In the plasma membrane and other cellular compartments (endosome/lysosome), sphingomyelin can be hydrolyzed to ceramide by sphingomyelinases. Ceramide generated by this pathway is further degraded into sphingosine by ceramidases. Shingosine can also be phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases to sphingosine-1-phosphate. Changes in the profiles of sphingomyelin and its metabolites ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) can result in a pathological condition triggered by accumulation or by altering cell signaling.

- diabetes

- angiotensin II-induced hypertension

- sphingomyelin

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

1.1. Sphingolipid Metabolism

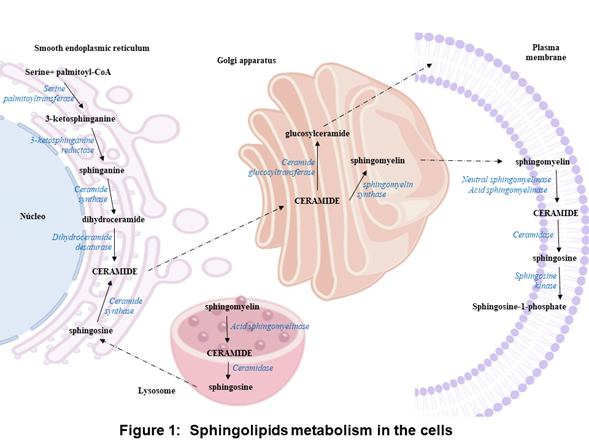

In thNume anabrolic pathway, sphingolipids synthesis begins in the endoplasmic reticulum with the condensation of L-serine and palmitoyl coenzyme A (CoA) to form 3-ketous human studies have shown that, in cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases, the profiles of sphinganineomyelin [1][2][3][4] byand serine palmitoyltransferase.its metabolites ceramide Subsequently[5][6][7][8][9][10][11], 3-ketosphinganosine reduct[12], ase is responsible for reducing 3-ketod sphinganine to sphinganine,osine-1-phosphate (S1P) which[13][14] can be acylated to form dihydroceramide by ceramide synthase. Finally, dihydroceramide is oxidized by a desaturase, which results in ceramide formationre altered (reduction or elevation) in the plasma, organs (liver and heart), and tissues (skeletal muscle and [1][2][3]. Ceramide is transported from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus and is converted into sphingomyelin by sphingomyelin synthase or glycosphingolipids byipose). Most of these studies focused on the determination of ceramide glucosyltransferasa. Sphingomyelin and complex glycosphingolipids can be transported to the plasma membrane (Figure 1) [3][4].

Iin plasma. However, it is necessary to perform preclinical the plasma membrane and other cell compartments, thestudies to determine the content of sphingomyelin can be hydrolyzed by sphingomyelinases (SMases) and release ceramide. Ceramide can be hydrolyzed by ceramidases (CDases) to form sphingosine, which can be phosphorylated by sphingosine kinase (SK) to generateand its bioactive metabolites in plasma and organs such as the brain, liver, heart, and kidney, because the sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) (Figure 1) [3][5][6][7][8][9]. S1P clipid metabolism imbalan bce cleavaged by the S1P lyase to a fatty aldehyde and phosphoethanolaminean be affected directly [10].or Alterinatively, S1P can be dephosphorylateddirectly in various organs.

On back to sphingosine by phosphataseshe other [11]. S1P chand, act as an intracellular second messenger or an extracellular ligand [12][13].

1.2. Classification of Sphingolipid Catabolism Enzymes

Accordchanges in the expression or activingty to the optimal pH for their activity, SMases are classified into acid, neutral, and alkaline. aSMase can be subclassified based oof the enzymes that participate in sphingolipid metabolism may explain the alterations in their cellular locatioprofile.

In into lysosomal aSMase (L-SMase) and secretory aSMase (S-SMase) [5][6]. Ceramhe anabolic pathway, the synthesidases also have been classified according to their optimal pH in acid, neutral, and alkaline [7][8]. Tw of sphingolipids stars by the condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA isoforms of nto 3-ketosphingosine kinases (SKs) have been identified, sphingosine kinase-1 and sphingosine kinase-2anine by the enzyme serine palmitoyl transferase, [9].

1.3. Genetic Diseases of Sphingolipid Catabolism Enzymes

Types A and B Niemann Pick disease is caust is followed by aSMase deficiency, which leads to organ dysfunction due to the accumulation of reduction yielding sphinganine. The sphingomyelin in various organs. Niemann Pick disease is inherited as recessive traits [14]. Faanine is acylate by ceramide synthase resulting dihydrbocer disease is a lysosomal storage disorder, it is causamides. Finally, ceramide is formed by mutations in the gene that encodes to aCDase, which lead to decreased aCDase activity and in turn, to the dehydrogenation of dihydroceramide by dihydroceramide accumulation and various pathological manifestations. Farber disease is inheridesaturase. The ceramide is converted in an autosomal recessive manner [15].

1.4. Sphingolipid Catabolism Enzymes as Therapeutic Targets in Cardiovascular Diseases

Nuto sphingomyerous human studies have shown that, in cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases, the profiles of lin by sphingomyelin synthase or glycosphingomyelin [16][17][18][19] anlipid its metabolitesy ceramide [20][21][22][23][24][25][26], sphingosine [27], and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) [28][29] are altered (reduction or elevation) in the plasma, organs (liver and heart), and tissues (skeletal muscle and adipose). Most of these studies focused on the determination of ceramide in plasma. However, it is necessary to perform preclinical studies to determine the content ofosyltransferase. In the catabolic pathway, sphingomyelinases (SMases) hydrolyzes sphingomyelin and its bioactive metabolites in plasma and organs such as the brain, liver, heart, and kidney, because theto release ceramide, which is hydrolyzed into sphingolipid metabolism imbalance can be affected directly or indirectly in various organs.

Csine and S1P by ceramidase (CDase) and sphainges in the expression or activity of the enzymes that participate in sphingolipid metabolism may explain theosine kinase (SK), respectively (Figure 1) alterations in their profile[15].

Concerning the expression at the mRNA level of the enzymes involved in the synthesis (serine palmitoyltransferase) and degradation of ceramide (SMase, CDase, and SK-1), the levels of these enzymes were increased in intra-abdominal adipose tissue and the myocardium of obese patients with or without type 2 diabetes [3016][3117].

Regarding enzyme activity, secretory SMase activity increased in the serum of patients with type 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, or acute coronary syndromes [3218][3319][3420]. In the adipose tissue of obese non-diabetic or diabetic patients, the activity of serine palmitoyltransferase, neutral and acid CDase (nCDase and aCDase) was increased, while the aSMase activity was decreased [227].

Changes in the profiles of sphingomyelin and its metabolites ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) can result in a pathological condition triggered by accumulation or by altering cell signaling.

In Therefore, drugs that modify the expression or activity of the enzymes involved in sphingolipid metabolism are attractive candidates for the treatment of cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases.

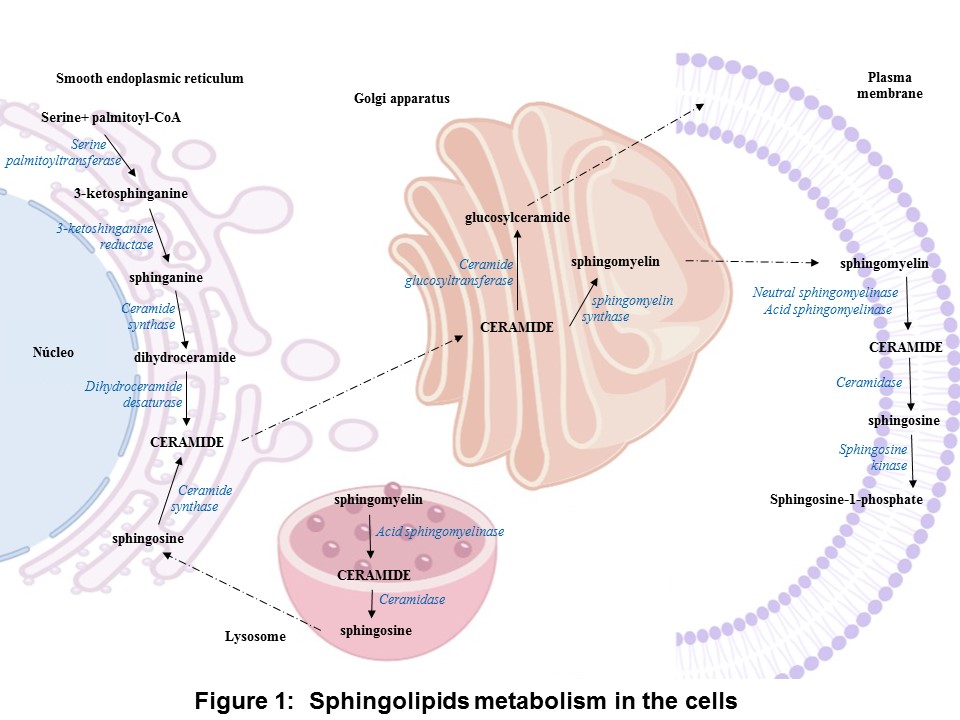

Resea previous study, researchers evaluated the sphingomyelin content and its metabolites in two experimental models: diabetic and hypertensive rats. The results show that, in the plasma and liver emonstrated that in the isolated perfused rat kidney of diabetic rats, sphingomyelin is increased; in the heart, ceramide; and in the kidney, S1P. Moreover, the vasoconstriction produced by S1P increases [21]. Add sphitingomyelin was observedonally, in the plasma and all evaluated organs of hypertensive rats, as well as increased ceramide and sphingosine in the heart, and increased S1P in the plasma, kidney, and heart (Figure 2isolated perfused rat kidney, angiotensin II (Ang II).

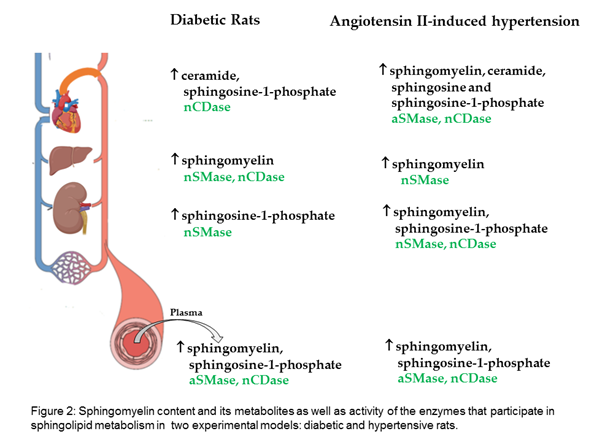

The results suggest that empagliflozin downregulates the interaction of the de novo pathway and the catabolic pathway of sphingolipid metabolism in diabetes, whereas, in Ang II-dependent hypertension, it only downregulates the sphingolipid catabolic pathway timulates ceramide formation via the activation of nSMase (Figure 32) [22].

2. Applications

2.1. Pharmacologic Inhibitors of Sphingolipid Catabolism Enzymes

Therefore use of pharmacologic inhibitors has been critical for the study of, drugs that modify the expression or activity of the enzymes involved in sphingolipid cametabolism enzymes as a potential therapeutic approach in respiratory (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis), neurodegenerative (Alzheimer’s disease),are attractive candidates for the treatment of cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic (obesity, diabetes), and cardiovascular disease (Table 1) [35][36][37][38]disease.

Table 1. Pharmacologic inhibitors of sphingolipid metabolism enzymes.

|

Enzyme |

Pharmacologic inhibitors |

|

aSMase |

Tricyclic antidepressants (desipramine, imipramine, and amitriptyline), SMA-7, and siramesine. |

|

nSMase |

scyphostatin, GW4869, and G11AG |

|

CDase |

N-Oleoylethanolamide (NOE), D-e-MAPP, LCL84, LCL204, LCL464, SABRAC, DP24c, KPB70, KPB67, Ceranib-2, Carmofur, and 17a. |

|

SK1 |

SKI-178, RB-005, PF-543, SLP7111228, Genzyme 51 |

|

SK2 |

(R)-FTY720-OMe, ABC294640, K145, SLP120701, SLR080811 |

2.2. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate and its Receptors as Drug Targets

Oneur of the biological applications of S1P has emerged with the discovery of the immunosuppressant drug. FTY720 acts as an S1P agonist when it is phosphorylated to FTY720-P. FTY720 can be phosphorylated by both SK1 and SK2, but SK2 has more affinity for the drug than SK1 [39]. FTY720-P results suggest that empagliflozin downregulates the interactis a potent agonist of four S1P receptors: S1P1, S1P3-5 [40][41].

2.3. Sphingomyelin and its Metabolites as Potential Therapeutic Targets of COVID-19 Disease

In tn of the sderum of patients with COVID-19 increase novo pathway and the concentration of serine palmitoyltransferase and acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase). Also, increased the concentration of dihydroatabolic pathway of sphingosine, dihydroceramide, ceramide, and sphingosine, and decrease sphingosine-1-phosphatelipid metabolism in [42][43]. Symptomatic COVID-19 patients exhibited a decrease in their serum sphingosine levels compared to asymptomatic patients levelse diabetes, whereas in Ang [44]. IInt-derestingly, sphingosine binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and prevents its interaction with the viral spike protein of SARS CoV 2 in human nasal epithelial cells [45]. Infectipendent hypertension, it on of human epithelial cells and different human cell lines with SARS-CoV-2 is reduced by treatment with amitriptyline and other antidepressants. In addition, the administration of anticeramide antibodies or neutral ceramidase also protects against SARS-CoV-2 infections [46]y downregulates the sphingolipid catabolic pathway (Figure 2).

References

- Merrill, A.H Jr. Characterization of serine palmitoyltransferase activity in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1983, 754, 284-91. https://doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(83)90144-3.Spijkers, L.J.; Van den Akker, R.F.; Janssen, B.J.; Debets, J.J.; De Mey, J.G.; Stroes, E.S.; Van den Born, B.J.; Wijesinghe, D.S.; Chalfant, C.E.; MacAleese, L.; Eijkel, G.B.; Heeren, R.M.; Alewijnse, A.E.; Peters, S.L. Hypertension is associated with marked alterations in sphingolipid biology: a potential role for ceramide. PLoS One. 2011; 6(7):218-17, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021817.

- Pewzner-Jung, Y.; Ben-Dor, S.; Futerman AH. When do Lasses (longevity assurance genes) become CerS (ceramide synthases)?: Insights into the regulation of ceramide synthesis. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 25001-5. https://doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600010200.Blachnio-Zabielska, A.U.; Koutsari, C.; Tchkonia, T.; Jensen, M.D. Sphingolipid Content of Human Adipose Tissue: Relationship to Adiponectin and Insulin Resistance. Obesity2012, 20, 2341–2347, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.126.

- Hannun, Y.A.; Luberto, C.; Argraves, K.M. Enzymes of Sphingolipid Metabolism: From Modular to Integrative Signaling. Biochemistry 2001; 40, 4893–4903. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi002836k.Barlovic, D.P.; Harjutsalo, V.; Sandholm, N.; Forsblom, C.; Groop, P-H. on behalf of the FinnDiane Study Group Sphingomyelin and progression of renal and coronary heart disease in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia2020, 63, 1847–1856,https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05201-9.

- Yeang, C.; Ding, T.; Chirico, W.J.; Jiang, X.C. Subcellular targeting domains of sphingomyelin synthase 1 and 2. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011, 8. https://doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-89.Jensen, P.N.;Fretts, A. M.; Hoofnagle, A. N.;Sitlani, C. M.; McKnight, B.; King, I. B.;Siscovick, D. S.;Psaty, B. M.;Heckbert, S. R.;Mozaffarian, D.;et al. Plasma Ceramides and Sphingomyelins in Relation to Atrial Fibrillation Risk: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Feb 18;9(4): e012853, https://doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012853.

- Goñi, F. M.; Alonso, A. Sphingomyelinases: enzymology and membrane activity. FEBS Lett 2002, 531, 38-46. https://doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03482-8.Haus, J.M.;Kashyap, S.R.;Kasumov, T.; Zhang, R.; Kelly, K.R.;Defronzo, R.A.; Kirwan, J.P. Plasma ceramides are elevated in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and correlate with the severity of insulin resistance. Diabetes2009, 58, 337–343.

- Shanbhogue, P.; Hannun, Y. A. Exploring the Therapeutic Landscape of Sphingomyelinases. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2020, 259, 19-47. https://doi: 10.1007/164_2018_179.Longato, L.; Tong, M.; Wands, J.R.; de la Monte, S.M. High fat diet induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance: Role of dysregulated ceramide metabolism. Res.2012, 42, 412–427, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1872-034x.2011.00934. x.

- Tani, M.; Igarashi, Y.; Ito M. Involvement of neutral ceramidase in ceramide metabolism at the plasma membrane and in extracellular milieu. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 36592-600. https://doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506827200.Błachnio-Zabielska, A.; Pułka, M.; Baranowski, M.; Nikołajuk, A.; Zabielski, P.; Górska, M.; Górski, J. Ceramide metabolism is affected by obesity and diabetes in human adipose tissue. Cell. Physiol.2012, 227, 550–557, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.22745.

- Mao, C.; Obeid, L. M. Ceramidases: regulators of cellular responses mediated by ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1781, 424-34. https://doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.002.Lopez, X.; Goldfine, A.; Holland, W.L.; Gordillo, R.; Scherer, P.E. Plasma ceramides are elevated in female children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab.2013, 26, 995–998, https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2012-0407.

- Pyne, S.; Adams, D. R.; Pyne, N.J. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and sphingosine kinases in health and disease: Recent advances. Prog Lipid Res 2016, 62, 93-106. https://doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.03.001.Mitsnefes, M.; Scherer, P.E.; Friedman, L.A.; Gordillo, R.; Furth, S.; A Warady, B.; CKiD Study Group; the CKiD study group Ceramides and cardiac function in children with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol.2014, 29, 415–422,https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-013-2642-1.

- Serra, M.; Saba, J.D. Sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase, a key regulator of sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling and function. Adv Enzyme Regul 2010, 50, 349-62. https://doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2009.10.024.Klein, R.L.; Hammad, S.M.; Baker, N.L.; Hunt, K.J.; Al Gadban, M.M.; Cleary, P.A.; Virella, G.; Lopes-Virella, M.F. Decreased plasma levels of select very long chain ceramide species Are associated with the development of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Metabolism2014, 63, 1287–1295https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2014.07.001.

- Pyne, S.; Lee, S. C.; Long, J.; Pyne, N.J. Role of sphingosine kinases and lipid phosphate phosphatases in regulating spatial sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling in health and disease. Cell Signal 2009, 21, 14-21. https://doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.08.008.de la Maza, M.P.;Rodriguez, J.M.; Hirsch, S.; Leiva, L.; Barrera, G.; Bunout, D. Skeletalmuscleceramidespecies in menwith abdominal obesity. Nutr. Health Aging2015, 19, 389–396.

- Van Brocklyn, J. R.; Lee, M.J.; Menzeleev, R.; Olivera, A.; Edsall, L.; Cuvillier, O.; Thomas, D.M.; Coopman, P. J.; Thangada, S.; Liu, C.H.; Hla, T.; Spiegel, S. Dual actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate: extracellular through the Gi-coupled receptor Edg-1 and intracellular to regulate proliferation and survival. J Cell Biol 1998, 142, 229-40. https://doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.229.Górska, M.; Dobrzyn, A.; Baranowski, M. Concentrations of sphingosine and sphinganine in plasma of patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Sci. Monit.2005, 11, CR35–CR38.

- Taha, T.A.; Argraves, K.M.; Obeid, L.M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors: receptor specificity versus functional redundancy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004, 1682, 48-55. https://doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.01.006.Deutschman, D.H.; Carstens, J.S.; Klepper, R.L.; Smith, W.S.; Page, M.; Young, T.R.; A Gleason, L.; Nakajima, N.; A Sabbadini, R. Predicting obstructive coronary artery disease with serum sphingosine-1-phosphate. Hear. J.2003, 146, 62–68,https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8703(03)00118-2.

- Schuchman, E. H.; Desnick, R.J. Types A and B Niemann-Pick disease. Mol Genet Metab 2017, 120, 27-33. https://doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.12.008.Kowalski, G.M.; Carey, A.L.; Selathurai, A.; Kingwell, B.A.; Bruce, C.R. Plasma Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Is Elevated in Obesity. PLoS ONE2013, 8, e72449, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072449.

- Yu, F.P.S.; Amintas, S.; Levade, T.; Medin, J.A. Acid ceramidase deficiency: Farber disease and SMA-PME. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2018, 13, 121. https://doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0845-z.Hannun, Y.A.; Luberto, C.; Argraves, K.M. Enzymes of Sphingolipid Metabolism: From Modular to Integrative Signaling. Biochemistry2001, 40, 4893–4903, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi002836k.

- Spijkers, L.J.; Van den Akker, R.F.; Janssen, B.J.; Debets, J.J.; De Mey, J.G.; Stroes, E.S.; Van den Born, B.J.; Wijesinghe, D.S.; Chalfant, C.E.; MacAleese, L.; Eijkel, G.B.; Heeren, R.M.; Alewijnse, A.E.; Peters, S.L. Hypertension is associated with marked alterations in sphingolipid biology: a potential role for ceramide. PLoS One 2011, 6, 218-17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021817.Baranowski, M.; Blachnio-Zabielska, A.; Hirnle, T.; Harasiuk, D.; Matlak, K.; Knapp, M.; Zabielski, P.; Górski, J. Myocardium of type 2 diabetic and obese patients is characterized by alterations in sphingolipid metabolic enzymes but not by accumulation of ceramide. Lipid Res.2010, 51, 74–80, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.m900002-jlr200.

- Blachnio-Zabielska, A.U.; Koutsari, C.; Tchkonia, T.; Jensen, M.D. Sphingolipid Content of Human Adipose Tissue: Relationship to Adiponectin and Insulin Resistance. Obesity 2012, 20, 2341–2347. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.126.Kolak, M.; Gertow, J.; Westerbacka, J.; Summers, A.S.; Liska, J.; Franco-Cereceda, A.; Orešič, M.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Eriksson, P.; Fisher, R.M. Expression of ceramide-metabolising enzymes in subcutaneous and intra-abdominal human adipose tissue. Lipids Heal. Dis.2012, 11, 115–115, https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511x-11-115.

- Barlovic, D.P.; Harjutsalo, V.; Sandholm, N.; Forsblom, C.; Groop, P-H. on behalf of the FinnDiane Study Group Sphingomyelin and progression of renal and coronary heart disease in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1847–1856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05201-9.Górska, M.; Barańczuk, E.; Dobrzyń, A. Secretory Zn2+-dependent Sphingomyelinase Activity in the Serum of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes is Elevated. Metab. Res.2003, 35, 506–507, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-41810.

- Jensen, P.N.; Fretts, A. M.; Hoofnagle, A. N.; Sitlani, C. M.; McKnight, B.; King, I. B.;Siscovick, D. S.; Psaty, B. M.; Heckbert, S. R.; Mozaffarian, D.; et al. Plasma Ceramides and Sphingomyelins in Relation to Atrial Fibrillation Risk: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9(4): e012853. https://doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012853.Doehner, W.; Bunck, A.C.; Rauchhaus, M.; von Haehling, S.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Cicoira, M.; Tschope, C.; Ponikowski, P.; Claus, R.A.; Anker, S.D. Secretory sphingomyelinase is upregulated in chronic heart failure: a second messenger system of immune activation relates to body composition, muscular functional capacity, and peripheral blood flow. Heart J. 2007, 28, 821–828.

- Haus, J.M.; Kashyap, S.R.; Kasumov, T.; Zhang, R.; Kelly, K.R.; Defronzo, R.A.; Kirwan, J.P. Plasma ceramides are elevated in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and correlate with the severity of insulin resistance. Diabetes 2009, 58, 337–343.Pan, W.; Yu, J.; Shi, R.; Yan, L.; Yang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Bai, Y.; Schuchman, H.; et al. Elevation of ceramide and activation of secretory acid sphingomyelinase in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Coron Artery Dis. 2014; 25(3):230-5, https://doi.org/10.1097/mca.0000000000000079.

- Longato, L.; Tong, M.; Wands, J.R.; de la Monte, S.M. High fat diet induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance: Role of dysregulated ceramide metabolism. Res 2012, 42, 412–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1872-034x.2011.00934. x.Bautista-Pérez, R.; Arellano, A.; Franco, M.; Osorio, H.; Coronel, I. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induced vasoconstriction is increased in the isolated perfused kidneys of diabetic rats. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr.2011, 94, e8–e11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2011.06.023.

- Błachnio-Zabielska, A.; Pułka, M.; Baranowski, M.; Nikołajuk, A.; Zabielski, P.; Górska, M.; Górski, J. Ceramide metabolism is affected by obesity and diabetes in human adipose tissue. Physiol 2012, 227, 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.22745.Bautista-Pérez, R.; Del Valle-Mondragón, L.; Cano-Martínez, A.; Pérez-Méndez, O.; Escalante, B.; Franco, M. Involvement of neutral sphingomyelinase in theangiotensin II signalingpathway. J. Physiol. Physiol.2015, 308, F1178–F1187, https:// doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00079.2014.

- Lopez, X.; Goldfine, A.; Holland, W.L.; Gordillo, R.; Scherer, P.E. Plasma ceramides are elevated in female children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2013, 26, 995–998. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2012-0407.

- Mitsnefes, M.; Scherer, P.E.; Friedman, L.A.; Gordillo, R.; Furth, S.; A Warady, B.; CKiD Study Group; the CKiD study group Ceramides and cardiac function in children with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol 2014, 29, 415–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-013-2642-1.

- Klein, R.L.; Hammad, S.M.; Baker, N.L.; Hunt, K.J.; Al Gadban, M.M.; Cleary, P.A.; Virella, G.; Lopes-Virella, M.F. Decreased plasma levels of select very long chain ceramide species Are associated with the development of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Metabolism 2014, 63, 1287–1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2014.07.001.

- de la Maza, M. P.; Rodriguez, J.M.; Hirsch, S.; Leiva, L.; Barrera, G.; Bunout, D. Skeletal muscle ceramide species in men with abdominal obesity. Nutr Health Aging 2015, 19, 389–396.

- Górska, M.; Dobrzyn, A.; Baranowski, M. Concentrations of sphingosine and sphinganine in plasma of patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Sci. Monit 2005, 11, CR35–CR38.

- Deutschman, D.H.; Carstens, J.S.; Klepper, R.L.; Smith, W.S.; Page, M.; Young, T.R.; A Gleason, L.; Nakajima, N.; A Sabbadini, R. Predicting obstructive coronary artery disease with serum sphingosine-1-phosphate. Hear J 2003, 146, 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8703(03)00118-2.

- Kowalski, G.M.; Carey, A.L.; Selathurai, A.; Kingwell, B.A.; Bruce, C.R. Plasma Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Is Elevated in Obesity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72449. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072449.

- Baranowski, M.; Blachnio-Zabielska, A.; Hirnle, T.; Harasiuk, D.; Matlak, K.; Knapp, M.; Zabielski, P.; Górski, J. Myocardium of type 2 diabetic and obese patients is characterized by alterations in sphingolipid metabolic enzymes but not by accumulation of ceramide. Lipid Res 2010, 51, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.m900002-jlr200.

- Kolak, M.; Gertow, J.; Westerbacka, J.; Summers, A.S.; Liska, J.; Franco-Cereceda, A.; Orešič, M.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Eriksson, P.; Fisher, R.M. Expression of ceramide-metabolising enzymes in subcutaneous and intra-abdominal human adipose tissue. Lipids Heal Dis 2012, 11, 115–115. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511x-11-115.

- Górska, M.; Barańczuk, E.; Dobrzyń, A. Secretory Zn2+-dependent Sphingomyelinase Activity in the Serum of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes is Elevated. Metab Res 2003, 35, 506–507. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-41810.

- Doehner, W.; Bunck, A.C.; Rauchhaus, M.; von Haehling, S.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Cicoira, M.; Tschope, C.; Ponikowski, P.; Claus, R.A.; Anker, S.D. Secretory sphingomyelinase is upregulated in chronic heart failure: a second messenger system of immune activation relates to body composition, muscular functional capacity, and peripheral blood flow. Heart J. 2007, 28, 821–828.

- Pan, W.; Yu, J.; Shi, R.; Yan, L.; Yang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Bai, Y.; Schuchman, H.; et al. Elevation of ceramide and activation of secretory acid sphingomyelinase in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Coron Artery Dis 2014; 25(3):230-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/mca.0000000000000079.

- Canals, D.; Perry, D.M.; Jenkins, R.W.; Hannun, Y.A. Drug targeting of sphingolipid metabolism: sphingomyelinases and ceramidases. Br J Pharmacol 2011, 163, 694-712. https://doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01279. x.

- Beckmann, N.; Sharma, D.; Gulbins, E.; Becker, K.A.; Edelmann, B. Inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase by tricyclic antidepressants and analogons. Front Physiol 2014; 5, 331. https://doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00331.

- Saied, E.M.; Arenz, C. Inhibitors of Ceramidases. Chem Phys Lipids 2016; 197, 60-8. https:// doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.07.009.

- Sanllehí, P.; Abad, J.L.; Casas, J.; Delgado, A. Inhibitors of sphingosine-1-phosphate metabolism (sphingosine kinases and sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase). Chem Phys Lipids 2016; 197, 69-81. https://doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.07.007.

- Billich, A.; Bornancin, F.; Dévay, P.; Mechtcheriakova, D.; Urtz, N.; Baumruker, T. Phosphorylation of the immunomodulatory drug FTY720 by sphingosine kinases. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 47408-15. https://doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307687200.

- Brinkmann, V.; Davis, M.D.; Heise, C.E.; Albert, R.; Cottens, S.; Hof, R.; Bruns, C.; Prieschl, E.; Baumruker, T.; Hiestand, P.; Foster, C.A.; Zollinger, M.; Lynch, K. R. The immune modulator FTY720 targets sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 21453-7. https:// 10.1074/jbc.C200176200.

- Brinkmann, V.; Lynch, K.R. FTY720: targeting G-protein-coupled receptors for sphingosine 1-phosphate in transplantation and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2002, 14, 569-575. https://doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00374-6.

- Torretta, E.; Garziano, M.; Poliseno, M.; Capitanio, D.; Biasin, M.; Santantonio, T.A.; Clerici, M.; Lo Caputo, S.; Trabattoni, D.; Gelfi, C. Severity of COVID-19 Patients Predicted by Serum Sphingolipids Signature. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 22; 22(19):10198. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910198.

- Marfia, G.; Navone, S.; Guarnaccia, L.; Campanella, R.; Mondoni, M.; Locatelli, M.; Barassi, A.; Fontana, L.; Palumbo, F.; Garzia, E.; Ciniglio Appiani, G.; Chiumello ,D.; Miozzo ,M.; Centanni, S.; Riboni, L. Decreased serum level of sphingosine-1-phosphate: a novel predictor of clinical severity in COVID-19. EMBO Mol Med. 2021 Jan 11;13(1):e13424. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202013424.

- Janneh, A.H.; Kassir, M.F.; Dwyer, C.J.; Chakraborty, P.; Pierce, J.S.; Flume, P.A.; Li H.; Nadig, S.N.; Mehrotra, S.; Ogretmen, B. Alterations of lipid metabolism provide serologic biomarkers for the detection of asymptomatic versus symptomatic COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 9;11(1):14232. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93857-7.

- Edwards, M.J.; Becker, K.A.; Gripp. B.; Hoffmann, M.; Keitsch, S.; Wilker, B.; Soddemann, M.; Gulbins, A.; Carpinteiro, E.; Patel, SH.; Wilson, G. C.; Pöhlmann, S.; Walter, S.; Fassbender, K.; Ahmad, S. A.; Carpinteiro, A.; Gulbins, E. Sphingosine prevents binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike to its cellular receptor ACE2. J Biol Chem. 2020 Nov 6;295(45):15174-15182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015249.

- Carpinteiro, A.; Edwards, M.J.; Hoffmann, M.; Kochs, G.; Gripp, B.; Weigang, S.; Adams, C.; Carpinteiro, E.; Gulbins, A.; Keitsch, S.; Sehl, C.; Soddemann, M.; Wilker, B.; Kamler, M.; Bertsch,T.; Lang, K.S.; Patel, S.; Wilson, G.C.; Walter, S.; Hengel, H.; Pöhlmann, S.; Lang, P.A.; Kornhuber ,J.; Becker KA.; Ahmad SA.; Fassbender K.; Gulbins E. Pharmacological Inhibition of Acid Sphingomyelinase Prevents Uptake of SARS-CoV-2 by Epithelial Cells. Cell Rep Med. 2020 Nov 17;1(8):100142. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100142.