Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 3 by Jason Zhu.

It is essential to understand the variables that explain and predict the behaviour of starting up a new company in a regional context. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) reports have a sufficient theoretical foundation for quality studies in this field. In addition, a valid and reliable causal model is designed that includes all personal and contextual GEM variables. The hypotheses of the proposed model are based on the existing causal relationships in the literature, using GEM data in its formulation. The model is comprehensive and practical because it significantly predicts entrepreneurial behaviour, particularly entrepreneurial intention and action.

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor

- entrepreneurial behaviour

- entrepreneurial intention

1. Background

1.1. Variables Influencing Entrepreneurial Behaviour According to the Literature

It is accepted in the literature on entrepreneurship at the regional level that entrepreneurs are the critical element in the process of creating a new venture. This is why entrepreneurship requires entrepreneurial behaviour (intention and action) [1][2][3]. In turn, it has been found that entrepreneurial behaviour depends on contextual variables and personal variables, the latter having been more studied [4][5].

Their importance is very high regarding contextual variables considering that entrepreneurial behaviour develops in a specific context, although some contextual variables are more favourable than others [6][7]. Contextual variables are often classified in the literature as formal institutional variables and informal institutional variables. From a formal institutional perspective, the importance of government policies and programmes, as well as infrastructures (e.g., physical, commercial, technological and financial), market development and innovation transfer is highlighted [8][9]. The role of the education system has also been emphasized in the literature because it enables the development of entrepreneurial vocation, values related to self-employment, skills to create a business and entrepreneurial intention [9][10][11]. Regarding the informal institutional variables that influence entrepreneurial behaviour, the literature underlines the role of culture, which develops over time through the adoption and internalisation, usually unconsciously, of norms, beliefs, practices and customs [12]. In particular, it has been found that cultural diversity can help to explain regional differences in entrepreneurship, as the decision to start a new venture depends on the cultural context in which it takes place [13][14]. Individualistic cultures have also been found to be more conducive to entrepreneurship than collectivistic cultures, as, in the former, people consider their interests before those of the group [15][16].

Regarding the personal variables linked to entrepreneurial behaviour, the literature highlights entrepreneurial intention, which is the variable that best predicts the behaviour of creating a new company at the regional level [17][18]. For these reasons, intention is the central variable in most studies on entrepreneurial behaviour, most of which aim to design causal models to predict it. The remaining personal variables, and occasionally some contextual variables, constitute the independent variables in such causal models [19][20][21]. Regarding its definition, entrepreneurial intention is conceived as an entrepreneur’s propensity to make an intentional, deliberate and planned decision to create a new venture [20][22].

Two of the most widely used models in the literature to predict entrepreneurial intention are Shapero and Sokol’s [23] entrepreneurial event model (EEM) and Ajzen’s [24] theory of planned behaviour (TPB) [25][26]. In the model by Shapero and Sokol, entrepreneurial intention depends on three variables: perceived desirability, which derives from a perceived reasonable business opportunity; perceived feasibility, based on the perception of one’s capabilities; and propensity to act [27][28]. However, it is the TPB model that predominates in the literature due to its higher predictive power [29][30]. The TPB model’s intention to start a new venture depends on the attitude towards entrepreneurship, perceived control and subjective norm [20][31]. Attitude corresponds to desirability, included in the EEM model, and is defined as the personal valuation about being an entrepreneur [20][31]. Regarding perceived behavioural control, this is a variable similar to perceived feasibility in the Shapero and Sokol model and is defined as an individual’s assessment of the extent to which they can perform a specific behaviour [20][31][32]. Perceived control is a construct closely related to self-efficacy, defined as the belief in resources and competencies to achieve one’s goals [33][34]. Finally, subjective norms refer to how the subject himself perceives that his behaviour will be accepted by his belonging or reference group [20][30]. The influence of subjective norms is similar to the process of entrepreneurial role adoption by the subject that she or he observes in a known person or a family member, which largely explains the succession process [35][36].

Despite the many studies conducted and the findings obtained, the literature points out the limitations of existing causal models in predicting complex entrepreneurial behaviour in a regional context. It is mainly due to the small number of variables they incorporate [37][38]. On the other hand, the researchers of predictive behavioural studies need quality traditional data sources for a wide range of variables and countries [3]. In order to respond to these demands, several researchers suggest enriching predictive models by incorporating new variables and new relationships, as well as variables that, together with intention, reflect effective entrepreneurial behaviour [39]. To study more deeply the quality of data from institutional data sources has also been suggested [39][40][41].

1.2. Variables Influencing Entrepreneurial Behaviour at the Institutional Level: The Case of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor

According to the GEM, the decision to start a new business depends on a broad set of personal and contextual variables, all of which are equally important[42]. Despite their equal importance, in GEM reports, contextual variables can influence personal variables, although GEM does not specify the nature of this relationship [43][44]. Moreover, as mentioned above, in GEM reports, entrepreneurial intention is just another personal variable [42][3].

The contextual variables are considered an essential part of business creation and directly influence entrepreneurial opportunities, competencies, and preferences. The source of information on these variables is the National Experts Survey, a standard GEM methodology to capture expert judgments to evaluate regional variables [42][3]. Regarding their measurement, the values of the contextual variables represent the average scalar data per country that come from the responses of entrepreneurship experts to specially designed questionnaires. Regarding personal variables, the information is obtained by GEM through the design and application of the Adult Population Survey (APS), a unique and comprehensive questionnaire administered to a minimum of 2000 adults in each GEM country. All personal variables included in GEM reports refer to average percentages of the population aged 18–64 by country and are based on the perceptions and statements of the population [42][3].

Finally, it should be noted that GEM reports also provide several outcome variables or indicators directly or indirectly related to entrepreneurship. It has been included the TEA (Total Early stage Entrepreneurial Activity) indicator, the most critical outcome indicator in the GEM reports [42]. GEM defines TEA as the percentage of the population aged 18–64 who are either a nascent entrepreneur or an owner-manager of a new business. Its inclusion responds to suggestions by several researchers to include in causal models, along with entrepreneurial intention, some variable that reflects the “action” inherent to entrepreneurial behaviour [43][45]. Moreover, TEA will be the variable used to achieve objective 4.

2. Hypotheses and Model Development

The hypotheses and the predictive model proposed are presented below. The model has been designed to consider the contributions of other researchers in this field and use GEM variables and country data.

First, it has been found in the literature that entrepreneurial behaviour depends on contextual or environmental factors, which in turn influence personal variables [25][46]. Among the environmental factors that influence entrepreneurship culture and education stand out [47][48]. Regarding culture, it refers to the social value structure of a community or region [49][50]. It should be noted that culture carries social legitimacy. Therefore, to the extent that a culture values entrepreneurship, it will be highly valued and socially accepted, thus creating a favourable and supportive context for entrepreneurship [12][51][52].

On the other hand, education always considers the current socio-economic context, including the entrepreneurial field. Through educational design and practice and/or it will try to drive the changes and improvements that the context requires [53][54]. In particular, it has been confirmed that culture and education directly influence the intention and action to create a new venture, and indirectly through the subject’s perceptions about the entrepreneurial context, in particular about the basic infrastructures for entrepreneurship [55][56]. Considering the above, the first two hypotheses state:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

According to GEM data, education and culture related to entrepreneurship directly and positively influence entrepreneurial intention and action.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

According to GEM data, education and culture related to entrepreneurship directly and positively influence the perception of basic infrastructures for entrepreneurship.

Government policies and programmes to foster entrepreneurship at the regional level do not originate in a vacuum, but through interaction with the context [57][58]. It has been found in the literature that such policies and programmes depend on demands related to the degree of adequacy of the physical, technological, financial and commercial infrastructures needed for entrepreneurship and existing in the region [59][60]. It is one of the missions and social responsibilities of governments to facilitate the existence of a favourable context for entrepreneurship, improving access to finance and developing appropriate taxation, among other measures, all within the limits of their capabilities, principles and political inclination [60][61][62]. It should be noted that, as in the private sector, the satisfaction of the needs, wants, and expectations of the recipients and beneficiaries of government policies have an impact on the perception of those policies, the reputation of the issuing organisation and the loyalty to it [63][64]. So much so that governments and the public sector are using tools from the private sector to improve the adaptation of their policies to the context, such as market orientation [59][65][66]. Considering the above, the following hypothesis is expressed as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

According to GEM data, perceptions about infrastructures and primary conditions for entrepreneurship directly and positively influence perceptions about government policies and programmes related to entrepreneurship.

The influence of government policies and programmes on people’s perceptions, in whatever domain they are targeted (e.g., health and education), is due to both internal subject and external factors [67][68]. In particular, perceptions of government policies and programmes related to entrepreneurship, including those related to innovation, have been shown to influence perceptions of entrepreneurship opportunity and the ease of undertaking entrepreneurship [48][69][70]. Such perceptions, which indirectly and positively influence entrepreneurial intention and action, are essential in the early stages of entrepreneurship [71][72][73]. Entrepreneurs are risk takers (e.g., financial risks) and sensitive to institutional support or disincentive, whether real or only perceived. Thus, subjects who perceive opportunity and ease of entrepreneurship (e.g., legislative, governmental, and commercial) possess greater entrepreneurial intention and action. Their confidence, hope, and dispositional optimism are higher when the perceived risk is lower [27][71][72]. Given the above, the following hypothesis states:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

According to GEM data, perceptions about government policies and programmes on entrepreneurship positively and directly influence perceptions about entrepreneurial opportunities and facilities.

Subjective norm is defined as the belief that people close to the subject (e.g., family and friends) might accept or reject a particular behaviour [25][24][74]. Therefore, the subjective norm represents a code of conduct that prescribes or prohibits behaviour in members of a group [75][76]. Concerning antecedents, in the context of entrepreneurship, the perception of how contextual factors facilitate entrepreneurship has been shown to directly or indirectly influence subjective norm formation [25][77][78]. It should be noted that the influence of perceptions and the power of the subjective norm is particularly relevant within the group of people whose influence contributes to maintaining perceptions and the subjective norm [78][79][80]. Such influence is more significant when there are favourable expectations regarding the attainment of benefits from entrepreneurship and when the subject possesses a high self-concept of an entrepreneur [81][82]. Therefore, the following hypothesis stipulates that:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

According to GEM data, perceptions about entrepreneurial opportunities and facilities directly and positively influence subjective norms.

Values represent a person’s predisposition toward an object or behaviour, in this case, the behaviour of starting a new venture [83][84]. Values are criteria for action at the origin of any behaviour, are highly stable and are formed during the socialisation process [85][86]. There are many personal value categories associated with entrepreneurship, and some researchers claim that entrepreneurs can be differentiated from each other solely based on their value structure [86][87]. Regarding the antecedents of personal values, the subjective norm has been found to influence their formation directly due to the motivational component that values possess [88][89]. It has been shown that people adopt values when they perceive that other significant agents share these values [78][88][90]. Thus, values represent the result of the subject’s self-adjustment effort to a social context [91][92]. Based on the above, the following hypothesis states:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

According to GEM data, the subjective norm directly and positively influences values related to entrepreneurship.

Values influence a multitude of variables. For example, it has been confirmed by several researchers that personal values influence self-efficacy and other related constructs, such as perceived control, the belief in personal agency and the competencies perceived by the subject, in this case, the entrepreneur [91][93]. Particularly in the field of entrepreneurship, it has been shown that people who possess pro-entrepreneurship values, which depend on the subjective norm, are considered competent and self-efficacious in entrepreneurship [94][95]. Self-efficacy is a central concept in the context of entrepreneurship. It is defined as an individual’s belief or confidence in his or her competence to mobilise the resources and activities necessary to successfully execute a specific task within a given context [94][95][96]. The relationship between personal values and self-efficacy occurs within a motivational process of confirming attitudes, beliefs, perceptions and expectations, particularly in cultures that value and reward individual performance and achievement [95][97][98].

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

According to GEM data, personal values related to entrepreneurship directly and positively influence entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is the best predictor of entrepreneurial intention and start-up behaviour [99][100][101]. It is a motivational and adequate antecedent of entrepreneurial intention and behaviour regardless of the regional level [95][102]. Self-efficacy enables the entrepreneur to overcome challenges when starting up a business and use the negative feedback they receive to improve their performance in that process [95][103][104].

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

According to GEM data, self-efficacy directly and positively influences entrepreneurial intention and start-up behaviour.

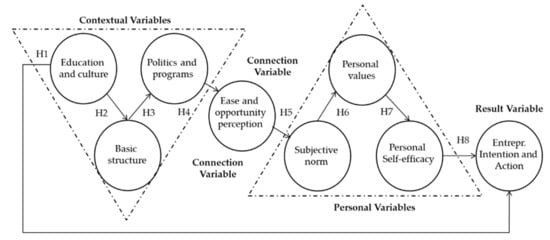

Figure 1 presents the model proposed. The model is in line with other models recently developed in the literature [25][76]. As proposed by the GEM and other researchers, the model represents a unidirectional sequential path from contextual variables to personal variables, culminating in entrepreneurial intention and action [43][105]. The model starts with three contextual variables: “Education and culture”, “Basic structure”, and “Politics and programmes”. These contextual variables, directly and indirectly, influence the “Ease and opportunity perception” variable, which connects the contextual variables with the personal variables (“Subjective norm”, “Personal values”, and “Personal self-efficacy”). The variable “Personal self-efficacy” is the one that directly influences the latent dependent variable, “Entrepreneurship intention and action”.

Figure 1. Research proposed model. Source: researchers.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Profile

Data were obtained from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor platform (www.gemconsortium.org, accessed on 23 June 2021), similar to other researchers [3][106]. Specifically, the information included in the databases available in Excel for 2020 werew used, which is the latest data available on the GEM website. The 45 countries (N = 45) for which data were available for all variables included were selected. It should be noted that the effort and rigour of data collection for GEM that has occurred every year mean this dataset has received a significant amount of respect across the social sciences [106][107]. Finally, the high validity, reliability and unidimensionality of the GEM data have recently been confirmed through the Rasch mathematical model [3].

3.2. Variables and Constructs

First, the observed personal and contextual variables used were included in the latest GEM report 2020–2021 (www.gemconsortium.org, accessed on 25 June 2021), and are explained above. In addition, the TEA (Total early stage Entrepreneurial Activity) indicator was selected as an outcome variable. Second, to identify the latent variables or constructs, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out. This analysis was carried out using the principal components extraction method and the Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization, as performed by other researchers [25]. After the analyses, eight latent variables (factors) were obtained. The sum of the squared loads of the rotation explained 87.28% of the variance accumulated through the eight resulting factors. These variables were Education and Culture (ECU), Basic Infrastructures (BIN), Government Policies and Programmes (GPP), Perceptions (PER), Subjective Norm (SUN), Personal Values (PVA), Self-efficacy (SEF) and Entrepreneurial Intention and Action (EIA). Two observed variables were eliminated through this factor analysis: Fear of Failure (personal variable) and Internal Market Dynamics (Contextual variable). Additionally, the reliability changed from 0.86 to 0.89 by eliminating these variables. Only two items in five latent variables were accepted because these items had a low correlation with other latent variables, and the correlation between the items belonging to the same variable was greater than 70% [108].

3.3. Methodology

Firstly, data were examined using the SPSS-25 programme to obtain descriptive indicators. The Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) method was applied through SmartPLS-3 software (3.3.2 version) to minimize the residual variances of the endogenous variable. PLS was selected due to its potential to explain the theory and predict human behaviour [109]. In addition, PLS allows the use of a wide range of sample sizes and reflective variables, and it shows more reliable results and does not require a normal distribution of data [109].

The PLS-SEM approach implies studying the measurement model and the study of the structural model. The Measurement and Structural models take the general form as follows:

Measurement model: X = C′Y + ε

Structural model: Y = B′Y + ζ

-

X is a J by 1 vector of indicators;

-

Y is a P by 1 vector of latent variables;

-

C is a P by J matrix of loadings;

-

B is a P by P matrix of path coefficients;

-

ε is a J by 1 vector of the residuals of indicators;

-

ζ is a P by 1 vector of the residuals of latent variables.

The reflective indicators in the latest GEM report 2020–2021 (www.gemconsortium.org, accessed on 25 June 2021) were used. These are reflective indicators because they meet the criteria proposed by Jarvis, MacKenzie and Podsakoff [110]. As proposed by other researchers, an Importance-Performance Analysis (IPMA) and Multigroup Technique were included to achieve objectives 3 and 4, respectively [25][111]. Finally, it should be noted that the ultimate guidelines in applying PLS-SEM in research were followed in the application of PLS-SEM [109][112].

References

- Clausen, T.H. Entrepreneurial thinking and action in opportunity development: A conceptual process model. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 21–40.

- Michaelis, T.L.; Carr, J.C.; Scheaf, D.J.; Pollack, J.M. The frugal entrepreneur: A self-regulatory perspective of resourceful entrepreneurial behavior. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 35, 105969.

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Kobylinska, U.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D. Exploring personal and contextual variables of the global entrepreneurship monitor through the Rasch Mathematical Model. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1838.

- Simón-Moya, V.; Revuelto-Taboada, L.; Guerrero, R.F. Institutional and economic drivers of entrepreneurship: An international perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 715–721.

- Ahadi, S.; Kasraie, S. Contextual factors of entrepreneurship intention in manufacturing SMEs: The case study of Iran. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 633–657.

- Matos, S.; Hall, J. An exploratory study of entrepreneurs in impoverished communities: When institutional factors and individual characteristics result in non-productive entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 32, 134–155.

- Pérez-Macía, N.; Fernández-Fernández, J.L. Personal and contextual factors influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of people with disabilities in Spain. Disabil. Soc. 2021.

- Touzani, M.; Jlassi, F.; Maalaoui, A.; Hassine, R.B.H. Contextual and cultural determinants of entrepreneurship in pre- and post-revolutionary Tunisia. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2015, 22, 160–179.

- Cherrier, H.; Goswami, P.; Ray, S. Social entrepreneurship: Creating value in the context of institutional complexity. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 245–258.

- Tsordia, C.; Papadimitriou, D. The Role of Theory of Planned Behavior on Entrepreneurial Intention of Greek Business Students. Int. J. Synerg. Res. 2015, 4, 23–37.

- Bergmann, H.; Hundt, C.; Sternberg, R. What makes student entrepreneurs? On the relevance (and irrelevance) of the university and the regional context for student start-ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 53–76.

- Liñán, F.; Fernandez-Serrano, J. National culture, entrepreneurship and economic development: Different patterns across the European Union. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 685–701.

- Audretsch, D.B.; Obschonka, M.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. A new perspective on entrepreneurial regions: Linking cultural identity with latent and manifest entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 48, 681–697.

- Canestrino, R.; Cwiklicki, M.; Magliocca, P.; Pawełek, B. Understanding social entrepreneurship: A cultural perspective in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 132–143.

- Liñán, F.; Fernández, J.; Romero, I. Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: The mediating effect of culture. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2013, 33, 21–47.

- Martínez-Rodriguez, I.; Callejas-Albiñana, F.E.; Callejas-Albiñana, A.I. Economic and socio-cultural drivers of necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship depending on the business cycle phase. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 21, 373–394.

- Chien-Chi, C.; Sun, B.; Yang, H.; Zheng, M.; Li, B. Emotional competence, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention: A study based on China college students’ social entrepreneurship project. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 547627.

- Yan, X.; Gu, D.; Liang, C.; Zhao, S.; Lu, W. Fostering sustainable entrepreneurs: Evidence from China college students’ “Internet Plus” innovation and entrepreneurship competition (CSIPC). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3335.

- Esfandiar, K.; Sharifi-Tehrani, M.; Pratt, S.; Altinay, L. Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 172–182.

- Ohanu, I.B.; Shodipe, T.O. Influence of the link between resources and behavioural factors on the entrepreneurial intentions of electrical installation and maintenance work students. J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 10, 13.

- Bae, T.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 217–254.

- Moriano, J.A.; Gorgievski, M.; Laguna, M.; Stephan, U.; Zarafshani, K. A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. J. Career Dev. 2011, 39, 162–185.

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In Encylopedia of Entrepreneurship; Kent, C., Sexton, L., Vesper, K., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 72–90.

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211.

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Kobylinska, U.; García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Nazarko, L. Antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among young people: Model and regional evidence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6993.

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332.

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432.

- Mikić, M.; Horvatinović, T.; Turčić, I. A closer look at entrepreneurial intentions. Econ. Bus. Lett. 2020, 9, 361–369.

- Fitzsimmons, J.R.; Douglas, E.J. Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 431–440.

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381.

- Vamvaka, V.; Stoforos, C.; Palaskas, T.; Botsaris, C. Attitude toward entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention: Dimensionality, structural relationships, and gender differences. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 9, 5.

- Van Gelderen, M.; Kautonen, T.; Wincent, J.; Biniari, M. Implementation intentions in the entrepreneurial process: Concept, empirical findings, and research agenda. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 51, 923–941.

- Ciuchta, M.P.; Finch, D. The mediating role of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions: Exploring boundary conditions. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2019, 11, e00128.

- Powers, B.; Le Loarne-Lemaire, S.; Maalaoui, A.; Kraus, S. “When I get older, I wanna be an entrepreneur”: The impact of disability and dyslexia on entrepreneurial self-efficacy perception. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 434–451.

- Cardella, G.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; García, J.C.S. Entrepreneurship and family role: A systematic review of a growing research. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2939.

- Georgescu, M.A.; Herman, E. The impact of the family background on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4775.

- Sedeh, A.; Abootorabi, H.; Zhang, J. National social capital, perceived entrepreneurial ability and entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 334–355.

- Ndofirepi, T.M. How spatial contexts, institutions and self-identity affect entrepreneurial intentions. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 153–174.

- González-Serrano, M.H.; González-García, R.J.; Carvalho, M.J.; Calabuig, F. Predicting entrepreneurial intentions of sports sciences students: A cross-cultural approach. J. Hosp. Leis. Sports Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100322.

- Halberstadt, J.; Schank, C.; Euler, M.; Harms, R. Learning sustainability entrepreneurship by doing: Providing a lecturer-oriented service learning framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1217.

- Doanh, D.C. The role of contextual factors on predicting entrepreneurial intention among Vietnamese students. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 9, 169–188.

- Bosna, N.; Hill, S.; Ionescu-Somers, A.; Kelley, D.; Guerrero, M.; Schott, T. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)—2020/2021 Global Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School: London, UK, 2021.

- Herrington, M.; Coduras, A. The national entrepreneurship framework conditions in sub-Saharan Africa: A comparative study of GEM data/National Expert Surveys for South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and Madagascar. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 1–24.

- Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R.; Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Lorenzo-Gómez, J.D.; Ruiz-Navarro, J. What you know or who you know? The role of intellectual and social capital in opportunity recognition. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 566–582.

- Ali, J.; Jabeen, Z. Understanding entrepreneurial behavior for predicting start-up intention in India: Evidence from global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM) data. J. Public Aff. 2020, 22, e2399.

- Dileo, I.; García-Pereiro, T. Assessing the impact of individual and context factors on the entrepreneurial process. A cross-country multilevel approach. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1393–1441.

- Castaño, M.S.; Méndez, M.T.; Galindo, M.Á. The effect of public policies on entrepreneurial activity and economic growth. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5280–5285.

- Zhao, Q.J.; Zhou, B.F.; Linm, J.H. Influence of environmental perception on college students’ entrepreneurial intention and gender differences. J. Hum. Agric. Univ. 2019, 1, 89–96.

- Hofstede, G. The GLOBE debate: Back to relevance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 1339–1346.

- Dheer, R.J.S. Cross-national differences in entrepreneurial Activity: Role of culture and institutional factors. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 813–842.

- Fernández-Serrano, J.; Berbegal, V.; Velasco, F.; Expósito, A. Efficient entrepreneurial culture: A cross-country analysis of developed countries. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 105–127.

- Çelikkol, M.; Kitapçi, H.; Döven, G. Culture’s impact on entrepreneurship & interaction effect of economic development level: An 81 country study. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 777–797.

- Haddad, G.; Esposito, M.; Tse, T. The social cluster of gender, agency and entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2016, 28, 431–450.

- Boldureanu, G.; Ionescu, A.M.; Bercu, A.M.; Bedrule-Grigorut, M.V.; Boldureanu, D. Entrepreneurship education through successful entrepreneurial models in higher education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1267.

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93.

- Wu, F.; Mao, C. Business environment and entrepreneurial motivations of urban students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1483.

- Robson, P.J.A.; Wijbenga, F.; Parker, S. Entrepreneurship and policy. Challenges and directions for future research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2009, 27, 531–535.

- Spyridaki, N.A.; Ioannou, A.; Flamos, A. How can the context affect policy decision-making: The case of climate change mitigation policies in the Greek building sector. Energies 2016, 9, 294.

- Martínez-Fierro, S.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Ruiz-Navarro, J. Impact of high-growth start-ups on entrepreneurial environment based on the level of national economic development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1007–1020.

- Grimaldi, R.; Kenney, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, M. 30 years after Bayh-Dole: Reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 1045–1144.

- Heinonen, J.; Hytti, U.; Cooney, T.M. The context matters. Understanding the evolution of Finnish and Irish entrepreneurship policies. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 1158–1173.

- Farinha, L.; Lopes, J.; Bagchi-Sen, S.; Renato, J.; Oliveira, J. Entrepreneurial dynamics and government policies to boost entrepreneurship performance. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 72, 100950.

- Di Foggia, G.; Arrigo, U. The political economy of public spending on Italian rail transport: A European view. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. 2016, 11, 192–206.

- Friedl, C.; Reichl, J. Realizing energy infrastructure projects. A qualitative empirical analysis of local practices to address social acceptance. Energy Policy 2016, 89, 184–193.

- Obaji, N.O.; Olugu, M.U. The role of government policy in entrepreneurship development. Sci. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 2, 109–115.

- Mintrom, M.; Norman, P. Policy entrepreneurship and policy change. Policy Stud. J. 2009, 37, 649–667.

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Van der Zwan, P.; Thurik, R. Sustainable entrepreneurship: The role of perceived barriers and risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 1133–1154.

- Ejelöv, E.; Nilsson, A. Individual factors influencing acceptability for environmental policies: A review and research agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2404.

- Wu, Y.J.; Yuan, C.H.; Pan, C.I. Entrepreneurship education: An experimental study with information and communication technology. Sustainability 2018, 10, 691.

- Davari, A.; Farokhmanesh, T. Impact of entrepreneurship policies on opportunity to startup. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2017, 7, 431–438.

- Pinkse, J.; Groot, K. Sustainable entrepreneurship and corporate political activity: Overcoming market barriers in the clean energy sector. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 633–654.

- Block, J.; Sandner, P.; Spiegel, F. How do risk attitudes differ within the group of entrepreneurs? The role of motivation and procedural utility. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 183–206.

- Su, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, T.; Lin, C.L.; Xu, D. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention of university students in China: Integrating the perceived university support and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4519.

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499.

- Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R.; Cialdini, R.B. A focus theory of normative conduct: When norms do and do not affect behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 1002–1012.

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Parra-López, E.; Barrientos-Báez, A. young consumers’ intention to participate in the sharing economy: An integrated model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 430.

- Young, P. The evolution of social norms. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2015, 7, 359–387.

- Legros, S.; Cislaghi, B. Mapping the social-norms literature: An overview of reviews. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 62–80.

- Burrus, J.; Moore, R. The incremental validity of beliefs and attitudes for predicting mathematics achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 50, 246–251.

- Fang, W.T.; Ng, E.; Wang, C.M.; Hsu, M.L. Normative beliefs, attitudes, and social norms: People reduce waste as an index of social relationships when spending leisure time. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1696.

- Hong, I.B. Social and personal dimensions as predictors of sustainable intention to use facebook in Korea: An empirical analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2856.

- Christensen, P.N.; Rothgerber, H.; Wood, W.; Matz, D.C. Social norms and identity relevance: A motivational approach to normative behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 1295–1309.

- Tomczyk, D.; Lee, J.; Winslow, E. Entrepreneurs’ personal values, compensation, and high growth firm performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 66–82.

- Maresch, D.; Harms, R.; Kailer, N.; Wimmer-Wurm, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 172–179.

- Jahanshahi, A.A.; Brem, A.; Bhattacharjee, A. Who takes more sustainability-oriented entrepreneurial actions? The role of entrepreneurs’ values, beliefs and orientations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1636.

- Sotiropoulou, A.; Papadimitriou, D.; Maroudas, L. Personal values and typologies of social entrepreneurs. The case of Greece. J. Soc. Entrep. 2021, 12, 1–27.

- Usman, B.; Yenita. Understanding the entrepreneurial intention among international students in Turkey. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 10–32.

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.K. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and proenvironmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90.

- Dalila, D.; Latif, H.; Jaafar, N.; Aziz, I.; Afthanorhan, A. The mediating effect of personal values on the relationships between attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and intention to use. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 153–162.

- Cho, H.; Lee, J. The influence of self-efficacy, subjective norms, and risk perception on behavioral intentions related to the H1N1 flu pandemic: A comparison between Korea and the US Hichang. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 18, 311–324.

- Fornara, F.; Pattitoni, P.; Mura, M.; Strazzera, E. Predicting intention to improve household energy effciency: The role of value-belief-norm theory, normative and informational influence, and specific attitude. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 1–10.

- Tamar, M.; Wirawan, H.; Bellani, E. The Buginese entrepreneurs; the influence of local values, motivation and entrepreneurial traits on business performance. J. Enterprising Communities 2019, 13, 438–454.

- Brändle, L.; Berger, E.S.C.; Golla, S.; Kuckertz, A. I am what I am—How nascent entrepreneurs’ social identity affects their entrepreneurial self-efficacy. J. Bus Ventur. Insights 2018, 9, 17–23.

- Zhang, J.; Huang, J. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the impact of the post-pandemic entrepreneurship environment on college students’ entrepreneurial intention. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 643184.

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419.

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy and health behavior. In Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine; Baum, A., Newman, S., Wienman, J., West, R., McManus, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 160–162.

- Wei, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. How does entrepreneurial self-efficacy influence innovation behavior? Exploring the mechanism of job satisfaction and Zhongyong Thinking. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 708.

- Caines, V.; Earl, J.K.; Bordia, P. Self-employment in later life: How future time perspective and social support influence self-employment interest. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 448.

- Asimakopoulos, G.; Hernández, V.; Miguel, J.P. Entrepreneurial intention of engineering students: The role of social norms and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4314.

- Hussain, I.; Nazir, M.; Hashmi, S.B.; Shaheen, I.; Akram, S.; Waseem, M.A.; Arshad, A. Linking green and sustainable entrepreneurial intentions and social networking sites; the mediating role of self-efficacy and risk propensity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7050.

- Anwar, I.; Jamal, M.T.; Saleem, I.; Thoudam, P. Traits and entrepreneurial intention: Testing the mediating role of entrepreneurial attitude and self-efficacy. J. Int. Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2021, 13, 40–60.

- Dölarslan, E.A.; Koçak, A.; Walsh, P. Perceived Barriers to Entrepreneurial Intention: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy. J. Dev. Entrep. 2020, 25, 1–23.

- Li, C.; Bilimoria, D.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X. Gender role characteristics and entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A comparative study of female and male entrepreneurs in China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 585803.

- To, C.K.M.; Guaita-Martínez, J.M.; Orero-Blat, M.; Chau, K.P. Predicting motivational outcomes in social entrepreneurship: Roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and situational fit. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 209–222.

- Yang, M.M.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. What explains the degree of internationalization of early-stage entrepreneurial firms? A multilevel study on the joint effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship, and home-country institutions. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101114.

- Santos, G.; Silva, R.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Marques, C.; Leal, C. Nascent entrepreneurs’ motivations in European economies: A gender approach using GEM data. J. Glob. Mark. 2017, 30, 122–137.

- Peterson, M. Modeling country entrepreneurial activity to inform entrepreneurial marketing research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 105–116.

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94.

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 2–24.

- Jarvis, C.B.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, M. A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 199–218.

- Buhalis, D.; Parra-López, E.; Martínez-González, J.A. Influence of young consumers’ external and internal variables on their e-loyalty to tourism sites. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100409.

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538.

More