Ultrasonication is a valuable technique and has diverse applications in food items, such as mechanical cell distortions in order to enhance the retrieval of bioactive components, micro-organism inactivation and immiscible liquid emulsification

[31][42][43][15,101,102]. Recently, low frequency (16–100 kHz), high frequency (HIU, 10–1000 Wcm

−2) ultrasonic techniques have been developed as a fast and secure application to alter protein structures, functional and physicochemical properties

[44][103]. Most importantly, ultrasonication is widely encouraged by researchers to enhance food quality. Ultrasonic techniques have special characteristics that make them more effective, such as microstreaming currents, turbulence, high pressure, cavitation bubbling, leading to modification of protein structural properties

[45][104]. Gülseren, et al.

[46][105] reported that adding phenolic compounds to proteins and treating them with ultrasonic techniques could reduce protein cross-linking and oxidation, both of which play important roles in the gelling and textural properties of seafood proteins. He, et al.

[47][106] reported that the application of ultrasonication combined with high salt concentration enhanced the textural properties (hardness and springiness) of silver carp surimi. Meanwhile, it prevented the change in secondary structural changes by inhibiting the unfolding of α-helix content. Pan, et al.

[48][107] reported that the addition of phenolic compounds to MPs and treatment with ultrasonication reduced the protein oxidation (surface hydrophobicity and carbonyls) by enhancing the hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions. A big rise in the yield of soy protein isolate (SPI) catalyzed by mTGases led to an improvement in WHC and textural properties after the ultrasonication technique. Therefore, ultrasonication is also helpful in raising the SPI and wheat gluten-based hydrogels by assisting in protein structural modifications

[49][108]. Xu, Lv, Zhao, He, Li, Yi and Li

[45][104] reported that the ultrasound treatment with diacylglycerol (DAG) enhanced the gelling attributes of golden thread surimi. In addition, ultrasound combined with (DAG) improved the structural and microstructural properties of golden thread surimi by enhancing the intermolecular interaction, hydrogen and hydrophilic bindings. The use of short-term sonication speeds up water leakage rates because of the existence of poor structural matrix protein gels

[50][109]. In addition, the production of low-porosity, homogenous protein structures for water absorption at higher sonic times can be related to two distinct mechanisms, including: (I) an exposition through modifications in the molecular conformation of proteins to internal active polar groups on the surface and (ii) a more fitting dispersion of these functionary groups into a sonic reaction environment

[44][103]. It has previously been observed that high-intensity ultrasonic treatment could enhance the gel strength of SPI-set gels caused by adding glucono-β-lactone

[51][110] and calcium sulfate

[52][111]. Gao, et al.

[53][112] reported that the polysaccharide-added surimi protein had higher Ca2

+ATPase and sulfhydryl content after ultrasonication, which reduced oxidative changes in the myosin globular head by stimulating hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions. Thus, this results in a more stable gel texture and structure. Ultrasonic application appears to alter the function of the protein matrix by expanding the amount of interfacial covalent interactions. Typically, hydrophobic associations in the protein gel matrix are intensified following ultrasonication

[51][110]. Hu, et al.

[54][113] have demonstrated that the secondary SPI textural properties of mTGase-based gels were not altered at 20 kHz and 400 W of ultrasonic treatment. However, Gharibzahedi, Roohinejad, George, Barba, Greiner, Barbosa-Cánovas and Mallikarjunan

[26][13] reported modifications of the secondary structure of the wheat gluten-SPI gels caused by ultrasonic technique, leading to increased β-sheets, decreased α-helices and β-turns, which indicates fewer protein oxidative, denaturation and aggregation changes. Cui, et al.

[55][114] have identified an increase in β sheet count to boost the hydrophobic surface and viscoelastic properties of protein gels. The enhanced configurations of the β-sheets also modified the protein-protein cross-linking of hydrophobic active groups. β-sheets are more capable of hydrating water molecules compared to α-helix during ultrasonic pretreatment and it provides stronger hydrogels

[54][113]. Ultrasonication can transform the molecular protein structure from β-turns into random coils in order to improve the cross-linkage of amino acid side chains

[31][15]. Therefore, the larger amount of inter-molecular disulfide bonds in ultrasonic-based surimi gels can also justify the rise in gel strength. The appearance of a polymer matrix with more compact and dense aggregations of multi-molecular cross-links, hydrophobic associations and inter-molecular disulfide bindings, increases the gel strength

[56][115]. The microstructure of heat-induced gels, however, can be dramatically altered with increasing ultrasonic time and cavitational pressure, from a spongy matrix with wider irregular pores, to a more dense and homogeneous alveolar network with fewer pores by reducing myosin oxidative changes as well as enhancing the intermolecular bonding interactions

[57][116].

Qin et al.

[49][108] took a particular approach to explain why the increased ultrasonic approach enhanced the wheat gluten added gel. They observed that the non-covalent interactions in the gluten structure (e.g., hydrogen bonds) were attenuated by the partial expression of protein molecules. The spatial structure of gluten reportedly promotes gel strength by creating novel and different linkages/relationships in the molecular structure, particularly covalent cross-links of inter-(μ-glutamine)-lysine. The use of Na

2SO

3/ultrasonic pretreatment increased the power of wheat gluten gel by up to 67% of the different pretreatments (e.g., alkaline, urea and Na

2SO

3) coupled with ultrasonication

[58][117]. The use of ultrasonic treatment generally results in higher protein solubility in various solvents, particularly over long periods of time. Ultrasonication increases the sum of electrostatic bonds and other non-covalent connections compared with covalent interactions in protein gel structure. This decreases the molecular weight and increases the solubility rate by hydrolyzing disulfide bonds by adding Na

2SO

3 into the reaction mixture

[52][111]. Under certain circumstances, the dispersion of protein molecules on the aqueous surface allows exposure of specific functional groups by the cavitation phenomenon during the ultrasonic application

[59][60][118,119].

3.3. Microwave (MW)

5.3. Microwave (MW)

Microwave (MW) heating has been reported as a non-conventional way of heating surimi gel, which generally focuses on the MW radiation effect on protein functional and structural attributes. Jiao, Cao, Fan, Huang, Zhao, Yan, Zhou, Zhang, Ye and Zhang

[3] reported that the MW heating protected proteins from oxidation, denaturing and aggregation during processing and preservation. MW heating proved to be effective against these changes in contrast with thermal hot water treatment. Feng, et al.

[61][120] examined the effects of both water bath and MW heating on silver carp protein, which showed that the MW heating showed better stability in Ca

2+ATPase activity and protein solubility than the proteins heated at water bath, which indicates less myosin exposure to oxidative changes and resulting denaturation. These inhibited changes also have a potential role in enhancing the gelling and textural abilities of the final product. Moreover, MW is a type of electromagnetic radiation with a frequency between 300 Hz to 300 GHz and a wavelength of around 1 cm and 1 mm. The polarization of water in food materials with MW high-frequency radiation will unfold protein molecules, breaking down non-covalent bindings, including disulfide connectivity and hydrogen bonding

[13][62][22,121]. Cao, Fan, Jiao, Huang, Zhao, Yan, Zhou, Zhang, Ye and Zhang

[63][47] stated that MW radiation could improve the efficiency and reaction rate of enzyme systems in a certain range of radiation frequencies. Qin, Luo, Cai, Zhong, Jiang, Zhao and Zheng

[49][108] have examined the impact of MW on the gelation process of mTGase added SPI. The increase in MW power up to 700 W decreased the solubility index, gel strength, elasticity, hardness and WHC of the proteins treated with mTGase. In contrast to untreated samples, thicker, more consistent mTGase-catalytic gels with more α-helices and β-turns and fewer portions of β-sheets were given at a constant frequency (3 GHz). The protein solubility decrease in MW treated samples was due to a reduction in the free SH content of protein gels caused by mTGase. In addition, due to the effect on hydrogen, intermolecular disulfide bonds, as well as electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions a significant number of insoluble protein aggregates can limit the solubility of proteins. Protein aggregates generally form due to oxidative changes and weaker intermolecular bonding interactions. In addition, MW heating also enhanced the stability of SH content by preventing the unfolding of amino acids caused by oxidative and aggregation changes

[61][120]. The accumulation of these insoluble aggregates of greater particle size could decrease the potential of the water to associate with protein molecules

[64][122].

The formation in MW-treated protein gels of a stable and solid well-aggregated microstructure with reduced particle size may be attributed to electrical polarization and the insoluble aggregation of proteins. The presence of this compact microstructure in surimi gels with increased gel strength and elasticity can validate improved textural properties, especially at increased MW capability

[65][123]. Ji, et al.

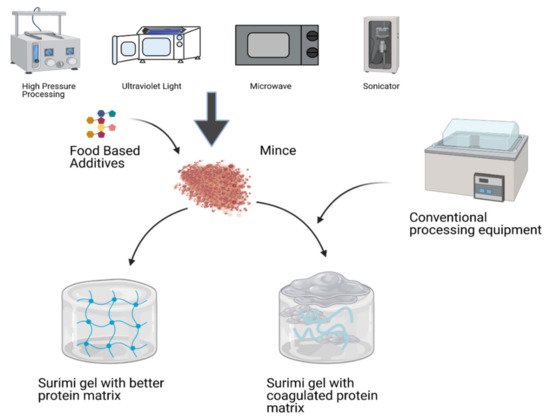

[66][124] reported that the surimi gel heated for 10 min at MW increased the breaking strength and gel firmness. As a result, it can be suggested that the surimi gelation at MW could increase the functional, microstructural and textural strength of the gel resulting from proper cross-linking of protein molecules. Thus, the resulting gel has better deformation and breaking strength as compared to the conventional gelation process. Protein behavior of surimi gel prepared with non-conventional and conventional techniques shown in

Figure 12. On the other hand, MW heating not only enhances the gelling attributes but also reduces the protein matrix. The MW consistent heating system could not result in a defective gel as in the conventional heating system temperature above boiling point increases water vapor pressure, resulting in a gel with structural defects

[67][68][125,126]. Besides that, the addition of konjac glucomannan (KGM) may improve the gel texture and structure by restricting the decline in protein secondary and tertiary structural properties induced during MW heating. It can also be interpreted that the addition of KGM improves the cross-linking of amino acids and reduces the MP polymerization

[69][127]. Therefore, KGM during MW heating not only acts as a filler but is also effective in protein cross-linking and interlinking.

Figure 12. Surimi gel prepared with non-conventional and conventional techniques. Non-conventional techniques show a more stable and well-established gel network than conventional processing equipment.

3.4. Ultraviolet

5.4. Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation can alter the protein structure by increasing the polymerization of protein side chains. The nature of the protein and the rate of irradiation are thought to be the two most important factors influencing the formation of cross-linking aggregates or molecular structures induced by protein denaturation and oxidation during this process

[70][71][128,129]. Synergistic activity between the mTGase increased the surimi gel power of minced mackerel

[26][13]. The mechanism behind the UV irradiation is that increases the hydrophobic interactions as compared to conventional heating, which indicates less protein denaturation (oxidation and aggregation)

[71][129]. Besides that, UV irradiation also gears up the formation of disulfide content induced during protein changes, but the formation of disulfide bonds during the UV process is less than the conventional heating methods

[72][130]. The UV irradiation process is consistent with stability in sulfhydryl content in fish sausage due to less irradiation-induced oxidation

[73][131]. Along with polysaccharides, UV could lead to better gel hardness, compactness and three-dimensional networks of surimi gel in comparison with control gel due to fewer increases in carbonyls and surface hydrophobicity. However, the use of UV for 20 min boosted gel intensity by 20% compared to the traditional gelation process

[74][132]. It can be concluded that UV light may strengthen the crosslinking of existing myosin chains in the actomyosin of surimi structure

[74][132]. However, due to the high UV light sensitivity of cysteine in the myosin, an excessive increase in treatment time would dramatically reduce the gelling performance

[71][129]. Cardoso, Mendes, Vaz-Pires and Nunes

[57][116] have investigated the impact of simultaneous addition of konjac flour (1%) and 40 min UV radiation at 250 nm, which increased the texture and surimi gel strength. The application of UV light with konjac flour produced maximum gel strength (63.2 N mm) and springiness (0.84), with the increased WHC. Th

is study indicate

s that the use of UV alone may not have a substantial effect on the texture consistency of prepared protein gels.

3.5. Ohmic Heating

5.5. Ohmic Heating

Ohmic heating is a technique in which alternating electric current passes through a food mixture. The food materials serve as resistors and their temperature is increased based on the Joule effect. The food materials serve as resistors and their temperatures vary due to the resulting air currents

[75][133]. An increase in temperature can influence the micro- and macro-structure and lead to certain phenomena such as water movement, protein coagulation and starch gelatinization. Meanwhile, the use of ohmic heating also prevents the activation of polyphenoloxidase and lipoxygenase, which are responsible for oxidative changes. Surimi added with egg white and treated with ohmic heating significantly reduced the protolysis compared to the water bath heating system. In addition, ohmic heating also increased the stability of cysteine, which is a key part of myosin and responsible for oxidative changes

[76][134]. Moreover, the application of ohmic heating to the surimi gel also significantly reduced the formation of disulfide bonds and resulted in an increase in total sulfhydryl content, which indicates the decline in the proteolysis process and results in proper MP interactions and gel formation

[77][135].

It is also a constructive aim to take the non-thermal impacts of ohmic applications into account, particularly when an alternating current is applied to food materials

[78][136]. While it is well known that ohmic heating effects on the textural and structural properties of food items have been observed, it depends on the characteristics of the food and the conditions of the process, including the process temperature, applied voltage and frequency

[71][79][129,137].

Kulawik

[80][138] investigated the textural and structural consistency of salt-added salmon gel using an ohmic treatment. Based on the findings by Tadpitchayangkoon, Park and Yongsawatdigul

[77][135], ohmic heating at 45 °C for 5 min before salting slightly improved the product appearance and quality. Another study demonstrated that ohmic heating at 90 °C with 60 Hz and 9 V/cm resulted in increased maximal cutting strength of surimi gel (15.6 N) as compared to the traditional heating system (20.4 N). The study showed that the lower temperature processing of surimi gel resulted in less denaturation and oxidation of the MPs in the various fish species

[81][139]. The textural characteristics of the thawed fish are found to be similar to those of fresh tilapia

[82][140]. One of the reasons this technology is considered superior to conventional ones is because of its better influence on surimi textural properties. A benefit of ohmic heating is that it will make the process of heating spread equally across the sample

[83][141]. Poor consistency or gel strength of fish can be obtained from an insufficient heating rate in traditional and slower heating methods

[78][136]. Traditional processing with slow water bath cooking resulted in poor quality surimi gel, while ohmic heating of surimi improved the quality of the gel matrix, texture and strength significantly

[81][139].

This research enlightened the value of ohmic application in improving the textural consistency of gel products. In addition, ohmic heating increased the textural attributes such as hardness, springiness and gumminess of Japanese whiting surimi gel at different temperatures (3, 60 and 160 °C/min), which developed a harder and more compact gel. It is obvious that the ohmic heating system provides better results relative to conventional water bath heating

[84][142]. [Chai and Park

[85][143]] reported that variations in time-temperature combinations and heating were the primary factors in varied textural properties during ohmic and water bath processed gel products. The applied voltage and product formulation were shown to be effective parameters to analyze the gel strength. Moreover, the role of modern processing technologies in enhanced textural properties of surimi gel is shown in

Table 12. It can be concluded from the current literature that ohmic heating could be effectively used to enhance the textural and functional properties of fish and seafood gel products.

Table 12.

Role of modern processing techniques on enhanced textural properties of surimi gel.

| Processing Technique |

Additives |

Role |

Results |

Reference |

| HPP |

Kappa-carrageenan (KC) |

Oligosaccharids, antioxidants and cryoprotectants |

Surimi gel treated with KC showed better WHC and gel strength on HPP (300 MPa), by improving the water state and structural properties. |

[86][53] |

| HPP |

mTGase |

Microbial |

The mTGase treated surimi gel showed increased fracture stress, strain and gel strength when cooked at 300 MPa processing. |

[87][144] |

| Ultrasonication |

Soybean polysaccharide (SSPS) |

Polysaccharide, antioxidants, funtional and gelling |

The SSPS added surimi gel revealed enhanced whiteness and gelling properties during frozen storage combined with ultrasonication. |

[53][112] |

| Ultrasonication |

Wheat gluten (WG) |

Protien additive, functional and gelling |

Wheat gluten-SPI gels with ultrasonication led to increase in textural properties by improving β-sheets, decreased α-helices and β-turns. |

[26][13] |

| Microwave |

NaCl |

Functional and mechanical |

The mechanical, structural and textural characteristics of NaCl-treated surimi gel improved after 80 s heating of MW (15 W/g). |

[88][145] |

| Microwave |

Konjac glucomannan (KGM) |

Oligosaccharide, antioxidant and functional |

Microwave heated KGM surimi gel displayed better starching of protein molecules and dense KGM-protein network. |

[66][124] |

| Ultraviolet |

Konjac flour (KF) |

Dietary fiber, gelling |

KF (1%) and 250 nm UV for 40 min increased the gel hardness (63.2 N) and springiness (0.84). |

[57][116] |

| Ohmic heating |

Corn starch (CS) |

Carbohydrate, functional and thermo-stable |

CS-surimi gel displayed inferior gel network due to starch gelatinization. But the control surimi gel exhibited improved hardness and gel strength when processed with ohmic technique as compared to water bath cooked gel. |

[84][142] |

| Ohmic heating |

Diced carrot (DC) |

Sensory and functional |

DC added surimi of Pacific whiting (PW) and Alaska Pollock (AP) reported increased hardness and cohesiveness when ohmically heated at 90 °C. |

[15][24] |