Telogen effluvium is a scalp disorder characterized by diffuse, non-scarring hair shedding. The term “telogen effluvium” (TE) was proposed to differentiate the disorder from the excessive shedding of normal club hair. It affects both males and females, with a higher incidence rate in females. Various hypotheses have been proposed for the pathophysiology of TE, based on abnormalities in the normal hair cycle, triggered by different factors.

- SARS-CoV-2

- COVID-19

- telogen effluvium

- alopecia

1. Introduction

2. Detailed Analysis

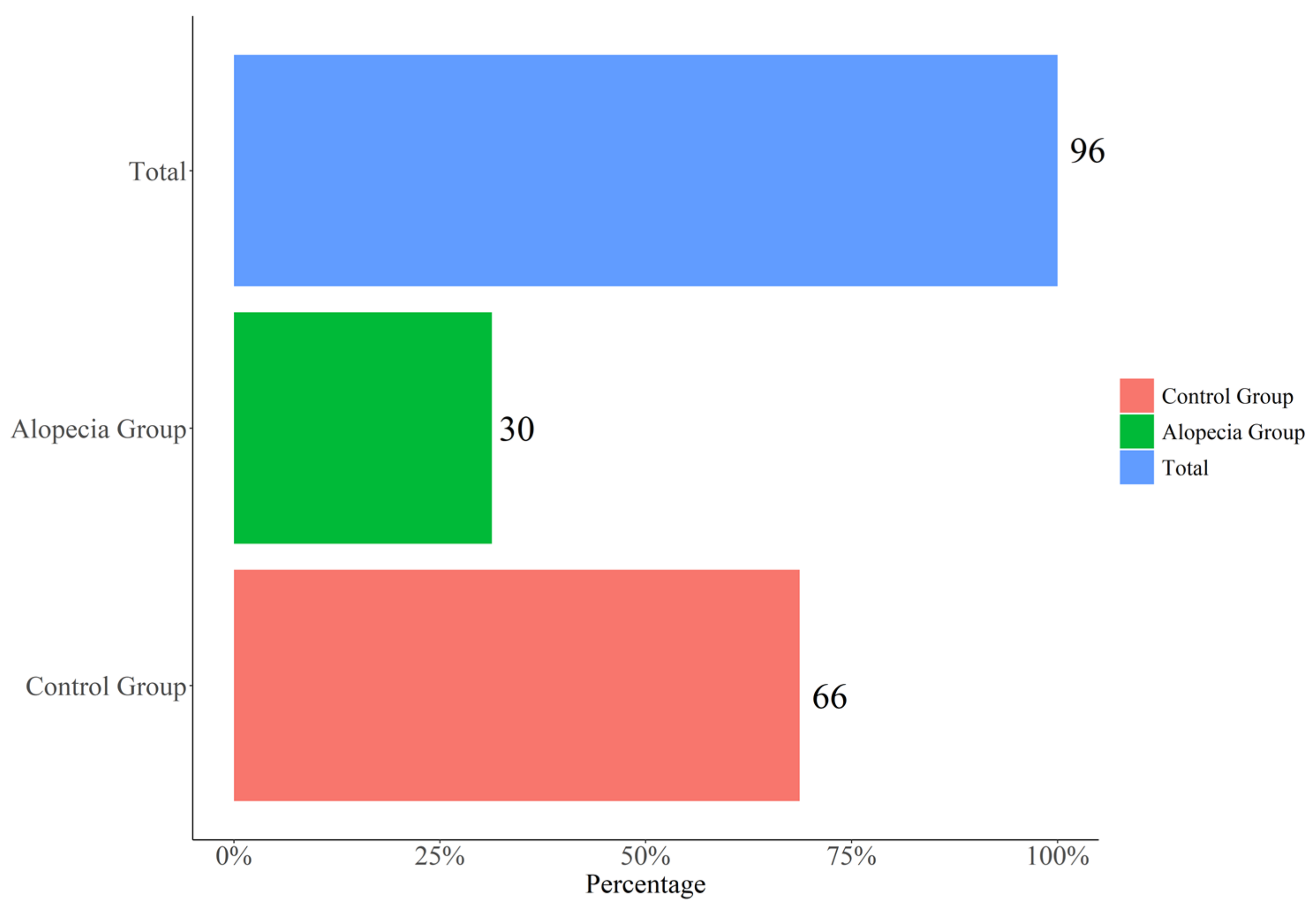

2.1. Characteristics of Participants

| Variable | OVERALLN = 96 | No-Alopecia n = 66 | Alopecia n = 30 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: | <0.001 | |||

| F | 34 (35.4%) | 12 (18.2%) | 22 (73.3%) | |

| M | 62 (64.6%) | 54 (81.8%) | 8 (26.7%) | |

| Age (years) | 59.0 (54.5-65.0) | 59.0 (55.2;64.8) | 59.0 (53.2;66.5) | 0.880 |

| Swab positivity(days) | 31.0 (26.0-37.0) | 31.0 (26.0;37.0) | 29.5 (25.2;34.5) | 0.274 |

| Hospitalization (days) | 13.0 (9.0-16.5) | 14.0 (8.25;17.0) | 11.5 (10.0;15.0) | 0.444 |

| Fever (days) | 11.0 (9.0-13.0) | 10.5 (8.25;13.0) | 11.0 (9.25;14.8) | 0.225 |

| DRUG | ||||

| Lopinavir: | 0.611 | |||

| No | 72 (75.0%) | 48 (72.7%) | 24 (80.0%) | |

| Yes | 24 (25.0%) | 18 (27.3%) | 6 (20.0%) | |

| Darunavir: | 0.330 | |||

| No | 12 (12.5%) | 10 (15.2%) | 2 (6.67%) | |

| Yes | 84 (87.5%) | 56 (84.8%) | 28 (93.3%) | |

| Ritonavir: | 0.847 | |||

| No | 2 (2.1%) | 2 (3.03%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Yes | 94 (97.9%) | 64 (97.0%) | 30 (100%) | |

| Chloroquine: | 0.778 | |||

| No | 13 (13.5%) | 9 (13.6%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| Yes | 83 (86.5%) | 57 (86.4%) | 26 (86.7%) | |

| Azithromycine: | 0.977 | |||

| No | 37 (38.5%) | 25 (37.9 | 12 (40.0%) | |

| Yes | 59 (61.5%) | 41 (62.1%) | 18 (60.0%) | |

| O2: | 0.233 | |||

| No | 23 (24.0%) | 13 (19.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | |

| Yes | 73 (76.0%) | 53 (80.3%) | 20 (66.7%) | |

| Steroids: | 0.611 | |||

| No | 72 (75.0%) | 48 (72.7%) | 24 (80.0%) | |

| Yes | 24 (25.0%) | 18 (27.3%) | 6 (20.0%) | |

| Pulmonary Embolism prophylaxis: | 0.049 | |||

| No | 65 (67.7%) | 40 (60.6%) | 25 (83.3%) | |

| Yes | 31 (32.3%) | 26 (39.4%) | 5 (16.7%) |

2.2. Post-COVID Alopecia Characteristics

2.3. COVID-19 Characteristics and Alopecia

2.4. Laboratory and Alopecia

3. Current Insights

The rate of post-SARS-CoV2 TE appeared to be significantly higher in females, although in males the onset of alopecia was more premature. This occurrence could be linked to the evidence that men infected with CoV-2 have an increased risk of severe COVID-19 disease compared to women [24][4]. A large number of other factors have been associated with this gender disparity. There is evidence that supports the role of androgens in the COVID-19 severity [25[5][6],26], to the extent that androgenic alopecia has been hypothesized as a predicting factor for more severe SARS-CoV-2 cases [27][7]. In the research, TE is not reported as a causative factor, but as the consequence of the disease. Physiological stress, such as childbirth, surgical trauma, high fever, chronic systemic illness or infections, and hemorrhage have been associated with TE. However, the relationship between TE and emotional stress is uncertain and ambiguous [23][8]. TE has also been linked to severe protein, fatty acid and zinc deficiency, chronic starvation, and caloric restriction [23][8]. Numerous drugs can cause TE, starting after Week 12 of dosage [11,28][9][10]. Iatrogenic causes of TE include oral contraceptive pills, androgens, retinoids, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and anticoagulants (heparin) [29][11]. The relation between TE and anticoagulant therapy is strongly controversial in the literature [19][12]; however, no association was manifest here. The onset of hair loss in the sample started just over 2 months from the beginning of the fever but, at the same time, it showed no link with any significant laboratory abnormalities. In particular, zinc and iron deficiencies were not related to the onset of alopecia. In the context of these considerations, ATE following SARS-CoV infection is to be considered as a foreseeable complication directly related to the disease. The report on the absence of any association with the severity of infection and treatments has major implications on the number of patients potentially affected. The absence of a nutritional deficiency, combined with trichodynia, may suggest that the inflammatory condition inherent to COVID-19 may be a principal cause of ATE. Interestingly, the prevalence of trichodynia—a distinctive symptom of TE—is reported in only about 20% of TE patients [30][13], whereas in this sample, it affected almost one-quarter of subjects.

References

- Malik, Y.S.; Sircar, S.; Bhat, S.; Vinodhkumar, O.R.; Tiwari, R.; Sah, R.; Rabaan, A.A.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Dhama, K. Emerging coronavirus disease (COVID-19), a pandemic public health emergency with animal linkages: Current status update. Preprints 2020, 2020030343.

- COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic, 10 June. Worldometers.Info. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdvegas1 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Li, L.; Li, R.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, J.; Chen, D. Therapeutic strategies for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 45.

- Gebhard, C.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Neuhauser, H.K.; Morgan, R.; Klein, S.L. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 29.

- Wambier, C.G.; Vaño-Galván, S.; McCoy, J.; Gomez-Zubiaur, A.; Herrera, S.; Hermosa-Gelbard, Á.; Moreno-Arrones, O.M.; Jiménez-Gómez, N.; González-Cantero, A.; Fonda-Pascual, P. Segurado-Miravalles, G. Androgenetic alopecia present in the majority of patients hospitalized with COVID-19: The “Gabrin sign”. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 680–682.

- Montopoli, M.; Zumerle, S.; Vettor, R.; Rugge, M.; Zorzi, M.; Catapano, C.V.; Carbone, G.M.; Cavalli, A.; Pagano, F.; Ragazzi, E.; et al. Androgen-deprivation therapies for prostate cancer and risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2: A population-based study (N = 4532). Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1040–1045.

- Asghar, F.; Shamim, N.; Farooque, U.; Sheikh, H.; Aqeel, R. Telogen Effluvium: A Review of the Literature. Cureus 2020, 12, e8320.

- Almagro, M.; del Pozo, J.; Garcia-Silva, J.; Castro, A.; López-Calvo, S.; Yebra-Pimentel, M.T.; Fonseca, E. Telogen effluvium as a clinical presentation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am. J. Med. 2002, 112, 508–509.

- Rebora, A. Proposing a Simpler Classification of Telogen Effluvium. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016, 2, 35–38.

- Tosti, A.; Pazzaglia, M. Drug reactions affecting hair: Diagnosis. Dermatol. Clin. 2007, 25, 223–231.

- Harrison, S.; Bergfeld, W. Diffuse hair loss: Its triggers and management. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2009, 76, 361–367.

- Watras, M.M.; Patel, J.P.; Arya, R. Traditional anticoagulants and hair loss: A role for direct oral anticoagulants? A review of the literature. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2016, 3, 1–6.

- Sulzberger, M.B.; Witten, V.H.; Kopf, A.W. Diffuse alopecia in women. Its unexplained apparent increase in incidence. Arch Dermatol. 1960, 81, 556–560.