Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Emiliano Gallaga and Version 3 by Catherine Yang.

Tourism activity in general, with the heritage tourism sector in particular, represented the second inflow of foreign currency to Mexico in 2019 (pre-pandemic), with more than USD 24 million. According to local polls, the main purpose of travel is leisure. However, more than half of tourists (local and foreigner) who visit Mexico enjoy/visit an archaeological site, a museum, and/or a local community.

- cultural patrimony

- identity

- heritage

1. Introduction

Tourism activity in general, with the heritage tourism sector in particular, represented the second inflow of foreign currency to Mexico in 2019 (pre-pandemic) with more than USD 24 million [1][2][1,2]. Only the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) (National Institute of Anthropology and History) registered more than 26 million tourists who experienced the Zonas Arqueológicas (Z.A.) (Archaeological Zones) and the museums operated by INAH for the same period. Following from the above, it is shown that the heritage tourism sector is not only a vital axis for the national and local economy, but it can also be an important element for the cultural revitalization of communities. However, is this really happening? Did the local communities really enjoy the economic benefits from tourist activities? Did the members of the local communities have a voice and vote on the decision-making on how the heritage is being used as a tourist attraction? Did they feel related to that heritage? In most countries, archaeological activity is envisioned as an academic endeavor and normally, there is not a clear legal path on how or who has a right over the cultural heritage. Just in America, in the last couple of decades, several local and/or indigenous communities have raised their voice and made important legal and administrative changes on how the cultural patrimony needs to be handled and used (including tourism activities). For example, the native American communities passing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990 [3] or the members of the San Pedro de Atacama community in Chile who pushed the local museum to remove the human remains from the exhibition in 2006 and have some control on tourist activity [4]. However, what happens in a country where there is strong legislation on cultural heritage? Here, thwe researchers will describe the actual context of tourism vs. cultural heritage consumption in Mexico and how the local communities started to question the state’s control of it.

2. The Heritage Patrimony of Mexico

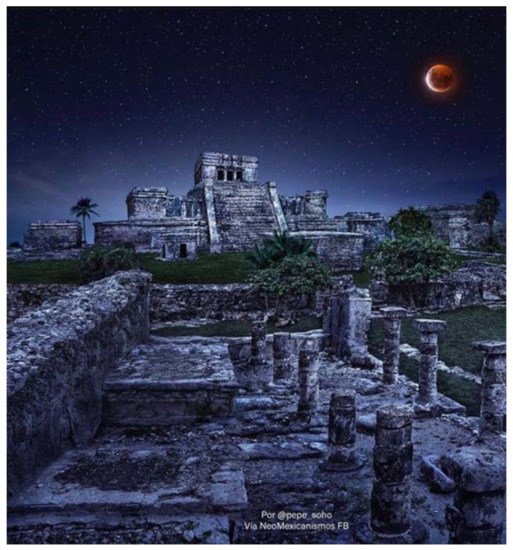

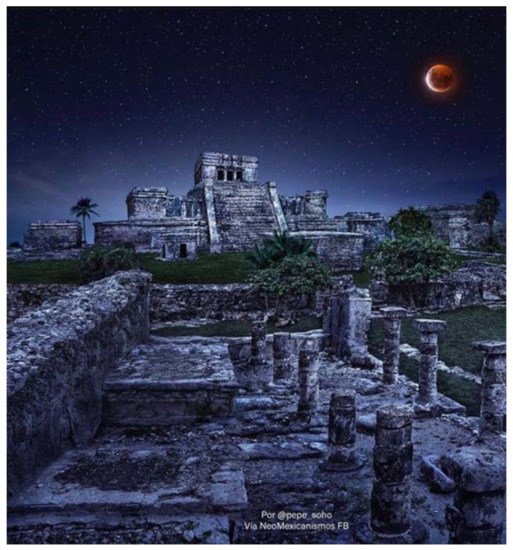

Sunbathing on a white sandy beach with crystal clear blue water, climbing an imposing Mayan pyramid in the middle of the Yucatan jungle, or just enjoying a tequila shot in a Mexican cantina, are some of the images most people have in the collective imagination about Mexico (Figure 13). This country is that and much more, and not for nothing is it among the 10 most visited places on earth. Mexico is not only known for its top places for the traditional tourism concept of the 3 big “S” (Sun, Sand, and Sea) such as Cancun, Los Cabos, or Nuevo Vallarta, where millions of tourists enjoy their vacations. They do not only stay there but travel around, enjoying the cultural and natural wonders of the country, making natural and heritage tourism the second activity of importance of this economic enterprise. On one hand, the great geographical diversity of the country with jungles, forests, beaches, mountains, volcanos, or deserts, make it an ideal place for nature-loving tourists. On the other hand, the most and great cultural diversity Mexico had to offer with a tangible and intangible cultural heritage make it a “must visit” country. Just to have a better idea, Mexico has until today 35 nominations for World Heritage and 10 Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity nominations by the UNESCO [5][6][7][36,37,38]. It is important to mention that this patrimony is the combination of the past and present of their culture in general and mainly those of indigenous communities in particular, who continue to preserve and maintain the local cultures alive. However, how does Mexico use, preserve, and research its cultural heritage?

Figure 13. Photographic composition at the archaeological site of Tulum, Mexico (photo by @pepe_soho) [8].

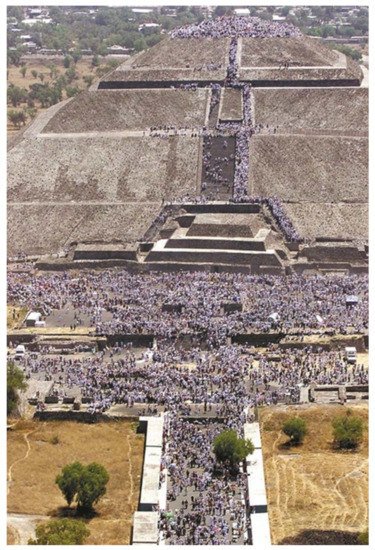

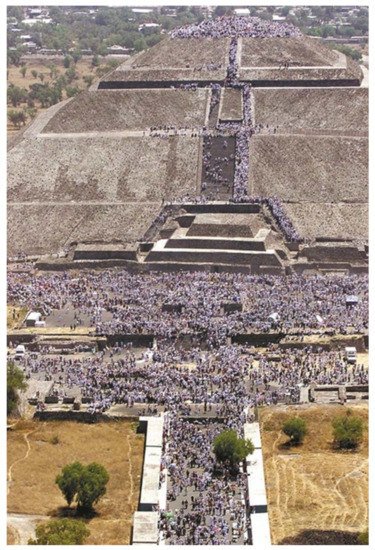

One of the major tourist attractions of Mexico is its pre-Hispanic and colonial heritage (Figure 24). Unlike other countries, the research, protection, and dissemination of the paleontological, archaeological, and historical heritage of Mexico only correspond by law to the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). However, some other educational institutions such as Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (UADY), Universidad Autónoma de Veracruz (UAV), and Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas (UAZ), to name a few, contribute to these worthy tasks. INAH, as well as other cultural and educational institutions, were made just after the turbulent years of the Mexican revolution, with the main task to help unite the country, provide a free and high standards education, have research institutions, and most importantly, build a Mexican state image. With this idea in mind, General Lazaro Cardenas, president of Mexico at the time, created INAH on February 13 1938 [9][10][11][12][40,41,42,43]. Because INAH is a national-level institution that covers all academic aspects concerning cultural heritage (state representation, research, restoration, museography, dissemination, archaeological record, storage rooms, laboratories) as well as its administration, any intervention of cultural heritage is regulated by it. In addition, in the specific case of archeology, every project, no matter how small or large it may be, has to go through an evaluation within the Archeology Council. What is the cultural patrimony in custody by INAH? From a rough estimation that establishes around 400–450 thousand archaeological sites in Mexico, nearly 40,000 of them are registered archaeologically; from the colonial time, 111,165 historical monuments are registered, from which 83,000 are civil properties. In museums and storage rooms is held more than 20,000,000 material objects and more than 3000 altarpieces exist in the churches’ country. In addition, 31 INAH Centers exist throughout the Mexican Republic (one per each state of the Republic, who are in charge of the local research and protection of the cultural patrimony). However, from the total of archaeological sites registered, only 194 Archaeological Zones are open to the public nationwide, and INAH operated and maintain 162 museums (national, regional, local, site, and community) as well. It is important to mention that archaeological sites are federal areas controlled by the federal government, not by the state or the community that holds them.

Figure 24. Spring equinox celebration in Teotihuacán that attracts thousands of people, many dressed in white with a red scarf or another accessory. Here, tourists try to access the top section of the Sun Pyramid (photo: ARCHIVO EL UNIVERSAL).

Almost all the research, preservation, and diffusion of the pre-Hispanic heritage of Mexico is done by INAH and paid by and for by the Federal Government. Although there is a strong academic standard to it, thwe researchers as as Mexican archaeologists cannot deny that the work the researchers we perform has a collateral result and that it is a tourist attraction. In the collective imagination of the members of a community where a new archaeological site had been discovered and worked, members think it is meant to burst the local economy. However, first, it is very difficult to open a new archaeological site to the public. A good portion of the site had to be explored archaeologically and that area prepared for tourist visits, the land where the site has to be federal, a minimal of facilities have to be built (such as bathrooms, storage room, ticket office, walking trails, and/or explanatory displays about the site), economic resources for its operation have to be found and allocated, and finally, only the president of Mexico can sign and authorize is opening. In addition, because INAH is a federal government agency and of the way this institute has been created, all the revenues from it go directly to the federal government, not to the local community. The only resources the community enjoys are a minimal set of jobs that the site needs to operate, such as custodians, cleaning personnel and administrative positions that only benefit a small percentage of the community—a situation that has been noted to create social inequalities among the members of the community. Sometimes, the tension breaks into a violent scenario, such as the one in September of 2008, when members of the local community of Ejido Miguel Hidalgo invade the Z.A. of Chinkultik, Chiapas to take control of it under the argument that the revenues from it had to be for the community. After a violent clash with the local and federal police, INAH gained control of the site but negotiated a rotation system of the job positions at the site every six months so more members of the community could benefit from it, and not only a handful.

The fee to enter Mexican archaeological sites are among the cheapest around the globe. To enter the site of Teotihuacan, for example, the general admission is MXN 80 (less than USD 4). On top of that, there are many exceptions to enter free, such as being a student/teacher enrolled in Mexico or over 65 years old, and admission is also free to all Mexicans on weekends. It is important to mention that for INAH, the diffusion of Mexican heritage is more important than its economic revenue. As a reminder, thwe researchers mentioned that 80% of tourists who enter these sites are local. Therefore, there is not a lot of direct revenue from this heritage attraction. On average, from the over 190 Z.A. open in Mexico, 10–15% of them generate revenue. On top of that is the administrative cost of operation for the sites (light, services, salaries, insurance, supplies, maintenance, and research operation cost), resources that came directly from the federal government, not from the site revenues. In the end, it does not matter if the site earns revenues or not—the federal government is in charge; but once again, for INAH, the importance is the diffusion of the Mexican heritage and not its revenue. This is also not a vision shared by the local states, such as Yucatan, where they build service tourist units (parador turistico) in the state territory just in front of the archaeological sites and charge for passage through it, and they do not have all the exceptions INAH had [13][44].

3. Archaeological Attractions Marketing

As has been shown, Mexican heritage tourism is not only an important economic enterprise for the country but is also controlled by the federal state through INAH. According to constitutional law, not only is archaeological academic activity regulated by INAH, but INAH also administrates the archaeological and colonial Mexican heritage. Very few countries around the globe have such strict regulations on their national heritage.

The sites that have been successful, economically speaking, are because the community realizes that the richness of the sites is not the direct revenue from it but the indirect revenue. That is to say, the tourist needs to be transported to the site, needs to eat and sleep somewhere, and wants to buy something, and the community does not have to depend only on the archaeological site as the only tourist attraction (diversification is key). When the community fulfills those needs, the distribution of tourists and its benefits is wider. However, there is also the case that some groups or local mafias take control of such tourism services like taxis or transport organizations; in this case, once again, only a handful of members of the community benefit from the tourism activity. From a legal standpoint, there is not a chance that the local community benefits directly from the archaeological site because this is directly controlled and administrated by INAH. However, there have been some examples. The only case that thwe researchers know in which a community got some direct benefit from an archaeological site is Chinkultik, Chiapas, when after a violent clash with the federal government and negotiations with INAH officials, the ejido Miguel Hidalgo received some job benefits. In other, non-violent examples, local communities obtain a local community museum where they not only display their heritage in conjunction with the “experts” but also have a community space to sell local artesanias (handicrafts) (but no direct control of the site). It is important to mention that these actions are more a personal battle by the archaeologist who works at that site and deals with the local communities’ interests (such as the Z.A. of Atzompa and Monte Alban, Oaxaca) [14][15][45,46].

Alternatively, there is a particular case where there is an unwanted tolerance of INAH officials to the local vendors to sell inside the archaeological sites such as Chichen Itza or Palenque, just to mention a few. This specific context had two sides: the illegal vendors endanger the conservation of the archaeological site and its surroundings are one side of the coin. On the other hand, because most tourists arrive at the site by bus directly to the site, the tourist does not have contact with the outside population; therefore, if the illegal vendor does not catch the tourist inside, they do not sell. Until today, there is no real solution to the problem; vendors are still inside the sites, and INAH does not want to take legal action (having all the laws in favor) but does not want to make a bigger community problem. Besides that, every year there are more illegal vendors inside, a good percentage of the vendors are not even from the local community, and very few sell local artesanias (handicrafts).