You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Conner Chen and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

Immunotherapies are emerging as promising strategies to cure cancer and extend patients’ survival. Efforts should be focused, however, on the development of preclinical tools better able to predict the therapeutic benefits in individual patients. In this context, the availability of reliable preclinical models capable of recapitulating the tumor milieu while overcoming the limitations of traditional systems is mandatory.

- cancer models

- immunology

- 3D biomaterials

1. Mechanisms Allowing Cancer Immune Evasion, a Lesson from 2D Cultures and Animal Models

Several efforts have been made in recent years to modify the human TME to overcome the limitations related to the species-specific gaps existing in animal models. However, modeling the TME, from an immune point of view, is still challenging due to the highly complex relationships between cancer cells and immune cells. A plethora of immune cells can interact with tumor cells and the TME, and, depending on the nature of these interactions, immune effectors can acquire either a tumor-suppressive or tumor-promoting function. In addition, immune cells do not act alone but interact with each other, orchestrating tumor immune responses [33,34][1][2].

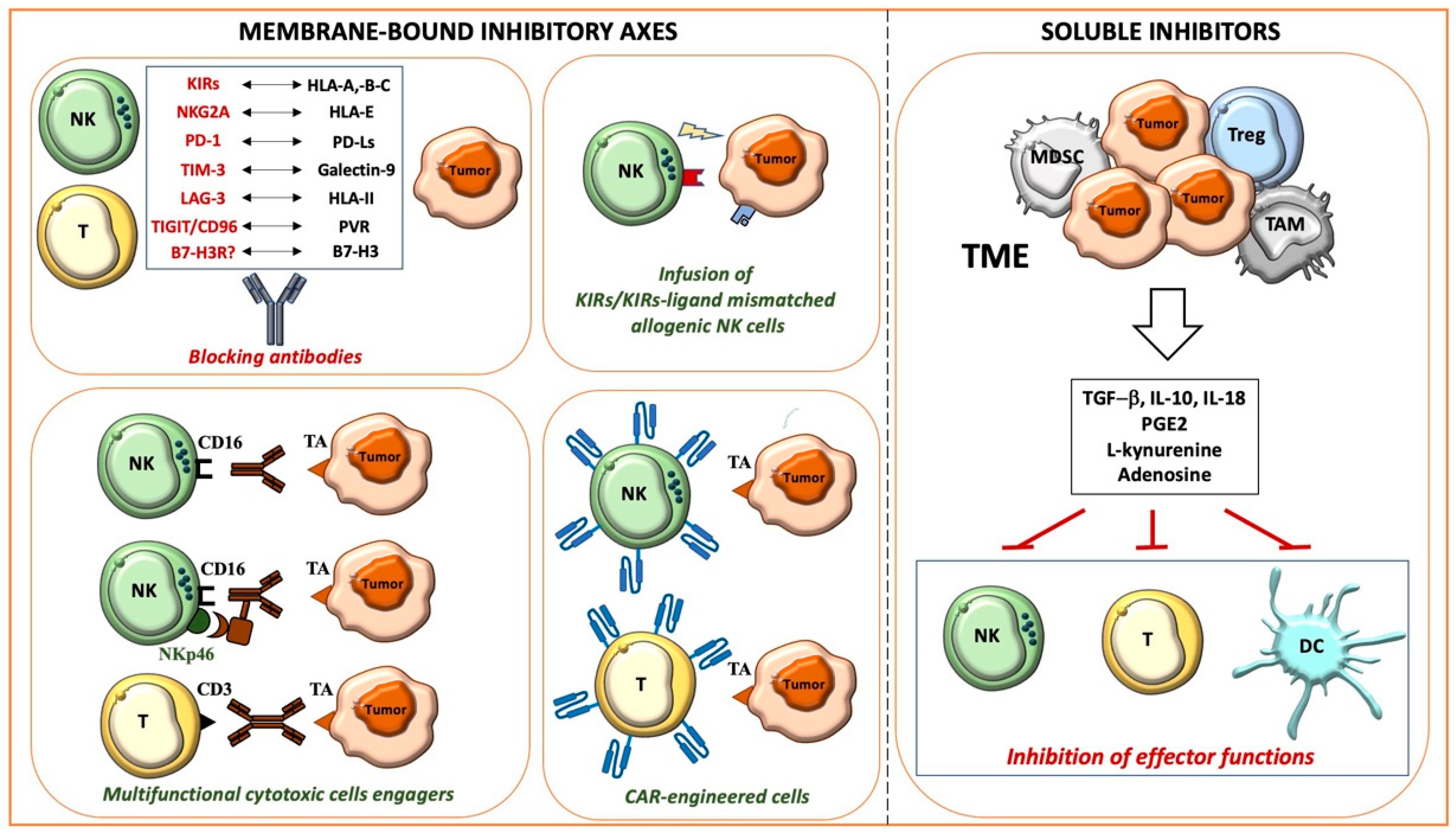

A huge amount of data indicates that a functional cancer immunosurveillance process exists. However, the relationship between cancer and immune cells is a complex dynamic process involving three phases, namely, Elimination, Equilibrium, and Escape, the so-called “3E’s of cancer immune-editing”. The Elimination phase is characterized by the successful activation of the immune system, leading to cancer cell recognition and death. In the Equilibrium phase, cancer cells adapt to the hostile environment established by the antitumor immune cells, enabling their survival and cohabitation. In the Escape phase, cancer cells, edited by the immune system, evade its aggression through mechanisms including the expression/upregulation of membrane-bound inhibitory axes, and the production of immunosuppressive soluble molecules [35][3]. The major tumor escape strategies are briefly described in the following paragraphs and illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Main mechanisms allowing cancer immune evasion and therapeutic strategies.

1.1. Membrane-Bound Inhibitory Axes and Therapeutic Approaches

1.1.1. HLA-I-Related Axes and Inhibitory Immune Checkpoints

Relevant membrane-bound inhibitory axes, negatively impacting the antitumor activity of innate and adaptive cytotoxic cells, are those involving HLA class I (HLA-I) molecules on target cells, and specific inhibitory receptors on effector cells, such as killer Ig-like receptors (KIRs), NKG2A, and LIR-1 [36][4]. These interactions have physiological functions: for example, licensing NK cells to acquire a suitable cytolytic potential [37,38][5][6] or tuning the activity of triggering receptors such as NKp46, NKp30, and NKp44 (collectively termed natural cytotoxicity receptors, NCRs), mainly expressed by NK cells, NKG2D, and DNAM-1, also characterizing a significant population of T cells [36,39][4][7]. HLA-Ihigh autologous healthy cells are generally protected from the NK cell-mediated aggression since the strength of the inhibitory signals prevails over that of the activating signals; the activating signals overcome the inhibitory signals in pathological conditions including tumors, where cell transformation leads to partial or complete HLA-I expression, together with the upregulation or de novo expression of ligands for activating receptors [36,39,40][4][7][8]. In some instances, however, tumors can preserve high levels of protective HLA-I, as occurs in hematological malignancies [41][9], or upregulate HLA-I as an adaptive mechanism to the IFN-γ and TNF-α mediators released by cytotoxic cells during tumor aggression [35,42][3][10].

To potentiate the cytotoxic antitumor responses, different strategies breaking the inhibitory receptor/HLA-I axes have been planned including those blocking KIRs [43][11] or NKG2A [44][12] with specific antibodies or hemopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplant with selected allogenic donors, generally the patient’s parents (haploidentical HSC, haplo-HSC) who can have NK cell populations with a KIR repertoire unable to recognize HLA-I alleles on the donors’ (KIR-KIR Ligand-mismatched NK cells). A further advance in the transplant setting is represented by TCR αβ/CD19-depleted haplo-HSC transplant, where cells infused in the recipient contain CD34+ HSC cells and mature immune cells including γδ T cells and NK cells, which provide early and effective antitumor and antiviral activities acting before the immune cell reconstitution from CD34+ cells [45][13].

The antitumor activity of cytotoxic cells can also be negatively regulated by several non-HLA-I-specific co-inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3, expressed by T and NK cells, interacting with ligands on tumor cells [46,47,48][14][15][16]. As with HLA-I, their ligands, PD-Ls (-L1 and -L2), HLA-II, and galectin-9, can be upregulated/induced by INF-γ released during the immune responses. Interestingly, an opposite regulation by INF-γ has been observed for PVR (poliovirus receptor, CD155) [23][17], a ligand shared by the inhibitory checkpoints TIGIT and CD96, and the activating DNAM-1 receptor.

The PD-1/PD-Ls and CTLA/CD28 axes, whose discovery was awarded with the 2018 Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology, represent the prototypic immune checkpoints firstly targeted in cancer patients. In particular, the blockade of the PD-1/PD-Ls axis has revolutionized the treatment of many metastatic advanced tumors either as monotherapy or in combination with other therapeutic strategies. Several clinical trials combine PD-1/PD-Ls blockade with the infusion of antibodies specific for Tas, which unleash cytotoxicity and IFN-γ release by NK and T cells, promote phagocytosis, and complement activation. The use of antibodies as bullets reaching the right target, sparing normal cells, represents a strategy commonly used in tumors characterized by a high expression of the selected antigen that, conversely, shows a limited/low expression in normal tissues. These antibodies are often engineered to be more effective, for example, by mutating their Fc portion to reduce their binding with inhibitory or low-affinity FcγRs, or conjugating them with toxic drugs [49][18]. Recently, to further improve the cytotoxicity of NK cells, a strategy has been developed based on multifunctional engagers simultaneously targeting Tas and CD16 (FcγRIIIA) and NKp46 activating receptors in NK cells [50][19].

Additional tools to efficiently and specifically target both hematological malignancies and solid tumors are represented by T cells engineered with chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) specific for Tas, which have been optimized in recent years with the construction of more effective third-generation CARs, which also express an inducible suicide gene to induce, in case of adverse side effects, the rapid in vivo depletion of CAR-T. CARs deliver a cell activation signal that, in most instances, is strong enough to overcome the inhibitory axes. Recently, there has been an increasing interest in the generation of CAR-engineered NK cells, effectors that appear to be superior in terms of safety and that naturally express different receptors against tumor-associated molecules [51,52][20][21].

1.1.2. Novel Inhibitory Immune Checkpoints: B7-H3 and CD47

One of the most promising recently discovered tumor targets is B7-H3 (CD276) [53[22][23][24],54,55], highly expressed by several tumors and upregulated by IFN-γ [23][17]. Importantly, B7-H3 also shows a higher expression on the tumor-associated vasculature compared to normal vessels, whereas it is not expressed at significant levels on most normal tissues. B7-H3 represents an additional ligand of the growing list of immune checkpoint axes, physiologic mechanisms controlling the duration and the resolution of the immune responses [53,56,57,58][22][25][26][27]. Unfortunately, these inhibitory axes are “adopted” by tumors to escape immune surveillance. B7-H3 acts on two sides, inhibiting the T and NK cell-mediated antitumor activity by reacting with a still unknown receptor, and favoring tumor progression by promoting migration, invasiveness, and drug resistance [52,59,60][21][28][29]. For these reasons, B7-H3 represents a consolidated negative prognostic marker in several adult and pediatric tumors including neuroblastoma (NB) [61][30]. In particular, in primary NB, high B7-H3 surface expression also correlates with poor survival in patients with localized disease, indicating that the analysis of its expression could improve patients’ risk stratification [60,61][29][30].

Different therapeutic strategies targeting B7-H3 have been explored in preclinical studies with promising results [49,62,63,64,65,66][18][31][32][33][34][35]. Phase I clinical trials based on the infusion of humanized anti-B7-H3 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been completed in adult and pediatric tumors including NB (NCT02982941), with results supporting the design of phase II and III clinical trials.

Whereas all the previously described molecules mainly impair lymphocyte-mediated immune surveillance, CD47 and its ligands, thrombospondin-1 and signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα), represent an inhibitory axis limiting phagocyte activity. Different from B7-H3, which can be considered a tumor-associated antigen, CD47 is overexpressed by many types of tumors but is also widely expressed in normal cells. The interaction of CD47 with SIRPα gives macrophages a “don’t eat me” signal, inhibiting phagocytosis and allowing tumor cells to evade immune surveillance. The CD47/SIRPα axis is emerging as a key immune checkpoint in different cancers including hematological malignancies. This drives the development of immunotherapeutic strategies aimed to disrupt this brake. Importantly, however, due to the broad expression of CD47 on healthy cells, deep preclinical and clinical studies proving the safety of this therapeutic approach are required.

1.2. Soluble Mediators and Therapeutic Approaches

1.2.1. TGF-β and IL-10

Several soluble mediators are establishing an immunosuppressive milieu within the TME. Cytokines, growth factors, and metabolites, eventually packed into extracellular vesicles such as exosomes, play a central role in the intricate networking between cancer and immune cells, as well as between the different immune cell subsets.

Suppressive cytokines are either produced by tumor cells or immune cells having an immunosuppressive/pro-tumoral activity such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and type 2 polarized tumor-associated neutrophils (N2, TANs) or macrophages (M2, TAMs). TAMs heavily contribute to tumor progression, exerting a suppressive and opposite role as compared to their proinflammatory M1 counterpart [67][36]. Among the cytokines involved in the generation of a suppressive microenvironment, TGF-β and IL-10 are known to play a central role. TGF-β has a direct pro-tumor effect on cancer cells and promotes the exhaustion of immune responses in different types of cancer [68][37]. In particular, TGF-β suppresses NK cells through multiple mechanisms. These include the direct inhibition of the mTOR pathway, impairing NK cell activation and function [69[38][39],70], the downregulation of the expression of different activating receptors including NKp30, NKG2D [71][40], DNAM-1, and CD16 [72[41][42],73], and the modulation of ligands on target cells [74,75][43][44]. TGF-β also modifies the chemokine receptor repertoire of NK cells, likely impacting their recruitment at the tumor site [76[45][46],77], and promotes the generation of NK cells with a low cytotoxic ILC1-like phenotype [78][47]. Interestingly, unlike other typical immunostimulatory cytokines such as IL2, IL-12, and IL-15, IL-18 potentiates rather than suppresses some of the TGF-β-mediated modulatory effects [79][48]. Besides the classical soluble form, recent findings show that the antitumor function of NK cells can also be suppressed via the contact with membrane-bound TGF-β expressed on metastasis-associated macrophages or Tregs [80,81][49][50].

Regarding the regulatory properties of TGF-β on T cells, the cytokine has been demonstrated to inhibit the differentiation of T cells toward the antitumor Th1 phenotype, inhibit their proliferation through IL-2 downregulation, and impair the cytotoxic effect of CD8+ T cells through the repression of granzyme B and IFN-γ. Moreover, TGF-β is involved in the upregulation of FoxP3 in CD4+ naïve T cells, inducing their differentiation toward Tregs [82,83[51][52][53][54],84,85], and, accordingly, TGF-β blockade results in Treg depletion in different cancers [86,87][55][56]. Importantly, TGF-β has also been correlated with resistance to the immune checkpoint blockade, as demonstrated by Hugo et al. through transcriptomic analysis on metastatic melanoma specimens [88][57]. Thus, TGF-β blockade can also be considered as a strategy to enhance the efficacy of therapies including the inhibition of immune checkpoints [89,90][58][59] and the adoptive transfer of CAR-engineered T cells [91,92][60][61]. An attractive approach is the combined targeting of immune checkpoint molecules and TGF-β within the same moiety, which has been demonstrated to be more effective in vivo than the single targeting [93][62]. Along this line, in a recent paper, Chen et al. engineered CAR-T cells secreting a bispecific trap protein binding PD-1 and TGF-β, demonstrating a significant improvement in effector T cell engagement, persistence, and expansion, preserving CAR-T cells from exhaustion, and leading to high antitumor efficacy and long-term remission in animal models [94][63].

IL-10 is a cytokine, mainly produced by Tregs, B cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages, suppressing the function of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and CD4+ T cells [95][64]. The immunosuppressive role of IL-10 has been attributed to the downregulation of IFN-γ, the impairment of DC maturation, and the downregulation of HLA-I, on cancer cells, and HLA-II and costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86), on APCs [96,97,98][65][66][67]. Moreover, Ma et al. recently demonstrated that the over-production of IL-10 converts lymphoma-associated Th1 cells into FoxP3-negative/PD-1-overexpressing T regulatory type 1 cells, generating an immune escape signature [99][68]. IL-10 can also induce a pro-tumor phenotype in macrophages during the early phases of tumor formation, as demonstrated by Michielon et al. in 3D organotypic melanoma cultures [100][69]. Similar to TGF-β, IL-10 expression could be considered as a predictive biomarker of response to the blockade of immune checkpoints, especially when considering the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio.

1.2.2. PGE2 and Metabolites

Specific classes of prostaglandins (PGs), molecules involved in inflammatory processes, have been associated with cancer development and progression. Namely, PGE2 contributes to the immunosuppressive tumor milieu. For example, produced by melanoma-associated fibroblasts, PGE2 negatively regulates the expression of NKp44 and NKp30 activating receptors in NK cells [101][70]. In breast cancer, it has been found to be associated with reduced CD80 expression on macrophages, thus hindering the antitumor immune response, and the administration of ibuprofen in vivo led to tumor shrinkage, active recruitment of T cells, and the reduction in immature monocytes [102,103][71][72]. Recently, the COX2/PGE2 pathway has been associated with M2 polarization of macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma patients, and M2 macrophages were found to inhibit the production of IFN-γ and granzyme B from CD8+ T cells both in vitro and in vivo [104][73]. Therefore, the administration of PGE2-inhibiting drugs might help in the re-education of the TME. Studies performed on syngeneic mouse models revealed that the combinatory administration of a PGE2 receptor antagonist and PD1 blockade had a synergistic effect, leading to a massive reorganization of the tumor immune environment [105][74].

Studies in skin squamous cell carcinoma reported that PGE2 is associated with increased tumor cell migration and invasion, correlating with the staging [106][75]. This correlation has also been reported in gliomas, where PGE2 seems to be involved in the promotion of the tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase pathway, known to mediate tolerogenic signaling through multiple mechanisms [107,108][76][77].

The accumulation of kynurenine due to tryptophan catabolism leads to its binding to AhR, further exerting an immunosuppressive pressure. The AhR nuclear translocation results in the upregulation of FoxP3 and IL-10 in T cells, driving the acquisition of a regulatory phenotype, reducing the immunogenic capacity of DCs [109[78][79][80][81],110,111,112], and upregulating PD-1 expression on effector T cells [113][82]. Importantly, the inhibitory effect of kynurenine has also been well documented in human NK cells [114][83]. In particular, l-kynurenine hampers the cytokine-mediated strengthening of the NK-cell-mediated killing, limiting the upregulation of NKp46 and NKG2D receptors. As a consequence, NK cells conditioned by l-kynurenine display a reduced ability to kill target cells mainly recognized via these receptors. Given all these observations, it is not surprising that different therapeutic approaches targeting the Trp-Kyn-AhR pathway are currently in preclinical development or clinical trials, in combination with standard therapies [115][84].

Another important metabolite exerting an immunosuppressive effect is adenosine, which can be generated within the TME due to the over-secretion by tumor cells of ATP and its catabolism by specific ectoenzymes. Intracellular ATP, produced by glycolytic or oxidative metabolism, can be released in the extracellular space through passive efflux or active secretion [116][85]. A “passive” release, due to a high intracellular concentration, can be associated with cytotoxicity, meaning that ATP represents a cell damage marker. The active secretion occurs through exocytosis or membrane transporters such as the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) proteins and is triggered by events such as hypoxia [117][86]. Importantly, hypoxia also induces the overexpression of CD39 and CD73 ectoenzymes, promoting the conversion of ATP to AMP and AMP to adenosine, respectively, as well as the downregulation of adenosine kinase, limiting the conversion of adenosine in its final metabolites and leading to the accumulation of adenosine in the extracellular space [118][87]. The ectonucleotidases can be expressed by tumor cells and different subsets of innate or adaptive immune cells [116,119,120][85][88][89]. Moreover, it has been reported that tumor cells and tumor-derived exosomes can carry CD39 and CD73 on their membranes, thus promoting ATP conversion and adenosine accumulation in the TME [120,121][89][90].

Adenosine also promotes the conversion of macrophages toward the immunosuppressive M2 phenotype, and the release of MMPs by tumor-associated neutrophils, thus favoring the invasive and metastatic process [122,123,124,125][91][92][93][94]. In Tregs, the activation of A2A receptors induces the proliferation, activation, and overexpression of the CTLA-4 and PD-1 immune checkpoints [126][95].

2. Three-Dimensional Culture Models: Moving from Spheroids to Next-Generation 3D Tools

Despite the significant information described in the previous sections and obtained by using 2D cultures and animal models, few tumor escape mechanisms have been addressed in 3D platforms, pointing out the need to move quickly towards these more reliable 3D culture systems.

These systems represent next-generation 3D tools that are slowly replacing spheroid-based strategies widely employed thus far to investigate tumor-immune system interactions in vitro and that still represent one of the gold standard 3D models to assess tumor–immune cell interactions. In particular, these tools could gain insights into T and NK cell-related infiltration, cytotoxicity, and soluble factor release [131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107]. Moreover, spheroids have allowed deepening the understanding of the effects of the TME on macrophages’ polarization and functions [139,140,141][108][109][110].

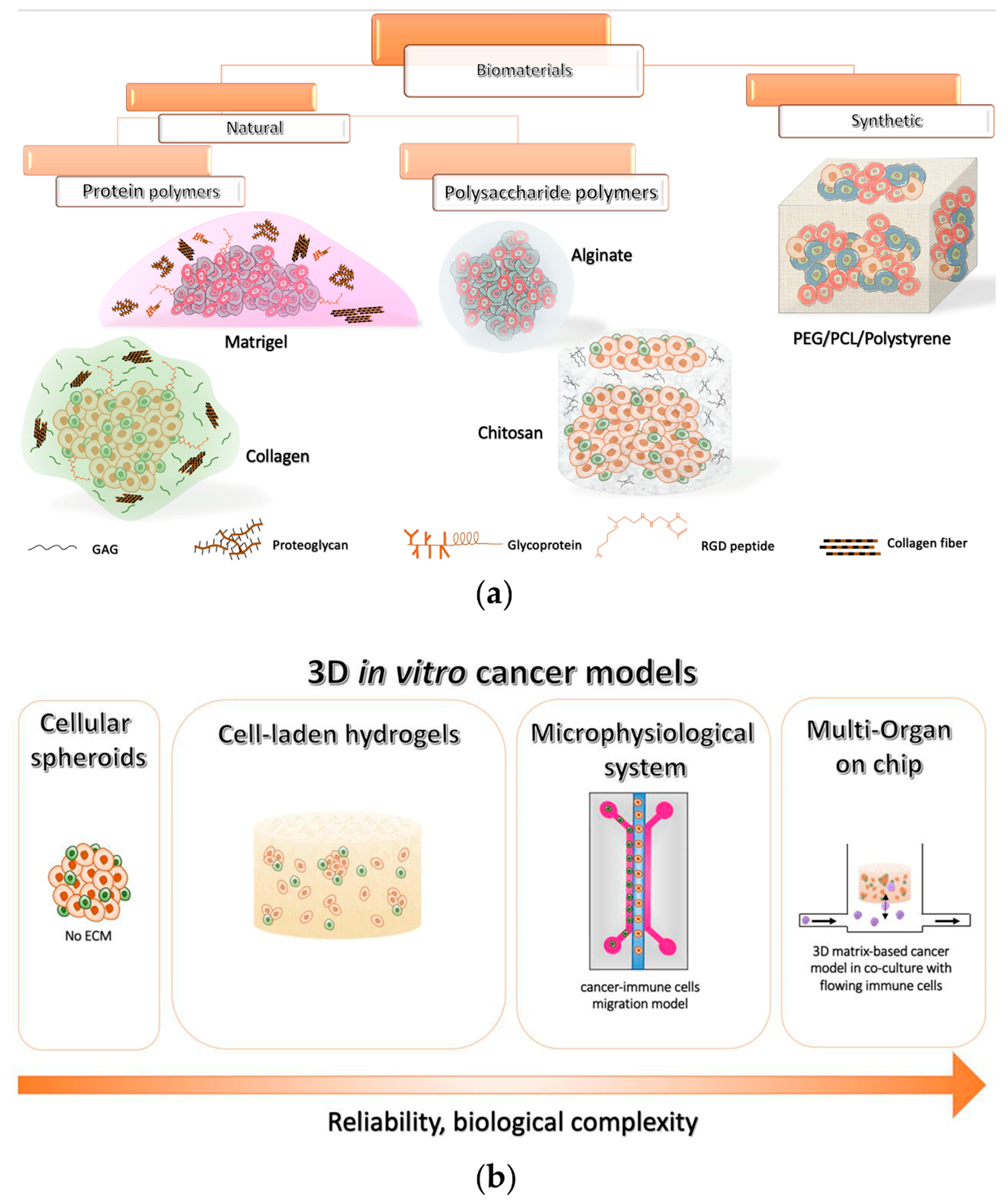

Despite these encouraging outcomes, the absence of an ECM limited the reliability of such spheroid-based systems and hampered the evaluation of the effects of chemical–physical properties of the surrounding microenvironment on cell activity [142,143][111][112]. Therefore, many researchers and material scientists are moving towards scaffold-based 3D platforms, which can also be integrated with different components of the TME. In thHe following sections, here will recapitulate the state of the art of 3D hydrogel-based in vitro models that have been adopted to studyexplore tumor and immune system interactions as well as novel immunotherapeutic approaches (summarized in Table 1), describing the different types of biomaterials that have been employed (schematically reported in Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Overview of the current 3D in vitro cancer models (a) Classification of the most used polymeric biomaterials for 3D models and their schematic representation. (b) Evolution of 3D in vitro models for investigating cancer immunotherapies.

2.1. Natural Biomaterial Tools for 3D Tumor Modeling In Vitro

Biomaterials of natural origin are the most employed materials in several biomedical applications, due to their high biocompatibility, bioactivity, mechanical and biochemical properties similar to those of the ECM in vivo, and the presence of chemical cues promoting cell attachment and proliferation, reciprocal communication, and tumorigenesis, thus being a gold standard in cancer research [144,145][113][114]. They can be assigned to two main categories: (i) protein polymers, and (ii) polysaccharide polymers.

2.1.1. Protein-Based Polymers

Among biomaterials for 3D tumor modeling in vitro, the most adopted is Matrigel, which is an extract of the basement membrane matrix of Engelbreth Holm Swarm mouse sarcoma. This commercially available ECM, which generates a hydrogel at 24–37 °C, has a very similar content to the in vivo counterpart as it comprises various ECM macromolecules such as collagen IV, fibronectin, laminin, and proteoglycans, as well as different growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, and proteases [146,147][115][116]. Due to these constituents, Matrigel represents a biologically active platform able to promote the adhesion, migration, and differentiation of different cell types in vitro. Therefore, being easily available and versatile, and applicable with a wide variety of cellular phenotypes, it represents a standard support matrix for cell culture in several biomedical applications. In particular, it has been largely employed in 3D tumor modeling for the investigation of cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and drug efficacy [146][115]. Tumor cells are extremely proliferative in Matrigel-assisted cultures, differently from normal cells, showing an in vivo-like invasive profile. It has also been proved that 3D Matrigel matrices allow cells to express fundamental features related to their intrinsic malignancy [143][112]. For example, in the case of breast cancer, it is possible to discern poorly or highly aggressive cells when they are encapsulated within this hydrogel by examining their morphology. They usually organize into small aggregates (i.e., acini-like structures, luminal phenotype) or display an elongated shape with pronounced extensions (basal phenotype). Malignant cells are also capable of migrating through Matrigel matrices by enzymatic degradation, which is commonly studied through the Boyden chamber assay [143][112].

It is widely recognized that the cancer invasive profile also correlates with the ability of tumor cells to evade the immune surveillance as well as driving different types of immune cells to participate in cancer progression through cell–cell contacts and release of soluble factors [148,149][117][118]. For example, Ramirez et al. demonstrated that malignant cancer cells are capable of inducing macrophages to change the gene expression profile. Indeed, in a 3D Matrigel-based system, the interplay between the human macrophage U937 cell line and breast tumor cells caused, in U937, a significant upregulation of MMP1 and MMP9, both involved in tumor invasion via ECM degradation. Moreover, an upregulation of the inflammatory COX2 gene inducing the pro-tumoral factor PGE2 was observed. Such increments were significantly higher in the co-cultures of U937 with MDA-MB-231 cells, a highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer cell line, than with MCF7, which has characteristics of a differentiated mammary epithelium [150][119]. The same group, in a later work, showed that primary breast cancer cells constitutively secrete high levels of CCL5, CCL2, and G-CSF, specifically involved in the attraction of circulating immune cells at the tumor site, while a remarkable increase in IL-1β, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-10 production was revealed when cancer cells were co-cultured with monocytes [151][120].

Taken together, these data support the idea that tumor aggressiveness is related to its capability to shape the inflammatory microenvironment by recruiting immune cell populations at the tumor site and instructing them to fulfill pro-tumoral functions. Therefore, it is evident that the interactions occurring within the TME between different cell types, including stromal cells, play a fundamental role in promoting disease progression [152,153][121][122].

Hence, tissues explanted during surgical resections or biopsies have been embedded in Matrigel to investigate immune cell populations infiltrating the tumors [154,155][123][124]. For instance, in slices derived from tissues of patients with colorectal and lung cancer, a great presence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (CD206+/CD33+/HLA-DR–-) and CD4-/CD8-T cells, as well as a reduced number of NK cells and monocytes, has been observed [156][125]. Moreover, innovative organotypic cultures have been adopted by co-culturing organoids established from patient-derived cancer cells (due to their capability of retaining key pathophysiological and structural features of the original tumor in vitro [157][126]), with patient-matched stromal (e.g., CAFs) and immune components (e.g., T cells) [158][127]. These systems represent a valuable tool for studying the complex tumor–stroma–immune system communications in a highly reliable context, paving the way for the assessment of novel personalized immunotherapeutic strategies. To this end, more recently, Dijkstra et al. co-cultured autologous colorectal or non-small lung cancer tumor organoids with peripheral blood lymphocytes, with the intention of increasing the number of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells to be infused in patients [154][123]. Furthermore, other groups focused on testing novel engineered immune cell-mediated strategies. Among them, αβT cells modified to express a tumor-specific γδ TCR (TEGs) were used in primary myeloma cells grown within a 3D BM niche model [159][128]. Moreover, the CAR-NK-92 cell line was proposed as an effector against patient-derived colorectal cancer organoids by targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) [160][129], overexpressed in a wide variety of epithelial tumors [161][130]. Moreover, researchers are adopting such patient-derived preclinical platforms to evaluate different strategies targeting immune checkpoint axes, alone or in combination. In this latter context, an association of an anti-PD-L1 mAb (atezolizumab) with MEK inhibitors (selumetinib) led to a higher MHC-I expression on non-small lung cancer organoids, together with increased secretion of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α by immune cells [162][131].

However, despite all the encouraging results derived from in vitro and in vivo preclinical models, many patients do not respond to some promising therapies, even due to the great variety of mechanisms involved in cancer immune evasion that are still not completely understood. Furthermore, although Matrigel establishes a favorable TME [163][132], it is affected by several drawbacks that considerably limit its use. Firstly, because of its structural weakness, it is mainly adopted as a monolayer or a thin gel conformation, principally for short-term invasion assays [143][112]. Then, the applicability of Matrigel is severely hampered because of its variability in composition and structure, due to its natural origin (e.g., tumor sizes from which is extracted, prepared, etc.) [147][116]. Differences in mechanical and biochemical properties between the various batches and within a single batch negatively impact the experimental reproducibility [147,164][116][133]. These constraints, along with the fact that Matrigel is difficult to manipulate physically and biochemically, make comparisons between and within laboratories remarkably challenging [164,165][133][134]. Moreover, being an animal-derived ECM, the presence of xenogenic contaminants may hamper the use of Matrigel-based cell cultures as in vitro preclinical tool for screening effective immunotherapies. For instance, lactate dehydrogenase elevating virus (LDHV), a mouse virus capable of infecting macrophage cells, possibly influencing both the immune system and tumor behavior, was detected in multiple batches of Matrigel [166][135].

All these considerations should be kept in mind when interpreting results based on Matrigel-assisted cell cultures, to distinguish biological effects caused by controlled experimental conditions or variables from the hydrogel itself [164][133].

Collagen is another biomaterial belonging to this category that is largely employed as an ECM-supporting matrix for 3D models, as it contains fundamental cellular adhesion domains (i.e., arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) peptide) that favor cell growth in vitro. It is commonly deposited by different cancer types during malignant progression, thus being an important component of the TME. In particular, matrices made of collagen type I promote, in vitro, uncontrolled cancer cell growth, the establishment of hypoxic regions, and angiogenesis, thus being particularly suitable to resemble key environmental properties of tumors [167,168][136][137]. Considering this, several studies have been conducted to reproduce the complexity of the TME by including, in 3D collagen constructs, cancer cells with components of the tumor stroma as well as immune cells in close contact with each other. Cell-to-cell contact is notably critical when evaluating the anticancer activity of cytotoxic lymphocytes, which requires direct interactions with tumors to efficiently kill malignant cells [169][138]. Moreover, as discussed before, an immune-mediated pro-tumoral action is frequently observed within the TME, particularly due to the presence of TAMs supporting cancer progression and resistance to chemotherapies. For example, macrophages co-cultured with breast cancer cells in a more in vivo-like environment led to a significant increase in oxygen consumption as well as in the secretion of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and IL-10, suggesting a synergistic crosstalk between different types of cells and indicating a tumor-promoting activity of immune cells colonizing tumors such as M2-polarized macrophages [170][139]. It was demonstrated that macrophages’ polarization towards an M2 phenotype is reached spontaneously in organotypic co-cultures including cancer cells and fibroblasts after three weeks, with a consequent reinforced proteolytic activity of the tumor cells through the increase in MMP2 and MMP9 production. Moreover, the same authors showed that organotypic co-cultures allow handling either M1 or M2 polarization via stimulation with IFN-γ and LPS or IL-4, respectively [171][140]. This can help to deeply elucidate the role of macrophages in the TME, where they can contemporarily show a tumor-promoting effect or exert an antitumor activity by attacking and eliminating cancer cells, depending on their polarized status [172][141]. Therefore, the importance of developing more reliable in vitro systems taking into account the complex reciprocal interactions occurring in vivo between malignant and non-malignant cells is evident. Recently, some platforms prepared the groundwork for the investigation of novel agents (e.g., immunotherapeutic antibodies) aimed at targeting the key cellular components of the TME (e.g., CAFs or TAMs) in a clinically relevant context [173][142].

Overall, collagen has been widely employed as an EMC-mimicking matrix in the field of cancer research, also due to its easy manipulation and low costs, making this biopolymer easily accessible to the scientific community [174][143]. Despite its intrinsic poor mechanical properties, it can be easily tuned by changing the concentration or adding synthetic crosslinking agents to finely tune its structure and stiffness based on the specific application [167,168,175][136][137][144]. However, because of its animal origin, as with Matrigel, it is affected by risks associated with biological materials, such as the batch-to-batch variability, that limit the reproducibility of the results [174][143].

2.1.2. Polysaccharide-Based Polymers

Polysaccharide-based biopolymers have been largely adopted as ECM-supporting matrices for in vitro cell culture since they are characterized by low immunogenicity as well as elevated biocompatibility [165][134]. Several biomaterials belonging to this group have been used to support cancer cells’ interactions with the immune system, especially focusing on those mechanisms occurring within the TME that promote tumor growth and metastasis [176][145]. Among these polymers, alginate is one of the most employed. Alginate, derived from brown seaweeds, presents a molecular structure comparable to that of polysaccharides found in vivo [177][146]. It is particularly suitable for the formation of cell-laden microspheres, allowing for obtaining a high number of replicates due to its easy manipulation, fast gelation, thermal stability, and low cost [165,167,177,178][134][136][146][147].

Alginate microencapsulation has also been used to explore the onset of either a proinflammatory or an immunosuppressive TME, especially focusing on the dynamic interactions occurring between the main cellular components that support the tumor malignant behavior [180][148]. In a 3D co-culture of non-small cell lung carcinoma cells with CAFs and monocytes, an accumulation of soluble factors (IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, CXCL1) was observed, promoting immune cell infiltration of the tumor and M2-like macrophage polarization. This polarization was characterized by the expression of the CD68, CD163, and CD206 markers and the production of the CCL22 and CCL24 chemokines [181][149].

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide derived from the partial deacetylation of chitin, which is abundantly available from different biological sources, being, for example, the main structural polymer of crustacean exoskeletons [177][146]. Due to its poor solubility in common solvents, the process of extraction of chitin is quite laborious, thus limiting its utilization. In general, chitosan offers a higher mechanical strength, and the possibility to be easily chemically modified, and to interact with other biomolecules due to the presence of reactive functional groups. Furthermore, it simply forms soft gels and crosslinks with other polymers [182,183][150][151]. Besides these characteristics, chitosan represents an effective alternative candidate for 3D cultures of cancer cells due to a structure similar to that of GAGs, one of the main constituents of the tumor ECM [177,184][146][152]. The chitosan and alginate (CA) combination has also been largely adopted to realize porous scaffolds that exhibit better mechanical strength and shape maintenance when compared to chitosan alone, because of the electrostatic contact between chitosan’s amine groups and alginate’s carboxyl groups [177,184][146][152]. Three-dimensional CA scaffolds provide a cost-effective feasible model to evaluate in vitro the interplays between tumors and the immune system in a clinically relevant context [185][153]. For example, these platforms can mimic the breast cancer TME. In this context, the inactivation of CAFs, which have been demonstrated to induce T cell suppression in breast tumor stroma [186][154], or combined gene therapies aimed at enhancing T cell infiltration and activation in the tumor milieu [187][155] may represent novel strategies for improving the efficacy of the current adoptive T cell therapies against breast cancer.

However, there are also different drawbacks associated with these types of biomaterials. For example, chitosan is characterized by poor mechanical properties [178][147], and alginate by a variable degradation rate. Moreover, the latter does not possess integrin-binding sites, thus often requiring chemical modification or conjugation with other bioactive polymers [167][136]. Indeed, extensive literature has been reported on the covalent functionalization of alginate with the RGDpeptide to favor cellular adhesion, proliferation, and migration [167,168,188,189][136][137][156][157].

In conclusion, natural polymers are highly suitable to recapitulate in vitro the main features of the native ECM. Nevertheless, they suffer from important limitations. Besides the aforementioned significant batch-to-batch variability (e.g., various mechanical and biochemical features, peptide or protein concentrations) and xenogeneic contaminations associated with polymers derived from an animal source, it is generally difficult to control scaffold degradation rates, possibly influencing cellular activity in unknown ways [144][113]. Moreover, natural polymers can be realized in a limited range of mechanical stiffness, porosity, or biochemical cues [145][114].

Therefore, the focus is shifting toward synthetic polymers that may mimic the biomimetic qualities of natural ones while providing more repeatability and control over the materials’ physical and chemical properties.

2.2. Synthetic Biomaterial-Based 3D Tools

Synthetic polymer-based scaffolds represent a valid alternative to naturally derived ones. First, being free of xenogeneic and possible contaminants, they enable high reproducibility by reducing inter-batch variations, thus resulting in a greater consistency of the results. Moreover, they can be more easily manipulated to finely tune mechanical and chemical properties as well as degradation rates for specific cell culture applications [144,164,178,190][113][133][147][158]. Indeed, even though synthetic biomaterials are biologically inert, allowing, but not promoting, cellular activity, cell adhesion ligands and other bioactive molecules can be precisely introduced via covalent attachment, adsorption, or electrostatic interactions depending on the desirable environmental cues that need to be investigated [145,178,190,191][114][147][158][159]. Therefore, emerging studies have demonstrated the possibility to adopt these polymers for investigating the interactions between cancer cells and the immune system within the TME in vitro. For instance, 3D polystyrene-based scaffolds have been used to mimic T cell infiltration in non-small lung cancer and to explore the subset of inflammation proteins related to the co-cultivation of tumor cells with lymphocytes [192][160], while polycaprolactone (PCL) has been exploited for examining the capability of DCs to engulf dying colon cancer cells through the same mechanisms observed in the human body [193][161].

One of the most common synthetic polymers is polyethylene glycol (PEG), which has been largely used in the tissue engineering field both in vitro and in vivo, showing to be highly suitable as a model for ECM–cancer interaction studies [145][114]. It is biocompatible and fully hydrated, thus closely reproducing the soft tissues’ characteristics, and particularly suitable for cell encapsulation due to the liquid-to-solid transition to form hydrogels encapsulating cells [184][152]. Even though it is biologically inert, it can be easily functionalized with protease-sensitive peptides to render the surrounding ECM enzymatically degradable by cells. Numerous studies have explored the inclusion, via crosslinking reactions, of different peptides sensitive to MMP-mediated cleavage, in order to evaluate cell migration and invasion [194,195][162][163]. The presence of MMP-cleavable sites in PEG hydrogels has also been shown to promote cell proliferation and differentiation [196,197,198,199][164][165][166][167]. Moreover, cellular adhesion and/or other molecules of interest (VEGF, TGF-β1, etc.) can been integrated through various non-toxic polymerization techniques [164,184,200][133][152][168]. Interestingly, in a recent study, the migration and function of NK-92 cells within a 3D RGD-functionalized PEG hydrogel containing either non-small lung cancer metastatic (H1299) or non-metastatic (A549) cell lines were investigated. The metastatic tumor model displayed a greater loss of stress ligands (ULBP1, MICA), downregulation of chemokine expression (MCP-1), and higher production of inhibitory soluble molecules (i.e., TGF-β, IL-6), as compared with a non-metastatic tumor model, more resembling the in vivo scenario. The NK cell migration toward cancer cells and their co-localization depended on the immunomodulatory profile of tumors, and NK-92 cells decreased the production of RANTES and MIP-1 α/β when incubated with H1299 cells. The study highlights the benefits of 3D cancer models that could examine the effects of signals on NK cell migration. In addition to the release of soluble substances, immune cell infiltration might be influenced by the physical features of tumors. Nevertheless, the impact of matrix stiffness on NK cell migration is unknown, and more research is needed to fully understand the NK cell mechanotransduction pathways [201][169].

Despite recent promising outcomes, PEG and other synthetic biomaterials are still poorly adopted in cancer research. Despite the fact the raw materials for making PEG hydrogels are about half the price of Matrigel, the necessity for one or more synthetic peptides to provide the essential biochemical cues to drive cellular behavior can be prohibitively expensive for large-scale manufacturing. Furthermore, extensive adjustments to obtain the desired combination of physical and biochemical properties driving cellular behavior can be time-consuming, costly, and challenging [164][133], whereas degradation products are often non-biocompatible [202][170]. Finally, when compared to in vivo tumors, cells cultivated in completely synthetic platforms can proliferate without some tumor-like gene expression patterns, revealing inconsistent tumorigenicity and metastatic potential, or resistance to anticancer treatments. As one might expect, such difficulties have an impact on the creation of reliable tumor-mimicking 3D in vitro models [167][136].

References

- Lee, J.Y.; Chaudhuri, O. Modeling the tumor immune microenvironment for drug discovery using 3D culture. APL Bioeng. 2021, 5, 010903.

- Shelton, S.E.; Nguyen, H.T.; Barbie, D.A.; Kamm, R.D. Engineering approaches for studying immune-tumor cell interactions and immunotherapy. iScience 2021, 24, 101985.

- Dunn, G.P.; Old, L.J.; Schreiber, R.D. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 22, 329–360.

- Bellora, F.; Castriconi, R.; Dondero, A.; Carrega, P.; Mantovani, A.; Ferlazzo, G.; Moretta, A.; Bottino, C. Human NK cells and NK receptors. Immunol. Lett. 2014, 161, 168–173.

- Thielens, A.; Vivier, E.; Romagné, F. NK cell MHC class I specific receptors (KIR): From biology to clinical intervention. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012, 24, 239–245.

- Kim, S.; Poursine-Laurent, J.; Truscott, S.M.; Lybarger, L.; Song, Y.-J.; Yang, L.; French, A.R.; Sunwoo, J.B.; Lemieux, S.; Hansen, T.H. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature 2005, 436, 709–713.

- Guia, S.; Fenis, A.; Vivier, E.; Narni-Mancinelli, E. Activating and inhibitory receptors expressed on innate lymphoid cells. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 331–341.

- Moretta, L.; Bottino, C.; Pende, D.; Castriconi, R.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, A. Surface NK receptors and their ligands on tumor cells. Semin. Immunol. 2006, 18, 151–158.

- Sivori, S.; Meazza, R.; Quintarelli, C.; Carlomagno, S.; Della Chiesa, M.; Falco, M.; Moretta, L.; Locatelli, F.; Pende, D. NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy for Hematological Malignancies. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1702.

- Balsamo, M.; Vermi, W.; Parodi, M.; Pietra, G.; Manzini, C.; Queirolo, P.; Lonardi, S.; Augugliaro, R.; Moretta, A.; Facchetti, F.; et al. Melanoma cells become resistant to NK-cell-mediated killing when exposed to NK-cell numbers compatible with NK-cell infiltration in the tumor. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 1833–1842.

- Kohrt, H.E.; Thielens, A.; Marabelle, A.; Sagiv-Barfi, I.; Sola, C.; Chanuc, F.; Fuseri, N.; Bonnafous, C.; Czerwinski, D.; Rajapaksa, A. Anti-KIR antibody enhancement of anti-lymphoma activity of natural killer cells as monotherapy and in combination with anti-CD20 antibodies. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2014, 123, 678–686.

- André, P.; Denis, C.; Soulas, C.; Bourbon-Caillet, C.; Lopez, J.; Arnoux, T.; Bléry, M.; Bonnafous, C.; Gauthier, L.; Morel, A. Anti-NKG2A mAb is a checkpoint inhibitor that promotes anti-tumor immunity by unleashing both T and NK cells. Cell 2018, 175, 1731–1743.

- Locatelli, F.; Pende, D.; Falco, M.; Della Chiesa, M.; Moretta, A.; Moretta, L. NK cells mediate a crucial graft-versus-leukemia effect in haploidentical-HSCT to cure high-risk acute leukemia. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 577–590.

- Bottino, C.; Dondero, A.; Castriconi, R. Inhibitory axes impacting on the activity and fate of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Mol. Asp. Med. 2021, 80, 100985.

- Chiossone, L.; Vienne, M.; Kerdiles, Y.M.; Vivier, E. Natural killer cell immunotherapies against cancer: Checkpoint inhibitors and more. Semin. Immunol. 2017, 31, 55–63.

- Sciumè, G.; Fionda, C.; Stabile, H.; Gismondi, A.; Santoni, A. Negative regulation of innate lymphoid cell responses in inflammation and cancer. Immunol. Lett. 2019, 215, 28–34.

- Marrella, A.; Dondero, A.; Aiello, M.; Casu, B.; Caluori, G.; Castriconi, R.; Scaglione, S. Cell-Laden Hydrogel as a Clinical-Relevant 3D Model for Analyzing Neuroblastoma Growth, Immunophenotype, and Susceptibility to Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1876.

- Scribner, J.A.; Brown, J.G.; Son, T.; Chiechi, M.; Li, P.; Sharma, S.; Li, H.; De Costa, A.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Preclinical Development of MGC018, a Duocarmycin-based Antibody–drug Conjugate Targeting B7-H3 for Solid Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 2235–2244.

- Gauthier, L.; Morel, A.; Anceriz, N.; Rossi, B.; Blanchard-Alvarez, A.; Grondin, G.; Trichard, S.; Cesari, C.; Sapet, M.; Bosco, F. Multifunctional natural killer cell engagers targeting NKp46 trigger protective tumor immunity. Cell 2019, 177, 1701–1713.

- Marofi, F.; Al-Awad, A.S.; Sulaiman Rahman, H.; Markov, A.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Ivanovna Enina, Y.; Mahmoodi, M.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Yazdanifar, M.; Stanley Chartrand, M. CAR-NK cell: A new paradigm in tumor immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 2078.

- Bottino, C.; Dondero, A.; Bellora, F.; Moretta, L.; Locatelli, F.; Pistoia, V.; Moretta, A.; Castriconi, R. Natural killer cells and neuroblastoma: Tumor recognition, escape mechanisms, and possible novel immunotherapeutic approaches. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 56.

- Castriconi, R.; Dondero, A.; Augugliaro, R.; Cantoni, C.; Carnemolla, B.; Sementa, A.R.; Negri, F.; Conte, R.; Corrias, M.V.; Moretta, L.; et al. Identification of 4Ig-B7-H3 as a neuroblastoma-associated molecule that exerts a protective role from an NK cell-mediated lysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12640–12645.

- Steinberger, P.; Majdic, O.; Derdak, S.V.; Pfistershammer, K.; Kirchberger, S.; Klauser, C.; Zlabinger, G.; Pickl, W.F.; Stöckl, J.; Knapp, W. Molecular Characterization of Human 4Ig-B7-H3, a Member of the B7 Family with Four Ig-Like Domains. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 2352–2359.

- Chapoval, A.I.; Ni, J.; Lau, J.S.; Wilcox, R.A.; Flies, D.B.; Liu, D.; Dong, H.; Sica, G.L.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; et al. B7-H3: A costimulatory molecule for T cell activation and IFN-γ production. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 269–274.

- Lemke, D.; Pfenning, P.N.; Sahm, F.; Klein, A.C.; Kempf, T.; Warnken, U.; Schnölzer, M.; Tudoran, R.; Weller, M.; Platten, M.; et al. Costimulatory protein 4IgB7H3 drives the malignant phenotype of glioblastoma by mediating immune escape and invasiveness. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 105–117.

- Prasad, D.V.R.; Nguyen, T.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Duong, J.; Wang, Y.; Dong, C. Murine B7-H3 is a negative regulator of T cells. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2500–2506.

- Suh, W.-K.; Gajewska, B.U.; Okada, H.; Gronski, M.A.; Bertram, E.M.; Dawicki, W.; Duncan, G.S.; Bukczynski, J.; Plyte, S.; Elia, A. The B7 family member B7-H3 preferentially down-regulates T helper type 1–mediated immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 899–906.

- Flem-Karlsen, K.; Fodstad, Ø.; Tan, M.; Nunes-Xavier, C.E. B7-H3 in cancer–beyond immune regulation. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 401–404.

- Ni, L.; Dong, C. New B7 family checkpoints in human cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1203–1211.

- Gregorio, A.; Corrias, M.V.; Castriconi, R.; Dondero, A.; Mosconi, M.; Gambini, C.; Moretta, A.; Moretta, L.; Bottino, C. Small round blue cell tumours: Diagnostic and prognostic usefulness of the expression of B7-H3 surface molecule. Histopathology 2008, 53, 73–80.

- Vallera, D.A.; Ferrone, S.; Kodal, B.; Hinderlie, P.; Bendzick, L.; Ettestad, B.; Hallstrom, C.; Zorko, N.A.; Rao, A.; Fujioka, N. NK-cell-mediated targeting of various solid tumors using a B7-H3 Tri-specific killer engager in vitro and in vivo. Cancers 2020, 12, 2659.

- Kendsersky, N.M.; Lindsay, J.; Kolb, E.A.; Smith, M.A.; Teicher, B.A.; Erickson, S.W.; Earley, E.J.; Mosse, Y.P.; Martinez, D.; Pogoriler, J.; et al. The B7-H3–Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate m276-SL-PBD Is Potently Effective Against Pediatric Cancer Preclinical Solid Tumor Models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 27, 221–237.e8.

- Majzner, R.G.; Theruvath, J.L.; Nellan, A.; Heitzeneder, S.; Cui, Y.; Mount, C.W.; Rietberg, S.P.; Linde, M.H.; Xu, P.; Rota, C.; et al. CAR T cells targeting B7-H3, a pan-cancer antigen, demonstrate potent preclinical activity against pediatric solid tumors and brain tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2560–2574.

- Du, H.; Hirabayashi, K.; Ahn, S.; Kren, N.P.; Montgomery, S.A.; Wang, X.; Tiruthani, K.; Mirlekar, B.; Michaud, D.; Greene, K.; et al. Antitumor Responses in the Absence of Toxicity in Solid Tumors by Targeting B7-H3 via Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 221–237.e8.

- Park, J.A.; Cheung, N.-K. V Targets and antibody formats for immunotherapy of neuroblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1836.

- Locati, M.; Mantovani, A.; Sica, A. Macrophage activation and polarization as an adaptive component of innate immunity. Adv. Immunol. 2013, 120, 163–184.

- Kim, B.G.; Malek, E.; Choi, S.H.; Ignatz-Hoover, J.J.; Driscoll, J.J. Novel therapies emerging in oncology to target the TGF-β pathway. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 55.

- Viel, S.; Marçais, A.; Guimaraes, F.S.; Loftus, R.; Rabilloud, J.; Grau, M.; Degouve, S.; Djebali, S.; Sanlaville, A.; Charrier, E. TGF-β inhibits the activation and functions of NK cells by repressing the mTOR pathway. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra19.

- Regis, S.; Dondero, A.; Caliendo, F.; Bottino, C.; Castriconi, R. NK Cell Function Regulation by TGF-β-Induced Epigenetic Mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 311.

- Castriconi, R.; Cantoni, C.; Della Chiesa, M.; Vitale, M.; Marcenaro, E.; Conte, R.; Biassoni, R.; Bottino, C.; Moretta, L.; Moretta, A. Transforming growth factor β1 inhibits expression of NKP30 and NKG2d receptors: Consequences for the NK-mediated killing of dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4120–4125.

- Mamessier, E.; Sylvain, A.; Thibult, M.-L.; Houvenaeghel, G.; Jacquemier, J.; Castellano, R.; Gonçalves, A.; André, P.; Romagné, F.; Thibault, G. Human breast cancer cells enhance self tolerance by promoting evasion from NK cell antitumor immunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3609–3622.

- Allan, D.S.J.; Rybalov, B.; Awong, G.; Zúñiga-Pflücker, J.C.; Kopcow, H.D.; Carlyle, J.R.; Strominger, J.L. TGF-β affects development and differentiation of human natural killer cell subsets. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 40, 2289–2295.

- Song, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, G.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.K.; Chung, W.Y.; Park, S.J.; Han, S.Y.; Cho, D.; et al. Transforming growth factor-ß1 regulates human renal proximal tubular epithelial cell susceptibility to natural killer cells via modulation of the NKG2D ligands. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1180–1188.

- Huang, C.H.; Liao, Y.J.; Chiou, T.J.; Huang, H.T.; Lin, Y.H.; Twu, Y.C. TGF-β regulated leukemia cell susceptibility against NK targeting through the down-regulation of the CD48 expression. Immunobiology 2019, 224, 649–658.

- Castriconi, R.; Carrega, P.; Dondero, A.; Bellora, F.; Casu, B.; Regis, S.; Ferlazzo, G.; Bottino, C. Molecular mechanisms directing migration and retention of natural killer cells in human tissues. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2324.

- Regis, S.; Caliendo, F.; Dondero, A.; Casu, B.; Romano, F.; Loiacono, F.; Moretta, A.; Bottino, C.; Castriconi, R. TGF-ß1 downregulates the expression of CX3CR1 by inducing miR-27a-5p in primary human NK cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 868.

- Cortez, V.S.; Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Robinette, M.L.; Bando, J.K.; Wang, Y.; Geiger, T.L.; Gilfillan, S.; Fuchs, A.; Vivier, E.; Sun, J.C. Transforming growth factor-β signaling guides the differentiation of innate lymphoid cells in salivary glands. Immunity 2016, 44, 1127–1139.

- Casu, B.; Dondero, A.; Regis, S.; Caliendo, F.; Petretto, A.; Bartolucci, M.; Bellora, F.; Bottino, C.; Castriconi, R. Novel immunoregulatory functions of IL-18, an accomplice of TGF-β1. Cancers 2019, 11, 75.

- Brownlie, D.; Doughty-Shenton, D.; Yh Soong, D.; Nixon, C.; Carragher, N.O.; Carlin, L.M.; Kitamura, T. Metastasis-associated macrophages constrain antitumor capability of natural killer cells in the metastatic site at least partially by membrane bound transforming growth factor β. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001740.

- Han, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.; Lin, C.; Pan, Z.; Zhou, W.; et al. Human hepatocellular carcinoma-infiltrating CD4+CD69 +Foxp3- regulatory T cell suppresses T cell response via membrane-bound TGF-β1. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 92, 539–550.

- Chen, W.J.; Jin, W.; Hardegen, N.; Lei, K.J.; Li, L.; Marinos, N.; McGrady, G.; Wahl, S.M. Conversion of Peripheral CD4+CD25− Naive T Cells to CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cells by TGF-β Induction of Transcription Factor Foxp3. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1875–1886.

- Fantini, M.C.; Becker, C.; Monteleone, G.; Pallone, F.; Galle, P.R.; Neurath, M.F. Cutting Edge: TGF-β Induces a Regulatory Phenotype in CD4+CD25− T Cells through Foxp3 Induction and Down-Regulation of Smad7. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 5149–5153.

- Nakamura, S.; Yaguchi, T.; Kawamura, N.; Kobayashi, A.; Sakurai, T.; Higuchi, H.; Takaishi, H.; Hibi, T.; Kawakami, Y. TGF-β1 in tumor microenvironments induces immunosuppression in the tumors and sentinel lymph nodes and promotes tumor progression. J. Immunother. 2014, 37, 63–72.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Tang, W.; Deng, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Shen, X. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Induce Regulatory T Cells and Lead to Poor Prognosis via Production of Transforming Growth Factor-β1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 306–318.

- Soares, K.C.; Rucki, A.A.; Kim, V.; Foley, K.; Solt, S.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Jaffee, E.M.; Zheng, L. TGF-β blockade depletes T regulatory cells from metastatic pancreatic tumors in a vaccine dependent manner. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 43005–43015.

- Budhu, S.; Schaer, D.; Li, Y.; Houghton, A.; Silverstein, S.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J. Blockade of surface bound TGF-β on regulatory T cells abrogates suppression of effector T cell function within the tumor microenvironment (TUM2P. 1015). J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 69.12.

- Hugo, W.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Song, C.; Moreno, B.H.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Pang, J.; Chmielowski, B.; Cherry, G.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Features of Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma. Cell 2016, 165, 35–44.

- Bai, X.; Yi, M.; Jiao, Y.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K. Blocking tgf-β signaling to enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2019, 12, 9527–9538.

- Martin, C.J.; Datta, A.; Littlefield, C.; Kalra, A.; Chapron, C.; Wawersik, S.; Dagbay, K.B.; Brueckner, C.T.; Nikiforov, A.; Danehy, F.T. Selective inhibition of TGFβ1 activation overcomes primary resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy by altering tumor immune landscape. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay8456.

- Kloss, C.C.; Lee, J.; Zhang, A.; Chen, F.; Melenhorst, J.J.; Lacey, S.F.; Maus, M.V.; Fraietta, J.A.; Zhao, Y.; June, C.H. Dominant-Negative TGF-β Receptor Enhances PSMA-Targeted Human CAR T Cell Proliferation And Augments Prostate Cancer Eradication. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 1855–1866.

- Tang, N.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, M.; Li, N.; Mu, W.; Wei, X.F.; Han, W.; Wang, H. TGF-β inhibition via CRISPR promotes the long-term efficacy of CAR T cells against solid tumors. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e133977.

- Ravi, R.; Noonan, K.A.; Pham, V.; Bedi, R.; Zhavoronkov, A.; Ozerov, I.V.; Makarev, E.; Artemov, A.V.; Wysocki, P.T.; Mehra, R.; et al. Bifunctional immune checkpoint-targeted antibody-ligand traps that simultaneously disable TGFβ enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 741.

- Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Qu, Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, J.; Dunn, Z.S.; Cinay, G.E.; MacMullan, M.A.; Hu, F.; et al. Secretion of bispecific protein of anti-PD-1 fused with TGF-β trap enhances antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy. Mol. Ther.-Oncolytics 2021, 21, 144–157.

- Li, L.; Yu, R.; Cai, T.; Chen, Z.; Lan, M.; Zou, T.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y. Effects of immune cells and cytokines on inflammation and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 88, 106939.

- Vitale, M.; Cantoni, C.; Pietra, G.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, L. Effect of tumor cells and tumor microenvironment on NK-cell function. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 1582–1592.

- Mannino, M.H.; Zhu, Z.; Xiao, H.; Bai, Q.; Wakefield, M.R.; Fang, Y. The paradoxical role of IL-10 in immunity and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 367, 103–107.

- Konjević, G.M.; Vuletić, A.M.; Mirjačić Martinović, K.M.; Larsen, A.K.; Jurišić, V.B. The role of cytokines in the regulation of NK cells in the tumor environment. Cytokine 2019, 117, 30–40.

- Ma, Y.; Bauer, V.; Riedel, T.; Ahmetlić, F.; Hömberg, N.; Hofer, T.P.; Röcken, M.; Mocikat, R. Interleukin-10 counteracts T-helper type 1 responses in B-cell lymphoma and is a target for tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2021, 503, 110–116.

- Michielon, E.; López González, M.; Burm, J.L.A.; Waaijman, T.; Jordanova, E.S.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Gibbs, S. Micro-environmental cross-talk in an organotypic human melanoma-in-skin model directs M2-like monocyte differentiation via IL-10. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 2319–2331.

- Balsamo, M.; Scordamaglia, F.; Pietra, G.; Manzini, C.; Cantoni, C.; Boitano, M.; Queirolo, P.; Vermi, W.; Facchetti, F.; Moretta, A.; et al. Melanoma-associated fibroblasts modulate NK cell phenotype and antitumor cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20847–20852.

- Olesch, C.; Sha, W.; Angioni, C.; Sha, L.K.; Açaf, E.; Patrignani, P.; Jakobsson, P.J.; Radeke, H.H.; Grösch, S.; Geisslinger, G.; et al. MPGES-1-derived PGE2 suppresses CD80 expression on tumorassociated phagocytes to inhibit anti-tumor immune responses in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10284–10296.

- Pennock, N.D.; Martinson, H.A.; Guo, Q.; Betts, C.B.; Jindal, S.; Tsujikawa, T.; Coussens, L.M.; Borges, V.F.; Schedin, P. Ibuprofen supports macrophage differentiation, T cell recruitment, and tumor suppression in a model of postpartum breast cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 98.

- Xun, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Hu, S.; Xiang, X.; Cheng, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J. Cyclooxygenase-2 expressed hepatocellular carcinoma induces cytotoxic T lymphocytes exhaustion through M2 macrophage polarization. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 4360–4375.

- Wang, Y.; Cui, L.; Georgiev, P.; Singh, L.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Grein, J.; Zhang, C.; Muise, E.S.; Sloman, D.L.; et al. Combination of EP4 antagonist MF-766 and anti-PD-1 promotes anti-tumor efficacy by modulating both lymphocytes and myeloid cells. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1896643.

- Lai, Y.H.; Liu, H.; Chiang, W.F.; Chen, T.W.; Chu, L.J.; Yu, J.S.; Chen, S.J.; Chen, H.C.; Tan, B.C.M. MiR-31-5p-ACOX1 axis enhances tumorigenic fitness in oral squamous cell carcinoma via the promigratory prostaglandin E2. Theranostics 2018, 8, 486–504.

- Munn, D.H.; Shafizadeh, E.; Attwood, J.T.; Bondarev, I.; Pashine, A.; Mellor, A.L. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 189, 1363–1372.

- Munn, D.H.; Sharma, M.D.; Baban, B.; Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Ron, D.; Mellor, A.L. GCN2 kinase in T cells mediates proliferative arrest and anergy induction in response to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Immunity 2005, 22, 633–642.

- Mezrich, J.D.; Fechner, J.H.; Zhang, X.; Johnson, B.P.; Burlingham, W.J.; Bradfield, C.A. An Interaction between Kynurenine and the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Can Generate Regulatory T Cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 3190–3198.

- Gandhi, R.; Kumar, D.; Burns, E.J.; Nadeau, M.; Dake, B.; Laroni, A.; Kozoriz, D.; Weiner, H.L.; Quintana, F.J. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces human type 1 regulatory T cell-like and Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 846–853.

- Nguyen, N.T.; Kimura, A.; Nakahama, T.; Chinen, I.; Masuda, K.; Nohara, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Kishimoto, T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor negatively regulates dendritic cell immunogenicity via a kynurenine-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19961–19966.

- Wagage, S.; John, B.; Krock, B.L.; Hall, A.O.; Randall, L.M.; Karp, C.L.; Simon, M.C.; Hunter, C.A. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Promotes IL-10 Production by NK Cells. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 1661–1670.

- Liu, Y.; Liang, X.; Dong, W.; Fang, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhang, T.; Fiskesund, R.; Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Yin, X.; et al. Tumor-Repopulating Cells Induce PD-1 Expression in CD8+ T Cells by Transferring Kynurenine and AhR Activation. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 480–494.e7.

- Della Chiesa, M.; Carlomagno, S.; Frumento, G.; Balsamo, M.; Cantoni, C.; Conte, R.; Moretta, L.; Moretta, A.; Vitale, M. The tryptophan catabolite L-kynurenine inhibits the surface expression of NKp46- and NKG2D-activating receptors and regulates NK-cell function. Blood 2006, 108, 4118–4125.

- Labadie, B.W.; Bao, R.; Luke, J.J. Reimagining IDO pathway inhibition in cancer immunotherapy via downstream focus on the tryptophan–kynurenine–aryl hydrocarbon axis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1462–1471.

- Vultaggio-Poma, V.; Sarti, A.C.; Di Virgilio, F. Extracellular ATP: A Feasible Target for Cancer Therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 2496.

- Dosch, M.; Gerber, J.; Jebbawi, F.; Beldi, G. Mechanisms of ATP release by inflammatory cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1222.

- Ohta, A. A metabolic immune checkpoint: Adenosine in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 109.

- Antonioli, L.; Pacher, P.; Vizi, E.S.; Haskó, G. CD39 and CD73 in immunity and inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 355–367.

- Churov, A.; Zhulai, G. Targeting adenosine and regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Hum. Immunol. 2021, 82, 270–278.

- Clayton, A.; Al-Taei, S.; Webber, J.; Mason, M.D.; Tabi, Z. Cancer Exosomes Express CD39 and CD73, Which Suppress T Cells through Adenosine Production. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 676–683.

- Cekic, C.; Day, Y.J.; Sag, D.; Linden, J. Myeloid expression of adenosine a2A receptor suppresses T and NK cell responses in the solid tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 7250–7259.

- Vaupel, P.; Mayer, A. Hypoxia-driven adenosine accumulation: A crucial microenvironmental factor promoting tumor progression. In Oxygen Transport to Tissue XXXVII; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 177–183.

- Antonioli, L.; Fornai, M.; Blandizzi, C.; Pacher, P.; Haskó, G. Adenosine signaling and the immune system: When a lot could be too much. Immunol. Lett. 2019, 205, 9–15.

- Chen, S.; Akdemir, I.; Fan, J.; Linden, J.; Zhang, B.; Cekic, C. The expression of adenosine A2B receptor on antigen-presenting cells suppresses CD8+T-cell responses and promotes tumor growth. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1064–1074.

- Ohta, A.; Kini, R.; Ohta, A.; Subramanian, M.; Madasu, M.; Sitkovsky, M. The development and immunosuppressive functions of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are under influence of the adenosine-A2A adenosine receptor pathway. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 190.

- Riabov, V.; Gudima, A.; Wang, N.; Mickley, A.; Orekhov, A.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Role of tumor associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 75.

- Balta, E.; Wabnitz, G.H.; Samstag, Y. Hijacked immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: Molecular mechanisms of immunosuppression and cues to improve t cell-based immunotherapy of solid tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5736.

- Piccard, H.; Muschel, R.J.; Opdenakker, G. On the dual roles and polarized phenotypes of neutrophils in tumor development and progression. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2012, 82, 296–309.

- Masucci, M.T.; Minopoli, M.; Carriero, M.V. Tumor Associated Neutrophils. Their Role in Tumorigenesis, Metastasis, Prognosis and Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1146.

- Hoh, A.; Dewerth, A.; Vogt, F.; Wenz, J.; Baeuerle, P.A.; Warmann, S.W. The activity of cd T cells against paediatric liver tumour cells and spheroids in cell culture. Liver Int. 2013, 33, 127–136.

- Varesano, S.; Zocchi, M.R.; Poggi, A. Zoledronate Triggers V δ 2 T Cells to Destroy and Kill Spheroids of Colon Carcinoma: Quantitative Image Analysis of Three-Dimensional Cultures. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 998.

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, M.; Meng, F.; Shao, J.; Xu, Q.; Wei, J.; Liu, B. Evaluation of PD-1 blockade using a multicellular tumor spheroid model. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 7471–7478.

- Koeck, S.; Kern, J.; Zwierzina, M.; Gamerith, G.; Lorenz, E.; Sopper, S.; Zwierzina, H.; Amann, A.; Koeck, S.; Kern, J.; et al. The influence of stromal cells and tumor- microenvironment-derived cytokines and chemokines on CD3 CD8 tumor infiltrating lymphocyte subpopulations. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1323617.

- Giannattasio, A.; Weil, S.; Kloess, S.; Ansari, N.; Stelzer, E.H.K.; Cerwenka, A.; Steinle, A.; Koehl, U.; Koch, J. Cytotoxicity and infiltration of human NK cells in in vivo- like tumor spheroids. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 351.

- Evert, J.S.H.; Cany, J.; Van Den Brand, D.; Brock, R.; Torensma, R.; Bekkers, R.L.; Joop, H.; Massuger, L.F.; Dolstra, H.; Evert, J.S.H.; et al. Umbilical cord blood CD34 progenitor-derived NK cells efficiently kill ovarian cancer spheroids and intraperitoneal tumors in NOD/SCID/IL2Rg mice. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1320630.

- Sherman, H.; Gitschier, H.J.; Rossi, A.E.; Rossi, A.E. A Novel three-dimensional Immune oncology Model for high-throughput testing of tumoricidal Activity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 857.

- Courau, T.; Bonnereau, J.; Chicoteau, J.; Bottois, H.; Remark, R.; Miranda, L.A.; Toubert, A.; Blery, M.; Aparicio, T.; Allez, M.; et al. Cocultures of human colorectal tumor spheroids with immune cells reveal the therapeutic potential of MICA / B and NKG2A targeting for cancer treatment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 9, 74.

- Ong, S.; Tan, Y.; Beretta, O.; Jiang, D.; Yeap, W.; Tai, J.J.Y.; Wong, W.; Yang, H.; Schwarz, H.; Lim, K.; et al. Macrophages in human colorectal cancer are pro-inflammatory and prime T cells towards an anti-tumour type-1 inflammatory response. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 89–100.

- Kuen, J.; Darowski, D.; Kluge, T.; Majety, M. Pancreatic cancer cell / fibroblast co-culture induces M2 like macrophages that influence therapeutic response in a 3D model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182039.

- Raghavan, S.; Mehta, P.; Xie, Y.; Lei, Y.L.; Mehta, G. Ovarian cancer stem cells and macrophages reciprocally interact through the WNT pathway to promote pro-tumoral and malignant phenotypes in 3D engineered microenvironments. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 1, 190.

- Vitale, C.; Fedi, A.; Marrella, A.; Varani, G.; Fato, M.; Scaglione, S. 3D perfusable hydrogel recapitulating the cancer dynamic environment to in vitro investigate metastatic colonization. Polymers 2020, 12, 2467.

- Cavo, M.; Caria, M.; Pulsoni, I.; Beltrame, F.; Fato, M.; Scaglione, S. A new cell-laden 3D Alginate-Matrigel hydrogel resembles human breast cancer cell malignant morphology, spread and invasion capability observed “in vivo”. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5333.

- Sayd, T.; El Hamoui, O.; Alies, B.; Gaudin, K.; Lespes, G.; Battu, S. Biomaterials for Three-Dimensional Cell Culture: From Applications in Oncology to Nanotechnology. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 481.

- Liu, Z.; Vunjak-novakovic, G. ScienceDirect Modeling tumor microenvironments using custom-designed biomaterial scaffolds. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2016, 11, 94–105.

- Monteiro, M.V.; Gaspar, V.M.; Ferreira, L.P.; Mano, J.F. Hydrogel 3D: In vitro tumor models for screening cell aggregation mediated drug response. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 1855–1864.

- Benton, G.; Arnaoutova, I.; George, J.; Kleinman, H.K.; Koblinski, J. Matrigel: From discovery and ECM mimicry to assays and models for cancer research. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 79, 3–18.

- West, N.R.; Kost, S.E.; Martin, S.D.; Milne, K.; Deleeuw, R.J.; Nelson, B.H.; Watson, P.H. Tumour-infiltrating FOXP3+ lymphocytes are associated with cytotoxic immune responses and good clinical outcome in oestrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 155–162.

- Augustine, T.N.; Dix-Peek, T.; Duarte, R.; Candy, G.P. Establishment of a heterotypic 3D culture system to evaluate the interaction of TREG lymphocytes and NK cells with breast cancer. J. Immunol. Methods 2015, 426, 1–13.

- Chimal-Ramírez, G.K.; Espinoza-Sánchez, N.A.; Utrera-Barillas, D.; Benítez-Bribiesca, L.; Velázquez, J.R.; Arriaga-Pizano, L.A.; Monroy-García, A.; Reyes-Maldonado, E.; Domínguez-López, M.L.; Piña-Sánchez, P.; et al. MMP1, MMP9, and COX2 expressions in promonocytes are induced by breast cancer cells and correlate with collagen degradation, transformation-like morphological changes in MCF-10A acini, and tumor aggressiveness. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 279505.

- Espinoza-Sánchez, N.A.; Chimal-Ramírez, G.K.; Mantilla, A.; Fuentes-Pananá, E.M. IL-1β, IL-8, and Matrix Metalloproteinases-1, -2, and -10 Are Enriched upon Monocyte–Breast Cancer Cell Cocultivation in a Matrigel-Based Three-Dimensional System. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 205.

- Denton, A.E.; Roberts, E.W.; Fearon, D.T. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment. Stromal Immunol. 2018, 1060, 99–114.

- Bussard, K.M.; Mutkus, L.; Stumpf, K.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; Marini, F.C. Tumor-associated stromal cells as key contributors to the tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 84.

- Dijkstra, K.K.; Cattaneo, C.M.; Weeber, F.; Chalabi, M.; van de Haar, J.; Fanchi, L.F.; Slagter, M.; van der Velden, D.L.; Kaing, S.; Kelderman, S.; et al. Generation of Tumor-Reactive T Cells by Co-culture of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Tumor Organoids. Cell 2018, 174, 1586–1598.e12.

- Kleinman, H.K.; Martin, G.R. Matrigel: Basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005, 15, 378–386.

- Finnberg, N.K.; Gokare, P.; Lev, A.; Grivennikov, S.I.; MacFarlane, A.W.; Campbell, K.S.; Winters, R.M.; Kaputa, K.; Farma, J.M.; Abbas, A.E.-S.; et al. Application of 3D tumoroid systems to define immune and cytotoxic therapeutic responses based on tumoroid and tissue slice culture molecular signatures. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 66747–66757.

- Shamir, E.R.; Ewald, A.J. Three-dimensional organotypic culture: Experimental models of mammalian biology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 647–664.

- Tsai, S.; McOlash, L.; Palen, K.; Johnson, B.; Duris, C.; Yang, Q.; Dwinell, M.B.; Hunt, B.; Evans, D.B.; Gershan, J.; et al. Development of primary human pancreatic cancer organoids, matched stromal and immune cells and 3D tumor microenvironment models. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 335.

- Braham, M.V.J.; Minnema, M.C.; Aarts, T.; Sebestyen, Z.; Straetemans, T.; Vyborova, A.; Kuball, J.; Öner, F.C.; Robin, C.; Alblas, J. Cellular immunotherapy on primary multiple myeloma expanded in a 3D bone marrow niche model. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1434465.

- Schnalzger, T.E.; Groot, M.H.; Zhang, C.; Mosa, M.H.; Michels, B.E.; Röder, J.; Darvishi, T.; Wels, W.S.; Farin, H.F. 3D model for CAR -mediated cytotoxicity using patient-derived colorectal cancer organoids. EMBO J. 2019, 38, 1–15.

- Gan, H.K.; Cvrljevic, A.N.; Johns, T.G. The epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII): Where wild things are altered. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 5350–5370.

- Della Corte, C.M.; Barra, G.; Ciaramella, V.; Di Liello, R.; Vicidomini, G.; Zappavigna, S.; Luce, A.; Abate, M.; Fiorelli, A.; Caraglia, M.; et al. Antitumor activity of dual blockade of PD-L1 and MEK in NSCLC patients derived three-dimensional spheroid cultures. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 253.

- Edsparr, K.; Basse, P.H.; Goldfarb, R.H.; Albertsson, P. Matrix metalloproteinases in cytotoxic lymphocytes impact on tumour infiltration and immunomodulation. Cancer Microenviron. 2011, 4, 351–360.

- Aisenbrey, E.A.; Murphy, W.L. Synthetic alternatives to Matrigel. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 539–551.

- Carvalho, M.R.; Lima, D.; Reis, R.L.; Correlo, V.M.; Oliveira, J.M. Evaluating Biomaterial- and Microfluidic-Based 3D Tumor Models. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 667–678.

- Peterson, N.C. From bench to Cageside: Risk assessment for rodent pathogen contamination of cells and biologics. ILAR J. 2012, 53, 310–314.

- Ferreira, L.P.; Gaspar, V.M.; Mano, J.F. Design of spherically structured 3D in vitro tumor models -Advances and prospects. Acta Biomater. 2018, 75, 11–34.

- Utech, S.; Boccaccini, A.R. A review of hydrogel-based composites for biomedical applications: Enhancement of hydrogel properties by addition of rigid inorganic fillers. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 271–310.

- Lin, Y.N.; Nasir, A.; Camacho, S.; Berry, D.L.; Schmidt, M.O.; Pearson, G.W.; Riegel, A.T.; Wellstein, A. Monitoring cancer cell invasion and t-cell cytotoxicity in 3d culture. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 2020, 61392.

- Tevis, K.M.; Cecchi, R.J.; Colson, Y.L.; Grinstaff, M.W. Mimicking the tumor microenvironment to regulate macrophage phenotype and assessing chemotherapeutic efficacy in embedded cancer cell/macrophage spheroid models. Acta Biomater. 2017, 50, 271–279.

- Linde, N.; Gutschalk, C.M.; Hoffmann, C.; Yilmaz, D.; Mueller, M.M. Integrating macrophages into organotypic co-cultures: A 3D in vitro model to study tumor-associated macrophages. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40058.

- Liu, X.Q.; Kiefl, R.; Roskopf, C.; Tian, F.; Huber, R.M. Interactions among lung cancer cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages in 3D co-cultures and the impact on MMP-1 and VEGF expression. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156268.

- Foxall, R.; Narang, P.; Glaysher, B.; Hub, E.; Teal, E.; Coles, M.C.; Ashton-Key, M.; Beers, S.A.; Cragg, M.S. Developing a 3D B Cell Lymphoma Culture System to Model Antibody Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 605231.

- Ravi, M.; Paramesh, V.; Kaviya, S.R.; Anuradha, E.; Paul Solomon, F.D. 3D cell culture systems: Advantages and applications. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 16–26.

- Szot, C.S.; Buchanan, C.F.; Freeman, J.W.; Rylander, M.N. 3D in vitro bioengineered tumors based on collagen I hydrogels. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7905–7912.

- Lu, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Q.; Cuiju, M.; Huang, L. Type conversion of secretomes in a 3D TAM2 and HCC cell co-culture system and functional importance of CXCL2 in HCC. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24558.

- Nii, T.; Makino, K.; Tabata, Y. Three-Dimensional Culture System of Cancer Cells Combined with Biomaterials for Drug Screening. Cancers 2020, 12, 2754.

- Ahadian, S.; Civitarese, R.; Bannerman, D.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Lu, R.; Wang, E.; Davenport-huyer, L.; Lai, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Y. Organ-On-A-Chip Platforms: A Convergence of Advanced Materials, Cells, and Microscale Technologies. Adv. Healtch. Mater. 2017, 7, 1700506.

- Rama-Esendagli, D.; Esendagli, G.; Yilmaz, G.; Guc, D. Spheroid formation and invasion capacity are differentially influenced by co-cultures of fibroblast and macrophage cells in breast cancer. Mol. Biol. 2014, 41, 2885–2892.

- Rebelo, P.; Pinto, C.; Martins, T.R.; Harrer, N.; Alves, P.M.; Estrada, M.F.; Loza-alvarez, P.; Gualda, E.J.; Sommergruber, W.; Brito, C. Biomaterials 3D-3-culture: A tool to unveil macrophage plasticity in the tumour microenvironment. Biomaterials 2018, 163, 185–197.

- Joseph, S.M.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Paranthaman, R.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. A review on source-specific chemistry, functionality, and applications of chitin and chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100036.

- Ahmad, S.I.; Ahmad, R.; Khan, M.S.; Kant, R.; Shahid, S.; Gautam, L.; Hasan, G.M.; Hassan, M.I. Chitin and its derivatives: Structural properties and biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 526–539.

- Thakuri, P.S.; Liu, C.; Luker, G.D.; Tavana, H. Biomaterials-Based Approaches to Tumor Spheroid and Organoid Modeling. Adv. Healtch. Mater. 2018, 7, 1700980.

- Florczyk, S.J.; Liu, G.; Kievit, F.M.; Lewis, A.M.; Wu, J.D.; Zhang, M. 3D Porous Chitosan—Alginate Scaffolds: A New Matrix for Studying Prostate Cancer Cell—Lymphocyte Interactions In Vitro. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2012, 1, 590–599.

- Phan-Lai, V.; Florczyk, S.J.; Kievit, F.M.; Wang, K.; Gad, E.; Disis, M.L.; Zhang, M. Three-Dimensional Scaffolds to Evaluate Tumor Associated Fibroblast-Mediated Suppression of Breast Tumor Specific T Cells. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1330–1337.