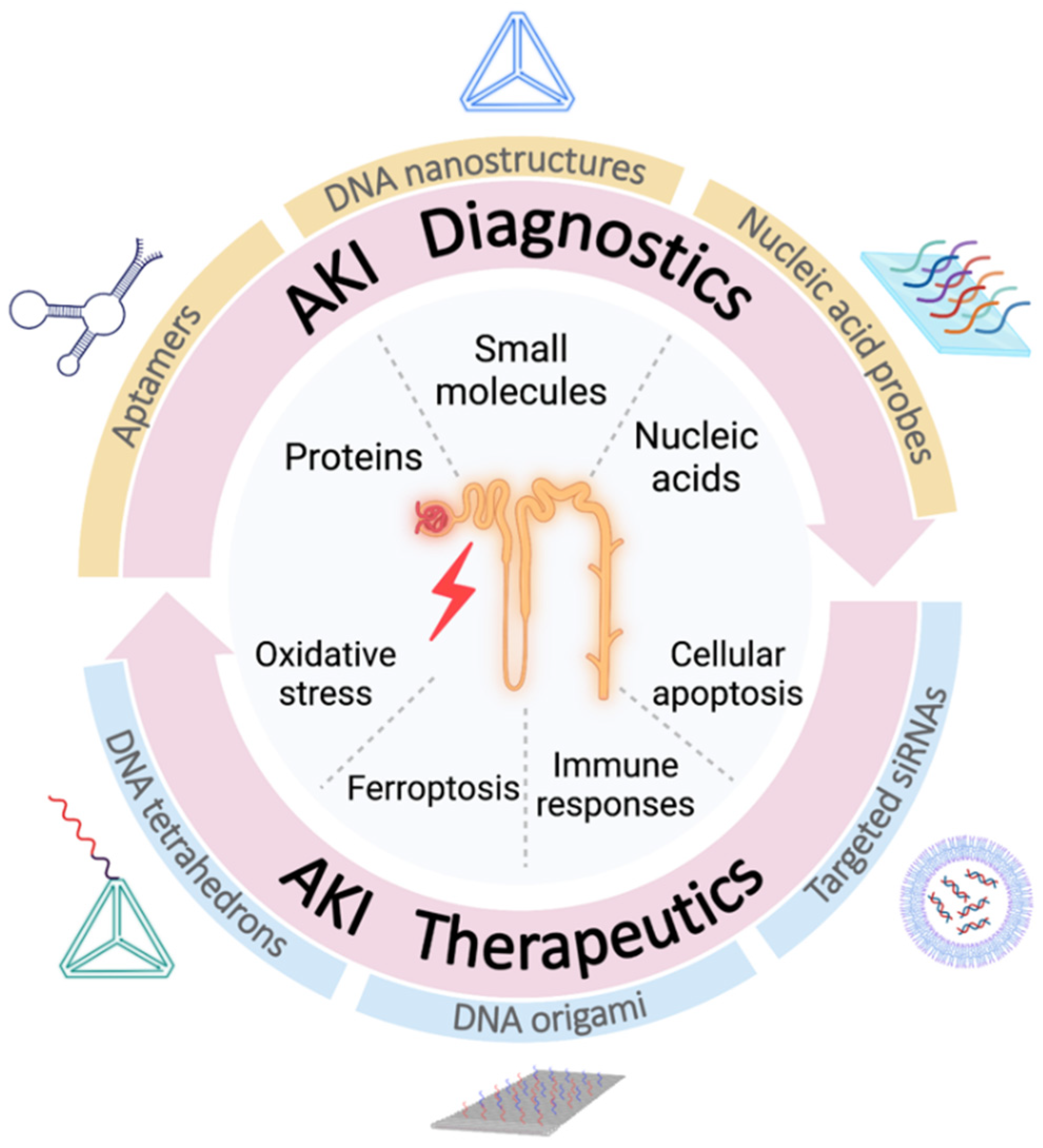

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a clinical syndrome characterized by an abrupted decline in renal function due to miscellaneous factors, such as rapid volume depletion, acute infection, nephrotoxic medicines and so on, leading to a retention of nitrogen wastes and creatinine accompanied by electrolyte disturbances and acid-base imbalance. Owing to the predictable base-pairing rule and highly modifiable characteristics, nucleic acids have already become significant biomaterials for nanostructure and nanodevice fabrication, which is known as nucleic acid nanotechnology. In particular, its excellent programmability and biocompatibility have further promoted its intersection with medical challenges. Lately, there have been an influx of research connecting nucleic acid nanotechnology with the clinical needs for renal diseases, especially AKI.

- nucleic acid nanotechnology

- AKI

- aptamer

- framework nucleic acids

- diagnosis

- targeted therapy

- biomarkers

1. Introduction

2. Diagnostics of AKI Based on Nucleic Acid Nanotechnology

|

Diagnostic Targets |

Type of Receptor |

Type of Surface or Electrodes |

Methods |

Samples |

LOD |

Range of Detection |

Refs |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Proteins |

NGAL |

NGAL antibody and DNA aptamer |

/ |

ELAA |

Buffer and Human AKI urine |

30.45 ng mL−1 |

125~4000 ng mL−1 |

[19] |

|

FAM-labelled DNA aptamer |

PDANS |

Fluorescence detection and DNase I-aided amplification |

HK-2 cells and Mice AKI urine |

6.25 pg mL−1 |

12.5~400 pg mL−1 |

[20] |

||

|

DNA aptamer |

GNP-modified biochip |

SWV |

Buffer |

0.07 pg mL−1 |

0.1~10 pg mL−1 |

[21] |

||

|

Redox reporter-modified DNA aptamer |

Gold electrodes |

SWV |

Artificial and Human urine |

2 and 3.5 nM |

Covers 2~32 nM |

[22] |

||

|

DNA aptamer |

AgNP IDE |

EIS |

Buffer and Artificial urine |

10 and 3 nM |

3~30 and 3~300 nM |

[23] |

||

|

RNA aptamer |

Microcantilever sensor |

Differential interferometry |

Buffer |

96 ng mL−1 |

Covers 100~3000 ng mL−1 |

[24] |

||

|

CysC |

DNA-linked antibody pair |

AuNP-functionalized Fe3O4 and G/mRub |

ECL measurement and DNA strand displacement-mediated amplification |

Buffer and Human serum |

0.38 fg mL−1 |

1.0 fg mL−1~10 ng mL−1 |

[25] |

|

|

FAM-labelled DNA aptamer |

GO |

Fluorescence detection and DNase I-aided amplification |

Buffer and Mice AKI urine |

0.16 ng mL−1 |

0.625~20 ng mL−1 |

[26] |

||

|

CysC antibody and DNA aptamer |

/ |

Competitive ELASA |

Buffer and Human serum |

216.077 pg mL−1 |

/ |

[6] |

||

|

CysC antibody and DNA aptamer |

/ |

Quantitative fluorescence LFA |

Buffer and Human urine |

0.023 μg mL−1 |

0.023~32 μg mL−1 |

[27] |

||

|

RBP4 |

DNA aptamer |

Gold chip |

SPR |

Artificial serum |

1.58 µg mL−1 |

/ |

[28] |

|

|

Albumin |

Cy5-labelled DNA aptamer |

GO |

Fluorescence detection |

Human urine and human serum |

0.05 µg mL−1 |

0.1~14.0 µg mL−1 |

[29] |

|

|

DNA aptamer |

Magnetic beads |

DPV aided with methylene blue solution |

Artificial and Human urine |

0.93~1.16 µg mL−1 (pH-related) |

10~400 µg mL−1 |

[30] |

||

|

Small molecules |

Urea |

DNA aptamer |

AuNP |

Colorimetric detection |

Milk sample |

20 mM |

20~150 mM |

[31] |

|

DNA aptamer |

CNTs/NH2-GO |

DPV |

Buffer and Human urine |

370 pM |

1.0~30.0 nM and 100~2000 nM |

[32] |

||

|

Nucleic acids |

miR-21 |

DNA probes |

Magnetic beads |

ECL measurement and HCR-mediated amplification |

Buffer and Human AKI urine |

0.14 fM |

1 fM~1 nM |

[33] |

|

DNA probes |

/ |

ECL measurement TMSD- and DNA NCs-aided amplification |

Buffer and Cell lines |

0.65 fM |

1 fM~100 pM |

[34] |

||

|

miR-16-5p |

DNA probes |

Capped gold nanoslit |

SPR |

Human AKI urine |

17 fM |

Up to nanomolar |

[35] |

|

Cys C, cystatin C; RBP4, retinol binding protein 4; LOD, limit of detection; ELAA, enzyme-linked aptamer analysis; FAM, 5-carboxyfluorescein; PDANS, polydopamine nanosphere; HK-2, human kidney 2 cells; GNP, graphene nanoplatelets; SWV, square wave voltammetry; AgNP, silver nanoparticle; IDE, interdigitated electrode; EIS, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy; AuNP, gold nanoparticle; G/mRub, monolayer rubrene functionalized graphene composite; ECL, electrochemiluminescence; GO, graphene oxide; ELASA, enzyme-linked aptamer sorbent assay; LFA, lateral flow assay; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; Cy5, cyanine 5; DPV, differential pulse voltammetry; CNT, carbon nanotubes; NH2-GO, amine-functionalized graphene oxide; HCR, hybridization chain reaction; TMSD, toehold-mediated strand displacement; DNA NCs, DNA nanoclews.

3. Therapeutic Approaches of AKI Based on Nucleic Acid Nanotechnology

3.1. Therapeutics Targeting Oxidative Stress

3.2. Therapeutics Targeting Ferroptosis

3.3. Therapeutics Targeting Immune Responses

3.4. Therapeutics Targeting p53-Related Cellular Apoptosis

References

- Bellomo, R.; Kellum, J.A.; Ronco, C. Acute Kidney Injury. Lancet 2012, 380, 756–766.

- Lameire, N.H.; Bagga, A.; Cruz, D.; De Maeseneer, J.; Endre, Z.; Kellum, J.A.; Liu, K.D.; Mehta, R.L.; Pannu, N.; Van Biesen, W.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury: An Increasing Global Concern. Lancet 2013, 382, 170–179.

- Hoste, E.A.J.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Bellomo, R.; Cely, C.M.; Colman, R.; Cruz, D.N.; Edipidis, K.; Forni, L.G.; Gomersall, C.D.; Govil, D.; et al. Epidemiology of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Patients: The Multinational AKI-EPI Study. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 41, 1411–1423.

- Hoste, E.A.J.; Kellum, J.A.; Selby, N.M.; Zarbock, A.; Palevsky, P.M.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Goldstein, S.L.; Cerdá, J.; Chawla, L.S. Global Epidemiology and Outcomes of Acute Kidney Injury. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 607–625.

- Baxmann, A.C.; Ahmed, M.S.; Marques, N.C.; Menon, V.B.; Pereira, A.B.; Kirsztajn, G.M.; Heilberg, I.P. Influence of Muscle Mass and Physical Activity on Serum and Urinary Creatinine and Serum Cystatin C. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2008, 3, 348–354.

- Kooshki, H.; Abbaszadeh, R.; Heidari, R.; Akbariqomi, M.; Mazloumi, M.; Shafei, S.; Absalan, M.; Tavoosidana, G. Developing a DNA Aptamer-Based Approach for Biosensing Cystatin-c in Serum: An Alternative to Antibody-Based Methods. Anal. Biochem. 2019, 584, 113386.

- Hertzberg, D.; Rydén, L.; Pickering, J.W.; Sartipy, U.; Holzmann, M.J. Acute Kidney Injury-an Overview of Diagnostic Methods and Clinical Management. Clin. Kidney J. 2017, 10, 323–331.

- Seeman, N.C. Nucleic Acid Junctions and Lattices. J. Theor. Biol. 1982, 99, 237–247.

- Seeman, N.C. DNA in a Material World. Nature 2003, 421, 427–431.

- Chen, T.; Ren, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Zhu, X. DNA Nanotechnology for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1671.

- Hu, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Gu, H.; Fan, C. DNA Nanotechnology-Enabled Drug Delivery Systems. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 6459–6506.

- Keller, A.; Linko, V. Challenges and Perspectives of DNA Nanostructures in Biomedicine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15818–15833.

- Jiang, S.; Ge, Z.; Mou, S.; Yan, H.; Fan, C. Designer DNA Nanostructures for Therapeutics. Chem 2021, 7, 1156–1179.

- Jiang, D.; Ge, Z.; Im, H.-J.; England, C.G.; Ni, D.; Hou, J.; Zhang, L.; Kutyreff, C.J.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. DNA Origami Nanostructures Can Exhibit Preferential Renal Uptake and Alleviate Acute Kidney Injury. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 865–877.

- Cho, E.J.; Lee, J.-W.; Ellington, A.D. Applications of Aptamers as Sensors. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2009, 2, 241–264.

- Trinh, K.H.; Kadam, U.S.; Song, J.; Cho, Y.; Kang, C.H.; Lee, K.O.; Lim, C.O.; Chung, W.S.; Hong, J.C. Novel DNA Aptameric Sensors to Detect the Toxic Insecticide Fenitrothion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 846.

- Trinh, K.H.; Kadam, U.S.; Rampogu, S.; Cho, Y.; Yang, K.-A.; Kang, C.H.; Lee, K.-W.; Lee, K.O.; Chung, W.S.; Hong, J.C. Development of Novel Fluorescence-Based and Label-Free Noncanonical G4-Quadruplex-like DNA Biosensor for Facile, Specific, and Ultrasensitive Detection of Fipronil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 127939.

- Meng, H.-M.; Liu, H.; Kuai, H.; Peng, R.; Mo, L.; Zhang, X.-B. Aptamer-Integrated DNA Nanostructures for Biosensing, Bioimaging and Cancer Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2583–2602.

- Hong, X.; Yan, H.; Xie, F.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Huang, H.; Yang, K.; Huang, S.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; et al. Development of a Novel SsDNA Aptamer Targeting Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin and Its Application in Clinical Trials. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 204.

- Hu, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Bai, X.; Lu, M.; Li, J.; Gu, L.; Liu, J.-H.; Yu, B.-Y.; et al. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of NGAL for the Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury via a Polydopamine Nanosphere/Aptamer Nanocomplex Coupled with DNase I-Assisted Recycling Amplification. Analyst 2020, 145, 3620–3625.

- Matassan, N.D.; Rizwan, M.; Mohd-Naim, N.F.; Tlili, C.; Ahmed, M.U. Graphene Nanoplatelets-Based Aptamer Biochip for the Detection of Lipocalin-2. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 9592–9599.

- Parolo, C.; Idili, A.; Ortega, G.; Csordas, A.; Hsu, A.; Arroyo-Currás, N.; Yang, Q.; Ferguson, B.S.; Wang, J.; Plaxco, K.W. Real-Time Monitoring of a Protein Biomarker. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 1877–1881.

- Rosati, G.; Urban, M.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Q.; de Carvalho Castro e Silva, C.; Bonaldo, S.; Parolo, C.; Nguyen, E.P.; Ortega, G.; Fornasiero, P.; et al. A Plug, Print & Play Inkjet Printing and Impedance-Based Biosensing Technology Operating through a Smartphone for Clinical Diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 196, 113737.

- Zhai, L.; Wang, T.; Kang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Shrotriya, P.; Nilsen-Hamilton, M. An RNA Aptamer-Based Microcantilever Sensor To Detect the Inflammatory Marker, Mouse Lipocalin-2. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8763–8770.

- Zhao, M.; Bai, L.; Cheng, W.; Duan, X.; Wu, H.; Ding, S. Monolayer Rubrene Functionalized Graphene-Based Eletrochemiluminescence Biosensor for Serum Cystatin C Detection with Immunorecognition-Induced 3D DNA Machine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 127, 126–134.

- Wang, B.; Yu, X.; Yin, G.; Wang, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, T. Developing a Novel and Simple Biosensor for Cystatin C as a Fascinating Marker of Glomerular Filtration Rate with DNase I-Aided Recycling Amplification Strategy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 203, 114230.

- Natarajan, S.; DeRosa, M.C.; Shah, M.I.; Jayaraj, J. Development and Evaluation of a Quantitative Fluorescent Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Cystatin-C, a Renal Dysfunction Biomarker. Sensors 2021, 21, 3178.

- Lee, S.J.; Youn, B.-S.; Park, J.W.; Niazi, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Gu, M.B. SsDNA Aptamer-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for the Detection of Retinol Binding Protein 4 for the Early Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 2867–2873.

- Chawjiraphan, W.; Apiwat, C.; Segkhoonthod, K.; Treerattrakoon, K.; Pinpradup, P.; Sathirapongsasuti, N.; Pongprayoon, P.; Luksirikul, P.; Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya, P.; Japrung, D. Sensitive Detection of Albuminuria by Graphene Oxide-Mediated Fluorescence Quenching Aptasensor. Spectrochim. Acta. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 231, 118128.

- Cheeveewattanagul, N.; Guajardo Yévenes, C.F.; Bamrungsap, S.; Japrung, D.; Chalermwatanachai, T.; Siriwan, C.; Warachit, O.; Somasundrum, M.; Surareungchai, W.; Rijiravanich, P. Aptamer-Functionalised Magnetic Particles for Highly Selective Detection of Urinary Albumin in Clinical Samples of Diabetic Nephropathy and Other Kidney Tract Disease. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1154, 338302.

- Kumar, P.; Ramulu Lambadi, P.; Kumar Navani, N. Non-Enzymatic Detection of Urea Using Unmodified Gold Nanoparticles Based Aptasensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 72, 340–347.

- Mansouri, R.; Azadbakht, A. Aptamer-Based Approach as Potential Tools for Construction the Electrochemical Aptasensor. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2019, 29, 517–527.

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sui, X.; Zhang, A.; Liu, X.; Lin, Z.; Chen, J. Highly Sensitive Homogeneous Electrochemiluminescence Biosensor for MicroRNA-21 Based on Cascaded Signal Amplification of Target-Induced Hybridization Chain Reaction and Magnetic Assisted Enrichment. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 344, 130226.

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, G.; Lian, G.; Luo, F.; Xie, Q.; Lin, Z.; Chen, G. Electrochemiluminescence Biosensor for MiRNA-21 Based on Toehold-Mediated Strand Displacement Amplification with Ru(Phen)32+ Loaded DNA Nanoclews as Signal Tags. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 147, 111789.

- Mousavi, M.Z.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lee, K.-L.; Lin, H.; Chen, H.-H.; Lin, Y.-F.; Wong, C.-S.; Li, H.F.; Wei, P.-K.; Cheng, J.-Y. Urinary Micro-RNA Biomarker Detection Using Capped Gold Nanoslit SPR in a Microfluidic Chip. Analyst 2015, 140, 4097–4104.

- Bonventre, J.V.; Yang, L. Cellular Pathophysiology of Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4210–4221.

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S.-K.; Wu, X.; He, D.; Cao, K.; Zhang, W. Emerging Role of Ferroptosis in Acute Kidney Injury. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8010614.

- Grivei, A.; Giuliani, K.T.K.; Wang, X.; Ungerer, J.; Francis, L.; Hepburn, K.; John, G.T.; Gois, P.F.H.; Kassianos, A.J.; Healy, H. Oxidative Stress and Inflammasome Activation in Human Rhabdomyolysis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 690–695.

- Kellum, J.A.; Chawla, L.S. Cell-Cycle Arrest and Acute Kidney Injury: The Light and the Dark Sides. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2016, 31, 16–22.

- Cartón-García, F.; Saande, C.J.; Meraviglia-Crivelli, D.; Aldabe, R.; Pastor, F. Oligonucleotide-Based Therapies for Renal Diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 303.

- Zhao, Y.; Pu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Song, X.; He, Z. Application of Nanotechnology in Acute Kidney Injury: From Diagnosis to Therapeutic Implications. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 233–251.

- Bosch, X.; Poch, E.; Grau, J.M. Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Kidney Injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 62–72.

- Panizo, N.; Rubio-Navarro, A.; Amaro-Villalobos, J.M.; Egido, J.; Moreno, J.A. Molecular Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutic Approaches to Rhabdomyolysis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2015, 40, 520–532.

- Zhang, Q.; Lin, S.; Wang, L.; Peng, S.; Tian, T.; Li, S.; Xiao, J.; Lin, Y. Tetrahedral Framework Nucleic Acids Act as Antioxidants in Acute Kidney Injury Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127426.

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA Damage: Mechanisms, Mutation, and Disease. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1195–1214.

- Loboda, A.; Damulewicz, M.; Pyza, E.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 System in Development, Oxidative Stress Response and Diseases: An Evolutionarily Conserved Mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3221–3247.

- Rothemund, P.W.K. Folding DNA to Create Nanoscale Shapes and Patterns. Nature 2006, 440, 297–302.

- Wei, B.; Dai, M.; Yin, P. Complex Shapes Self-Assembled from Single-Stranded DNA Tiles. Nature 2012, 485, 623–626.

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Li, N.; Dai, L.; Liu, Q.; Song, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Tian, J.; Ding, B.; et al. DNA Origami as an In Vivo Drug Delivery Vehicle for Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6633–6643.

- Malek, M.; Nematbakhsh, M. Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury; from Pathophysiology to Treatment. J. Ren. Inj. Prev. 2015, 4, 20–27.

- Chen, Q.; Ding, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Liu, X.; Song, H.; Zuo, X.; Fan, C.; Mou, S.; Ge, Z. Sequential Therapy of Acute Kidney Injury with a DNA Nanodevice. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 4394–4402.

- Chen, X.; Yu, C.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Iron Metabolism in Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 590226.

- Anandhan, A.; Dodson, M.; Schmidlin, C.J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, D.D. Breakdown of an Ironclad Defense System: The Critical Role of NRF2 in Mediating Ferroptosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 436–447.

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yi, B.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, K.; Zhang, W. VDR Activation Attenuate Cisplatin Induced AKI by Inhibiting Ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 73.

- Martin-Sanchez, D.; Ruiz-Andres, O.; Poveda, J.; Carrasco, S.; Cannata-Ortiz, P.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Ruiz Ortega, M.; Egido, J.; Linkermann, A.; Ortiz, A.; et al. Ferroptosis, but Not Necroptosis, Is Important in Nephrotoxic Folic Acid–Induced AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 218.

- Li, J.; Wei, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, M. Tetrahedral DNA Nanostructures Inhibit Ferroptosis and Apoptosis in Cisplatin-Induced Renal Injury. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 5026–5032.

- Wu, K.C.; Cui, J.Y.; Klaassen, C.D. Beneficial Role of Nrf2 in Regulating NADPH Generation and Consumption. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 123, 590–600.

- Li, W.; Wang, C.; Lv, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liu, S.; Gou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. A DNA Nanoraft-Based Cytokine Delivery Platform for Alleviation of Acute Kidney Injury. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 18237–18249.

- Cao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Niu, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, X.M.; Li, Q.; Lee, V.W.S.; et al. Potentiating Tissue-Resident Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells by IL-33 to Prevent Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 961.

- Lüthi, A.U.; Cullen, S.P.; McNeela, E.A.; Duriez, P.J.; Afonina, I.S.; Sheridan, C.; Brumatti, G.; Taylor, R.C.; Kersse, K.; Vandenabeele, P.; et al. Suppression of Interleukin-33 Bioactivity through Proteolysis by Apoptotic Caspases. Immunity 2009, 31, 84–98.

- Fridman, J.S.; Lowe, S.W. Control of Apoptosis by P53. Oncogene 2003, 22, 9030–9040.

- Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Huo, Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, F.; Dong, Z. Tubular P53 Regulates Multiple Genes to Mediate AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 2278.

- Caplen, N.J.; Parrish, S.; Imani, F.; Fire, A.; Morgan, R.A. Specific Inhibition of Gene Expression by Small Double-Stranded RNAs in Invertebrate and Vertebrate Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 9742.

- Molitoris, B.A.; Dagher, P.C.; Sandoval, R.M.; Campos, S.B.; Ashush, H.; Fridman, E.; Brafman, A.; Faerman, A.; Atkinson, S.J.; Thompson, J.D.; et al. SiRNA Targeted to P53 Attenuates Ischemic and Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1754–1764.

- Tang, W.; Chen, Y.; Jang, H.-S.; Hang, Y.; Jogdeo, C.M.; Li, J.; Ding, L.; Zhang, C.; Yu, A.; Yu, F.; et al. Preferential SiRNA Delivery to Injured Kidneys for Combination Treatment of Acute Kidney Injury. J. Control. Release 2022, 341, 300–313.

- Wang, Y.; Hazeldine, S.T.; Li, J.; Oupický, D. Development of Functional Poly(Amido Amine) CXCR4 Antagonists with the Ability to Mobilize Leukocytes and Deliver Nucleic Acids. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 729–738.

- Alidori, S.; Akhavein, N.; Thorek, D.L.J.; Behling, K.; Romin, Y.; Queen, D.; Beattie, B.J.; Manova-Todorova, K.; Bergkvist, M.; Scheinberg, D.A.; et al. Targeted Fibrillar Nanocarbon RNAi Treatment of Acute Kidney Injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8.

- Kaushal, G.P.; Haun, R.S.; Herzog, C.; Shah, S.V. Meprin A Metalloproteinase and Its Role in Acute Kidney Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2013, 304, F1150–F1158.

- Thai, H.B.D.; Kim, K.-R.; Hong, K.T.; Voitsitskyi, T.; Lee, J.-S.; Mao, C.; Ahn, D.-R. Kidney-Targeted Cytosolic Delivery of SiRNA Using a Small-Sized Mirror DNA Tetrahedron for Enhanced Potency. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 2250–2258.