You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Dean Liu and Version 1 by Francois Philippart.

Advance directives (ADs) allow everyone to give their preferences in advance regarding life sustaining treatments, continuation, and withdrawal or withholding of treatments in case one is not able to speak their mind anymore. While the absence of ADs is associated with a greater probability of receiving unwanted intensive care around the end of their life, their existence correlates with the respect of the patient’s desires and their greater satisfaction.

- end of life

- advance directives

- advance care planning

- intensive care

1. Introduction

In several studies around the world, patients reported a strong interest for advance directives (AD) or ACP [21,22,23,24,25][1][2][3][4][5]. Nonetheless, the percentage of people who effectively have AD remains very low in the general population [26,27][6][7]. It scarcely exceeds 50% of oncology or hematology patients in some North American reports [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] and has been estimated to be as little as 5% in other [36][16].

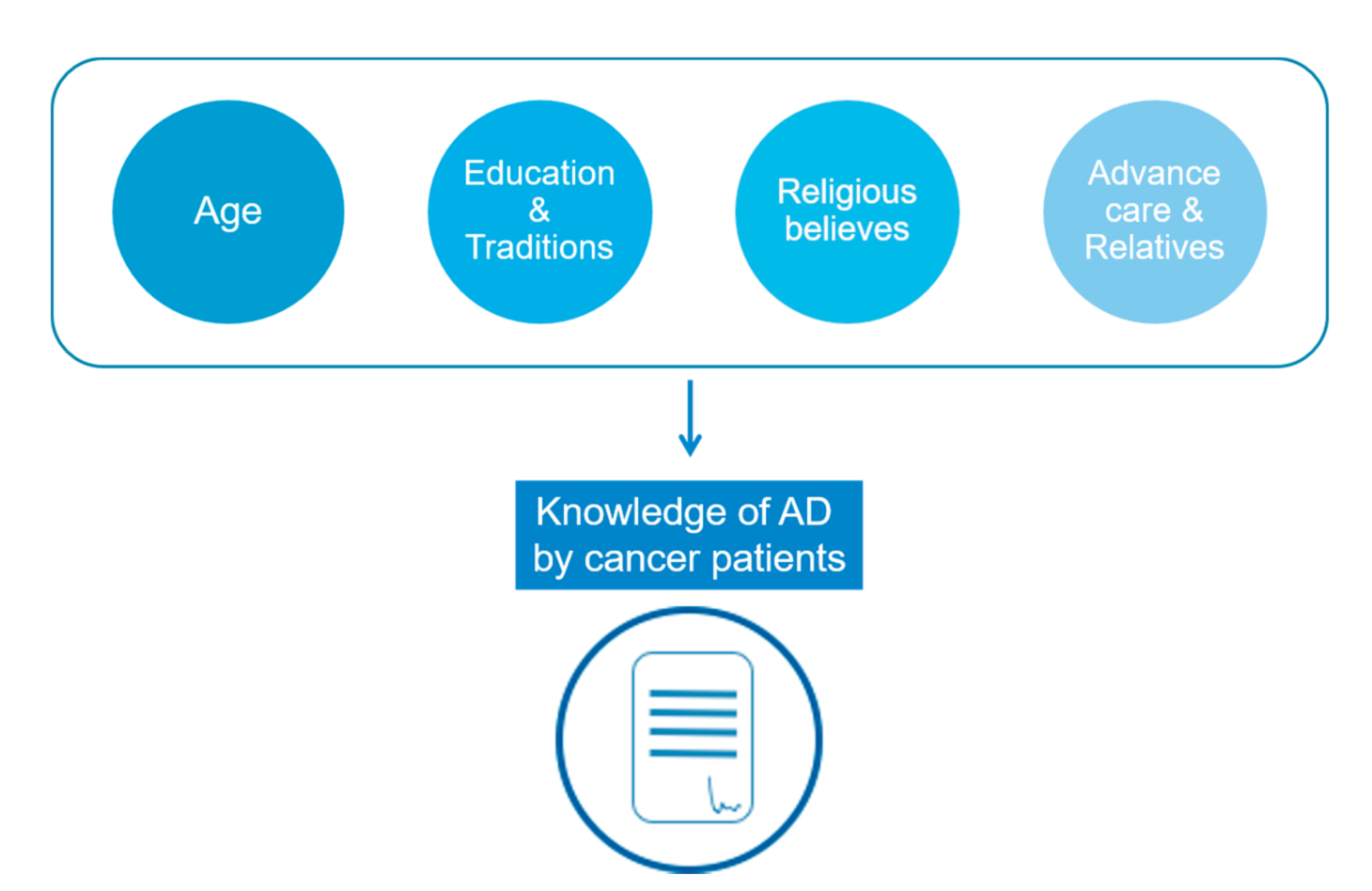

Figure 1.

Main obstacles for advance directives information and use in cancer patients.

2. AD to Relieve Relatives

Family plays a central role both during the process of writing AD and at the time of end-of-life decisions [53][17]. In an American study of 2008, 73% of Latinos discussed ACP with their family but only 37% with their doctor [40][18]. They argued that writing ACP relieves their loved ones from making difficult decisions. Indeed, in the absence of AD, guilt or regret may push families to choose life-sustaining treatments over palliative care, no matter how aggressive and ineffective those treatments would be.

3. Awareness of AD

Lack of awareness regarding AD by patients is obviously a major obstacle. It ranges from complete ignorance of their existence or their usefulness, to redaction difficulties due to a lack of knowledge regarding their practical use or how to implement them.

Six years after AD’s legal apparition, a French survey including 367 hospitalized patients revealed that only 34.8% of them were aware of the possibility to have some [21][1]. However, after proper information, 93% of the patients were in favour of AD, suggesting that better communication could increase AD’s drafting. The urge to solve this issue is underlined in McDonald’s study where cancer patients themselves reported the lack of knowledge to be the strongest barrier to writing AD [28][8]. In Hubert’s study, the need for more information was the reason why half the patients had not written their AD [34][14]. To raise awareness on AD and promote discussion with physicians or relatives, question prompt lists on end-of-life care seem to be efficient [54,55][20][21].

People may also have trouble figuring out how their AD can specifically relate to their disease. In a survey conducted in Germany in 2014, half of the patients were in favour of AD consultations. However, only 20% reported that their interest for those consultations was associated with their cancer diagnosis whereas the link between a severe chronic disease and the benefit of expressing themselves about their preferences concerning therapeutic intervention in case of acute and critical situation remains seems not to be obvious [56][22]. This work underlines the necessity to properly inform patients and physicians on the role and use of AD, and why a new serious disease may be a good time to think about one’s wishes for his care.

4. Sickness

Suffering from a deadly disease compels patients to think about their end of life. Unsurprisingly, a new diagnosis of cancer and duration of the illness turn out to be favouring factors towards AD’s writing [22,30,56][2][10][22].4.1. The Importance of Prognosis

Both the ongoing disease and the patient’s past history play a role in the perception of AD. Sahm et al. noted in 2005 that patients having a previous experience of serious illness increasingly reported their intention to write AD [23][3]. In the same cohort, patients who often experienced pain as well as those deeming to be in a bad state of health state also reported more frequently their intention to draft AD [23][3].

Realizing the severity of one’s condition seems to be a trigger to AD’s drafting [51][23]. A longer self-assessed life-expectancy is associated with a lower likelihood of do-not-resuscitate order and a higher preference for life-prolonging over comfort-oriented care [57][24]. In a study including people without written AD, the proportion of patients in favour of a specific consultation on AD doubled between those with a non-malignant disease and those with a malignant disease and a life expectancy shorter than 6 months [56][22]. Similar observations were made with curative treatments: patients who wrongly overestimated their survival rate were far more likely to favour life sustaining therapies care [58,59][25][26].

However, even when prognosis is discussed with patients, it may not be well understood. A multicentre study including nearly six hundred metastatic cancer patients, revealed that even when informed of their prognosis by their physician, nearly a third of patients overestimated their life expectancy by more than 2 years. Correct recall of prognostic disclosure was associated with a more realistic assessment of their life expectancy [57][24].

4.2. Mental Stunning

When information about the disease, its treatment and its prognosis is delivered during the cancer clinic visit, patients may be stunned, impairing their ability to process and understand those details [60][27]. Some may be concerned about the psychological repercussions for the patient of the announcement of a pejorative prognosis right after being informed of their diagnosis. However, George et al. found no lasting psychological harm amongst terminally ill patients after they understood their prognosis [61][28]. Addressing these psychological factors may help patients better understand the ins and outs of their care and therefore choose the most appropriate care [60][27].

4.3. Link between End-of-Life Care and Anticipated Discussion

Encouraging early communication between physicians and patients regarding the prognosis of the disease could help patients to better prepare for possible complications or tragic outcomes, and to refine their goal of care [62][29]. Many papers showed that patients who discussed their end-of-life preferences early in the history of their illness with their physicians were more likely to report a greater well-being, and to receive fewer aggressive interventions in their last weeks of life, without survival time reduction [63,64,65][30][31][32].

Ganti et al. retrospectively explored the relation between engagement in ACP amongst patients receiving a hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) and adverse outcomes, as well as overall survival. They found that patients who engaged in ACP before HSCT had a better one-year and overall survival compared with patients without ACP [30][10]. Though no direct causal relation could be suspected, it is possible that those who did not engage in ACP were less prepared to face complications when they occur.

References

- Guyon, G.; Garbacz, L.; Baumann, A.; Bohl, E.; Maheut-Bosser, A.; Coudane, H.; Kanny, G.; Gillois, P.; Claudot, F. Trusted person and living will: Information and implementation defect. Rev. Med. Interne 2014, 35, 643–648.

- Zhang, Q.; Xie, C.; Xie, S.; Liu, Q. The Attitudes of Chinese Cancer Patients and Family Caregivers toward Advance Directives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 816.

- Sahm, S.; Will, R.; Hommel, G. Attitudes towards and Barriers to Writing Advance Directives amongst Cancer Patients, Healthy Controls, and Medical Staff. J. Med. Ethics 2005, 31, 437–440.

- Dow, L.A.; Matsuyama, R.K.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Kuhn, L.; Lamont, E.B.; Lyckholm, L.; Smith, T.J. Paradoxes in Advance Care Planning: The Complex Relationship of Oncology Patients, Their Physicians, and Advance Medical Directives. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 299–304.

- Mercadante, S.; Costanzi, A.; Marchetti, P.; Casuccio, A. Attitudes among Patients with Advanced Cancer toward Euthanasia and Living Wills. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, e3–e6.

- De Vleminck, A.; Pardon, K.; Houttekier, D.; Van den Block, L.; Vander Stichele, R.; Deliens, L. The Prevalence in the General Population of Advance Directives on Euthanasia and Discussion of End-of-Life Wishes: A Nationwide Survey. BMC Palliat. Care 2015, 14, 71.

- Pennec, S.; Monnier, A.; Pontone, S.; Aubry, R. End-of-Life Medical Decisions in France: A Death Certificate Follow-up Survey 5 Years after the 2005 Act of Parliament on Patients’ Rights and End of Life. BMC Palliat. Care 2012, 11, 25.

- McDonald, J.C.; du Manoir, J.M.; Kevork, N.; Le, L.W.; Zimmermann, C. Advance Directives in Patients with Advanced Cancer Receiving Active Treatment: Attitudes, Prevalence, and Barriers. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 523–531.

- Obel, J.; Brockstein, B.; Marschke, M.; Robicsek, A.; Konchak, C.; Sefa, M.; Ziomek, N.; Benfield, T.; Peterson, C.; Gustafson, C.; et al. Outpatient Advance Care Planning for Patients with Metastatic Cancer: A Pilot Quality Improvement Initiative. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 1231–1237.

- Ganti, A.K.; Lee, S.J.; Vose, J.M.; Devetten, M.P.; Bociek, R.G.; Armitage, J.O.; Bierman, P.J.; Maness, L.J.; Reed, E.C.; Loberiza, F.R. Outcomes after Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies in Patients with or without Advance Care Planning. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 5643–5648.

- Tan, T.S.; Jatoi, A. An Update on Advance Directives in the Medical Record: Findings from 1186 Consecutive Patients with Unresectable Exocrine Pancreas Cancer. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2008, 39, 100–103.

- Ho, G.W.K.; Skaggs, L.; Yenokyan, G.; Kellogg, A.; Johnson, J.A.; Lee, M.C.; Heinze, K.; Hughes, M.T.; Sulmasy, D.P.; Kub, J.; et al. Patient and Caregiver Characteristics Related to Completion of Advance Directives in Terminally Ill Patients. Palliat. Support. Care 2017, 15, 12–19.

- Clark, M.A.; Ott, M.; Rogers, M.L.; Politi, M.C.; Miller, S.C.; Moynihan, L.; Robison, K.; Stuckey, A.; Dizon, D. Advance Care Planning as a Shared Endeavor: Completion of ACP Documents in a Multidisciplinary Cancer Program. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 67–73.

- Hubert, E.; Schulte, N.; Belle, S.; Gerhardt, A.; Merx, K.; Hofmann, W.-K.; Stein, A.; Burkholder, I.; Hofheinz, R.-D.; Kripp, M. Cancer Patients and Advance Directives: A Survey of Patients in a Hematology and Oncology Outpatient Clinic. Onkologie 2013, 36, 398–402.

- Ha, F.J.; Weickhardt, A.J.; Parakh, S.; Vincent, A.D.; Glassford, N.J.; Warrillow, S.; Jones, D. Survival and Functional Outcomes of Patients with Metastatic Solid Organ Cancer Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit of a Tertiary Centre. Crit. Care Resusc. 2017, 19, 159–166.

- Roger, C.; Morel, J.; Molinari, N.; Orban, J.C.; Jung, B.; Futier, E.; Desebbe, O.; Friggeri, A.; Silva, S.; Bouzat, P.; et al. Practices of End-of-Life Decisions in 66 Southern French ICUs 4 Years after an Official Legal Framework: A 1-Day Audit. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2015, 34, 73–77.

- Puchalski, C.M.; Zhong, Z.; Jacobs, M.M.; Fox, E.; Lynn, J.; Harrold, J.; Galanos, A.; Phillips, R.S.; Califf, R.; Teno, J.M. Patients Who Want Their Family and Physician to Make Resuscitation Decisions for Them: Observations from SUPPORT and HELP. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Hospitalized Elderly Longitudinal Project. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000, 48, S84-90.

- Sudore, R.L.; Lum, H.D.; You, J.J.; Hanson, L.C.; Meier, D.E.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Matlock, D.D.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Korfage, I.J.; Ritchie, C.S.; et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition from a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017.

- Alano, G.J.; Pekmezaris, R.; Tai, J.Y.; Hussain, M.J.; Jeune, J.; Louis, B.; El-Kass, G.; Ashraf, M.S.; Reddy, R.; Lesser, M.; et al. Factors Influencing Older Adults to Complete Advance Directives. Palliat. Support. Care 2010, 8, 267–275.

- Clayton, J.M.; Butow, P.N.; Tattersall, M.H.N.; Devine, R.J.; Simpson, J.M.; Aggarwal, G.; Clark, K.J.; Currow, D.C.; Elliott, L.M.; Lacey, J.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Prompt List to Help Advanced Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers to Ask Questions about Prognosis and End-of-Life Care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 715–723.

- Dimoska, A.; Tattersall, M.H.N.; Butow, P.N.; Shepherd, H.; Kinnersley, P. Can a “Prompt List” Empower Cancer Patients to Ask Relevant Questions? Cancer 2008, 113, 225–237.

- Pfirstinger, J.; Kattner, D.; Edinger, M.; Andreesen, R.; Vogelhuber, M. The Impact of a Tumor Diagnosis on Patients’ Attitudes toward Advance Directives. Oncology 2014, 87, 246–256.

- Wong, S.Y.; Lo, S.H.; Chan, C.H.; Chui, H.S.; Sze, W.K.; Tung, Y. Is It Feasible to Discuss an Advance Directive with a Chinese Patient with Advanced Malignancy? A Prospective Cohort Study. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012, 18, 178–185.

- Enzinger, A.C.; Zhang, B.; Schrag, D.; Prigerson, H.G. Outcomes of Prognostic Disclosure: Associations with Prognostic Understanding, Distress, and Relationship with Physician among Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3809–3816.

- Weeks, J.C.; Cook, E.F.; O’Day, S.J.; Peterson, L.M.; Wenger, N.; Reding, D.; Harrell, F.E.; Kussin, P.; Dawson, N.V.; Connors, A.F.; et al. Relationship between Cancer Patients’ Predictions of Prognosis and Their Treatment Preferences. JAMA 1998, 279, 1709–1714.

- Sborov, K.; Giaretta, S.; Koong, A.; Aggarwal, S.; Aslakson, R.; Gensheimer, M.F.; Chang, D.T.; Pollom, E.L. Impact of Accuracy of Survival Predictions on Quality of End-of-Life Care Among Patients with Metastatic Cancer Who Receive Radiation Therapy. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, e262–e270.

- Derry, H.M.; Reid, M.C.; Prigerson, H.G. Advanced Cancer Patients’ Understanding of Prognostic Information: Applying Insights from Psychological Research. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4081–4088.

- George, L.S.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Epstein, A.S.; Shen, M.; Prigerson, H.G. Advanced Cancer Patients’ Changes in Accurate Prognostic Understanding and Their Psychological Well-Being. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 983–989.

- Yoo, S.H.; Lee, J.; Kang, J.H.; Maeng, C.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Song, E.-K.; Koh, Y.; Yun, H.-J.; Shim, H.-J.; Kwon, J.H.; et al. Association of Illness Understanding with Advance Care Planning and End-of-Life Care Preferences for Advanced Cancer Patients and Their Family Members. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2959–2967.

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742.

- Greer, J.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Jackson, V.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Lennes, I.T.; Heist, R.S.; Gallagher, E.R.; Temel, J.S. Effect of Early Palliative Care on Chemotherapy Use and End-of-Life Care in Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO 2011, 30, 394–400.

- Wright, A.A.; Zhang, B.; Ray, A.; Mack, J.W.; Trice, E.; Balboni, T.; Mitchell, S.L.; Jackson, V.A.; Block, S.D.; Maciejewski, P.K.; et al. Associations between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. JAMA 2008, 300, 1665–1673.

More