c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) have emerged as suitable therapeutic strategies. In fact, it has been demonstrated that some unspecific JNK inhibitors exert antidiabetic and neuroprotective effects, albeit they usually show high toxicity or lack therapeutic value. In this sense, natural specific JNK inhibitors, such as Licochalcone A, are promising candidates. Nonetheless, research on the understanding of the role of each of the JNKs remains mandatory in order to progress on the identification of new selective JNK isoform inhibitors. In the present review, a summary on the current gathered data on the role of JNKs in pathology is presented, as well as a discussion on their potential role in pathologies like epilepsy and metabolic-cognitive injury. Moreover, data on the effects of synthetic small molecule inhibitors that modulate JNK-dependent pathways in the brain and peripheral tissues is reviewed.

- Epilepsy

- Metabolism

- Alzheimer's disease

- JNK

- Epilepsy, Metabolism, Alzheimer's disease, JNK

1. Introduction

In the present work, the relevance of the JNKs in the neuropathophysiology of two different diseases is reviewed: Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and metabolic-related late-onset non-familiar sporadic dementia.

2. Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a chronic, neurological disease that affects people of all ages and is characterized by a predisposition for the occurrence of recurrent seizures[1][2][3] [51–53]. Epidemiological data indicates that it contributes to 1% to 2% of the global burden of disease. In 2015, the CDC detected that 1.2% of the US had active epilepsy (about 3 million adults and 470,000 children[2][3][4] [52–54]. A seizure is a transient occurrence of a clinical manifestation of an abnormal, excessively synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Seizures may be focal when they originate within networks restricted to one cerebral hemisphere or generalized when they rapidly engage networks extended over both cerebral hemispheres[5] [5].

Temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common type of epilepsy in adults and is characterized by an affectation of the temporal lobe, especially the hippocampus and amygdala. It has been described that up to 30% of patients with TLE can develop a refractory epilepsy process[6] [55]. In addition, the existence of uncontrolled seizures ultimately leads to characteristic structural changes, such as hippocampal sclerosis. However, the molecular mechanisms leading to TLE are not fully elucidated.

Neuroanatomical examinations of patients with TLE have shown that they typically display sclerosis in the CA1, CA3, and hilus of the DG of the hippocampus, coupled with granule cell dispersion and sprouting of aberrant mossy fibers in the molecular layer of the DG[7] [56]. TLE also causes cognitive sequelae on memory, attention, language, praxis, executive function, judgment, insight, and problem solving[8][9] [57,58].

Current standardized treatments for epilepsy include a wide group of molecules with multiple mechanisms of action (antiepileptic drugs; AEDs), but, in about 30% of patients affected by this illness, the pathology becomes pharmacoresistant or refractory. It has been stipulated that this outcome is the consequence of a lack of understanding of all the mechanisms involved in the pathology, as well as due to the nature of AEDs that treat only the symptoms and not the underlying pathological mechanisms. In this situation, surgical resection of the affected tissue is the only alternative, but, in some occasions, it is impracticable or it only reduces the occurrence of seizures[2][7][10][11][12] [52,56,59–61].

On a molecular level, TLE is characterized by profound alterations in cellular homeostasis. As it has previously been mentioned, one of the consequences of seizure activity is the development of sclerotic tissue, derived from cellular death in neural tissue, coupled with inflammatory and immunological reactions[13][14] [62,63]. The appearance of gliosis, characterized by the proliferation and hypertrophy of glial cells, increases tissue damage and promotes the secretion of cytokines and chemokines (IL1, TNFα, IL6, IL10, interferon α and β, etc.). Crosstalk between neurons and glial cells in this situation reduces the seizure threshold in neurons[15] [64]. Moreover, seizures trigger the apoptotic extrinsic pathway, through the activation of response elements like the TNF receptor 1. Furthermore, the intrinsic pathway is activated as a result of high levels of calcium in the cytoplasmic compartment. This accumulation has negative consequences on a diverse array of organelles, including the mitochondria and ER, resulting in increased production and release of molecules like ROS and cytochrome c, and the upregulation of caspase activity.

The activation of IRE1α in the ER, as well as the release of ROS in the mitochondria, also favors the maintenance of a constant activated state of the JNKs[16][15][17][18] [19,64–66]. Indeed, Liu and colleagues[13] [62] demonstrated a significant increase in the IRE1-JNK response in the hippocampi of human patients suffering from TLE. In a rodent study evaluating miRNA expression patterns among different brain regions affected in TLE epileptogenesis, Gorter and colleagues found increased hippocampal miRNAs involved in the MAPK pathway and inflammation[19] [67]. They suggested that these miRNAs could be adequate target genes that would allow the development of a promising therapeutic strategy to prevent epileptogenesis. Moreover, they also evaluated the expression in the blood of miRNAs that could be useful as suitable potential biomarkers of the disease.

Activation of JNK was also observed in experimental models of temporal lobe seizures. Tai and colleagues found a significant JNK hyperactivation in rats treated with intraperitoneal administration of pilocarpine hydrochloride (385 mg/kg)[18] [66]. In another series of experiments, rats were treated with anisomycin, a nonspecific MAPK activator, which caused an increase in seizure frequency. To confirm the hypothesis that JNK overactivation could be relevant in chronic epilepsy, a wide-spectrum unspecific JNK inhibitor (SP600125) was administered and the same authors reported a significant reduction of the convulsive seizure frequency[18] [66]. Regarding this, it also has been reported that anisomycin mediates JNK activation through overexpression of JNK-interacting protein 3 (JIP3), a scaffold protein that is involved in the regulation of the apoptotic process[20] [68]. Interestingly, Wang and colleagues reported a selective neuronal localization of JIP3 in TLE patients and in rodents after post-seizure[21] [69]. Likewise, selective inhibition of JIP3 through the administration of a lentivirus (LV-375JIP3-RNAi) decreased seizure severity mediated by experimental convulsiveness[21] [69].

The use of preclinical models of TLE has allowed the roles of the different JNK isoforms in this disease to be described. Specifically, combining TLE preclinical models with isoform-specific JNK KOs has revealed that the absence of JNK1 and JNK3 renders neuroprotection in mice[22][23][24][25][26][27] [11,70–74]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the absence of these isoforms also reduces the occurrence and severity of seizures, glial reactivity, and the expression of proinflammatory genes[18][24] [66,71]. Finally, our research group has recently demonstrated that it also prevents the alteration of subpopulations of neurogenic cells after KA insults[25] [72].

3. The Metabolic-Cognitive Syndrome

Over the years, multiple studies have demonstrated a relationship between the appearance of cognitive deficits and phenomena like insulin resistance. This phenomenon causes impairments in glucose uptake both in central and peripheral regions. This alteration, which has a multifactorial origin, results in increased hepatic glucose production, favoring states of hyperglycemia and/or compensatory hyperinsulinemia in the periphery. Many pathologies like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver disease, impaired lung function, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease have been linked with this pathologic condition[26][27][28][29][30] [73–77].

Dr. Siegfried Hoyer was the first to mention this relationship. On his studies on the neuropathology of AD, he observed that a desensitization of the IRs might be a cause for the development of neurodegenerative hallmarks classically linked to dementia[31] [78]. Later, the Rotterdam study revealed an increased risk of dementia in diabetic patients, stablishing a clear relationship between hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia states and the development of pathologies like AD[32] [79]. Additionally, the analysis of human samples also yielded clear data demonstrating that AD patients show defective insulin signaling and response to this hormone just like altered levels and/or altered activation of components of the insulin signaling pathway[33] [80].

3.1. The Metabolism of Insulin

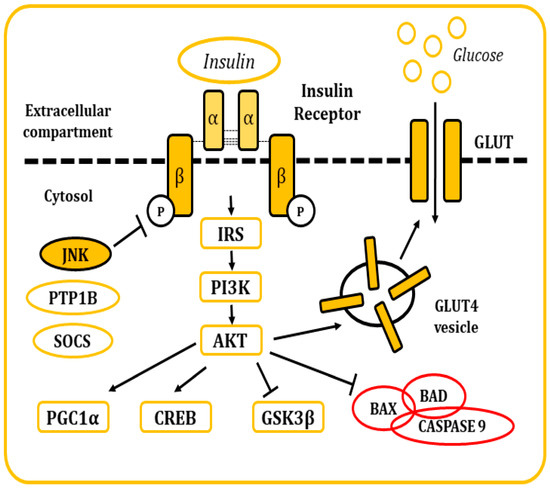

Insulin is a pancreatic polypeptide hormone produced by β cells in response to nutritional stimuli. It is responsible for the control of glucose concentrations in blood by stimulating their uptake into cells through its interaction with the IR[34][35] [81,82]. All tissues depend on this mechanism for the maintenance of their metabolism, specially muscle, adipose tissue, liver, and the brain. It also plays a role in the control of development, cell growth, and division among other physiological functions[34][35][36] [81–83]. The IR is a tetrameric tyrosine kinase protein made up of two extracellular α subunits and two transmembrane β subunits joined by disulphide bonds. On their resting state, α subunits behave as inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase activity of the β subunits. When insulin binds to the IR, this inhibition is relieved by the induction of conformational changes, allowing autophosphorylation of the IR in tyrosine residues[34][35][36][37] [81–84]. Thereon, insulin receptor substrate (IRS) molecules are recruited and, when activated through tyrosine phosphorylation, they are responsible for signal transduction within the cell of a whole myriad of signals that will regulate cellular physiology[34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41] [81–88] (Figure 15).

There are many regulatory mechanisms associated with the signaling of the IR that are involved in the maintenance of homeostasis. Yet, these mechanisms can also become dysregulated and be responsible for the development of pathological insulin resistance. In situations where insulin concentrations increase (hyperinsulinemia), the receptor becomes downregulated, internalized into vesicles, and, in some occasions, sent to lysosomal degradation[36] [83]. IR signaling can also be inhibited by inflammatory cytokines, which in turn will activate stimuli response elements like IKB kinase β or the JNKs, mainly JNK1. These kinases have been described to phosphorylate the IRS molecules in serine residues, leading to the development of a decrease in insulin sensitivity and metabolic dysfunction[35][42][43] [82,89,90]. Other elements responsible for the inhibitory control of insulin signaling include molecules like the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), responsible for the dephosphorylation of both IR and IRS proteins. Also, the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins reduce IR signaling by either occupying the phoshotyrosine activity site on the IR or by recruiting ubiquitin ligases that will induce proteasomal degradation of IRS[44][45] [91,92]. In the end, the dysregulation of these mechanisms is frequently associated with other conditions like obesity (visceral adiposity), systemic hypertension, hypercoagulation, and atherogenic dyslipidemia.

The occurrence of some or all of these alterations is referred to as metabolic syndrome. Worldwide, this condition is responsible for substantial morbidity and premature mortality[28] [75]. Specifically, overweight and obesity are major risk factors for the development of metabolic syndrome, acting, in many cases, as the source or the adjuvant of the rest of the mentioned alterations[46][47] [93,94].

Figure 15. Representation of the cellular response after insulin stimulation. Insulin binds to the IR and causes its activation. The posterior signaling cascade stimulates the uptake of glucose through the GLUT transporters. This signaling pathway is also responsible for the regulation of multiple cellular functions and response mechanisms.

3.2. The Metabolism of Insulin in the Brain

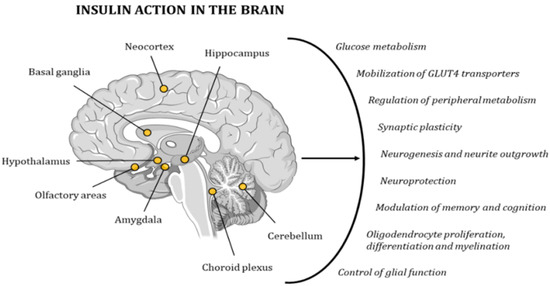

Due to its wide distribution of IRs, the brain is highly sensitive to insulin. The highest concentration of these receptors can be found in the hypothalamus, olfactory areas, limbic regions, neocortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, choroid plexus, and hippocampus[48][49][50][51] [95–98]. Insulin activity controls glucose metabolism and the mobilization of GLUT4 transporters in neurons and glial cells. In addition, it regulates multiple metabolic pathways in peripheral tissues through the regulation of hypothalamic activity. Furthermore, this hormone has neuroprotective effects and a role in memory and cognitive modulation, since it modifies synaptic plasticity, and regulates neurogenesis and neurite outgrowth. It also regulates oligodendrocyte proliferation, differentiation, and myelination, as well as glial function (Figure 26)[51][52] [98,99]. Hence, several studies have demonstrated the existence of a relationship between cognitive deficits and insulin resistance[31][32] [78,79]. In 2005, Dr. Suzanne M de la Monte coined the term type 3 diabetes (T3D) to define a state of brain insulin resistance plus insulin deficiency that, in some cases, can overlap with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)[53][54] [100,101]. In the last decade, many other researchers have backed up this hypothesis with other new discoveries and ground-breaking research projects[33][49][55][56][57] [80,96,102–104].

Figure 26. Insulin has a very strong effect on the functionality of the human brain, contributing to the maintenance of proper cognitive activity. The points in the image indicate the areas with the highest concentration in IRs.

3.3. Role of JNKs in Metabolic-Related Dementias

One of the most striking elements of this pathologic scenario is that there is a decrease in the number of IRs in the blood brain barrier. This reduces the transport of insulin into the brain and causes a decrease in insulin action[58] [105]. This situation favors mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS overproduction, as well as an increased activation of the UPR as part of the stress response[59][60][61][29][30][33][62] [9,29,43,76,77,80,106]. Furthermore, activation of astrocytes and microglia leads to chronic inflammation, causing tissue damage and degeneration through the release of cytokines like TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6, which later interact with receptors, such as the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)[63][33][49] [39,80,96].

This pathologic paradigm is usually aggravated in obesity, where the excessive accumulation of adipocytes in perivisceral areas and the waist promotes an increase in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and higher blood levels of other lipidic molecules, such as sphingolipids and ceramides, which have been associated with the development of insulin resistance[62] [106]. These dysregulations, and the subsequent cellular stress, increase the activation of stress-response elements like the JNKs. These molecules, in turn, phosphorylate IRSs in serine residues, feeding a vicious circle with further impairment of insulin signaling, as well as triggering the release, activation, and overproduction of pro-apoptotic molecules[64][65][61][29] [3,32,43,76]. Other consequences of this overactivation of JNKs include an alteration of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis and activation of PTP1B and SOCS3 molecules[61] [43]. In addition, obesity-induced JNK1 activation leads to ER stress and induction of the UPR pathway by a mechanism that requires the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR)[66][67] [107,108]. Likewise, obesity could activate JNK1 through saturated fatty acids that might act as ligands for TLR4.

In any case, eventually, dysregulations in metabolic activity have adverse effects on brain function and structure, inducing brain atrophy through the loss of grey matter, reduced integrity of white fiber tracts, white matter hyperintensity, infarcts, and microbleeds. Alterations can be either global or region specific, with a particularly detrimental effect in the medial temporal lobe, which includes the hippocampus. Other alterations include a loss of neurons, axodendritic pruning, reduced synaptic plasticity, and integrity, as well as decreased neurogenesis and cell proliferation, and a reduction in the number of dendritic spines. As a consequence of these events, impairments in learning, memory, and other cognitive functions may emerge[49][67] [96,108].