelson, K.W. Post-traumatic stress disorder and declarative memory functioning: A review. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 346–351.

- Bremner, J.D. The Relationship Between Cognitive and Brain Changes in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1071, 80–86.

- Kikuchi, A.; Shimizu, K.; Nibuya, M.; Hiramoto, T.; Kanda, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Nomura, S. Relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder-like behavior and reduction of hippocampal 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine-positive cells after inescapable shock in rats. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 62, 713–720.

- Ishikawa, R.; Fukushima, H.; Frankland, P.W.; Kida, S. Hippocampal neurogenesis enhancers promote forgetting of remote fear memory after hippocampal reactivation by retrieval. eLife 2016, 5, e17464.

- Kheirbek, M.; Klemenhagen, K.C.; Sahay, A.; Hen, R. Neurogenesis and generalization: A new approach to stratify and treat anxiety disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1613–1620.

- O’Donovan, A.; Chao, L.L.; Paulson, J.; Samuelson, K.W.; Shigenaga, J.K.; Grunfeld, C.; Weiner, M.W.; Neylan, T.C. Altered inflammatory activity associated with reduced hippocampal volume and more severe posttraumatic stress symptoms in Gulf War veterans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 557–566.

- Zhou, J.; Nagarkatti, P.; Zhong, Y.; Ginsberg, J.P.; Singh, N.P.; Zhang, J.; Nagarkatti, M. Dysregulation in microRNA Expression Is Associated with Alterations in Immune Functions in Combat Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94075.

- Moshfegh, C.; Elkhatib, S.K.; Collins, C.W.; Kohl, A.J.; Case, A.J. Autonomic and Redox Imbalance Correlates With T-Lymphocyte Inflammation in a Model of Chronic Social Defeat Stress. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 103.

- Ojo, J.O.; Greenberg, M.B.; Leary, P.; Mouzon, B.; Bachmeier, C.; Mullan, M.; Diamond, D.M.; Crawford, F. Neurobehavioral, neuropathological and biochemical profiles in a novel mouse model of co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 213.

- Wacleche, V.S.; Landay, A.; Routy, J.-P.; Ancuta, P. The Th17 Lineage: From Barrier Surfaces Homeostasis to Autoimmunity, Cancer, and HIV-1 Pathogenesis. Viruses 2017, 9, 303.

- Tfilin, M.; Turgeman, G. Interleukine-17 Administration Modulates Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Improves Spatial Learning in Mice. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 69, 254–263.

- McGeachy, M.J.; Cua, D.J.; Gaffen, S.L. The IL-17 Family of Cytokines in Health and Disease. Immun. 2019, 50, 892–906.

- Jinna, S.; Strober, B. Anti-interleukin-17 treatment of psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2015, 27, 1–5.

- Finkelman, F.D.; Madden, K.B.; Morris, S.C.; Holmes, J.M.; Boiani, N.; Katona, I.M.; Maliszewski, C.R. Anti-cytokine antibodies as carrier proteins. Prolongation of in vivo effects of exogenous cytokines by injection of cytokine-anti-cytokine antibody complexes. J. Immunol. 1993, 151, 1235.

- Stein, M.L.; Villanueva, J.M.; Buckmeier, B.K.; Yamada, Y.; Filipovich, A.H.; Assa’Ad, A.H.; Rothenberg, M.E. Anti–IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy reduces eosinophil activation ex vivo and increases IL-5 and IL-5 receptor levels. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 1473–1483.e4.

- Hymowitz, S.G.; Filvaroff, E.H.; Yin, J.; Lee, J.; Cai, L.; Risser, P.; Maruoka, M.; Mao, W.; Foster, J.; Kelley, R.F.; et al. IL-17s adopt a cystine knot fold: Structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5332–5341.

- Chong, W.P.; Mattapallil, M.J.; Raychaudhuri, K.; Bing, S.J.; Wu, S.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Silver, P.B.; Jittayasothorn, Y.; et al. The Cytokine IL-17A Limits Th17 Pathogenicity via a Negative Feedback Loop Driven by Autocrine Induction of IL-24. Immunity 2020, 53, 384–397.e5.

- Kim, B.R.; Kim, M.; Yang, S.; Choi, C.W.; Lee, K.S.; Youn, S.W. Persistent expression of interleukin-17 and downstream effector cytokines in recalcitrant psoriatic lesions after ustekinumab treatment. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 876–882.

- Qiu, Z.-K.; Zhang, L.-M.; Zhao, N.; Chen, H.-X.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Mi, T.-Y.; Zhou, W.-W.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; et al. Repeated administration of AC-5216, a ligand for the 18kDa translocator protein, improves behavioral deficits in a mouse model of post-traumatic stress disorder. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 45, 40–46.

- Liu, Q.; Xin, W.; He, P.; Turner, D.; Yin, J.; Gan, Y.; Shi, F.-D.; Wu, J. Interleukin-17 inhibits Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7554.

- Anacker, C.; Hen, R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive flexibility—Linking memory and mood. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 335–346.

- Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Gao, C.; Sun, X. Astragaloside IV Exerts Cognitive Benefits and Promotes Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Stroke Mice by Downregulating Interleukin-17 Expression via Wnt Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 421.

- Sun, L.; Han, R.; Guo, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Sun, X.; Gao, C. Antagonistic effects of IL-17 and Astragaloside IV on cortical neurogenesis and cognitive behavior after stroke in adult mice through Akt/GSK-3β pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 1–18.

- Cui, L.; Xue, R.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Wan, Y.; Wu, W. Sleep deprivation inhibits proliferation of adult hippocampal neural progenitor cells by a mechanism involving IL-17 and p38 MAPK. Brain Res. 2019, 1714, 81–87.

- Zhang, Z.; Yan, R.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Kang, X.; Wang, H.; Huan, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Yang, S.; et al. Hes1, a Notch signaling downstream target, regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis following traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014, 1583, 65–78.

- Keohane, A.; Ryan, S.; Maloney, E.; Sullivan, A.; Nolan, Y.M. Tumour necrosis factor-α impairs neuronal differentiation but not proliferation of hippocampal neural precursor cells: Role of Hes1. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2010, 43, 127–135.

- Gobshtis, N.; Tfilin, M.; Fraifeld, V.E.; Turgeman, G. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells causes long-term alleviation of schizophrenia-like behaviour coupled with increased neurogenesis. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 26, 4448–4463.

- Borovcanin, M.M.; Janicijevic, S.M.; Jovanovic, I.P.; Gajovic, N.M.; Jurisevic, M.M.; Arsenijevic, N.N. Type 17 Immune Response Facilitates Progression of Inflammation and Correlates with Cognition in Stable Schizophrenia. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 926.

- Reed, M.D.; Yim, Y.S.; Wimmer, R.D.; Kim, H.; Ryu, C.; Welch, G.M.; Andina, M.; King, H.O.; Waisman, A.; Halassa, M.M.; et al. IL-17a promotes sociability in mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature 2020, 577, 249–253.

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Jiang, R.; Hong, X.; Peng, J.; Chen, W.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Huang, D.; Dai, H.; et al. Interleukin-17 activates and synergizes with the notch signaling pathway in the progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2021, 508, 1–12.

- Matsuzaki, T.; Yoshihara, T.; Ohtsuka, T.; Kageyama, R. Hes1 expression in mature neurons in the adult mouse brain is required for normal behaviors. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8251.