Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 4 by Camila Xu.

Anxiety, depressive symptoms and stress have a significant influence on chronic musculoskeletal pain. Behavioral modification techniques have proven to be effective to manage these variables; however, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for an alternative to face-to-face treatment.

- telerehabilitation

- behavior

- depression

- anxiety

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken our lives and jeopardized the treatment of countless patients with chronic pain [1][2]. Chronic pain patients have shown a significant increase in their perceived pain in comparison with the pre-pandemic period [3], as well as an increase in depressive symptoms, anxiety, loneliness, tiredness and catastrophizing [3]. Nearly half of a sample of 2423 chronic pain patients had moderate to severe psychological distress [4]. The worsening of mental health in patients with chronic pain is not without consequences; these variables have been linked to higher pain catastrophizing, pain-related fear and avoidance, and a higher risk of misuse of opioids [5][6].

These patients need follow-up, a close relationship with health professionals and appropriate treatment, but social distancing prevents them from doing so [1]. Chronic pain patients had higher self-isolation than participants without pain during the pandemic [3]. Because it does not require being physically present, telerehabilitation, or the therapeutic use of technological devices, has been recommended for chronic pain management worldwide [2]. Over the last few decades, behavioral modification techniques (BMT) have showed to be effective in the management of psychological variables in chronic pain patients [7][8]. However, it is not clear if telematic BMT (e-BMT) is also effective to improve psychological variables and if it is as effective as in-person BMT. Some previous systematic reviews have assessed the effect of telerehabilitation based on BMT on variables such as pain intensity, disability, disease impact, physical function, pain-related fear of movement, and psychological distress [9][10][11][12], showing promising results.

2. Descriptions of the Studies

From the 749 studies initially detected, a total of 41 RCTs were included [13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53]. Researchers included 5018 participants with a mean age ranging from 33.7 to 65.8 years. The patients were mostly women (N = 3631, 72.4%) diagnosed with chronic back pain [19][24][44][51][52], chronic low back pain [13][27], unspecific chronic pain [15][23][25][28][31][39][40][41][42][43][45][46][47][48][53], fibromyalgia [14][18][20][21][30][35][38], headache [16][32][33][50], rheumatic disorders [17][29][34][36], or others [22][26][37].

The studies compared online cognitive-behavioral therapy [14][15][17][18][19][26][27][31][35][42][44][51][52][53], acceptance and commitment therapy [28][30][42][43][45][48], self-management [24][31][34][38][39][40][41][49], mindfulness therapy [33][37][42][44][48], or other e-BMT [13][16][20][21][22][25][29][32][36][46][47][50], against most frequently waiting list [15][16][18][20][23][26][28][29][32][34][36][40][43][44][46][47][49][51][52][53], usual care [14][17][19][21][24][27][30][31][33][35][38][39][41][42][45][50], or in-person intervention [22][35][48]. The intervention duration ranged between a single day [37] and 6 months [13][22][34][38][50]. The details of the interventions using the Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) [54].

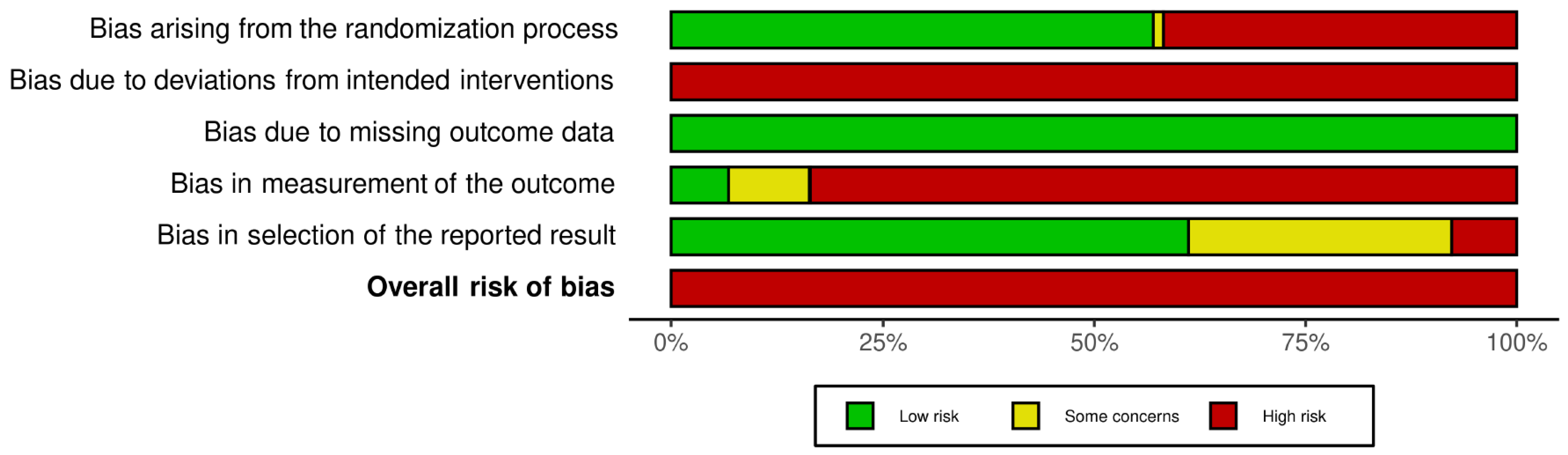

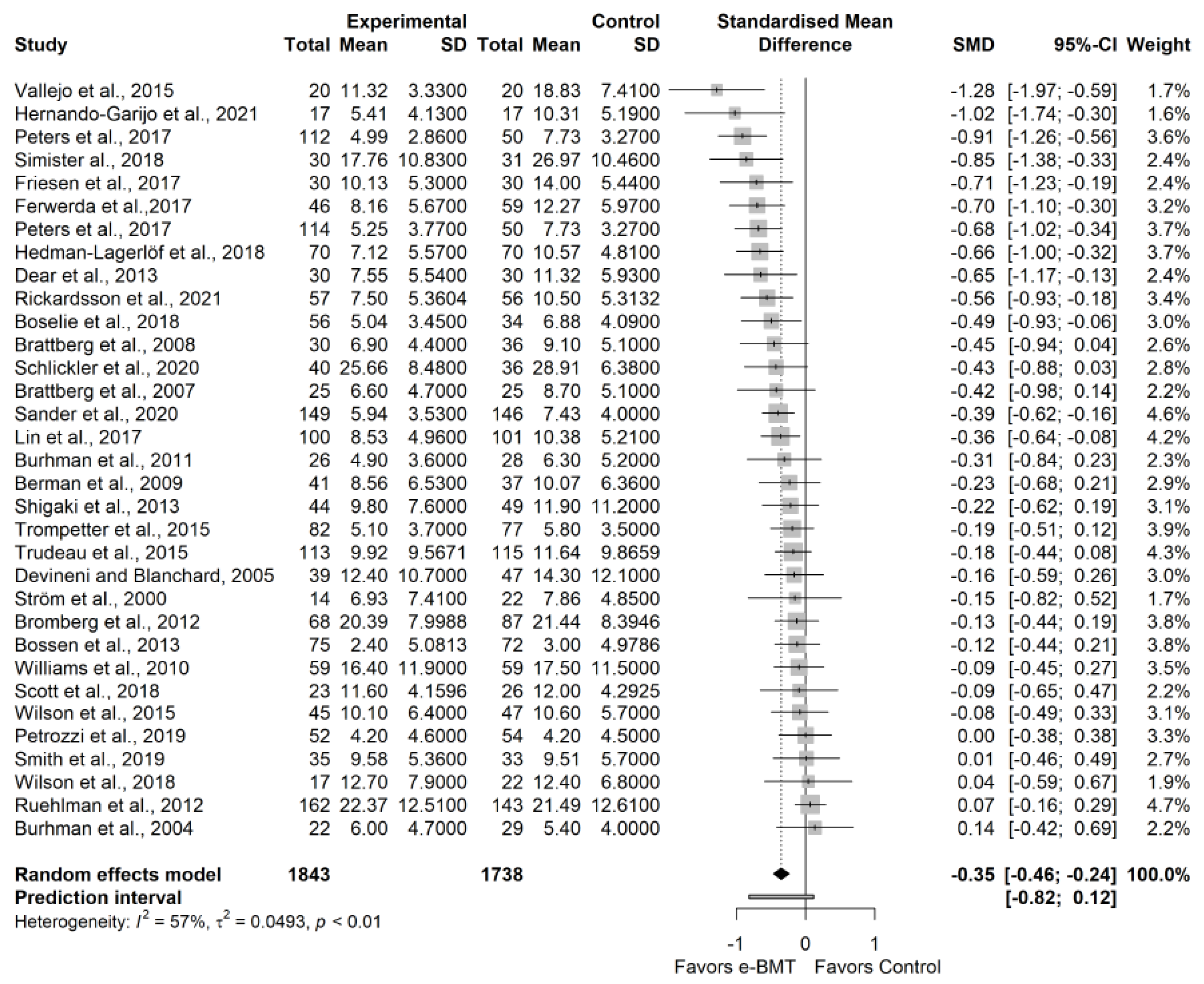

3. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

According to the PEDro scale, 30 were evaluated as having good [13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][27][28][30][31][34][35][36][37][38][40][42][43][44][45][47][48][49][50][52] and 11 as having fair methodological quality [24][25][26][29][32][33][39][41][46][51][53] (Appendix A.5). The inter-rater reliability of the methodological quality assessment between assessors was high (κ = 0.823). According to the Rob 2 scale, all the studies have a high risk of bias (100%) (Figure 1). The inter-rater reliability of the risk of bias assessment between assessors was high (κ = 0.884).

Figure 1. Risk of bias graph according to the Risk of Bias 2 tool.

Figure 1. Risk of bias graph according to the Risk of Bias 2 tool.

Figure 1. Risk of bias graph according to the Risk of Bias 2 tool.

Figure 1. Risk of bias graph according to the Risk of Bias 2 tool.4. Qualitative Synthesis

Four studies compared e-BMT with in-person BMT. They applied CBT [19][35], ACT [48] or person-centered intervention [22]. Two found non-statistically significant differences between groups for depressive symptoms (n = 253; MD = 0.24, 95% CI −2.32 to 2.80 [19] and MD = −0.51, 95% CI −2.42 to 1.40 [48]); however, Vallejo et al. found statistically significant between-group differences post-treatment in favor of e-BMT (n = 40; MD = −5.06, 95% CI −7.39 to −2.73) [35]. One found a non-statistically significant difference between groups for anxiety (n = 128; MD = −4.20, 95% CI −10.58 to 2.17) [48] and one found a non-statistically significant difference between groups for stress (n = 109; MD = −2.76, 95% CI −5.94 to 1.28) [22].

5. Quantitative Synthesis

5.1. Depressive Symptoms

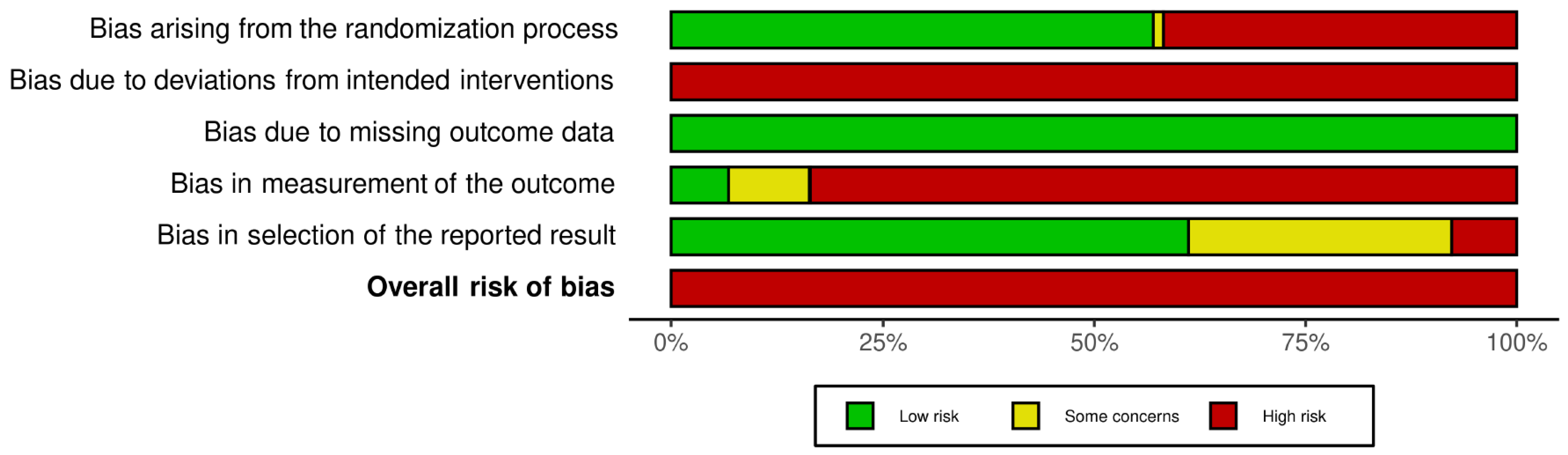

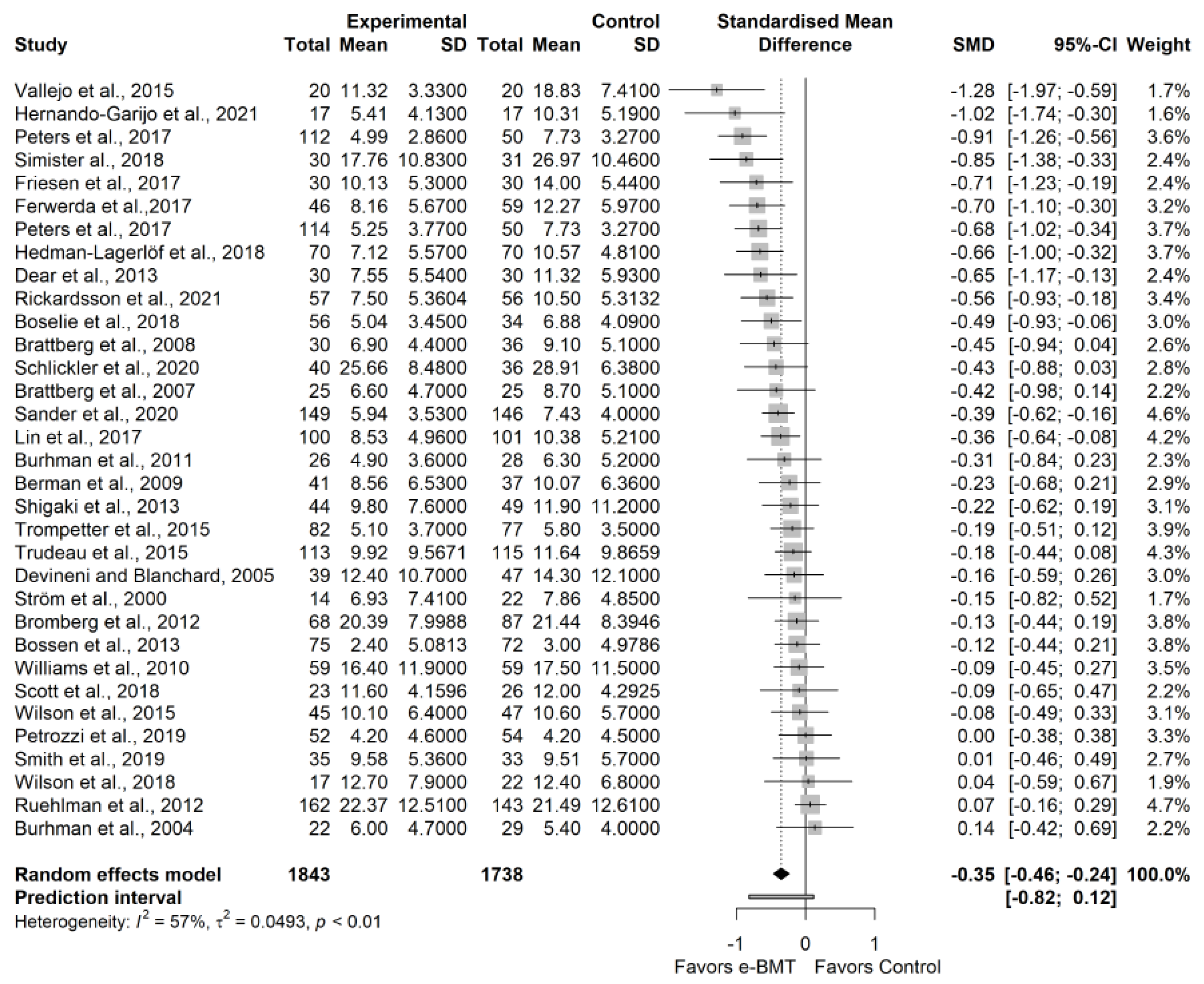

According to the influence analyses, researchers conducted a sensitivity analysis without Dear et al. [15]. Researchers found a statistically significant small effect size (32 RCTs; n = 3531; SMD = −0.35; 95% CI −0.46, −0.24) of e-BMT on depressive symptoms compared with usual care or waiting list, with significant heterogeneity (Q = 74.06 (p < 0.01); I2 = 57% (36%, 71%); PI −0.82, 0.12) and a low strength of evidence (Figure 2). Since PI crosses zero, researchers cannot be confident that future studies will not find contradictory results; however, the results appear to be robust to different p-value functions. With respect to the presence of publication bias, the funnel and Doi plots show an asymmetrical pattern, demonstrating minor asymmetry (LFK index = −1.62). When the sensitivity analysis is adjusted for publication bias, there is still a small significant effect. Subgroup analyses are detailed in Table 1a.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis of the depressive symptoms variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis of the depressive symptoms variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis of the depressive symptoms variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis of the depressive symptoms variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.Table 1. Subgroup analysis.

| Outcomes Sub = Analysis | N Studies | SMD | Lower Limit 95%CI | Upper Limit 95% CI |

Q | I2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Depressive Symptoms—Treatment | ||||||||||||||||

| ACT | 5 | −0.39 | −0.71 | −0.07 | 6.38 | 37% | ||||||||||

| RCT | Serious | CBT | 11 | −0.46 | −0.73 | −0.19 | 29.21 | 66% | ||||||||

| Positive Psychology | 2 | −0.61 | −1.77 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0% | ||||||||||

| Self-management | 8 | −0.12 | −0.26 | 0.03 | 6.30 | 0% | ||||||||||

| Other types of treatment | 7 | −0.30 | −0.58 | −0.03 | 11.19 | 46% | ||||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms—Chronic Musculoskeletal disorder | ||||||||||||||||

| Back pain | 5 | −0.24 | −0.53 | 0.05 | 5.58 | 28% | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | 7 | −0.66 | −1.01 | −0.31 | 14.16 | 58% | ||||||||||

| Headache | 3 | −0.14 | −0.19 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0% | ||||||||||

| Rheumatic disorders | 4 | −0.28 | −0.68 | 0.12 | 5.85 | 49% | ||||||||||

| Unspecified chronic pain | 13 | −0.33 | −0.51 | −0.15 | 36.61 | 65% | ||||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms—Added to usual care treatment? (Y/N) | ||||||||||||||||

| Only e-BMT | 24 | −0.34 | −0.46 | −0.22 | 52.26 | 54% | ||||||||||

| e-BMT added to usual care | 8 | −0.41 | −0.80 | −0.03 | 21.79 | 68% | ||||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms—Intervention duration | ||||||||||||||||

| Between 1 and 6 weeks | 6 | −0.02 | −0.17 | 0.12 | 2.44 | 0% | ||||||||||

| Between 7 and 11 weeks | 18 | −0.46 | −0.61 | −0.31 | 36.70 | 51% | ||||||||||

| 12 weeks and more | 8 | −0.26 | −0.50 | −0.03 | 12.54 | 44% | ||||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms—Methodological Quality according to the PEDro scale | ||||||||||||||||

| Fair methodological quality | 7 | −0.18 | −0.43 | 0.07 | 10.86 | 45% | ||||||||||

| Good methodological quality | 25 | −0.39 | −0.52 | −0.26 | 54.08 | 54% | ||||||||||

| (b) Anxiety—Treatment | ||||||||||||||||

| ACT | 3 | −0.31 | −0.93 | 0.31 | 4.75 | 58% | ||||||||||

| CBT | 10 | −0.31 | −0.50 | −0.12 | 14.71 | 39% | ||||||||||

| Positive psychology | 2 | −0.37 | -1.28 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0% | ||||||||||

| Self-Management | 3 | −0.20 | −0.70 | 0.30 | 2.34 | 15% | ||||||||||

| Other types of treatment | 4 | −0.41 | −0.97 | 0.14 | 8.43 | 64% | ||||||||||

| Anxiety—Chronic Musculoskeletal disorder | ||||||||||||||||

| Unspecific back pain | 3 | −0.09 | −0.75 | 0.58 | 2.43 | 18% | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | 5 | −0.45 | −0.85 | −0.05 | 8.17 | 51% | ||||||||||

| Headache | 1 | 0.18 | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||||

| Not Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious−0.14 | −0.85 | Rheumatic disorders | 2 | −0.35 | -2.47 | 1.77 | 1.67 | 40% | |||||

| Unspecified chronic pain | 10 | −0.33 | −0.47 | −0.19 | 16.12 | 38% | ||||||||||

| 1412 | 1166 | −0.32 | (−0.42; −0.21) | Moderate | ⊕⊕⊕ | Anxiety—Intervention duration | ||||||||||

| 1 to 6 weeks | 2 | 0.02 | -1.96 | 2.01 | 1.41 | 29% | ||||||||||

| 7 to 11 weeks | 13 | −0.41 | −0.50 | −0.31 | 10.34 | 0% | ||||||||||

| 12 weeks and more | ||||||||||||||||

| Stress (n = 4) |

RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | 399 | 390 | −0.13 (−0.28; 0.02) |

Moderate ⊕⊕⊕ |

6 | −0.25 | −0.56 | 0.06 | 9.13 | 45% |

| Anxiety—Added to usual care treatment? (Y/N) | ||||||||||||||||

| Only e-BMT | 17 | −0.34 | −0.45 | −0.22 | 26.85 | 37% | ||||||||||

| e-BMT added to usual care | 4 | −0.19 | −0.59 | 0.22 | 4.95 | 39% | ||||||||||

| Anxiety—Methodological Quality according to the PEDro scale | ||||||||||||||||

| Fair methodological quality | 5 | −0.18 | −0.40 | 0.04 | 6.61 | 24% | ||||||||||

| Good methodological quality | 16 | −0.37 | −0.49 | −0.24 | 22.28 | 33% | ||||||||||

Abbreviatures: ACT: Acceptance and Commitment therapy; CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI: Confidence interval; e-BMT: Telematic behavioral techniques; N/A: Not Applicable; SMD: Standardized mean difference; Y/N: Yes.

Abbreviatures: ACT: Acceptance and Commitment therapy; CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI: Confidence interval; e-BMT: Telematic behavioral techniques; N/A: Not Applicable; SMD: Standardized mean difference; Y/N: Yes.

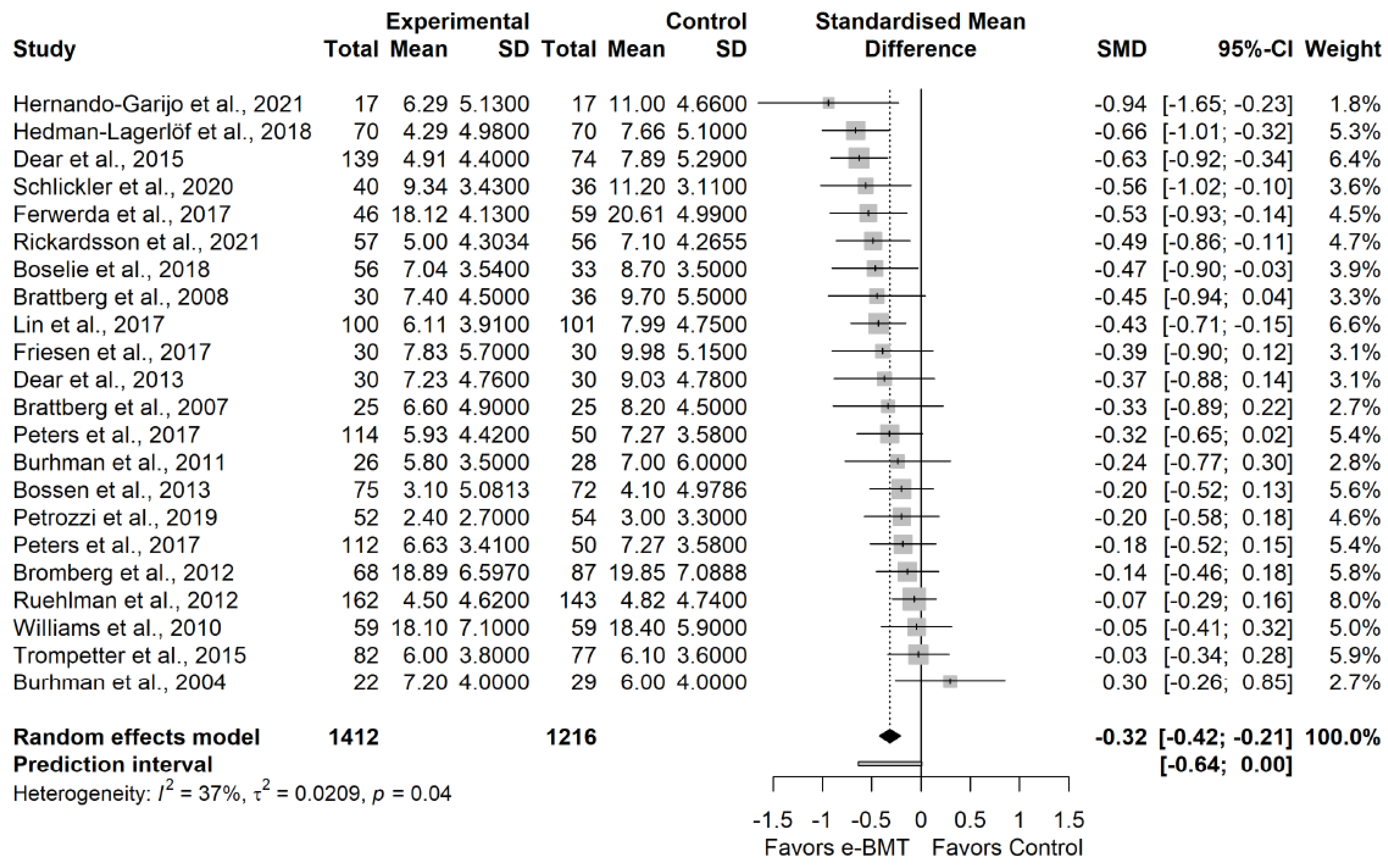

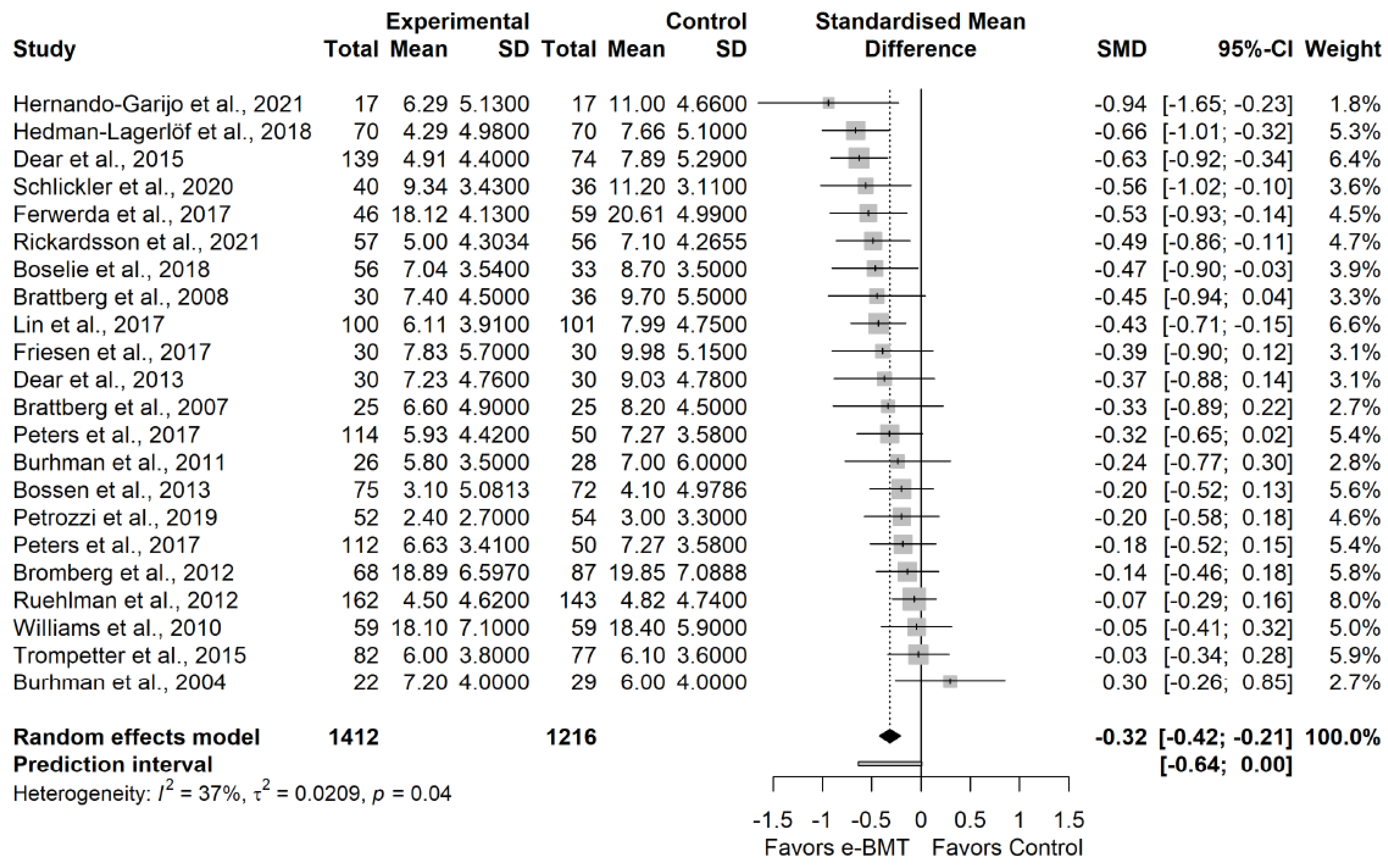

5.2. Anxiety

According to the influence analyses, researchers conducted a sensitivity analysis without Trudeau et al.

[34]

. Researchers found a statistically significant small effect size (21 RCTs; n = 2578; SMD = −0.32; 95% CI −0.42, −0.21) of e-BMT on anxiety compared with usual care or waiting list, with significant heterogeneity (Q = 33.47 (p

= 0.04); I2

= 37% (0%, 63%); PI −0.64, 0.00) and a moderate strength of evidence (Figure 3

). Since PI crosses zero, researchers cannot be confident that future studies will not find contradictory results; however, the results appear to be robust to differentp

-value functions. With respect to the presence of publication bias, the funnel and Doi plots show a symmetrical pattern, demonstrating no asymmetry (LFK index = −0.48). Subgroup analyses are detailed inTable 1b.

b.

Figure 3. Sensitivity analysis of the anxiety variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 3. Sensitivity analysis of the anxiety variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 3. Sensitivity analysis of the anxiety variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 3. Sensitivity analysis of the anxiety variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor the intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.5.3. Stress

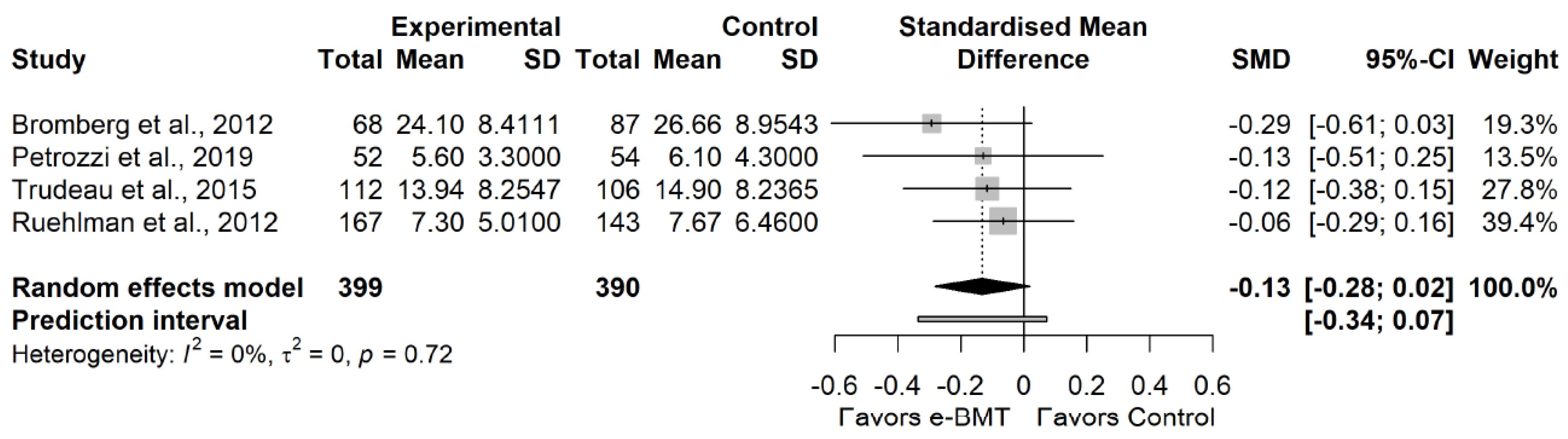

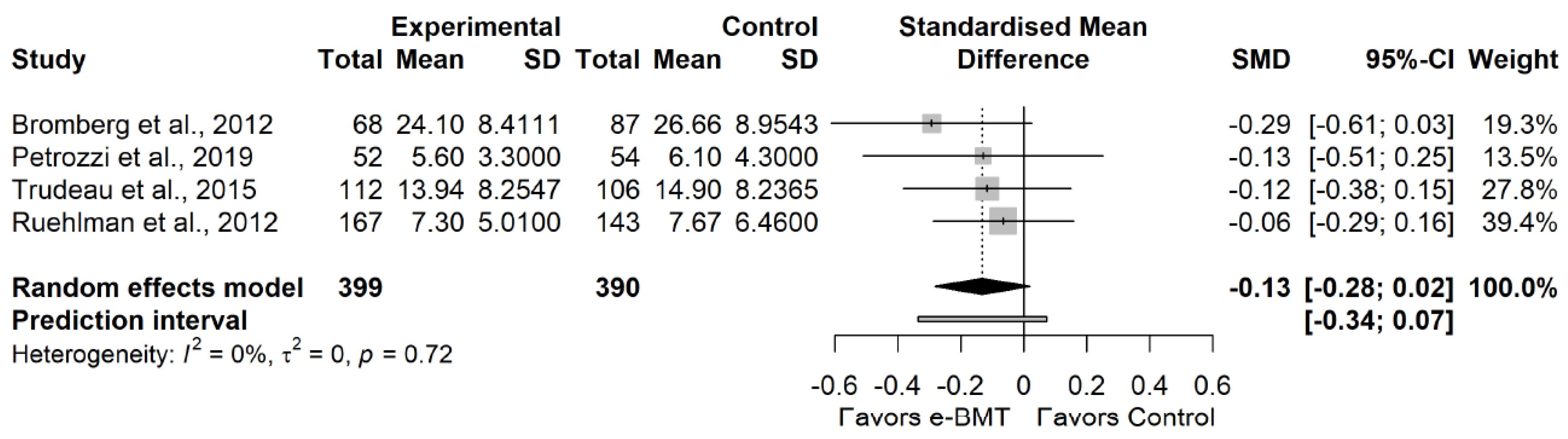

We found no statistically significant effect size (4 RCTs; n = 789; SMD = −0.13; 95% CI −0.28, 0.02) of e-BMT on stress compared with usual care or waiting list, with significant heterogeneity (Q = 1.33 (p = 0.72); I2 = 0% (0%, 85%); PI −0.34, 0.07) and a moderate strength of evidence (Figure 4). Since PI crosses zero, researchers cannot be confident that future studies will not find contradictory results. With respect to the presence of publication bias, the funnel and Doi plots show an asymmetrical pattern, demonstrating minor asymmetry (LFK index = −1.55). When the sensitivity analysis is adjusted for publication bias, there is no influence on the estimated effect.  Figure 4. Statistical analysis of the stress variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 4. Statistical analysis of the stress variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 4. Statistical analysis of the stress variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.

Figure 4. Statistical analysis of the stress variable for telematic behavioral modification techniques against usual care or waiting list. Negative results favor intervention group. The small boxes with the squares represent the point estimate of the effect size and sample size. The lines on either side of the box represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques.GRADE’s overall strength of the evidence is detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. GRADE’s overall strength of the evidence.

| Certainty Assessment | No. of Participants |

Effect | Certainty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome (No. of Studies) |

Study Design |

Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | e-BMT | Control | Absolute (95% CI) |

|

| Depressive symptoms (n = 32) | RCT | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | 1843 | 1688 | −0.35 (−0.46; −0.24) |

Low ⊕⊕ |

| Anxiety (n = 21) | ||||||||||

CI: Confidence interval, e-BMT: Telematic Behavioral Modification Techniques, RCT: Randomized controlled trial.

6. Discussion

The primary aim here with meta-analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness of e-BMT compared with usual care/waiting list or in-person BMT in terms of psychological variables. Secondly, researchers aimed to sub-analyze the results by intervention parameters and diagnostic conditions. The main results found that e-BMT seems to be an effective option for the management of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with musculoskeletal conditions causing chronic pain but not to improve stress symptoms. e-BMT does not seem to provide greater improvement than in-person BMT for psychological variables.

Several research studies have been published and have shown similar results to those found here with meta-analysis with regard to depressive and anxiety symptoms. For example, the rapid review conducted by Varker et al. [55] aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of e-BMT (by videoconference) and also through conventional mobile phone calls for people with high levels of anxiety and depression. The main results showed that both rehabilitation modalities produced significant positive results in terms of decreasing the levels of both psychological variables. In addition to this, the research conducted by McCall et al. [56] found that delivering psychological telematic interventions resulted in a significant decrease in depressive symptoms but could not be proven to be effective in comparison to face-to-face psychological intervention. Anxiety symptoms could not be assessed. This work included few studies, so the results have to be interpreted with caution.

In addition to being a possible alternative to in-person treatment, e-BMT appears to be a cost-effective technique compared to in-person BMT. De Boer et al. compared e-BMT and in-person BMT in patients with chronic pain and found that the costs of online CBT were EUR 199 lower than in-person BMT [57]. Similarly, Aspvall et al. found that after 6 months of follow-up in children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder, there was a difference of USD 1688 in favor of e-BMT [58]. Healthcare systems and guidelines should seriously consider implementing e-BMT in the management of patients with musculoskeletal disorders causing chronic pain.

References

- Clauw, D.J.; Häuser, W.; Cohen, S.P.; Fitzcharles, M.A. Considering the potential for an increase in chronic pain after the COVID-19 pandemic. Pain 2020, 161, 1694–1697.

- Eccleston, C.; Blyth, F.M.; Dear, B.F.; Fisher, E.A.; Keefe, F.J.; Lynch, M.E.; Palermo, T.M.; Reid, M.C.; Williams, A.C.d.C. Managing patients with chronic pain during the COVID-19 outbreak: Considerations for the rapid introduction of remotely supported (eHealth) pain management services. Pain 2020, 161, 889–893.

- Fallon, N.; Brown, C.; Twiddy, H.; Brian, E.; Frank, B.; Nurmikko, T.; Stancak, A. Adverse effects of COVID-19-related lockdown on pain, physical activity and psychological well-being in people with chronic pain. Br. J. Pain 2021, 15, 357–368.

- Pagé, M.G.; Lacasse, A.; Dassieu, L.; Hudspith, M.; Moor, G.; Sutton, K.; Thompson, J.M.; Dorais, M.; Montcalm, A.J.; Sourial, N.; et al. A cross-sectional study of pain status and psychological distress among individuals living with chronic pain: The chronic pain & COVID-19 pan-canadian study. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2021, 41, 141–152.

- Arteta, J.; Cobos, B.; Hu, Y.; Jordan, K.; Howard, K. Evaluation of how depression and anxiety mediate the relationship between pain catastrophizing and prescription opioid misuse in a chronic pain population. Pain Med. 2016, 17, 295–303.

- Curtin, K.B.; Norris, D. The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain. Scand. J. Pain 2017, 17, 156–166.

- Veehof, M.M.; Oskam, M.J.; Schreurs, K.M.G.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2011, 152, 533–542.

- Williams, A.C.d.C.; Fisher, E.; Hearn, L.; Eccleston, C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, CD007407.

- Du, S.; Hu, L.; Dong, J.; Xu, G.; Chen, X.; Jin, S.; Zhang, H.; Yin, H. Self-management program for chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 37–49.

- Ariza-Mateos, M.J.; Cabrera-Martos, I.; Prados-Román, E.; Granados-Santiago, M.; Rodríguez-Torres, J.; Carmen Valenza, M. A systematic review of internet-based interventions for women with chronic pain. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 84, 6–14.

- White, V.; Linardon, J.; Stone, J.E.; Holmes-Truscott, E.; Olive, L.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Hendrieckx, C.; Evans, S.; Speight, J. Online psychological interventions to reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and general distress in those with chronic health conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Med. 2020, 52, 1–26.

- Dario, A.B.; Moreti Cabral, A.; Almeida, L.; Ferreira, M.L.; Refshauge, K.; Simic, M.; Pappas, E.; Ferreira, P.H. Effectiveness of telehealth-based interventions in the management of non-specific low back pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Spine J. 2017, 17, 1342–1351.

- Amorim, A.B.; Pappas, E.; Simic, M.; Ferreira, M.L.; Jennings, M.; Tiedemann, A.; Carvalho-E-Silva, A.P.; Caputo, E.; Kongsted, A.; Ferreira, P.H. Integrating Mobile-health, health coaching, and physical activity to reduce the burden of chronic low back pain trial (IMPACT): A pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 1–14.

- Ang, D.C.; Chakr, R.; Mazzuca, S.; France, C.R.; Steiner, J.; Stump, T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy attenuates nociceptive responding in patients with fibromyalgia: A pilot study. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 618–623.

- Dear, B.F.; Gandy, M.; Karin, E.; Staples, L.G.; Johnston, L.; Fogliati, V.J.; Wootton, B.M.; Terides, M.D.; Kayrouz, R.; Perry, K.N.; et al. The Pain Course: A randomised controlled trial examining an internet-delivered pain management program when provided with different levels of clinician support. Pain 2015, 156, 1920–1935.

- Devineni, T.; Blanchard, E.B. A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based treatment for chronic headache. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005, 43, 277–292.

- Ferwerda, M.; Van Beugen, S.; Van Middendorp, H.; Spillekom-Van Koulil, S.; Donders, A.R.T.; Visser, H.; Taal, E.; Creemers, M.C.W.; Van Riel, P.C.L.M.; Evers, A.W.M. A tailored-guided internet-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis as an adjunct to standard rheumatological care: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2017, 158, 868–878.

- Friesen, L.N.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Schneider, L.H.; Alberts, N.M.; Titov, N.; Dear, B.F. Examination of an internet-delivered cognitive behavioural pain management course for adults with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Pain 2017, 158, 593–604.

- Heapy, A.A.; Higgins, D.M.; Goulet, J.L.; La Chappelle, K.M.; Driscoll, M.A.; Czlapinski, R.A.; Buta, E.; Piette, J.D.; Krein, S.L.; Kerns, R.D. Interactive voice response-based self-management for chronic back Pain: The Copes noninferiority randomized trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 765–773.

- Hedman-Lagerlöf, M.; Hedman-Lagerlöf, E.; Axelsson, E.; Ljotsson, B.; Engelbrektsson, J.; Hultkrantz, S.; Lundbäck, K.; Björkander, D.; Wicksell, R.K.; Flink, I.; et al. Internet-Delivered Exposure Therapy for Fibromyalgia A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. J. Pain 2018, 34, 532–542.

- Hernando-Garijo, I.; Ceballos-Laita, L.; Mingo-Gómez, M.T.; Medrano-De-la-fuente, R.; Estébanez-De-miguel, E.; Martínez-Pérez, M.N.; Jiménez-Del-barrio, S. Immediate effects of a telerehabilitation program based on aerobic exercise in women with fibromyalgia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2075.

- Juhlin, S.; Bergenheim, A.; Gjertsson, I.; Larsson, A.; Mannerkorpi, K. Physical activity with person-centred guidance supported by a digital platform for persons with chronic widespread pain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 53, jrm00175.

- Lin, J.; Paganini, S.; Sander, L.; Lüking, M.; Daniel Ebert, D.; Buhrman, M.; Andersson, G.; Baumeister, H. An Internet-based intervention for chronic pain—A three-arm randomized controlled study of the effectiveness of guided and unguided acceptance and commitment therapy. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 681–688.

- Moessner, M.; Schiltenwolf, M.; Neubauer, E. Internet-based aftercare for patients with back pain-A pilot study. Telemed. e-Health 2012, 18, 413–419.

- Berman, R.L.H.; Iris, M.A.; Bode, R.; Drengenberg, C. The Effectiveness of an Online Mind-Body Intervention for Older Adults with Chronic Pain. J. Pain 2009, 10, 68–79.

- Peters, M.L.; Smeets, E.; Feijge, M.; Van Breukelen, G.; Andersson, G.; Buhrman, M.; Linton, S.J. Happy Despite Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial of an 8-Week Internet-delivered Positive Psychology Intervention for Enhancing Well-being in Patients with Chronic Pain. Clin. J. Pain 2017, 33, 962–975.

- Petrozzi, M.J.; Leaver, A.; Ferreira, P.H.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Jones, M.K.; Mackey, M.G. Addition of MoodGYM to physical treatments for chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2019, 27, 1–12.

- Rickardsson, J.; Gentili, C.; Holmström, L.; Zetterqvist, V.; Andersson, E.; Persson, J.; Lekander, M.; Ljótsson, B.; Wicksell, R.K. Internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy as microlearning for chronic pain: A randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 1012–1030.

- Shigaki, C.L.; Smarr, K.L.; Siva, C.; Ge, B.; Musser, D.; Johnson, R. RAHelp: An online intervention for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 1573–1581.

- Simister, H.D.; Tkachuk, G.A.; Shay, B.L.; Vincent, N.; Pear, J.J.; Skrabek, R.Q. Randomized Controlled Trial of Online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Fibromyalgia. J. Pain 2018, 19, 741–753.

- Smith, J.; Faux, S.G.; Gardner, T.; Hobbs, M.J.; James, M.A.; Joubert, A.E.; Kladnitski, N.; Newby, J.M.; Schultz, R.; Shiner, C.T.; et al. Reboot Online: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing an Online Multidisciplinary Pain Management Program with Usual Care for Chronic Pain. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 2385–2396.

- Ström, L.; Pettersson, R.; Andersson, G. A controlled trial of self-help treatment of recurrent headache conducted via the Internet. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 722–727.

- Tavallaei, V.; Rezapour-Mirsaleh, Y.; Rezaiemaram, P.; Saadat, S.H. Mindfulness for female outpatients with chronic primary headaches: An internet-based bibliotherapy. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2018, 28, 175–184.

- Trudeau, K.J.; Pujol, L.A.; DasMahapatra, P.; Wall, R.; Black, R.A.; Zacharoff, K. A randomized controlled trial of an online self-management program for adults with arthritis pain. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 483–496.

- Vallejo, M.A.; Ortega, J.; Rivera, J.; Comeche, M.I.; Vallejo-Slocker, L. Internet versus face-to-face group cognitive-behavioral therapy for fibromyalgia: A randomized control trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 68, 106–113.

- Bossen, D.; Veenhof, C.; van Beek, K.E.; Spreeuwenberg, P.M.; Dekker, J.; de Bakker, D.H. Effectiveness of a web-based physical activity intervention in patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e257.

- Westenberg, R.F.; Zale, E.L.; Heinhuis, T.J.; Ozkan, S.; Nazzal, A.; Lee, S.G.; Chen, N.C.; Vranceanu, A.M. Does a brief mindfulness exercise improve outcomes in upper extremity patients? A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2018, 476, 790–798.

- Williams, D.A.; Kuper, D.; Segar, M.; Mohan, N.; Sheth, M.; Clauw, D.J. Internet-enhanced management of fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Pain 2010, 151, 694–702.

- Wilson, M.; Roll, J.M.; Corbett, C.; Barbosa-Leiker, C. Empowering Patients with Persistent Pain Using an Internet-based Self-Management Program. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2015, 16, 503–514.

- Wilson, M.; Finlay, M.; Orr, M.; Barbosa-Leiker, C.; Sherazi, N.; Roberts, M.L.A.; Layton, M.; Roll, J.M. Engagement in online pain self-management improves pain in adults on medication-assisted behavioral treatment for opioid use disorders. Addict. Behav. 2018, 86, 130–137.

- Ruehlman, L.S.; Karoly, P.; Enders, C. A randomized controlled evaluation of an online chronic pain self management program. Pain 2012, 153, 319–330.

- Sander, L.B.; Paganini, S.; Terhorst, Y.; Schlicker, S.; Lin, J.; Spanhel, K.; Buntrock, C.; Ebert, D.D.; Baumeister, H. Effectiveness of a Guided Web-Based Self-help Intervention to Prevent Depression in Patients with Persistent Back Pain: The PROD-BP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1001–1011.

- Trompetter, H.R.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Veehof, M.M.; Schreurs, K.M.G. Internet-based guided self-help intervention for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 66–80.

- Schlicker, S.; Baumeister, H.; Buntrock, C.; Sander, L.; Paganini, S.; Lin, J.; Berking, M.; Lehr, D.; Ebert, D.D. A web- and mobile-based intervention for comorbid, recurrent depression in patients with chronic back pain on sick leave (get.back): Pilot randomized controlled trial on feasibility, user satisfaction, and effectiveness. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e16398.

- Scott, W.; Chilcot, J.; Guildford, B.; Daly-Eichenhardt, A.; McCracken, L.M. Feasibility randomized-controlled trial of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for patients with complex chronic pain in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 1473–1484.

- Boselie, J.J.L.M.; Vancleef, L.M.G.; Peters, M.L. Filling the glass: Effects of a positive psychology intervention on executive task performance in chronic pain patients. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 1268–1280.

- Brattberg, G. Internet-based rehabilitation for individuals with chronic pain and burnout II: A long-term follow-up. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2007, 30, 231–234.

- Herbert, M.S.; Afari, N.; Liu, L.; Heppner, P.; Rutledge, T.; Williams, K.; Eraly, S.; VanBuskirk, K.; Nguyen, C.; Bondi, M.; et al. Telehealth Versus In-Person Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J. Pain 2017, 18, 200–211.

- Brattberg, G. Self-administered EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) in individuals with fibromyalgia: A randomized trial. Integr. Med. 2008, 7, 30–35.

- Bromberg, J.; Wood, M.E.; Black, R.A.; Surette, D.A.; Zacharoff, K.L.; Chiauzzi, E.J. A randomized trial of a web-based intervention to improve migraine self-management and coping. Headache 2012, 52, 244–261.

- Buhrman, M.; Fältenhag, S.; Ström, L.; Andersson, G. Controlled trial of Internet-based treatment with telephone support for chronic back pain. Pain 2004, 111, 368–377.

- Buhrman, M.; Nilsson-Ihrfelt, E.; Jannert, M.; Ström, L.; Andersson, G. Guided internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment for chronic back pain reduces pain catastrophizing: A randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 43, 500–505.

- Dear, B.F.; Titov, N.; Perry, K.N.; Johnston, L.; Wootton, B.M.; Terides, M.D.; Rapee, R.M.; Hudson, J.L. The Pain Course: A randomised controlled trial of a clinician-guided Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy program for managing chronic pain and emotional well-being. Pain 2013, 154, 942–950.

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95.

- Varker, T.; Brand, R.; Ward, J.; Terhaag, S.; Phelps, A. Efficacy of synchronous telepsychology interventions for people with anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and adjustment disorder: A rapid evidence assessment. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 621–635.

- McCall, T.; Bolton, C.S., III; Carlson, R.; Khairat, S. A systematic review of telehealth interventions for managing anxiety and depression in African American adults. mHealth 2021, 7, 31.

- De Boer, M.J.; Versteegen, G.J.; Vermeulen, K.M.; Sanderman, R.; Struys, M.M.R.F. A randomized controlled trial of an Internet-based cognitive-behavioural intervention for non-specific chronic pain: An effectiveness and cost-effectiveness study. Eur. J. Pain 2014, 18, 1440–1451.

- Aspvall, K.; Sampaio, F.; Lenhard, F.; Melin, K.; Norlin, L.; Serlachius, E.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Andersson, E. Cost-effectiveness of Internet-Delivered vs In-Person Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, 1–13.

More