Tackling street gangs has recently been highlighted as a priority for public health. In this paper, the four components of a public health approach were reviewed: (1) surveillance, (2) identifying risk and protective factors, (3) developing and evaluating interventions at primary prevention, secondary prevention, and tertiary intervention stages, and (4) implementation of evidence-based programs. Findings regarding the effectiveness of prevention and intervention programs for street gang members were mixed, with unclear goals/objectives, limited theoretical foundation, and a lack of consistency in program implementation impeding effectiveness at reducing street gang involvement. The Good Lives Model was proposed as a framework for street gang intervention.

- street gang

- intervention

- Good Lives Model

- public health

1. Introduction

Definition

Tackling street gangs has recently been highlighted as a priority for public health. In this paper, the four components of a public health approach were reviewed: (1) surveillance, (2) identifying risk and protective factors, (3) developing and evaluating interventions at primary prevention, secondary prevention, and tertiary intervention stages, and (4) implementation of evidence-based programs. Findings regarding the effectiveness of prevention and intervention programs for street gang members were mixed, with unclear goals/objectives, limited theoretical foundation, and a lack of consistency in program implementation impeding effectiveness at reducing street gang involvement.

1. Introduction

Street gangs are a growing problem internationally, with countries including the UK, USA, Sweden, China, and the Netherlands reporting a marked increase in street gang membership (e.g., Chui and Khiatani 2018 [1]; Roks and Densley 2020 [2]; Rostami 2017 [3]). In the UK alone, the number of street gang affiliated youths has seen a dramatic increase over a five-year period. The Children's Commissioner [4] approximated that in 2013/14, 46,000 young people were either directly gang-involved or knew a street gang member. By 2019 this figure had increased to 27,000 full street gang members, 60,000 affiliates, and a further 313,000 youths who knew a street gang member [5]. Similar increases have been seen in the USA, with a 40.83% growth in the number of different street gangs between 2002 and 2012 [6]. As such, the World Health Organization [7] has highlighted youth violence, including street gang membership, as a global public health problem that requires an immediate international response.

Street gangs are a growing problem internationally, with countries including the UK, USA, Sweden, China, and the Netherlands reporting a marked increase in street gang membership (e.g., Chui and Khiatani 2018; Roks and Densley 2020; Rostami 2017). In the UK alone, the number of street gang affiliated youths has seen a dramatic increase over a five-year period. The Children’s Commissioner (2017) approximated that in 2013/14, 46,000 young people were either directly gang-involved or knew a street gang member. By 2019 this figure had increased to 27,000 full street gang members, 60,000 affiliates, and a further 313,000 youths who knew a street gang member (Children’s Commissioner 2019). Similar increases have been seen in the USA, with a 40.83% growth in the number of different street gangs between 2002 and 2012 (National Gang Center 2020). As such, the World Health Organization (World Health Organization 2020) has highlighted youth violence, including street gang membership, as a global public health problem that requires an immediate international response.

Street gang membership is associated with increased perpetration of illegal activities, particularly serious and violent offences [8], with this relationship stable across time, place, and definitions of street gangs [9]. As such, street gangs are responsible for causing heightened levels of fear and victimization amongst members of their community [10]. In addition, street gang involvement has adverse health, welfare, and economic consequences for individual members, which persist long after disengagement [11][12]. For instance, longitudinal research identified that adults who belonged to a street gang during adolescence experienced more mental and physical health issues than their non-gang counterparts [13]. Adolescent street gang members also experience more economic hardship during adulthood than their non-gang peers, with higher rates of unemployment and reliance on welfare benefits or illicit income [14]. Furthermore, street gang involvement during adolescence has a detrimental effect on the development of long-term stable family relationships, with former members more likely to engage in intimate partner violence and child maltreatment [15].

Street gang membership is associated with increased perpetration of illegal activities, particularly serious and violent offences (Pyrooz et al. 2016), with this relationship stable across time, place, and definitions of street gangs (Dong and Krohn 2016). As such, street gangs are responsible for causing heightened levels of fear and victimization amongst members of their community (Howell 2007). In addition, street gang involvement has adverse health, welfare, and economic consequences for individual members, which persist long after disengagement (Connolly and Jackson 2019; Petering 2016). For instance, longitudinal research identified that adults who belonged to a street gang during adolescence experienced more mental and physical health issues than their non-gang counterparts (Gilman et al. 2014). Adolescent street gang members also experience more economic hardship during adulthood than their non-gang peers, with higher rates of unemployment and reliance on welfare benefits or illicit income (Krohn et al. 2011). Furthermore, street gang involvement during adolescence has a detrimental effect on the development of long-term stable family relationships, with former members more likely to engage in intimate partner violence and child maltreatment (Augustyn et al. 2014).

Considering these long-term and wide-ranging effects of street gang membership, it is unsurprising that there has been a proliferation of prevention and intervention programs developed and implemented world-wide. Although literature is beginning to emerge which suggests some of these are effective programs at reducing street gang involvement, there remains a paucity of reliable evidence to date. Highlighted by Wong et al. [16] such programs often suffer from a lack of theoretical foundation [17], clear goals and objectives [18], and methodologically sound evaluation [19]. These factors are associated with an increased risk of harmful outcomes for program participants [20], including negative labeling and heightened rates of recidivism [21]. Thus, discovering “what works” in street gang prevention and intervention is essential.

Considering these long-term and wide-ranging effects of street gang membership, it is unsurprising that there has been a proliferation of prevention and intervention programs developed and implemented world-wide. Although literature is beginning to emerge which suggests some of these are effective programs at reducing street gang involvement, there remains a paucity of reliable evidence to date. Highlighted by Wong et al. (2011). such programs often suffer from a lack of theoretical foundation (McGloin and Decker 2010), clear goals and objectives (Klein and Maxson 2006), and methodologically sound evaluation (Curry 2010). These factors are associated with an increased risk of harmful outcomes for program participants (Welsh and Rocque 2014), including negative labeling and heightened rates of recidivism (Petrosino et al. 2010). Thus, discovering “what works” in street gang prevention and intervention is essential.

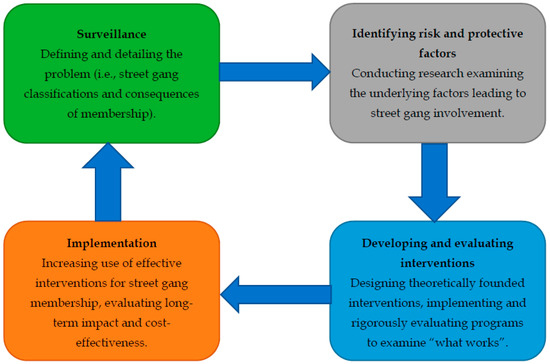

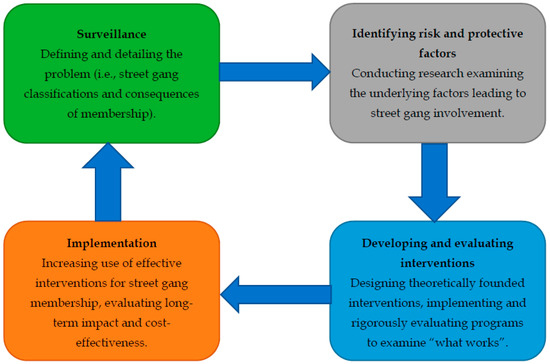

A public health approach to street gang membership has recently been suggested [22], which could guide the development of effective prevention and intervention strategies. WHO [23] suggests four key elements for a public health approach, including: (1) surveillance, (2) identifying risk and protective factors, (3) developing and evaluating interventions, and (4) implementation. See

A public health approach to street gang membership has recently been suggested (Gebo 2016), which could guide the development of effective prevention and intervention strategies. WHO (Krug et al. 2002) suggests four key elements for a public health approach, including: (1) surveillance, (2) identifying risk and protective factors, (3) developing and evaluating interventions, and (4) implementation. See

Figure 1 for an overview of each of these elements in relation to street gang prevention and intervention. Using a public health approach, street gang intervention occurs across three levels [24]: primary prevention (early intervention approaches prior to initiation of street gang involvement), secondary prevention (interventions specifically for individuals at-risk of street gang involvement), and tertiary prevention (long-term rehabilitation strategies for those who have engaged in street gangs). In addition, public health interventions can be universally implemented (aimed at the general population), selected (targeted towards those at-risk of street gang involvement), or indicated (targeted specifically at street gang members).

for an overview of each of these elements in relation to street gang prevention and intervention. Using a public health approach, street gang intervention occurs across three levels (Conaglen and Gallimore 2014): primary prevention (early intervention approaches prior to initiation of street gang involvement), secondary prevention (interventions specifically for individuals at-risk of street gang involvement), and tertiary prevention (long-term rehabilitation strategies for those who have engaged in street gangs). In addition, public health interventions can be universally implemented (aimed at the general population), selected (targeted towards those at-risk of street gang involvement), or indicated (targeted specifically at street gang members).

Figure 1. WHO's public health approach to violence prevention [23], adapted for street gang intervention.

2. Surveillance

Surveillance is a core aspect of a public health approach, which informs the development and implementation of prevention and intervention programs [25]. Surveillance involves establishing clear definitions regarding the population of interest (i.e., street gang members), enabling the identification of both those in need of intervention and the associated risk factors [26]. By implementing surveillance measures, such as analyzing knife crime and criminal convictions data, the extent of the problem in society on a local, national, and international scale can be recognized [27]. Ongoing monitoring enables any changes in the patterns or frequencies of behavior to be quickly identified and disseminated to intervention providers, informing the decision-making process [28].

3. Risk and Protective Factors

A public health approach involves developing an understanding of the causes of street gang membership [29]. This takes two forms, with the identification of risk factors (increasing the likelihood of street gang involvement) and protective factors (reducing the likelihood of street gang involvement). By establishing a framework of risk and protective factors, this informs the development of prevention and intervention strategies aimed at reducing involvement in street gangs. To date, focus has been placed on identifying the risk factors for street gang membership, with a paucity of research on the protective factors [30]. This section will outline the risk and protective factors for street gang membership that have been identified.

4. Current Approaches to Street Gang Intervention

Street gang membership has typically been targeted through the criminal justice system, including the imposition of street gang injunctions (behaviors or activities of the street gang member are prohibited, such as going to certain areas [31]. Whilst research has demonstrated reductions in reoffending rates by recipients of street gang injunctions [32], long-term negative effects have also been identified (e.g., reduced opportunities for education and employment, and less access to prosocial networks [33]. However, there has been a recent growth in prevention and intervention programs which are psychologically-informed (e.g., O'Connor and Waddell [34]). These programs have more positive long-term outcomes, for both the individual and the community, than criminal justice approaches [35], and fit well within a public health framework.

5. Good Lives Model as a Public Health Framework

The programs reviewed above represent just a small fraction of the wide range of street gang interventions available. Whilst some interventions are emerging as being effective at preventing or reducing street gang involvement, the vast majority suffer from a weak or limited evidence-base. Critically, there is a lack of consistency in the provision of intervention programs for street gang members across communities. Also, Wood [36] suggests current prevention and intervention strategies are limited by a number of therapeutic issues. Specifically, the benefits of belonging to a street gang (e.g., protection, social and emotional support, sense of identity [37] extend beyond the typical proceeds of crime (i.e., financial and material gain), and are not adequately targeted in interventions. In addition, street gang members' mistrust and lack of motivation frequently hinder intervention efforts [38]. The Good Lives Model (GLM [39]), a novel approach to offender rehabilitation, can provide a framework for street gang interventions which overcomes these obstacles.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

There has been a recent shift from viewing street gangs as a problem for law enforcement to considering street gangs as a priority for public health [40]. The public health approach emphasizes the role of research in understanding the causes of street gang membership, with this informing the development of primary prevention, secondary prevention, and tertiary intervention programs [41]. Whilst research regarding the risk factors for street gang membership has rapidly grown over the past decade, the protective factors preventing involvement are still relatively unknown [30]. As a large number of young people successfully avoid joining street gangs, future research should focus on understanding protective factors which could guide street gang prevention and intervention programs.

A key component of a public health approach involves conducting methodologically sound evaluations of street gang prevention and intervention programs. Whilst this review has demonstrated that some programs are beginning to show promise at reducing street gang involvement (e.g., G.R.E.A.T, FFT-G), the majority of programs lack methodologically sound evaluation (i.e., no control group, reliance on pre-post measures). Furthermore, the use of different definitions of street gang membership across communities has impeded the consistent implementation of prevention and intervention strategies, resulting in mixed findings regarding program effectiveness (e.g., Cure Violence). Thus, to support consistency in the implementation of prevention and intervention programs, it is recommended that the Eurogang definition is used to guide a public health approach to street gangs. Furthermore, in the future, regular evaluations should be embedded into prevention and intervention programs to examine their effectiveness at reducing street gang involvement.

Critically, prevention and intervention programs often suffer from a lack of theoretical foundation and clear goals or objectives [18][17]. This can be overcome by using the GLM framework to guide evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies for street gang members. The GLM assumes that improving an individual's internal skills and external opportunities will support them in attaining their primary goods through prosocial means. If these primary goods are effectively secured, this will reduce the need for young people to engage with a street gang. As the GLM is a model of healthy human functioning [42], it can be utilized across all stages of prevention and intervention. Whilst past research has theoretically applied the GLM to street gang members [43], future research is needed to empirically examine the application of a GLM framework to street gang prevention and intervention programs.

Figure 1. WHO’s public health approach to violence prevention (Krug et al. 2002), adapted for street gang intervention.

2. Surveillance

Surveillance is a core aspect of a public health approach, which informs the development and implementation of prevention and intervention programs (Richards et al. 2017). Surveillance involves establishing clear definitions regarding the population of interest (i.e., street gang members), enabling the identification of both those in need of intervention and the associated risk factors (Department of Health 2012). By implementing surveillance measures, such as analyzing knife crime and criminal convictions data, the extent of the problem in society on a local, national, and international scale can be recognized (World Health Organization 2010). Ongoing monitoring enables any changes in the patterns or frequencies of behavior to be quickly identified and disseminated to intervention providers, informing the decision-making process (Public Health England 2017).

3. Risk and Protective Factors

A public health approach involves developing an understanding of the causes of street gang membership (Local Government Association 2018). This takes two forms, with the identification of risk factors (increasing the likelihood of street gang involvement) and protective factors (reducing the likelihood of street gang involvement). By establishing a framework of risk and protective factors, this informs the development of prevention and intervention strategies aimed at reducing involvement in street gangs. To date, focus has been placed on identifying the risk factors for street gang membership, with a paucity of research on the protective factors (McDaniel 2012). This section will outline the risk and protective factors for street gang membership that have been identified.

4. Current Approaches to Street Gang Intervention

Street gang membership has typically been targeted through the criminal justice system, including the imposition of street gang injunctions (behaviors or activities of the street gang member are prohibited, such as going to certain areas; HM Government 2016). Whilst research has demonstrated reductions in reoffending rates by recipients of street gang injunctions (Carr et al. 2017), long-term negative effects have also been identified (e.g., reduced opportunities for education and employment, and less access to prosocial networks; Swan and Bates 2017). However, there has been a recent growth in prevention and intervention programs which are psychologically-informed (e.g., O’Connor and Waddell 2015). These programs have more positive long-term outcomes, for both the individual and the community, than criminal justice approaches (Howell 2010), and fit well within a public health framework.

5. Good Lives Model as a Public Health Framework

The programs reviewed above represent just a small fraction of the wide range of street gang interventions available. Whilst some interventions are emerging as being effective at preventing or reducing street gang involvement, the vast majority suffer from a weak or limited evidence-base. Critically, there is a lack of consistency in the provision of intervention programs for street gang members across communities. Also, Wood (2019) suggests current prevention and intervention strategies are limited by a number of therapeutic issues. Specifically, the benefits of belonging to a street gang (e.g., protection, social and emotional support, sense of identity; Alleyne and Wood 2010) extend beyond the typical proceeds of crime (i.e., financial and material gain), and are not adequately targeted in interventions. In addition, street gang members’ mistrust and lack of motivation frequently hinder intervention efforts (Di Placido et al. 2006). The Good Lives Model (GLM; Ward and Brown 2004), a novel approach to offender rehabilitation, can provide a framework for street gang interventions which overcomes these obstacles.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

There has been a recent shift from viewing street gangs as a problem for law enforcement to considering street gangs as a priority for public health (Catch22 2013). The public health approach emphasizes the role of research in understanding the causes of street gang membership, with this informing the development of primary prevention, secondary prevention, and tertiary intervention programs (McDaniel et al. 2014). Whilst research regarding the risk factors for street gang membership has rapidly grown over the past decade, the protective factors preventing involvement are still relatively unknown (McDaniel 2012). As a large number of young people successfully avoid joining street gangs, future research should focus on understanding protective factors which could guide street gang prevention and intervention programs.

A key component of a public health approach involves conducting methodologically sound evaluations of street gang prevention and intervention programs. Whilst this review has demonstrated that some programs are beginning to show promise at reducing street gang involvement (e.g., G.R.E.A.T, FFT-G), the majority of programs lack methodologically sound evaluation (i.e., no control group, reliance on pre-post measures). Furthermore, the use of different definitions of street gang membership across communities has impeded the consistent implementation of prevention and intervention strategies, resulting in mixed findings regarding program effectiveness (e.g., Cure Violence). Thus, to support consistency in the implementation of prevention and intervention programs, it is recommended that the Eurogang definition is used to guide a public health approach to street gangs. Furthermore, in the future, regular evaluations should be embedded into prevention and intervention programs to examine their effectiveness at reducing street gang involvement.

Critically, prevention and intervention programs often suffer from a lack of theoretical foundation and clear goals or objectives (Klein and Maxson 2006; McGloin and Decker 2010). This can be overcome by using the GLM framework to guide evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies for street gang members. The GLM assumes that improving an individual’s internal skills and external opportunities will support them in attaining their primary goods through prosocial means. If these primary goods are effectively secured, this will reduce the need for young people to engage with a street gang. As the GLM is a model of healthy human functioning (Purvis et al. 2013), it can be utilized across all stages of prevention and intervention. Whilst past research has theoretically applied the GLM to street gang members (Mallion and Wood 2020b), future research is needed to empirically examine the application of a GLM framework to street gang prevention and intervention programs.