Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Zhuo-Ming REN.

The ways people use words online can furnish psychological processes about their beliefs, fears, thinking patterns, and so on. Extracting from online employees’ reviews on the workplace community websites, the psychological effects of employees during the phase of the COVID-19 pandemic can be quantified. Affected by the pandemic after 2020, although the overall evaluation of digital companies employees was tending to be better, were work–life balance, culture and values, senior management, career opportunities, and salary and benefits, which were still getting worse.

- online employee reviews

- psychological effect

- digital company

- COVID-19 pandemic

1. Introduction

During COVID-19, countries around the world are under lockdown and millions of people cannot leave their homes. People are substantially suffering from many symptoms of psychological stress, such as greater levels of anxiety, depression, and distress [1,2,3,4,5][1][2][3][4][5]. Particularly, the vulnerable groups range from health care workers, women, younger people, the self-employed, to the people with psychological processes who were plagued by the pandemic [6]. Interventions for mental health are urgently needed for preventing mental health problems [7,8][7][8]. Recently, researchers have been searching for solutions to the physical and psychological needs of health care workers [9,10][9][10]. During the pandemic period, it is crucial to make arrangements in working conditions in a way to increase job satisfaction, reduce burnout among health care workers, and provide necessary psychological support [11]. For example, the psychological contract on employees’ safety behavior in the context of the early epidemic situation [12]. The mental issues and psychological resilience of healthcare professionals who have the closest contact with the patients [13]. The anxiety levels of the emergency medicine professionals who are on the front line in the hospitals should be treated, and they should be provided psychological and behavioral support [14]. Health managers and policymakers need to make a move immediately to find solutions for the physical and psychological needs of health employees [15,16][15][16]. The health education programs should be easily accessible, affordable, and available to the general population [17]. Programs such as a mobile app or a digital learning package are designed to address the current and anticipated psychological impacts of the mental health of health care workers [18,19][18][19].

In addition to the difficulties encountered by health care workers, industries are also facing a halt. Offices are closed, shopkeepers are experiencing fewer sales, and museum activities are not ready to serve visitors during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic [20]. The coronavirus pandemic has transformed the way wpeople work, with many employees working under isolation and difficult conditions [21]. Wu et al. [22] believes that ensuring mutual consideration is the best way for hotel employees and employers to pull through a crisis. Pathak et al. [23] examined the impact of the psychological capital of owners and the managers of a budget hotel on the organizational resilience during COVID-19, and could give advice to the owners and managers of budget hotels to navigate through the stages of the COVID-19 pandemic for speedy recovery. Work–family conflict’s mediating role and psychological resilience’s moderating role on the perceived supervisor support of yacht captains and their turnover intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic in the tourism industry are also investigated [24]. In general, understanding work–life wellness contributes to improving the physical health, mental health, and productivity of remote workers. Due to physical distancing guidelines associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, many employees have been working from home, often without adequate training and resources [25].

After the world went into lockdown, the pandemic COVID-19 has affected the mental health of food retailers, food services, and hospitality workers [26,27]. Although the employees are encouraged to work remotely at home full time to stay safe, this is typical only for certain types of work, on an occasional basis, or given unique employee circumstances. The employee has to do their part in reducing the fear and panic caused by the pandemic. How many employees suffered psychological stress in the company during the phase of COVID-19 pandemic? To assess the effects of the COVID-19 on the mental health of workers [28] an empirical study was conducted in the United States on a sample of 347 white collar employees to capture depression and general anxiety during COVID-19 [29]. Such surveys tend to be slower and less extensive. We focus on psychological effects of employees in companies during the phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, therefore, we need to collect the reviews of the company by employees before and after the epidemic, so that it is easy to draw out what changes have actually occurred in employees. The ways people use words online in their daily lives can also give rich information about their beliefs, fears, thinking patterns, social relationships, and personalities. This can only be collected through online social media, but not the kind of people who just want to vent their emotions or false news. Today, more than 2.9 billion people use online social media regularly [30]. In such a condition, online social media is an easy way for individuals and communities to stay connected even while physically separated.

2. Extracting Psychological Effects from Numerical Evaluations

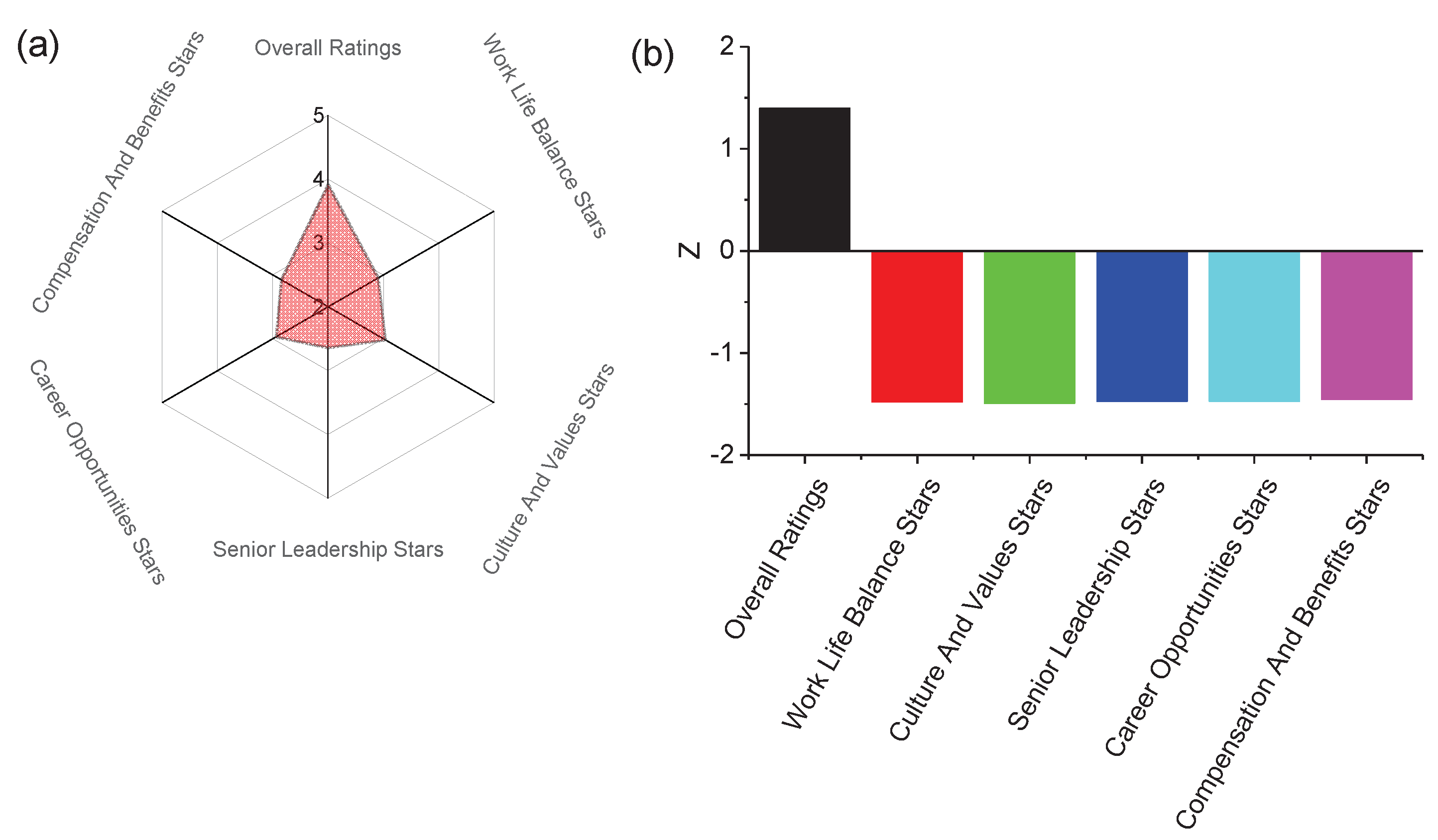

The numerical data ranging from 1 to 5 stars relate to the overall rating and the company’s five dimensions: work–life balance, culture and values, senior management, career opportunities, and salary and benefits. WResearchers first give the mean stars of overall rating and the company’s five dimensions in 2020, as shown in Figure 1a. From this wresearchers can see that the overall rating star is close to 4, while the five dimensions are all near 3. As shown in Figure 1b, wresearchers could find that in 2020, the Z-score of the overall rating is close to 1.5. The Z-score in the five aspects is actually close to −1.5. This shows that people perceive a significant improvement in the overall impression of the company after the pandemic, but they are not satisfactory for the specific aspects involved.

Figure 1. The Z-score of five dimensions of the employees, (a) the radar chart of the five dimensions of the employees in 2020 and the overall score. (b) Z-score of the five dimensions of 2020 and the overall score.

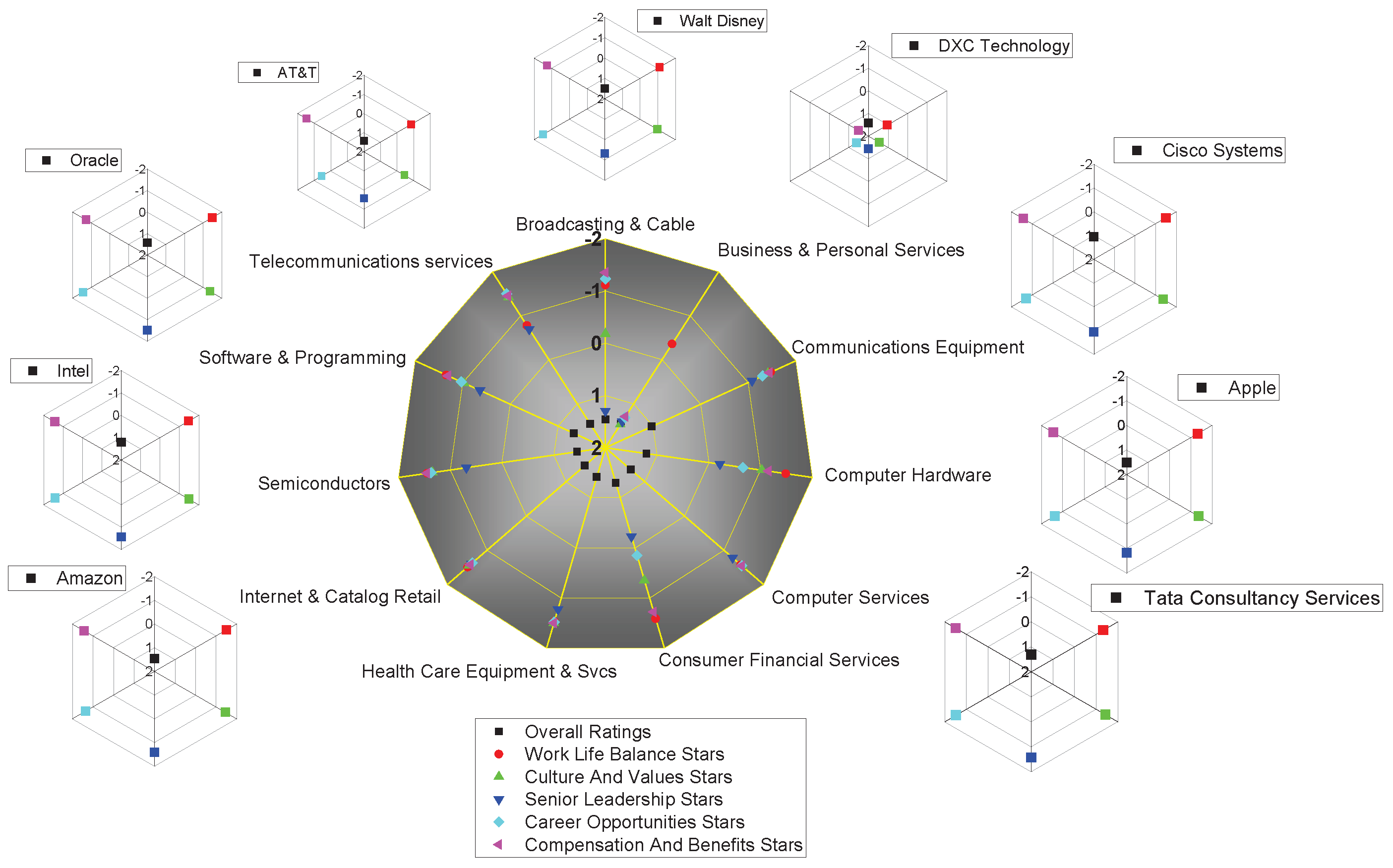

WResearchers made a statistical analysis of the overall ratings and the five dimensions of employee reviews across 11 industries and the representative companies. As shown in Figure 2, weit can be observed that the Z-score of the overall ratings in all industries is above 1. In the specific five aspects, the Z-score of work–life balance in all industries is less than −1 and negative for culture and values, but most of the industries are larger than −1. The Z-score of senior management is more scattered, for example, the Z-score of Broadcasting and Cable, Business and Personal Services is 2, whereas the Z-score of Computer Hardware and Consumer Financial Services is nearly 0. The Z-score of career opportunities is basically around −1, except that Business and Personal Services and salary and benefits are less than −1. Therefore, in general, the most affected ratings in industries are work–life balance, career opportunities, and salary and benefits, and the least affected in industries is Business and Personal Services, with a positive impact. For details, refer to the peripheral sub-graph in Figure 2, where it can be reflected from the Z-score of the five aspects of the representative companies like DXCT tech. The overall Z-scores of representative companies in other industries are all close to 2, and all five aspects are negative. In summary, impacted by COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the overall ratings of digital companies’ employees tend to be better, but the detailed five dimensions are still tending to deteriorate, except that the industry of Business and Personal Services has not been affected by the pandemic.

Figure 2. Z-score of the five aspects of the employee reviews in 11 industries corresponding to representative companies. The middle image shows the 11 industries, with different colors representing the scores of different aspects, and the peripheral image shows the employee’s reviews of the representative companies in the 11 industries.

3. Extracting Psychological Effects from the Textual Reviews

After input the textual reviews from 2017 to 2020 to the LIWC software, wresearchers then count the Z-score for 2020. We can seeIt can be seen that LIWC gives a wealth of results of psychological processes about their beliefs, fears, thinking patterns, social relationships, and personalities. Among them, the Z-score of the psychological processes, such as affective processes, biological processes, drives, and informal language, is greater than 1, but the Z-score of psychological processes, such as personal pronouns, social processes, cognitive processes, perceptual processes, and relativity, is less than −1. Concretely, in terms of personal pronouns, the number of first-person pronouns increased, while the second and third-person pronouns decreased considerably. What is more, there is a striking change in the aspect of affective processes. The Z-score of positive emotion is 1.62, and the Z-score of negative emotion is −1.62, which also indicates people’s resilience in the face of the pandemic. In terms of social processes, the Z-score is −1.64, and although Family is −0.58, Friends is 1.52. The Z-score for cognitive processes is −1.6, but for insight, the Z-score for certainty is larger than 1. For causation, discrepancy, and tentative, the Z-score is less than −1. Regarding perceptual processes, the Z-score for seeing and hearing is less than −1, however, the Z-score for sensation is greater than 1. There is little variation in biological processes, with the overall Z-score fluctuating around 1. With respect to drives, the Z-score is 1.6, where affiliation, achievement, reward, risk, etc. are greater than 1, and only power is less than −1.5. The Z-score is negative for both time orientations and relativity, and mostly less than −1. In terms of personal concerns, the Z-score of the vocabulary discussed for work is larger than 1, while that of leisure is only 0.9. Other Z-scores such as Family, Money, Religion, and Death are negative. The last aspect is Informal language. The Z-score of Swear words is −1, Fillers is 0, and others such as netspeak, assent, and nonfluencies are all greater than 0.

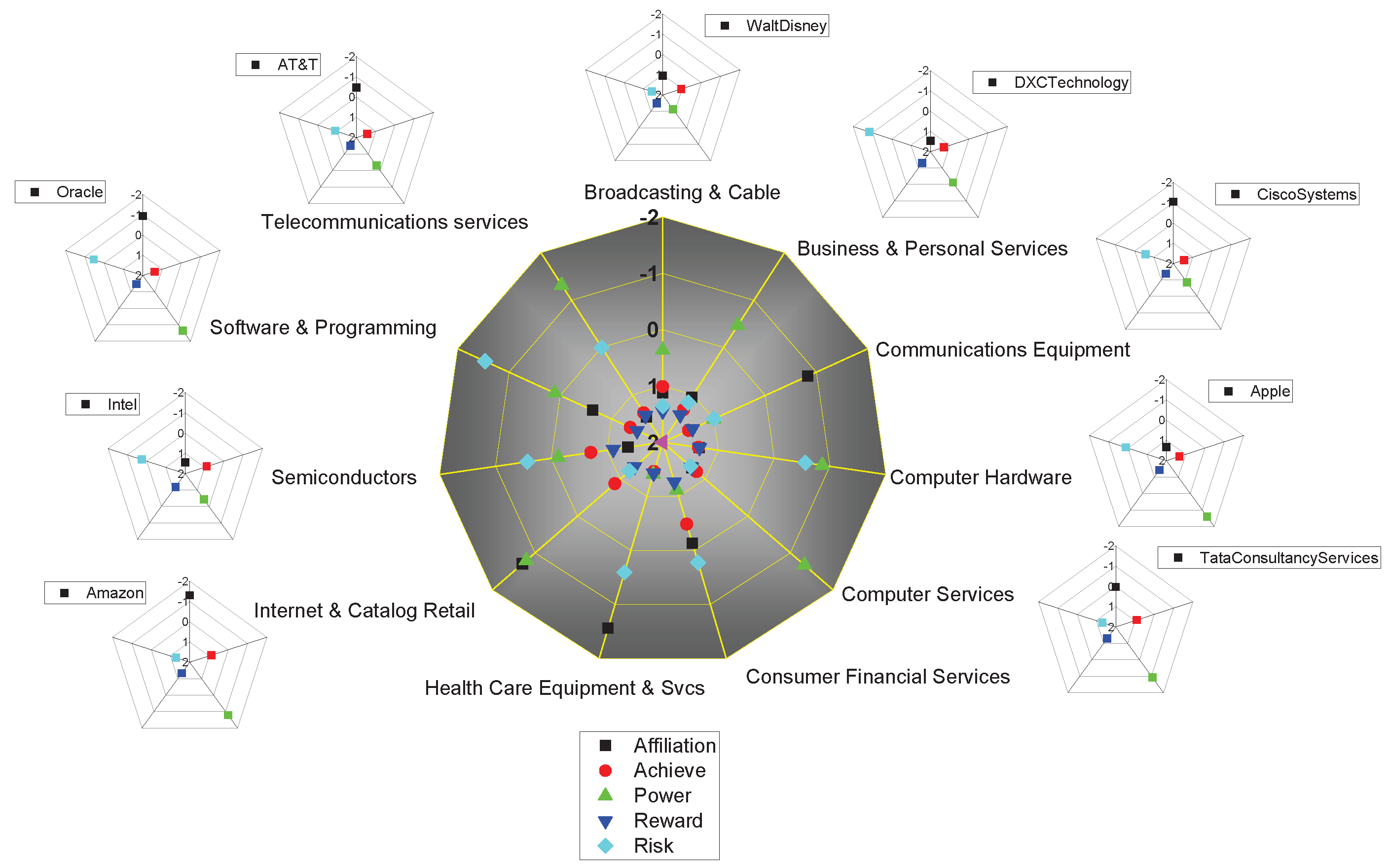

In general, the aspects of drives and personal concern are the focus of corporate employees. The psychological processes of drives involve affiliation, achievement, power, reward, and risk. The psychological processes of personal concern involve work, leisure, home, money, religion, and death. WeIt will be analyzed the two aspects of psychological processes in 11 industries and corresponding companies in Figure 3 and Figure 4. The five aspects of drives are affiliation, achievement, power, reward, and risk in 11 industries as shown in the center of Figure 3. We find that eExcept for some of the Z-scores being less than 0, most of them are greater than 0. In particular, the achievement and reward collections are greater than 1. In addition, it can be observed that the Z-cores for affiliation in Business and Personal Services, Health Care Equipment and Svcs, and Internet and Catalog Retail are less than −1. When it comes to achievement, all industries are greater than 0. Power varies across the 11 industries. Computer Hardware, Computer Services, Internet and Catalog Retail, and Telecommunications services are less than −1 for the Z-score, while it is greater than 1 for 11 industries in terms of reward. Beyond that, risk differs among the 11 industries, but most are greater than 0. Therefore, from the perspective of each representative company, there are some differences from the industry. For example, the Z-score of risk for DXCT tech is less than −1, while the Z-score of risk for Business and Personal Services, the industry to which it belongs, is greater than 1. However, most of them still maintain the affiliation, achieve, power, as can be seen in the specific performance of each company in the peripheral sub-graph of Figure 3. Each company has some challenges in drives that employees’ emotions encounter after suffering the pandemic.

Figure 3. Drives of the psychological processes in 11 industries and corresponding representative companies. The center is the Z-scores of the four aspects of drives in 11 industries. The peripheral shows the Z-scores of the four aspects of drives of a representative company.

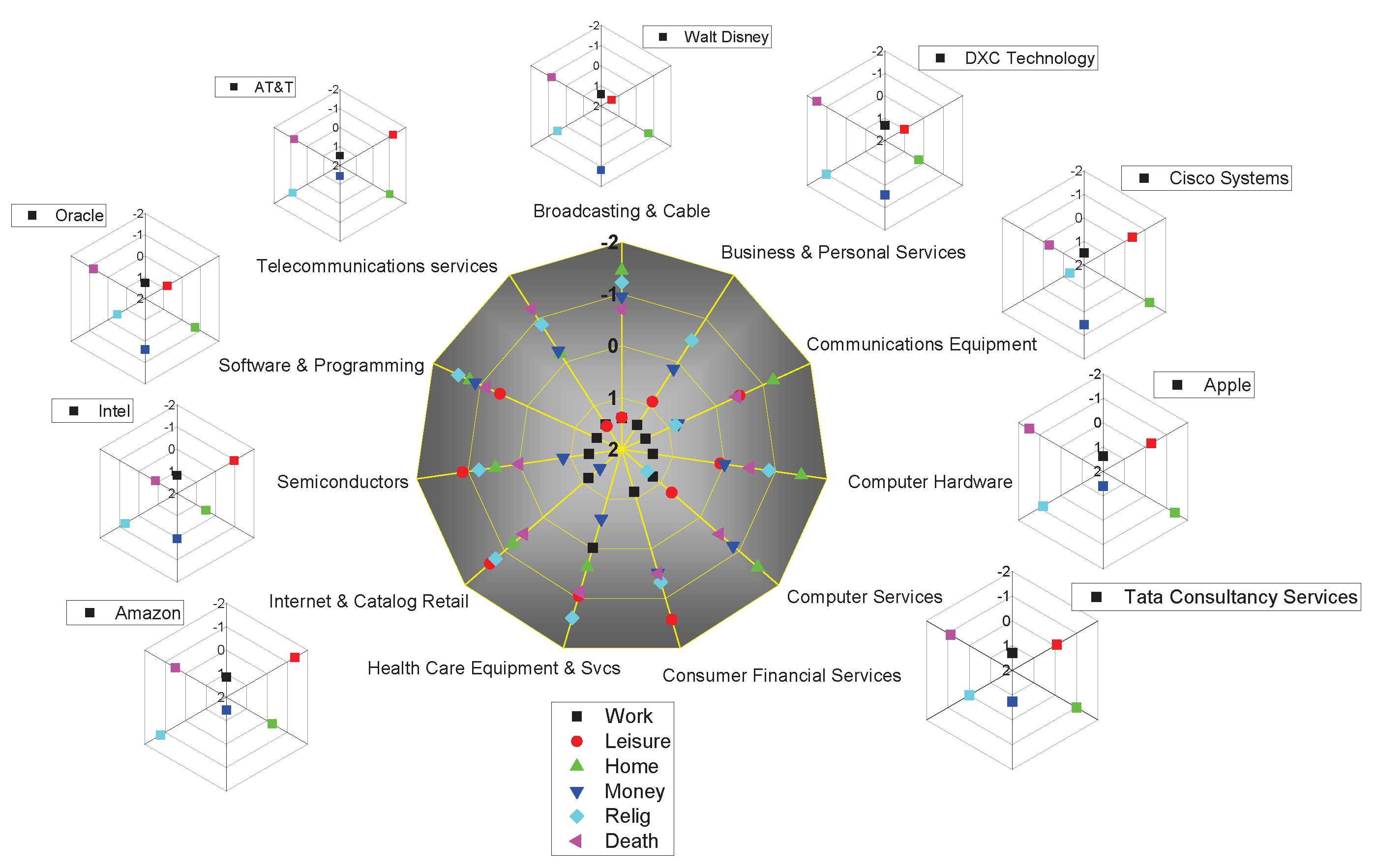

Figure 4. Personal concern of the psychological processes in 11 industries and corresponding representative companies. The center is the Z-scores of the five aspects of Drives in 11 industries. The peripheral subgraphs show the Z-scores of the five aspects of personal concern of each representative company.

Finally, it we show this shown that the psychological processes of personal concern in 11 industries and the corresponding Z-scores of representative companies as shown in Figure 4. WeIt can seebe seen the six aspects of personal concern: work, leisure, home, money, religion, death. The distribution of Z-scores is scattered. The Z-score of the work is greater than 1, leaving only Health Care Equipment and Svcs with a Z-score of 0. The Z-scores for leisure, money, religion, and death vary across industries. The Z-score on the term of home is basically around −1, indicating that there are fewer expressions for this aspect of home after the pandemic than before the pandemic. The peripheral subgraphs of Figure 4 also show the Z-scores for 6 aspects of the personal concern for representative subsidiaries in 11 industries. Here weit can be observed the changes before and after the pandemic of a specific company, especially the changes in these prominent top digital companies. Therefore, irrespective of the statistics of drives or personal concerns, we are able to oit can be observed some positive changes before and after the pandemic. For example, the achievement is good, but the aspect of home is deteriorating. For different companies in different industries there are some commonalities and differences, and these should be emphatically considered when caring for the employees of the company.

References

- Wu, T.C.; Jia, X.Q.; Shi, H.F.; Niu, J.Q.; Yin, X.H.; Xie, J.L.; Wang, X.L. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 91–98.

- Maykrantz, S.A.; Nobiling, B.D.; Oxarart, R.A.; Langlinais, L.A.; Houghton, J.D. Coping with the crisis: The effects of psychological capital and coping behaviors on perceived stress. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2021, 14, 650–665.

- Lee, H. Changes in workplace practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of emotion, psychological safety and organisation support. J. Organ. Eff.-People Perform. 2021, 8, 97–128.

- Radhakrishnan, B.L.; Kirubakaran, E.; Belfin, R.V.; Selvam, S.; Sagayam, K.M.; Elngar, A.A. Mental health issues and sleep quality of Indian employees and higher education students during COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Inform. 2021, 9, 193–210.

- Deng, J.W.; Zhou, F.W.; Hou, W.T.; Silver, Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Huang, E.M.; Zuo, Q.K. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1486, 90–111.

- Dagnino, P.; Anguita, V.; Escobar, K.; Cifuentes, S. Psychological Effects of Social Isolation Due to Quarantine in Chile: An Exploratory Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1232.

- Anicich, E.M.; Foulk, T.A.; Osborne, M.R.; Gale, J.; Schaerer, M. Getting Back to the “New Normal”: Autonomy Restoration During a Global Pandemic. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 931–943.

- Talevi, D.; Socci, V.; Carai, M.; Carnaghi, G.; Faleri, S.; Trebbi, E.; di Bernardo, A.; Capelli, F.; Pacitti, F. Mental health outcomes of the CoVID-19 pandemic. Riv. Psichiatr. 2020, 55, 137–144.

- Ardebili, M.E.; Naserbakht, M.; Bernstein, C.; Alazmani-Noodeh, F.; Hakimi, H.; Ranjbar, H. Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 547–554.

- Kazgan, A.; Yildiz, S.; Kurt, O. The relationship between hope in healthcare employees and social support and coping ability during the outbreak process. Ann. Clin. Anal. Med. 2021, 12, 377–383.

- Arpacioglu, M.S.; Baltaci, Z.; Unubol, B. Burnout, fear of Covid, depression, occupational satisfaction levels and related factors in healthcare professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic. Cukurova Med. J. 2021, 46, 88–100.

- Du, Y.X.; Liu, H. Analysis of the Influence of Psychological Contract on Employee Safety Behaviors against COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6747.

- Bahar, A.; Kocak, H.S.; Baglama, S.S.; Cuhadar, D. Can Psychological Resilience Protect the Mental Health of Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period? Dubai Med. J. 2020, 3, 133–139.

- Akman, C.; Cetin, M.; Toraman, C. The analysis of emergency medicine professionals’ occupational anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Signa Vitae 2021, 17, 103–111.

- Tengilimoglu, D.; Zekioglu, A.; Tosun, N.; Isik, O.; Tengilimoglu, O. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic period on depression, anxiety and stress levels of the healthcare employees in Turkey. Leg. Med. 2021, 48, 101811.

- Bernardino, E.; Nascimento, J.D.d.; Raboni, S.M.; Sousa, S.M.d. Care management in coping with COVID-19 at a teaching hospital. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20200970.

- Lohana, S.; Zaidi, N.H.; Zaidi, T.H.; Saahil, K.; Novlani, K. Psychological impact of Corona Virus Disease on genera population in Karachi. World Fam. Med. 2021, 19, 59–70.

- Golden, E.A.; Zweig, M.; Danieletto, M.; Landell, K.; Nadkarni, G.; Bottinger, E.; Katz, L.; Somarriba, R.; Sharma, V.; Katz, C.L.; et al. A Resilience-Building App to Support the Mental Health of Health Care Workers in the COVID-19 Era: Design Process, Distribution, and Evaluation. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e26590.

- Blake, H.; Bermingham, F.; Johnson, G.; Tabner, A. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2997.

- Akyol, P.K. Museum Activities During and After the Covid-19 Pandemic. Milli Folk. 2020, 2020, 72–86.

- Andel, S.A.; Shen, W.; Arvan, M.L. Depending on Your Own Kindness: The Moderating Role of Self-Compassion on the Within-Person Consequences of Work Loneliness During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 276–290.

- Wu, X.Y.; Lin, L.; Wang, J. When does breach not lead to violation? A dual perspective of psychological contract in hotels in times of crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102887.

- Pathak, D.; Joshi, G. Impact of psychological capital and life satisfaction on organizational resilience during COVID-19: Indian tourism insights. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2398–2415.

- Yorulmaz, M.; Sevinc, F. Supervisor support and turnover intentions of yacht captains: The role of work-family conflict and psychological resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1554–1570.

- Como, R.; Hambley, L.; Domene, J. An Exploration of Work-Life Wellness and Remote Work During and Beyond COVID-19. Can. J. Career Dev. 2020, 20, 46–56.

More