The European Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (EntreComp) offers a comprehensive description of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that people need to develop for an entrepreneurial mindset. Entrepreneurship competencies have usually been equated to management skills, but it is assumed that entrepreneurship activities cannot be narrowed to the management of business, since it requires a wider range of competencies. In particular, the European Council adopted the concept of entrepreneurship competencies as a set of abilities with the potential of shaping society through value creation at a social, cultural, or financial level with the sense of entrepreneurship as one of the eight key competencies necessary for a knowledge-based society.

- entrepreneurial mindset

- entrepreneurial skills

- entrecomp

- self-assessment

- confirmatory factor analysis

1. Introduction

The EntreCompuropean Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (EntreComp) offers a framework of transversal competencies that are applicable to various contexts and allows the promotion of entrepreneurial competencies to face challenges and find solutions in a sustainable way. In this regard, it should be noted that one of the competencies included in the EntreComp framework, in the Ideas and Opportunities dimension, is Ethical and Sustainable Thinking, defined as: assessing the consequences of ideas that bring value and the effect of entrepreneurial action on the target community, the market, society, and the environment. Reflects on how sustainable, long-term social, cultural, and economic goals are, and the course of action chosen. Act responsibly.2. Analysis of Research Results

2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

| Item | Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Mean | SD | Corrected Item-Total Correlation |

Cronbach’s α If Item Deleted |

Subscales (α; Mean: SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|

0.63 | 0.38 | 0.20 | Entrepreneurial intention0.05 | |

| 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.18 | |

| Intrapreneurial Self-Capital | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.48 |

2.4. Reliability

| 1 | 4.91 | 1.11 | 0.65 | 0.78 | Ideas and opportunities (0.83; 26.16; 4.40) |

|||||

|

0.59 | 0.41 | 0.10 | −0.05 | ||||||

| 2 | 5.23 | 1.26 | 0.57 | 0.81 |

|

0.75 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.17 | |

| 3 | 5.41 | 1.14 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

|

0.78 | 0.16 | 0.14 | ||

| 4 | 0.09 | |||||||||

| 5.27 | 1.14 | 0.68 | 0.77 |

|

0.74 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.19 | ||

| 5 | 5.35 | 1.06 | 0.56 | 0.81 |

|

0.47 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.31 | |

| 7 | 5.03 | 1.34 | 0.62 | 0.78 | Personal resources (0.82; 31.18; 5.79) |

|

0.31 | 0.61 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| 5.30 | 1.16 | 0.58 | 0.79 |

|

0.34 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.18 | ||

| 9 | 5.18 | 1.54 | 0.62 | 0.78 |

|

0.18 | ||||

| 10 | 5.45 | 0.73 | 0.15 | 0.13 | ||||||

| 1.32 | 0.55 | 0.80 |

|

0.09 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.22 | |||

|

0.25 | |||||||||

| 11 | 5.39 | 1.16 | 0.59 | 0.79 | 0.51 | 0.29 | ||||

| 17 | 4.83 | 0.28 | ||||||||

| 1.40 | 0.58 | 0.79 |

|

0.07 | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.18 | |||

| 12 | 5.03 | 1.43 | 0.49 | 0.79 | Specific knowledge (0.80; 19.55; 5.68) |

|

0.07 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 0.05 |

| 13 | 3.23 | 1.48 | 0.60 | 0.76 |

|

0.07 | 0.05 | 0.82 | -0.00 | |

|

0.23 | 0.24 | 0.71 | 0.06 | ||||||

|

0.35 | 0.33 |

| |||||||

| 8 | 0.42 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.23 | |||||||

|

0.09 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.07 | ||||||

|

0.03 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.61 | ||||||

|

0.26 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.55 | ||||||

|

0.15 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.73 | ||||||

|

0.14 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.77 |

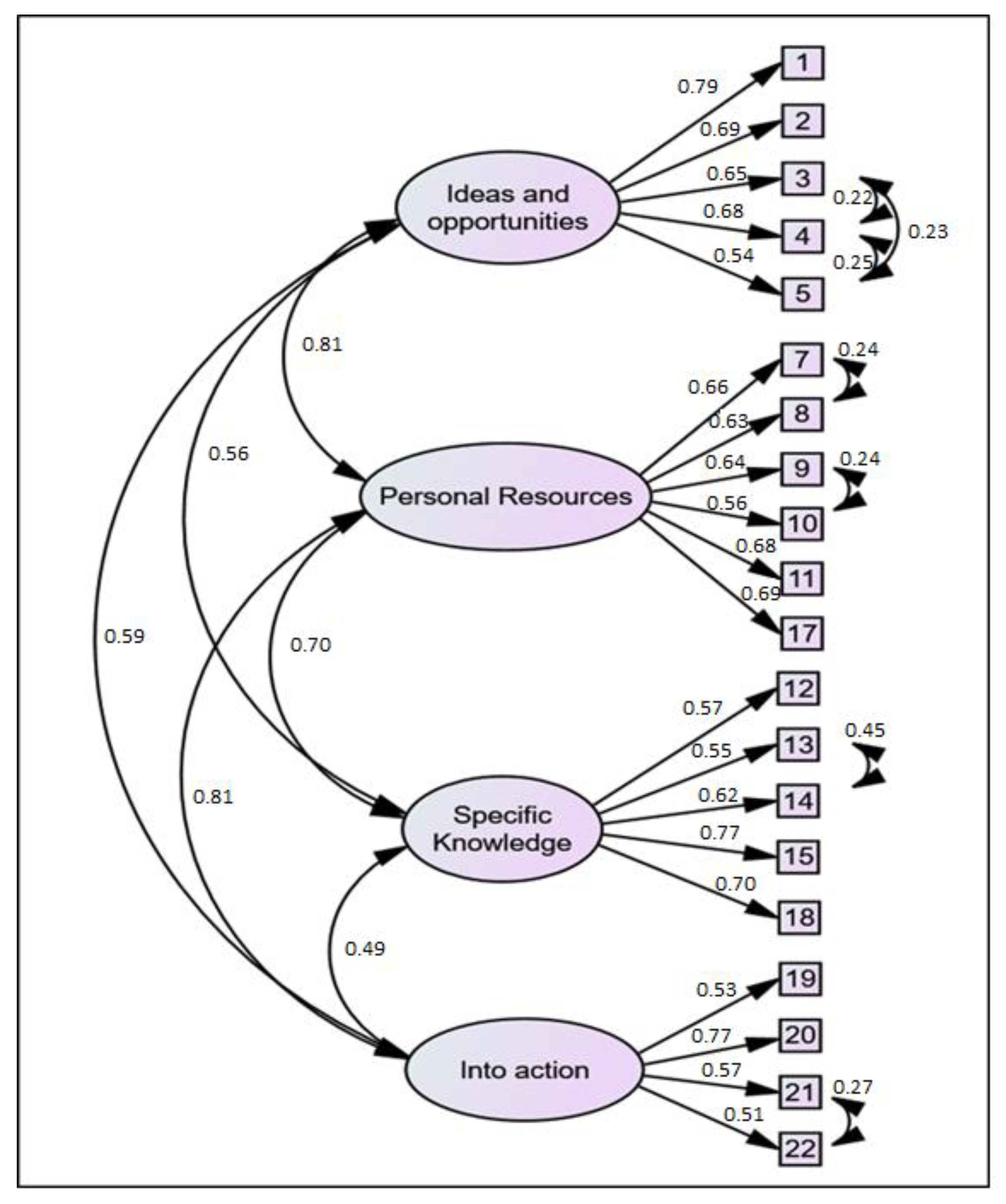

2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

2.3. Evidence of Validity Based on Relationships with Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) and Intrapreneurial Self-Capital (IC)

| R2 | Ideas and Opportunities | Personal Resources | Specific Knowledge | Into Action | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | |||||

| 3.42 | |||||

| 1.58 | |||||

| 0.64 | |||||

| 0.74 | |||||

| 15 | |||||

| 4.05 | 1.48 | 0.63 | 0.74 | ||

| 18 | 3.82 | 1.63 | 0.55 | 0.77 | |

| 19 | 5.87 | 1.14 | 0.46 | 0.69 | Into action (0.72; 23.92; 3.05) |

| 20 | 5.74 | 1.06 | 0.54 | 0.64 | |

| 21 | 6.07 | 0.99 | 0.52 | 0.65 | |

| 22 | 6.25 | 0.93 | 0.52 | 0.65 |

3. Current Insights

References

- Markman, G.D.; Baron, R.A.; Balkin, D.B. Are perseverance and self-efficacy costless? Assessing entrepreneurs’ regretful thinking. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 1–19.

- Armuña, C.; Ramos, S.; Juan, J.; Feijóo, C.; Arenal, A. From stand-up to start-up: Exploring entrepreneurship competences and STEM women’s intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 69–92.

- Bacigalupo, M.; Kampylis, P.; Punie, Y.; Van den Brande, G. EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework. In European Commission Scientific and Technical Research Reports; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016.

- European Commission. Rethinking Education: Investing in Skills for Better Socio-Economic Outcomes. 2012. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/com669_en.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- European Commission. A New Skills Agenda for Europe. Working Together to Strengthen Human Capital, Employability and Competitiveness. Com (2016)381/F1. 2016. Available online: https://community.oecd.org/docs/DOC-131502 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Lackéus, M. Entrepreneurship in Education: What, Why, When How. Background paper for OECD-LEED. 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/BGP_Entrepreneurship-in-Education.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Wilson, K.; Vyakarnam, S.; Volkmann, C.; Mariotti, S.; Rabuzzi, D. Educating the Next Wave of Entrepreneurs: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Capabilities to Meet the Global Challenges of the 21st Century. In World Economic Forum: A Report of the Global Education Initiative; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- McCallum, E.; Weicht, R.; McMullan, L.; Price, A.; Bacigalupo, M.; O’Keeffe, W. EntreComp into Action: Get inspired, make it happen. In European Commission Scientific and Technical Research Reports; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018.

- Bacigalupo, M.; Weikert García, L.; Mansoori, Y.; O’Keeffe, W. EntreComp Playbook. Entrepreneurial Learning beyond the Classroom; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Lackéus, M.; Lundqvist, M.; Middleton, K.W.; Inden, J. The Entrepreneurial Employee in the Public and Private Sector—What, Why, How; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020.

- EntreComp Europe. Inspiring Practices from across Europe 2020. Available online: https://entrecompeurop.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/EntreComp_Europe_Inspiring_Practices.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Bandura, A. Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In Handbook of Principles of Organization Behavior, 2nd ed.; Locke, E.A., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 179–200.

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 240–261.

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 82–91.

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419.

- López-Núñez, M.I.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; Aparicio-García, M.E.; Díaz-Ramiro, E.M. Are entrepreneurs born or made? The influence of personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 154, 109699.

- McMullen, J.S.; Ingram, K.M.; Adams, J. What makes an entrepreneurship study entrepreneurial? Toward a unified theory of entrepreneurial agency. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 1197–1238.

- Badoer, E.; Hollings, Y.; Chester, A. Professional networking for undergraduate students: A scaffolded approach. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 197–210.

- Batistic, S.; Tymon, A. Networking behaviour, graduate employability: A social capital perspective. Educ. Train. 2017, 388.

- Bhatti, M.A.; Al Doghan, M.A.; Saat, S.A.M.; Juhari, A.S.; Alshagawi, M. Entrepreneurial intentions among women: Does entrepreneurial training and education matters? (Pre-and post-evaluation of psychological attributes and its effects on entrepreneurial intention). J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2021, 28, 167–184.

- Di Fabio, A.; Gori, A. Developing a new instrument for assessing acceptance of change. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 802.

- Rodrigues, R.; Butler, C.L.; Guest, D. Antecedents of protean and boundaryless career orientations: The role of core self-evaluations, perceived employability and social capital. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 1–11.

- Mitchelmore, S.; Rowley, J. Entrepreneurial Competencies of Women Entrepreneurs Pursuing Business Growth. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2013, 20, 125–142.

- Bacigalupo, M.; Kampylis, P.; McCallum, E.; Punie, Y. Promoting the Entrepreneurship Competence of Young Adults in Europe: Towards a Self-Assessment Tool. In Proceedings of the ICERI, Sevilla, Spain, 14–16 November 2016.