Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Vengadesh Periasamy.

The prevalence of photosynthesis, as the major natural solar energy transduction mechanism or biophotovoltaics (BPV), has always intrigued mankind. The development of high performance and durable BPVs is dependent on upgraded anode materials with electrochemically dynamic nanostructures. However, the current challenges in the optimization of anode materials remain significant barriers towards the development of commercially viable technology. Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) film has been substantiated as an efficacious film-forming technique to tackle the above limitations of algal BPVs; however, the aforesaid technology remains vastly untapped in BPVs.

- Langmuir–Blodgett

- graphene

- Biophotovoltaics

- Fuel Cells

1. Fundamentals of the LB Technique and Its Applications for Graphene-Based Films

The LB technique is a popular method due to its innate ability to produce large areas of highly uniform thin films, in addition to allowing the re-engineering and manipulation of structures on nano- and microscales [11,34,37][1][2][3] to produce films of different density and packing and with different arrangements of physical properties [38][4]. In addition, the LB technique does not involve extreme working conditions, such as high temperature and pressure or release of harmful and toxic chemicals, making it an inexpensive and environmentally friendly technique.

GO is generally preferred for producing LB films compared to graphene due to its natural amphiphilic properties [39][5]. The hydrophobic domain of GO is attributed to the π–π conjugated sp2 carbon, while the O group binding with the basal plane confers hydrophilic properties [40][6]. GO has low diffusivity in water, which is attributed to the ionizable edge of the -COOH group. It is in this regard that GO has been considered as an amphiphile with a largely hydrophobic basal plane and hydrophilic edge. Some amounts of GO do dissolve into the subphase; however, larger sheets typically float on the water surface while smaller ones might sink due to the increase in hydrophilicity, as reported by J. Kim et al. [39][5]. This amphiphilic property results in the formation of a stable water-insoluble monolayer, a prerequisite for a material to be used in LB assembly. A further reduction process yields rGO, which effectively reduces the hydrophilicity of the material. To obtain 2D rGO films, the synthesized rGO should be diluted with methanol, a polar alcohol, since rGO has the tendency to collapse and form 3D structures in the presence of non-polar solvents [41][7].

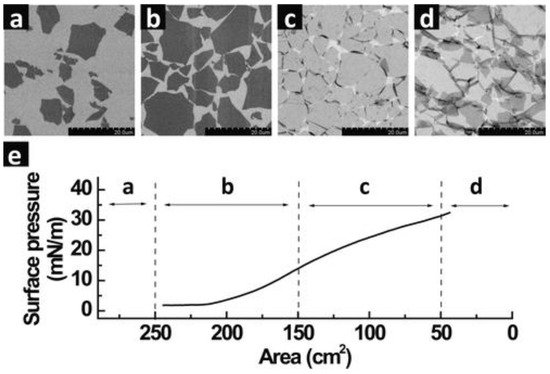

An isotherm graph, which is typically a surface pressure versus area profile, generated upon compression of the GO monolayer on top of the water subphase is monitored using a tensiometer (Figure 21). The slope or the gradient of the isotherm defines the characteristics of the monolayer such that an increasing gradient demonstrates a state of increasingly reactive amphiphilic monolayer elements, while a decreasing value represents a state of collapse in which the elements leave the air/water interface. Barrier speed is set at the lowest possible speed, commonly around 7–10 mm/min or lower, to enable homogeneous and uniform monolayer compression. As the barriers start to compress the monolayer, a region of gaseous state can be observed (a) indicating the formation of individually isolated GO sheets as a result of well-dispersed sheets on the water subphase. At this stage, the surface pressure remains constant. Even though the region is a coexistence between isolated GO sheets and some of the sheets interacting with each other, the phase defined is merely the representation or the association of the surface pressure versus area. The physical properties of liquid and gases at microscopic dimensions are isotropic by narure, therefore they are not direction-dependent. Liquids and gases are therefore similar under certain conditions (in the case of GO spreading on a water surface) making it non-trivial to differentiate between these two states. As such, the 2D monolayer phase is generally defined as the condition in which molecules spread far apart on the surface exert significantly smaller forces on one another [31][8]. Upon continuous compression, the GO sheets come into contact with each other (b), increasing the surface pressure significantly as a result of the electrostatic repulsion of the individual GO sheets upon achieving a close-packed arrangement. Further compression of the barrier causes the surface pressure to continuously rise, albeit the gradient is lower (c) than the previous region in (b). At this stage, the monolayer goes beyond a close-packed arrangement and folding of the GO sheet appears at the interconnected edges.

Figure 21. The LB assembly of single monolayers of GO on top of a silicon wafer with different regions of compression area: (a) dilute monolayers of isolated GO sheets, (b) close-packed arrangement, (c) over-packed monolayers with a folded sheet at interconnecting edges and (d) over-packed monolayers with folded and partially overlapped GO sheets interlocking with each other. (e) Isothermal surface pressure versus subphase (water) area plotted for the corresponding regions of (a–d). Scale bar is 20 µm. Reprinted with permission from the Journal of the American Chemical Society, copyright 2009, American Chemical Society [37][3].

The monolayer is inclined to disrupt into multilayers around the edges due to the flexibility of the soft edges of the GO sheet. However, the central area of the GO sheet in general remains flat without much wrinkling or folding. The folding effect at the edge of the GO may be described by the effect of the slightly lower gradient of the isotherm graph representing the region in (c). Continuous compression finally pushes the LB film to breaking point at which the GO sheets start to buckle, wrinkle, overlap and/or partially overlap [42][9]. Smaller GO sheets seem to completely crumble while larger sheets maintain flatness in the center. This is due to the edge-to-edge interactions of the GO sheets on the water subphase during the compression process. The center of the GO sheet maintains flatness, while the edges buckle, wrinkle, overlap and/or partially overlap, as mentioned earlier due to the repulsion at the edges. The GO sheet at the center of the subphase will, however, remain flat until it reaches the point where no more free space is left upon further continuous compression [37][3].

The final step in the formation of 2D graphene-based film is the transfer and deposition of the GO layer or film onto a solid substrate using the dipping process. This method, however, proves challenging for producing thin films of large area [43,44][10][11]. Hence, numerous methods have been developed, especially to improve the deposition of rGO and GO films onto solid substrates. These includes using hydrophobic substrates [45][12], a roll-to-roll deposition process [46][13], controlled edge-to-edge assembly of floating films [43][10] and guided transfer by adjusting the substrate to a shallow angle [44][11]. Cote and co-workers determined the optimum gap size of the GO sheet at each stage of arrangement by dipping solid substrates at various surface pressures representing close-packed to nearly over-packed arrangements [37][3]. The resulting surface morphology of the GO layers was then analyzed using atomic force microscopy (AFM). Variation in gap sizes was observed for each arrangement of GO sheets, even at over-packed stages where nanogaps were observed due to electrostatic repulsion between the sheets.

2. Graphene-Based LB Films for Fuel Cell Applications

Traditional and manipulated LB deposition methods have been reported to yield high-quality and large 2D rGO or GO thin films. The traditional method involves vertical dipping of the substrate through a water subphase during the close-packing arrangement of rGO sheets [37][3]. For efficient material adhesion and for effective draining of water, a vertical dipping process could be carried out at a very low speed to increase adhesion time, as rGO will not attach well to the substrate at high dipping speeds [34][2]. The resulting 2D rGO thin film is then air-dried at room temperature or kept in an oven to enhance the drying process [18][14].

The traditional method can be manipulated in several ways to deposit large-area 2D GO films. Xu and co-workers demonstrated a controlled edge-to-edge assembly of a floating 2D GO monolayer with the ability to yield large-area films [43][10]. The method includes an improved spreading of solvent using ethanol/1, 2-dichloroethane with a volume ratio of 1:13 instead of the traditional methanol/water (ratio 5:1). As a result, the transfer efficiency increased by five-fold and a large accumulation of GO monolayer was achieved.

The mechanism of controlled edge-to-edge assembly contributes to barrier-free densification, the aggregation mechanism and spreading-induced film. The barrier-free densification of the LB film is accomplished by using repetitive dripping deposition of 0.025 mg/mL GO dispersion at the air–water interface. This method proves to be nearly 100% efficient in transferring a GO monolayer onto a large-area substrate at the air–water interface and is attributed to the immersion forces that occur while the spreading solvent evaporates. The aggregation mechanism is carried out by depositing GO dispersion at a low pH onto a highly ionic subphase, which results in the shielding of repulsive electrostatic forces between individual GO sheets. Spreading-induced film densification is achieved by spreading solvent at a suitable distance-dependent force from floating GO films. Compression of barriers will then effectively assist to form a densely tiled film. The distance-dependent force is transmitted throughout the LB trough dissimilarly depending on whether the interaction between the sheets is governed by repulsive or attractive forces.

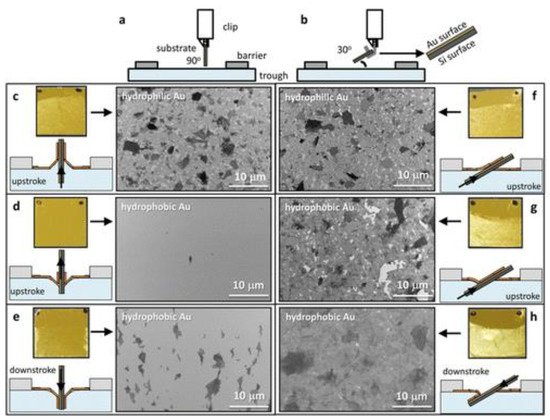

Using this mechanism, a continuous deposition of 2D GO film onto a large-area substrate for coating and patterning using roll-to-roll deposition was achieved [43][10]. In another report, the quality of the 2D films was significantly improved by manipulating the monolayer transfer process by adjusting the solid substrate at a slight angle during the dipping [44][11]. This observed improvement was due to the beneficiation of shear modulus causing GO to behave like a 2D substrate on the water subphase as a result of the strong interaction of each individual GO sheet at the air–water interface. Furthermore, the implementation of a shallow-angled substrate during the dipping process projects a minimum tensile stress during the insertion and extraction of the substrate (Figure 32). Poor GO adhesion onto hydrophobic surfaces resulting in low-quality film formation or coating when using a conventional vertical dipping method can be overcome by adjusting the dipping angle of the substrate to 30°, which creates a desirable meniscus radius of curvature.

Figure 32. A comparison of conventional (a) 90° and (b) 30° dipping mechanisms of upstroke and downstroke of different hydrophobic and hydrophilic substrates. The SEM images show the comparison of the GO film formations in the upstroke (c,f) hydrophilic and (d,g) hydrophobic substrates of Au at both 90° and 30°. (e,h) SEM film formations as a result of downstroke using a hydrophobic Au substrate. Reprinted with permission from the Journal of the American Chemical Society, copyright 2015, American Chemical Society [44][11].

Three-dimensional graphene-based materials, meanwhile, are of particular interest due to their intrinsic properties similar to 2D graphene sheets while they also have the added benefits of increased surface areas combining meso-, macro- and micropores. The meso- and microporosity display a highly specific area and macroporosity significantly improves the catalytic performance at the surface region [47][15]. These 3D porous structures coupled with the intrinsic properties of graphene impart high specific surface areas, durable mechanical strength and fast mass and electron transport kinetics. In line with this, several non-LB techniques have been developed to fabricate 3D structures. These include step-by-step assembly methods using graphene, GO or rGO sheets and direct synthesis from a carbon source (methane, ethanol or sugar) [34,48,49][2][16][17].

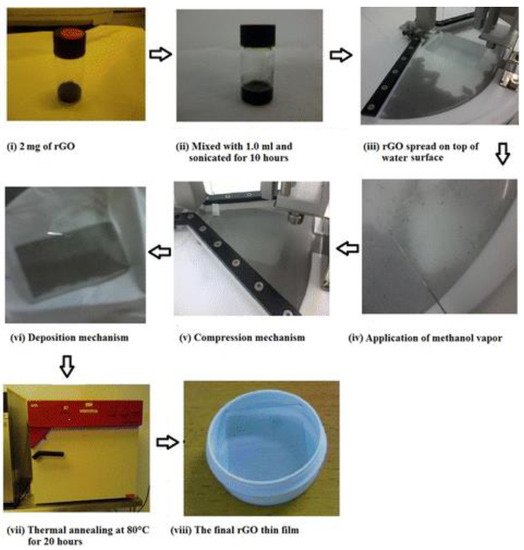

In a recent report, an unconventional approach was employed using the LB method for preparing 3D rGO films [34][2]. While dipping is conventionally carried out at the solid-state target pressure for preparing 2D LB film (Figure 43), Jaafar and co-workers carried out the deposition beyond the target pressure up to the breaking point. Beyond the breaking point, collapse or breakdown in the arrangement of the monolayer results in the formation of multilayers, providing an overall 3D morphology. Wrinkling effects are predominant while electrostatic repulsion between the 2D layers increases the average thickness [42][9]. Moreover, this may also increase the average roughness when the sheets crumble and wrinkle unevenly at different areas. Repeated transfer or layer-by-layer deposition further improves the 3D structures.

Figure 43. Flowchart showing the preparation of rGO LB film. To distribute the rGO flakes evenly, methanol vapor from a methanol-soaked tissue was applied to gently force the clouded regions apart to significantly improve the film uniformity. Reprinted with permission from ACS Publications, copyright 2015, American Chemical Society [34][2].

Annealing at 60 °C between each consecutive deposition of layers helps to create higher surface roughness and improves the porosity of the 3D structures. It was reported that at the sixth deposition layer of rGO, complex interconnected micrometer-scale porous structures were achieved which enabled enhanced integration and encapsulation of microalgae within BPV FCs for increased power output [36][18]. At higher deposition cycles, the roughness and pore size were increased, thus adjustment of the deposition cycles could be a useful way of achieving various roughness and pore sizes of 3D structures. These tunable properties may play important roles in cellular interactions by influencing cell behavior in biological microenvironments, such as in the rGO biofilms [50,51,52,53,54,55][19][20][21][22][23][24]. Compared to 2D graphene-based films, 3D structures provide excellent cellular communication, transportation of oxygen and nutrients, removal of waste and improved cellular metabolism. Furthermore, high porosity allows significant improvement in the adhesion of biomaterials and, in the case of microalgae, allows enhanced growth. As such, the LB technique provides a practical solution for controlling and optimizing surface roughness and pore size with respect to its intended applications.

References

- Zheng, Q.; Shi, L.; Yang, J. Langmuir-Blodgett assembly of ultra-large graphene oxide films for transparent electrodes. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 2504.

- Jaafar, M.M.; Ciniciato, G.P.M.K.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Phang, S.M.; Yunus, K.; Fisher, A.C.; Iwamoto, M.; Periasamy, V. Preparation of a Three-Dimensional Reduced Graphene Oxide Film by Using the Langmuir–Blodgett Method. Langmuir 2015, 31, 10426.

- Cote, L.J.; Kim, F.; Huang, J. Langmuir−Blodgett Assembly of Graphite Oxide Single Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1043–1049.

- Velázquez, M.M.; Alejo, T.; López-Díaz, D.; Martín-García, B.; Merchán, M.D. Two-Dimensional Materials—Synthesis, Characterization and Potential Applications; In TechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2016.

- Kim, J.; Cote, L.J.; Huang, J. Two Dimensional Soft Material: New Faces of Graphene Oxide. Acc.Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1356.

- Lerf, A.; He, H.; Forster, M.; Klinowski, J. Structure of Graphite Oxide Revisited. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 4477.

- Wen, X.; Garland, C.W.; Hwa, T.; Kardar, M.; Kokufuta, E.; Li, Y.; Orkisz, M.; Tanaka, T. Crumpled and collapsed conformations in graphite oxide membranes. Nature 1992, 355, 426.

- Petty, M.C. Langmuir-Blodgett Films: An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996.

- Zheng, Q.; Shi, L.; Ma, P.C.; Xue, Q.; Li, J.; Tang, Z.; Yang, J. Structure control of ultra-large graphene oxide sheets by the Langmuir–Blodgett method. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 4680.

- Xu, L.; Tetreault, A.R.; Khaligh, H.H.; Goldthorpe, I.A.; Wettig, S.D.; Pope, M.A. Continuous Langmuir–Blodgett Deposition and Transfer by Controlled Edge-to-Edge Assembly of Floating 2D Materials. Langmuir 2019, 35, 51.

- Harrison, K.L.; Biedermann, L.B.; Zavadil, K.R. Mechanical Properties of Water-Assembled Graphene Oxide Langmuir Monolayers: Guiding Controlled Transfer. Langmuir 2015, 31, 9825–9832.

- Kouloumpis, A.; Thomou, E.; Chalmpes, N.; Dimos, K.; Spyrou, K.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Koutselas, I.; Gournis, D.; Rudolf, P. Graphene/Carbon Dot Hybrid Thin Films Prepared by a Modified Langmuir–Schaefer Method. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2090.

- Bae, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.; Xu, X.; Park, J.S.; Zheng, Y.; Balakrishnan, J.; Lei, T.; Kim, H.R.; Song, Y.I.; et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent électrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 574.

- Zheng, Q.; Ip, W.H.; Lin, X.; Yousefi, N.; Yeung, K.K.; Li, Z.; Kim, J.-K. Transparent Conductive Films Consisting of Ultralarge Graphene Sheets Produced by Langmuir–Blodgett Assembly. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6039.

- Qiu, B.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. Recent advances in three-dimensional graphene based materials for catalysis applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2165.

- Chen, Z.; Ren, W.; Gao, L.; Liu, B.; Pei, S.; Cheng, H.M. Three-dimensional flexible and conductive interconnected graphene networks grown by chemical vapour deposition. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 424.

- Ma, Y.; Chen, Y. Three-dimensional graphene networks: Synthesis, properties and applications. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2015, 2, 40.

- Ng, F.L.; Jaafar, M.M.; Phang, S.M.; Chan, Z.; Salleh, N.A.; Azmi, S.Z.; Yunus, K.; Fisher, A.C.; Periasamy, V. Reduced Graphene Oxide Anodes for Potential Application in Algae Biophotovoltaic Platforms. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7562.

- Singhvi, R.; Stephanopoulos, G.; Wang, D.I.C. Effects of substratum morphology on cell physiology. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1994, 43, 764.

- Brauker, J.H.; Carr-Brendel, V.E.; Martinson, L.A.; Crudele, J.; Johnston, W.D.; Johnson, R.C. Neovascularization of synthetic membranes directed by membrane microarchitecture. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1995, 29, 1517.

- Bobyn, J.D.; Wilson, G.J.; MacGregor, D.C.; Pilliar, R.M.; Weatherly, G.C. Effect of pore size on the peel strength of attachment of fibrous tissue to porous-surfaced implants. J. Biomed. Mat. Res. 1982, 16, 571.

- Clark, P.; Connolly, P.; Curtis, A.S.; Dow, J.A.; Wilkinson, C.D. Topographical control of cell behaviour. I. Simple step cues. Development 1990, 108, 635.

- Rosengren, A.; Bjursten, L.M.; Danielsen, N.; Persson, H.; Kober, M.J. Tissue reactions to polyethylene implants with different surface topography. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1999, 10, 75.

- Flemming, R.G.; Murphy, C.J.; Abrams, G.A.; Goodman, S.L.; Nealey, P.F. Effects of synthetic micro- and nano-structured surfaces on cell behavior. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 573.

More