Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a highly aggressive cancer with poor prognosis, as the clinical symptoms of this disease are only presented at an advanced stage. At a global level, the incidence of PDAC is expected to continue increasing as observed by the trend in the past consecutive years. On the other hand, the available US Food and Drug Administration-approved biomarker for PDAC, CA 19-9, is not reliable for diagnostic purposes but is rather useful for monitoring treatment response among PDAC patients. Nevertheless, there is an urgent need to identify reliable biomarkers for both diagnosis (specifically for the early detection) and ascertain prognosis, as well as to monitor treatment response and tumour recurrence of PDAC. In recent years, proteomic technologies have grown exponentially at an accelerated rate for a wide range of applications in cancer research. Interestingly, myriad of research mainly focused on the identification of potential biomarkers for the use of early detection and/or diagnosis of PDAC. Nonetheless, it is unfortunate that several other studies too have concurrently reported that these ‘identified potential biomarkers’ either as lacking in specificity and/or has prognostic values, instead. Likewise, studies conducted on biomarkers to ascertain the prognosis of PDAC, as well as to monitor treatment response and predict tumour recurrence in PDAC had also evidently shown conflicting results. In view of this, the identification and/or implementation of protein-based biomarkers with improved specificity and sensitivity for clinical utility for PDAC remains much to be desired. On the bright side though, the integration of multi-omics techniques, as well as further research on other novel technologies such as nanoparticle-enabled blood test and artificial intelligence), is hoped to lead to the discovery of superior biomarkers for PDAC that could be implemented into clinical practice in the near future.

- pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- biomarkers

- CA 19-9

- proteomics

- diagnosis

- prognosis

- monitoring treatment response

- tumour recurrence

1. Introduction

| Target * | Name | Clinical Utility | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNAs | K-ras | mutation | Diagnosis | [23] | |

| Methylated | ADAMTS1 | and | BNC1 | Early diagnosis | [24] |

| TP53 | mutation | Prognosis | [25] | ||

| Mutations of | BRCA2, EGFR, ERBB2 | and | KDR | Monitoring treatment response | [26] |

| Peritoneal lavage tumour DNA | Prognosis/Monitoring tumour recurrence | [27] | |||

| mRNAs | WASF2 | mRNA | Early diagnosis | [28] | |

| EVL | mRNA | Prognosis | [29] | ||

| FAM64A | mRNA | Prognosis | [30] | ||

| MicroRNAs (miR) | [31] | ** | miR-181c miR-210 |

Diagnosis | [32] |

| miR-10b miR-155 miR-216 |

Prognosis | [33] | |||

| miR-196a | Prognosis | [34] | |||

| miR-21 | Diagnosis/Prognosis/Monitoring treatment response | [32][35][36] | |||

| miR-155 | Monitoring treatment response | [37] | |||

| miR-142-5p miR-506 miR-509-5p miR-1243 |

Monitoring treatment response | [36] | |||

| miR-451a | Prognosis/Monitoring tumour recurrence | [38] | |||

| Long noncoding RNAs | SNHG15 | Early diagnosis | [39] | ||

| HOTAIR | MALAT-1 | Prognosis | [40] | ||

| LINC00460 | Prognosis | [41] | |||

| PVT1 | Monitoring treatment response | [42] | |||

| Circulating tumour cells | Diagnosis | [43] | |||

| Prognosis | [44] | ||||

| Vimentin (surface marker) | Monitoring treatment response | [45] | |||

| Monitoring tumour recurrence | [46] | ||||

| Metabolites | Panel of acetylspermidine, diacetylspermine, indole-derivative and two lysophosphatidylcholines | Early diagnosis | [47] | ||

| Polyamines | Diagnosis | [48] | |||

| Ethanolamine | Prognosis | [49] | |||

| Lactic acid L-Pyroglutamic acid |

Monitoring treatment response | [50] | |||

| Carbohydrates (glycan) | Alpha-2,6-linked sialylation and fucosylation of tri- and tetra-antennary | N | -glycans | Diagnosis | [51] |

| N | -glycan branching: alpha-1,6-mannosylglycoprotein 6-beta- | N | -acetylglucosaminyltransferase A | Early diagnosis | [52] |

| β | 1,3- | N | -acetylglucosaminyltransferase 6 | Prognosis | [53] |

| Hyaluronan | Monitoring treatment response | [54] |

ADAMTS1—A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1; BNC1—zinc finger protein basonuclin-1; BRCA2—Breast cancer susceptibility gene-2; EGFR—Epidermal growth factor receptor; ERBB2—Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2; EVL—Ena/VASP-like; FAM64—Family with sequence similarity 64 member A; HOTAIR—HOX transcript antisense RNA; KDR—Kinase insert domain receptor; KRAS—Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; LINC00460—Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 460; LDLRAD3—Low density lipoprotein receptor class A domain containing 3; MALAT-1—Metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; PVT1—Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1; RNU2-1—RNA U2 small nuclear 1; SNHG15—Small nucleolar RNA host gene 15; WASF-2—Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein family member 2. * Recently identified protein-based biomarkers for PDAC will be discussed in the subsequent section of this review. ** This has been previously extensively reviewed by Tesfaye et al. (2019).

1.1. PDAC: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Staging and Treatment

1.2. FDA-Approved Biomarkers for PDAC

2. Proteomics-Based PDAC Research: Techniques, Samples, and Samples Processing

3. Biomarker Investigations

Biomarkers for Early Detection and/or Diagnosis of PDAC

Previous research has indeed reported that a single biomarker, such as CA 19-9 alone is unable to provide a reliable diagnosis that is sensitive and specific for PDAC [160]. As deduced based on a few studies below, biomarker panels that combine a few markers appear effective and enhance the accuracy of PDAC diagnosis. For this, Jisook Park et al. [161] and Jiyoung Park et al. [162] had also demonstrated improved cancer discerning capabilities of the identified respective panels of proteins when used in combination with CA 19-9, thus concurring with the previous hypothesis of having multi-markers for complex diseases such as cancer rather than just a single biomarker [163]. Here, Jisook Park et al. first identified the promising candidate biomarkers through shotgun proteomics and pathway-based gene expression meta-analysis, then further validated the selected nine protein candidates via stable isotope dilution (SID)-MRM-MS and immunohistochemistry [161]. Based on the results, apolipoprotein A-IV (APOA4), apolipoprotein C-III, IGFBP2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) were found significantly altered in the serum of PDAC patients (stage I–IV) compared to those with pancreatitis as well as healthy controls. These are acute-phase proteins and are strongly associated with cancer and its development [164] and hence, has been previously suggested as potential biomarkers [165]. For instance, acute phase proteins including α1-antitrypsin, α1-antichymotrypsin (ACT), complement factor B (CFB) and leucine-rich glycoprotein (LRG) proteins were previously reported to be enhanced in PanC, while upregulated levels of ACT, CFB and clusterin as well as decreased levels of kininogen in patients with breast cancer [165]. By comparing the diagnostic performances of these four different proteins in combination with CA 19-9, the researchers then proceeded to generate a biomarker panel consisting of APOA4, TIMP1 and CA 19-9 that showed better performance in distinguishing early stage PDAC (stage I and II) from those with pancreatitis (90% specificity and 85.5% sensitivity).

Following an extensive database and literature search and review of over 1000 candidate markers, Jiyoung Park et al. refined and selected two candidate proteins consisting of leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein (LRG1) and transthyretin (TTR) in combination with CA19-9 for validation using MRM-MS on more than 1000 plasma samples [162]. The performances of the panel were evaluated in various conditions: PDAC stage I and II vs. healthy controls, PDAC vs. benign pancreatic disease and other cancers individually. Overall, it was observed that the biomarker panel had a sensitivity of 82.5% and a specificity of 92.1%. To further establish this biomarker panel, the researchers then developed an automated multi-marker ELISA kit using the three proteins for the diagnosis of PDAC and observed enhanced levels of specificity at 90.69% and sensitivity at 92.05%. Nonetheless, the inclusion of TTR as a biomarker is rather conflicting considering another report which has demonstrated higher levels of TTR in the sera of patients with PDAC compared to controls but using 2D-DIGE, MALDI-ToF-MS and validation via ELISA [166].

Serological proteome analysis (SERPA), also known as 2D western blot analysis, is a technique used to identify tumour antigens by first fractionating the cell lysates with 2D gels followed by transfer of the proteins onto a membrane and probing with serum [167]. By using SERPA, 18 immunoreactive antigens were identified in serum via 2-DE and MALDI-ToF-MS. These include ATP synthase, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH), laminin, phosphoglycerate mutase B (PGAM-B), Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor II (RhoGDI2), septin, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and tubulin β8 channel, all of which were found strongly associated with the pathogenesis of PDAC [168]. Here, the researchers discussed the roles of different types of immunoreactive proteins such as cytoskeletal proteins (e.g., laminin, septin and tubulin β) and metabolic reprogramming-associated proteins (e.g., GAPDH, PGAM-B, RhoGDI2 and SOD) in cancer. Nonetheless, some of these proteins are additionally regarded as general proteins that take part in key processes in the cell, therefore, the real mechanism with which these proteins are associated with the diagnosis of PDAC remains unknown.

To date, most of the biomarker studies on PDAC are typically based on serum/plasma and tissue analysis. Only quite recently, a few publications have highlighted the potential of urine as an interesting biological sample for biomarker investigations in PDAC have emerged. For instance, Radon et al. analysed the proteome of urine samples obtained from PDAC and chronic pancreatitis patients, as well as healthy controls using NPLC-MS/MS [169]. They identified a candidate biomarker panel consisting of lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1), regenerating family member 1 alpha (REG1A) and trefoil factor 1 (TFF1). Following this, since there were several studies [170,171,172,173] that have proposed REG1A as well as REG1B from various biological samples such as serum, urine, tissues and pancreatic ductal fluid as candidate biomarkers, five years later, the same group of researchers replaced REG1A with REG1B for the validation of the biomarker panel using ELISA [113]. They then compared the performance of this newer protein panel with the previous study and found that the urinary REG1B levels (AUC value: 0.93) outperformed REG1A (AUC value: 0.90) in discriminating early stage PDAC (stage I and II) from the healthy controls as well as chronic pancreatitis patients. Concurring with this finding, Li et al. also showed an increased expression of REG1A but in tissues of PanIN lesions as they progress to PDAC, while the expression of REG1B remained elevated only in the early stage of PanIN lesions, thus highlighting REG1B as a better choice for use as a diagnostic biomarker [170]. In addition, Li et al. reported that although the serum levels of both REG1A and REG1B were significantly higher in PDAC patients compared to healthy controls, there was also an insignificant elevation of these proteins in chronic pancreatitis patients as compared to healthy controls [170]. When both studies [113,170] were compared in this context, it highly indicated a differential expression of these proteins in the different types of biological samples. On a different note, Li et al. reported a prognostic behaviour of these proteins as such that the expression of these proteins was seen to gradually reduce as the tumour progresses from well differentiated to poorly differentiated [170]. This finding certainly contradicts the study of Debernadi et al. on the potential of REG proteins as diagnostic biomarkers for PDAC [113].

Biomarkers for Determining Prognosis of PDAC

The prediction of prognosis is important in determining the likely health outcome of cancer patients (e.g., overall survival, disease recurrence). For this, Kuwae and colleagues attempted to identify a biomarker with prognostic potential by analysing the proteomes of tumours and adjacently located non-tumour pancreatic tissues of the same patient using iTRAQ labelling and NPLC-MS/MS [175]. In this study, the researchers utilised Zwittergent-based buffer for the extraction of proteins from the formalin-fixation and paraffin-embedded tumour tissues for LC-MS/MS analysis. In line with this, a study by Shen et al. comparing the different extraction buffers for downstream proteomic analysis of tissue samples deduced that Zwittergent was the most effective and efficient for protein extraction in these sample types [176]. Here, the elevated levels of paraneoplastic Ma antigen–like 1 (PNMAL1) was found in tumour tissues but only in trace amounts in the adjacent non-tumour tissues. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry analyses revealed that positive expression of PNMAL1 was significantly correlated with better overall survival compared to those patients with negative expression. In contrast to this study though, Jiang et al. reported a decreased viability of the PanC cell lines following PNMAL1 silencing, thus indicating that PNMAL1 is an anti-apoptotic factor that promotes the survival of cancer cells [177]. The discrepancies observed may have resulted due to the employment of different methods of analysis (protein vs. gene expression) as well as the different types of samples used (tumour tissues vs. cell lines) in the respective studies. At the same time, these studies have also indicated that the mechanism of function of PNMAL1 in association with PDAC is not fully understood. In a different study though, this protein was reported to exert a pro-apoptotic function in neurons and its elevated expression was postulated to contribute towards neurodegenerative disorders [178].

Over the years, the overexpression of survivin in the context of PDAC has been widely studied [179,180,181,182]. Survivin is a member of apoptotic inhibitor protein that is reported to inhibit apoptosis in PDAC cells, hence, inversely correlated with the prognosis of PDAC as well as with higher rates of recurrence [183]. Using tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry, Zhou et al. had also studied the expression of survivin in the PDAC tumour and adjacently located non-tumour tissues obtained from the same patient [184]. Higher expression of survivin in the tumour tissues of patients further corroborates the previous reports for its strong association with poor prognosis of the disease via Kaplan–Meier survival analysis.

On the other hand, Bauden et al. conducted NPLC-MS/MS analysis on tumour tissues obtained from PDAC patients and normal pancreas head biopsy tissues from organ donors [185]. In this study, the team had identified histone variant H1.3 to be differently expressed and was further validated via immunohistochemistry analysis. The analysis demonstrated a decreased survival for patients with positive H1.3 expression, suggesting that this protein may serve as a prognostic biomarker for PDAC. In general, the alterations in the epigenetic processes which involve the modifications of histone variants are known to modify cell cycle progression, thus resulting in the development and progression of cancer (Ferraro, 2016). Since histone variant is also found to participate in the epigenetic regulation of PDAC which in turn contributes to the aggressiveness of the disease, hence, profiling of histone variants may prove as a useful method for identifying biomarkers of PDAC.

In another study, alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 (AGP1) was found upregulated in PDAC tissues compared to normal pancreatic tissue obtained from patients with benign pancreatic disease such as serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenoma and pancreatic pseudotumor via NPLC-MS/MS and later, verified by PRM [186]. Additional analysis using tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry (and, statistical analysis) also revealed that this protein significantly correlates with worse overall survival. Pathway analysis, on the other hand, demonstrated that this protein is prominently involved in the signalling cascade related to PDAC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion including MAPK, p53 and YY1 signalling thus indicating its potential as a prognostic biomarker for PDAC. At the same time, this study has considered the use of this protein as part of a biomarker panel for the early detection of PDAC as well [186]. The aberrant expression of AGP1 in PDAC has been discussed in other previous studies [187,188,189]. For example, Balmaña et al. utilised several analytical techniques (zwitterionic hydrophilic interaction capillary liquid chromatography electrospray ionisation-MS coupled with capillary zone electrophoresis and enzyme-linked lectin assay) to identify AGP1 glycoforms that are associated with PDAC [187]. In this study, α1-3 fucosylated glycoforms of AGP1 was observed elevated in the serum of PDAC patients compared to chronic pancreatitis patients and healthy controls. On the other hand, since this protein is associated with the signalling pathway in cancer cells, there is a high possibility for this protein to be upregulated in other cancers as well. Confirming this statement, Zhang et al. and Ayyub et al. reported an increase in the expression of this protein in laryngeal and lung cancers, respectively [190,191].

Quite different from the above studies, Kim et al. previously identified fibrinogen as a potential biomarker in the serum of PDAC patients as compared to healthy controls using MALDI-ToF/MS [192]. Five years later, they then validated this protein in PDAC patients, diabetic patients and healthy controls using ELISA and found that the serum fibrinogen levels were higher in PDAC patients compared to the healthy control group [193]. However, the analyses showed that the sensitivity and specificity of fibrinogen in discriminating PDAC and diabetic patients ranged between 67.4% and 83.6%, respectively, thus dismissing fibrinogen as a potential diagnostic biomarker for PDAC. Nevertheless, the same protein was found present at higher levels in patients with distant metastasis compared to those without when assessed for its prognostic values instead, thus indicating its correlation with poor prognosis of PDAC [193]. On the same note though, fibrinogen is an acute-phase protein that plays a common role in blood clotting and inflammatory response [194]. Hence, although its levels were indeed found to increase in advanced tumour stages, the specificity of this protein in PDAC remains to be determined due to the common role of this protein in other cancers [195,196,197,198] as well as other inflammatory conditions [199,200].

Biomarkers for Monitoring Treatment Response and Predicting Tumour Recurrence in PDAC

Although survival rates of patients with PDAC have improved to a certain extent (1-year survival rate of 18%) using gemcitabine [201], not all patients have benefited equally from this therapeutic regimen. This is due to the presence of extensive and dense stroma of PDAC attributing to the inability of the drug to penetrate, thus contributing to chemoresistance of gemcitabine [202]. Hence, biomarkers are needed for monitoring the response of patients post-treatment [203]. However, based on the review of recent research on PDAC, most biomarker studies that have been published using proteomics approaches were intended for diagnostic and prognostic applications. Conversely, biomarker studies focusing on monitoring treatment response among patients with PDAC appears to predominantly prefer genomic or transcriptomic approaches [26,204,205,206,207]. Hence, we report here only those studies that fell into the scope of this present review.

For example, Peng et al. compared the proteome profile of plasma obtained from PDAC patients who responded positively to chemotherapy and had longer survival (>12 months) with patients who responded poorly to treatment and had shorter survival (<12 months) to identify proteins that were differentially expressed between the two groups of patients via RPLC-MS/MS [208]. They discovered three proteins, including vitamin-K dependent protein Z (PZ), sex hormone-binding globulin and von Willebrand factor (VWF), which together with CA 19-9, provided better results in distinguishing patients that would benefit from chemotherapy. In this study, PZ, a protein that is involved in regulating blood coagulation [209] was observed to be highly abundant in positive treatment response patients. Although the mechanism of PZ in PDAC has still not been explored, a previous study on gastric cancer showed that decreased levels of PZ corresponded with advanced disease stage, suggesting that the varying levels of this protein may indicate a tumour stage [210]. However, like few other proteins discussed earlier in the present review, the validity of PZ as a biomarker for PDAC is still pre-mature since the biological significance of this protein has yet been elucidated.

Besides biomarkers for monitoring response of PDAC patients towards treatment, there are also studies that have been conducted to identify potential biomarkers for predicting recurrence of PDAC after the Whipple procedure for guiding and administering personalised treatment(s) in patients, if identified and validated.

Previously, Hu and group [211] identified galectin 4 as one of the proteins that are upregulated in the tissues of PDAC patients with longer survival (>45 months) through RPLC-MS/MS and later verified the data via PRM. Two years later, the same group of researchers conducted an immunohistochemical study to identify the significance of this particular protein in predicting the recurrence of PDAC among patients who had undergone surgical resection [212]. Here, they found galectin 4 to be significantly linked with disease recurrence within the first year of surgery and survival of patients after a year. Interestingly, another study by Kuhlmann et al. [213] similarly discovered galectin 4 as a biomarker candidate to monitor treatment response and tumour recurrence specifically for the exocrine-like subtype of PDAC. Under normal physiological conditions, galectin 4 plays various biological and functional roles including participating in apical trafficking, lipid raft stabilisation, aiding in the healing of intestinal wounds and promoting growth of axons in neurons [214]. In inflammatory and/or cancer conditions, on the other hand, this protein has been reported to exacerbate intestinal inflammation and promote tumour progression [214]. Further, galectin 4 additionally appears to have a conflicting pattern of expression in other cancers. For example, this protein was overexpressed in the serum and tissues of patients with cervical cancer [215] and lung adenocarcinoma [216]. While, at the same time, it was also found downregulated in expression in the tissues of patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma [217] and colorectal cancer [218]. Hence, further studies are needed to investigate whether galectin-4 should be implemented for use in clinical settings.

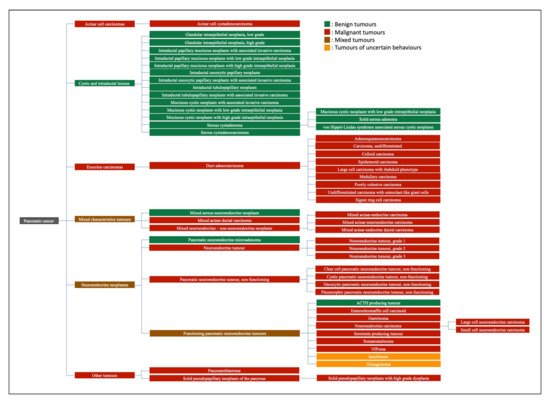

Of note, apart from the above-mentioned biomarker studies on PDAC, there is also other literature on the less common types of malignancies such as pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm [219], pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour [220] and insulinoma [221] using various proteomics approaches.

4. Challenges and Future Directions

Presently, from the perspective of diagnosis for PDAC, identifying an accurate and low-cost screening test for the early detection of PDAC remains a challenge but is of utmost importance. However, due to the low incidence of this disease, conducting screening tests on a population of a larger scale seems impossible. Another major challenge faced by healthcare professionals is the ability to distinguish early stage PDAC from other benign pancreatic conditions such as chronic pancreatitis [222]. In view of this, functional markers that could indicate the progression of PDAC such as stromal changes, microvascular density and tumour metabolism [223] in addition to studies that focus on other modifiable risk factors for PDAC such as diabetes mellitus [224] and obesity [225] are currently being studied. Furthermore, most treatment options that typically involve chemotherapy were found to have no improvement on patient life expectancy [226].

On the other hand, from the angle of study design, samples for biomarker research are usually obtained and validated in a case vs. control type of study and hence, the low prevalence of said disease in a particular population is often ignored. Taking the recent past research findings and its output into consideration, a longitudinal type of study would be deemed a better design/model for such undertakings. Secondly, the sample size in need of consideration. Most proteomics studies employ only a small sample size which in essence might not represent the actual prevalence or presentation of a particular disease in a population. A large cohort of samples is highly necessitated to establish ‘real’ biomarkers in a clinical setting. Thirdly, the choice of (biological) samples requires further refinement. For example, the heterogeneity of cancerous tissues is often not considered especially when tissue samples are used for the experiment [227]. This is because tissues are often homogenized prior to protein extraction for use for proteomic studies. On the other hand, cell lines may not accurately represent the primary cells of a particular cancer/tumour [228]. This is because cell lines are generally genetically manipulated and thus may have resulted in the alteration in their phenotype that might be distinct from the phenotype of the actual tumour [229].

Large amounts of money have been invested in the acquisition of proteomics technologies worldwide, with the hope of exploiting these advanced technologies for identifying highly specific and sensitive biomarkers with validated clinical outcomes. In spite of this, unfortunately, to date, only very few biomarkers have shown any significant clinical impact, if at all [230]. At the same time, implementation of such advanced (proteomic) techniques (e.g., MS) to measure the biomarkers (albeit validated) in a common clinical setting may not be practical and economical in terms of cost of equipment and (skilled) labour requirements.

Further, in most of the studies, the roles/mechanisms of the identified proteins in the pathogenesis of PDAC (e.g., why, and how the expression of proteins are correlated with the extent that they are secreted in normal or diseased conditions) remains unclear due to the singularity of techniques used thus limiting the interpretation of the significance of the study. This by no means only applies to proteomics but other fields of research as well (e.g., genomic [231,232], epigenomic—DNA methylation [233], single-cell transcriptomic [234] and metabolomics approaches [50,235]). One way to solve this is via the integration of multi-omics technologies that combine various approaches such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics, together with proteomics. Such a strategy is highly anticipated to translate the results of exploratory research into routine clinical practice, be it for either early detection and diagnosis, prognosis prediction or even to monitor treatment response and/or tumour recurrence.

Adjunct to the application of proteomics in biomarker investigations for PDAC, various other newer technologies are under development. For example, the nanoparticle-enabled blood test [236], incorporation of artificial intelligence into scientific discovery [237], scent test using Caenorhabditis elegans [238], in addition to the possible use of volatile organic compounds [239] for the management of patients with PDAC.

5. Conclusions

PDAC is the most prevalent disease of the pancreas, accounting for approximately 90% of all pancreatic malignancies. This disease has a poor prognosis due to the lack of early detection methods and is typically diagnosed at a late stage. Developing reliable, specific and sensitive biomarkers is of great importance to guide in the diagnosis of PDAC at an early stage and ascertain the prognosis of patients in order to serve as a guide in the timely and effective treatment of the disease [230]. The discovery of differently regulated yet unique protein signatures for various clinical utilities of PDAC via a proteomics approach provides deeper insights into cell functions, pathways and biological processes that are involved in the development and progression of the disease. The ever-evolving proteomics technologies have enabled researchers to grasp a basic understanding of the mechanisms of the disease, and for the identification of potential proteomics-based markers for PDAC, albeit with many challenges. Nevertheless, most of them only appear to demonstrate moderate sensitivity and/or specificity and are far from being considered for application in clinical settings. Hence, future biomarker investigation studies should essentially include several prerequisites such as the inclusion of an adequate number of clinically representative samples/populations, and improved yet appropriate study designs. Further, the incorporation of robust multi-omics (combination of genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics with proteomics) and/or other newer technologies is hoped upon to lead to the discovery of reliable diagnostic, prognostic, and biomarkers to monitor treatment responses that could be implemented into clinical practice in the near future.

References

- Artinyan, A.; Soriano, P.A.; Prendergast, C.; Low, T.; Ellenhorn, J.D.I.; Kim, J. The anatomic location of pancreatic cancer is a prognostic factor for survival. HPB 2008, 10, 371–376.

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Gaduputi, V. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: Global trends, etiology and risk factors. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 10–27.

- Khalaf, N.; El-Serag, H.B.; Abrams, H.R.; Thrift, A.P. Burden of pancreatic cancer: From epidemiology to practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 876–884.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Ilic, M.; Ilic, I. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 9694–9705.

- Parkin, D.M.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Pisani, P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 94, 153–156.

- Parkin, D.M.; Pisani, P.; Ferlay, J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of eighteen major cancers in 1985. Int. J. Cancer 1993, 54, 594–606.

- Ushio, J.; Kanno, A.; Ikeda, E.; Ando, K.; Nagai, H.; Miwata, T.; Kawasaki, Y.; Tada, Y.; Yokoyama, K.; Numao, N.; et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Epidemiology and risk factors. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 562.

- Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/458-malaysia-fact-sheets.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Merl, M.Y.; Li, J.; Saif, M.W. The first-line treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer. J. Pancreas 2010, 11, 148–150.

- Shaukat, A.; Kahi, C.J.; Burke, C.A.; Rabeneck, L.; Sauer, B.G.; Rex, D.K. ACG clinical guidelines: Colorectal cancer screening 2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 458–479.

- Wojtyla, C.; Bertuccio, P.; Wojtyla, A.; La Vecchia, C. European trends in breast cancer mortality, 1980–2017 and predictions to 2025. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 152, 4–17.

- Howlader, N.; Forjaz, G.; Mooradian, M.J.; Meza, R.; Kong, C.Y.; Cronin, K.A.; Mariotto, A.B.; Lowy, D.R.; Feuer, E.J. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 640–649.

- Michaud, D.S. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. Minerva Chir. 2004, 59, 99–111.

- Pereira, S.P.; Oldfield, L.; Ney, A.; Hart, P.A.; Keane, M.G.; Pandol, S.J.; Li, D.; Greenhalf, W.; Jeon, C.Y.; Koay, E.J.; et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 698–710.

- Kato, S.; Honda, K. Use of biomarkers and imaging for early detection of pancreatic cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 1965.

- Singhi, A.D.; Koay, E.J.; Chari, S.T.; Maitra, A. Early detection of pancreatic cancer: Opportunities and challenges. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 2024–2040.

- Zhou, B.; Xu, J.-W.; Cheng, Y.-G.; Gao, J.-Y.; Hu, S.-Y.; Wang, L.; Zhan, H.-X. Early detection of pancreatic cancer: Where are we now and where are we going? Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 231–241.

- Group, B.D.W. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: Preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95.

- Hasan, S.; Jacob, R.; Manne, U.; Paluri, R. Advances in pancreatic cancer biomarkers. Oncol. Rev. 2019, 13, 410.

- Wu, W.; Hu, W.; Kavanagh, J.J. Proteomics in cancer research. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2002, 12, 409–423.

- Maes, E.; Mertens, I.; Valkenborg, D.; Pauwels, P.; Rolfo, C.; Baggerman, G. Proteomics in cancer research: Are we ready for clinical practice? Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2015, 96, 437–448.

- Jelski, W.; Mroczko, B. Biochemical diagnostics of pancreatic cancer—Present and future. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 498, 47–51.

- Eissa, M.A.L.; Lerner, L.; Abdelfatah, E.; Shankar, N.; Canner, J.K.; Hasan, N.M.; Yaghoobi, V.; Huang, B.; Kerner, Z.; Takaesu, F.; et al. Promoter methylation of ADAMTS1 and BNC1 as potential biomarkers for early detection of pancreatic cancer in blood. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 59.

- Zhang, F.; Zhong, W.; Li, H.; Huang, K.; Yu, M.; Liu, Y. TP53 mutational status-based genomic signature for prognosis and predicting therapeutic response in pancreatic cancer. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 665265.

- Cheng, H.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Luo, G.; Lu, Y.; Jin, K.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.; et al. Analysis of ctDNA to predict prognosis and monitor treatment responses in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 2344–2350.

- Suenaga, M.; Fujii, T.; Yamada, S.; Hayashi, M.; Shinjo, K.; Takami, H.; Niwa, Y.; Sonohara, F.; Shimizu, D.; Kanda, M.; et al. Peritoneal lavage tumor DNA as a novel biomarker for predicting peritoneal recurrence in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 2277–2286.

- Kitagawa, T.; Taniuchi, K.; Tsuboi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Kohsaki, T.; Okabayashi, T.; Saibara, T. Circulating pancreatic cancer exosomal RNAs for detection of pancreatic cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 212–227.

- Du, Y.; Yao, K.; Feng, Q.; Mao, F.; Xin, Z.; Xu, P.; Yao, J. Discovery and validation of circulating EVL mRNA as a prognostic biomarker in pancreatic cancer. J. Oncol. 2021, 2021, 6656337.

- Jiao, Y.; Fu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. Aberrant FAM64A mRNA expression is an independent predictor of poor survival in pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211291.

- Tesfaye, A.A.; Azmi, A.S.; Philip, P.A. miRNA and gene expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 58–70.

- Vieira, N.F.; Serafini, L.N.; Novais, P.C.; Neto, F.S.L.; de Assis Cirino, M.L.; Kemp, R.; Ardengh, J.C.; Saggioro, F.P.; Gaspar, A.F.; Sankarankutty, A.K.; et al. The role of circulating miRNAs and CA19-9 in pancreatic cancer diagnosis. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 1638–1650.

- Daoud, A.Z.; Mulholland, E.J.; Cole, G.; McCarthy, H.O. MicroRNAs in pancreatic cancer: Biomarkers, prognostic, and therapeutic modulators. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1130.

- Xu, Y.-F.; Hannafon, B.N.; Zhao, Y.D.; Postier, R.G.; Ding, W.-Q. Plasma exosome miR-196a and miR-1246 are potential indicators of localized pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 77028–77040.

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, S.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, L.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, M.; Weng, J.; Li, B. miR-21 promotes EGF-induced pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by targeting Spry2. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1157.

- Capula, M.; Mantini, G.; Funel, N.; Giovannetti, E. New avenues in pancreatic cancer: Exploiting microRNAs as predictive biomarkers and new approaches to target aberrant metabolism. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 12, 1081–1090.

- Mikamori, M.; Yamada, D.; Eguchi, H.; Hasegawa, S.; Kishimoto, T.; Tomimaru, Y.; Asaoka, T.; Noda, T.; Wada, H.; Kawamoto, K.; et al. MicroRNA-155 controls exosome synthesis and promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42339.

- Takahasi, K.; Iinuma, H.; Wada, K.; Minezaki, S.; Kawamura, S.; Kainuma, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Shibuya, M.; Miura, F.; Sano, K. Usefulness of exosome-encapsulated microRNA-451a as a minimally invasive biomarker for prediction of recurrence and prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2018, 25, 155–161.

- Ma, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Pu, F.; Zhao, Q.; Peng, P.; Hui, B.; Ji, H.; Wang, K. Long non-coding RNA SNHG15 inhibits P15 and KLF2 expression to promote pancreatic cancer proliferation through EZH2-mediated H3K27me3. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84153–84167.

- Ramya Devi, K.T.; Karthik, D.; Mahendran, T.; Jaganathan, M.K.; Hemdev, S.P. Long noncoding RNAs: Role and contribution in pancreatic cancer. Transcription 2021, 12, 12–27.

- Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Lv, K.; Guan, J. Long non-coding RNA LINC00460 predicts poor survival and promotes cell viability in pancreatic cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 1369–1375.

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Kang, X.; Liu, S. The regulatory roles of long noncoding RNAs in the biological behavior of pancreatic cancer. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 145–151.

- Sefrioui, D.; Blanchard, F.; Toure, E.; Basile, P.; Beaussire, L.; Dolfus, C.; Perdrix, A.; Paresy, M.; Antonietti, M.; Iwanicki-Caron, I.; et al. Diagnostic value of CA19.9, circulating tumour DNA and circulating tumour cells in patients with solid pancreatic tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1017–1025.

- Wang, X.; Hu, L.; Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Xu, H.; Yu, H.; Song, Z.; Fei, J.; Zhong, Z. Clinical prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in the treatment of pancreatic cancer with gemcitabine chemotherapy. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1140.

- Wei, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Ma, T.; Li, G.; et al. Vimentin-positive circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for diagnosis and treatment monitoring in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019, 452, 237–243.

- Jiang, J.; Ye, S.; Xu, Y.; Chang, L.; Hu, X.; Ru, G.; Guo, Y.; Yi, X.; Yang, L.; Huang, D. Circulating tumor DNA as a potential marker to detect minimal residual disease and predict recurrence in pancreatic cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1220.

- Fahrmann, J.F.; Bantis, L.E.; Capello, M.; Scelo, G.; Dennison, J.B.; Patel, N.; Murage, E.; Vykoukal, J.; Kundnani, D.L.; Foretova, L.; et al. A plasma-derived protein-metabolite multiplexed panel for early-stage pancreatic cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 111, 372–379.

- Asai, Y.; Itoi, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Sofuni, A.; Tsuchiya, T.; Tanaka, R.; Tonozuka, R.; Honjo, M.; Mukai, S.; Fujita, M.; et al. Elevated polyamines in saliva of pancreatic cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 43.

- Battini, S.; Faitot, F.; Imperiale, A.; Cicek, A.E.; Heimburger, C.; Averous, G.; Bachellier, P.; Namer, I.J. Metabolomics approaches in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Tumor metabolism profiling predicts clinical outcome of patients. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 56.

- Phua, L.C.; Goh, S.; Tai, D.W.M.; Leow, W.Q.; Alkaff, S.M.F.; Chan, C.Y.; Kam, J.H.; Lim, T.K.H.; Chan, E.C.Y. Metabolomic prediction of treatment outcome in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients receiving gemcitabine. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 81, 277–289.

- Vreeker, G.C.M.; Hanna-Sawires, R.G.; Mohammed, Y.; Bladergroen, M.R.; Nicolardi, S.; Dotz, V.; Nouta, J.; Bonsing, B.A.; Mesker, W.E.; van der Burgt, Y.E.M.; et al. Serum N-glycome analysis reveals pancreatic cancer disease signatures. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 8519–8529.

- McDowell, C.T.; Klamer, Z.; Hall, J.; West, C.A.; Wisniewski, L.; Powers, T.W.; Angel, P.M.; Mehta, A.S.; Lewin, D.N.; Haab, B.B.; et al. Imaging mass spectrometry and lectin analysis of N-linked glycans in carbohydrate antigen-defined pancreatic cancer tissues. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021, 20, 100012.

- Doi, N.; Ino, Y.; Angata, K.; Shimada, K.; Narimatsu, H.; Hiraoka, N. Clinicopathological significance of core 3 O-glycan synthetic enzyme, β1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 6 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242851.

- Placencio-Hickok, V.; Lauzon, M.; Moshayedi, N.; Guan, M.; Kim, S.; Pandol, S.J.; Larson, B.K.; Gong, J.; Hendifar, A.E.; Osipov, A. Hyaluronan heterogeneity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, primary tumors, and sites of metastasis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. 15), e16231.

- Whatcott, C.J.; Diep, C.H.; Jiang, P.; Watanabe, A.; LoBello, J.; Sima, C.; Hostetter, G.; Shepard, H.M.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Han, H. Desmoplasia in primary tumors and metastatic lesions of pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3561–3568.

- Korc, M. Pancreatic cancer–associated stroma production. Am. J. Surg. 2007, 194 (Suppl. 4), S84–S86.

- Hruban, R.H.; Maitra, A.; Kern, S.E.; Goggins, M. Precursors to pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 36, 831–849.

- Yousaf, M.N.; Chaudhary, F.S.; Ehsan, A.; Suarez, A.L.; Muniraj, T.; Jamidar, P.; Aslanian, H.R.; Farrell, J.J. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and the management of pancreatic cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020, 7, e000408.

- Chen, G.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, M.; Zhang, T. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Pancreatology 2013, 13, 298–304.

- Zhang, L.; Sanagapalli, S.; Stoita, A. Challenges in diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2047–2060.

- Semelka, R.C.; Escobar, L.A.; Al Ansari, N.; Semelka, C.T.A. Magnetic resonance imaging of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. In Abdomen and Thoracic Imaging; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 209–231.

- González-Gómez, R.; Pazo-Cid, R.A.; Sarría, L.; Morcillo, M.Á.; Schuhmacher, A.J. Diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by immuno-positron emission tomography. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1151.

- Protiva, P.; Sahai, A.V.; Agarwal, B. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic neoplasms. Int. J. Gastrointest Cancer 2001, 30, 33–45.

- Kitano, M.; Minaga, K.; Hatamaru, K.; Ashida, R. Clinical dilemma of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for resectable pancreatic body and tail cancer. Dig. Endosc. 2022.

- Elbanna, K.Y.; Jang, H.-J.; Kim, T.K. Imaging diagnosis and staging of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A comprehensive review. Insights Imaging 2020, 11, 58.

- Stefanidis, D.; Grove, K.D.; Schwesinger, W.H.; Thomas, C.R., Jr. The current role of staging laparoscopy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: A review. Ann. Oncol. 2006, 17, 189–199.

- Shin, D.W.; Kim, J. The American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition staging system for the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Is it better than the 7th edition? Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2020, 9, 98–100.

- Amin, M.B. American Joint Committee on Cancer. In AJCC Cancer Staging Manual; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Haeberle, L.; Esposito, I. Pathology of pancreatic cancer. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 50.

- Song, J.-W.; Lee, J.-H. New morphological features for grading pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 175271.

- Khachfe, H.H.; Chahrour, M.A.; Habib, J.R.; Yu, J.; Jamali, F.R. A quality assessment of the information accessible to patients on the internet about the Whipple procedure. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 1853–1859.

- Klaiber, U.; Schnaidt, E.S.; Hinz, U.; Gaida, M.M.; Heger, U.; Hank, T.; Strobel, O.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Mihaljevic, A.L.; Büchler, M.W.; et al. Prognostic factors of survival after neoadjuvant treatment and resection for initially unresectable pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 154–162.

- Moletta, L.; Serafini, S.; Valmasoni, M.; Pierobon, E.S.; Ponzoni, A.; Sperti, C. Surgery for recurrent pancreatic cancer: Is it effective? Cancers 2019, 11, 991.

- Balaban, E.P.; Mangu, P.B.; Yee, N.S. Locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline summary. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017, 13, 265–269.

- Burris, H.A., 3rd; Moore, M.J.; Andersen, J.; Green, M.R.; Rothenberg, M.L.; Modiano, M.R.; Cripps, M.C.; Portenoy, R.K.; Storniolo, A.M.; Tarassoff, P.; et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: A randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 2403–2413.

- Cho, I.R.; Kang, H.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Chung, M.J.; Park, J.Y.; Park, S.W.; Song, S.Y.; An, C.; Park, M.-S.; et al. FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer: Single-center cohort study. World J. Gastrointest Oncol. 2020, 12, 182–194.

- Kanji, Z.S.; Edwards, A.M.; Mandelson, M.T.; Sahar, N.; Lin, B.S.; Badiozamani, K.; Song, G.; Alseidi, A.; Biehl, T.R.; Kozarek, R.A.; et al. Gemcitabine and taxane adjuvant therapy with chemoradiation in resected pancreatic cancer: A novel strategy for improved survival? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 1052–1060.

- Pereira, N.P.; Corrêa, J.R. Pancreatic cancer: Treatment approaches and trends. J. Cancer Metastatis Treat. 2018, 4, 30.

- Janssen, Q.P.; van Dam, J.L.; Bonsing, B.A.; Bos, H.; Bosscha, K.P.; Coene, P.P.L.O.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T.; Karsten, T.M.; van der Kolk, M.B.; et al. Total neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX versus neoadjuvant gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant gemcitabine for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (PREOPANC-2 trial): Study protocol for a nationwide multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 300.

- Amur, S.; LaVange, L.; Zineh, I.; Buckman-Garner, S.; Woodcock, J. Biomarker qualification: Toward a multiple stakeholder framework for biomarker development, regulatory acceptance, and utilization. Clin. Pharm. Therap. 2015, 98, 34–46.

- Lee, T.; Teng, T.Z.J.; Shelat, V.G. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9—Tumor marker: Past, present, and future. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 12, 468–490.

- Poruk, K.E.; Gay, D.Z.; Brown, K.; Mulvihill, J.D.; Boucher, K.M.; Scaife, C.L.; Firpo, M.A.; Mulvihill, S.J. The clinical utility of CA 19-9 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Diagnostic and prognostic updates. Curr. Mol. Med. 2013, 13, 340–351.

- Luo, G.; Jin, K.; Deng, S.; Cheng, H.; Fan, Z.; Gong, Y.; Qian, Y.; Huang, Q.; Ni, Q.; Liu, C.; et al. Roles of CA19-9 in pancreatic cancer: Biomarker, predictor and promoter. BBA—Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188409.

- Wu, E.; Zhou, S.; Bhat, K.; Ma, Q. CA 19-9 and pancreatic cancer. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 11, 53–55.

- Trifunovj, J.; Muzikravic, B.L.; Prvulovi, M.; Salma, S.; Nikolin, L.; Kukic, B. Evaluation of imaging techniques and CA 19-9 in differential diagnosis of carcinoma and other focal lesions of pancreas. Arch. Oncol. 2004, 12, 104–108.

- Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Alzahrani, M.; Wolff, R.A. The clinical utility of normal range carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level as a surrogate marker in evaluating response to treatment in pancreatic cancer—A report of two cases. J. Gastrointest Oncol. 2016, 7, E45–E51.

- Rieser, C.J.; Zenati, M.; Hamad, A.; Al Abbas, A.I.; Bahary, N.; Zureikat, A.H.; Zeh, H.J., 3rd; Hogg, M.E. CA19-9 on postoperative surveillance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Predicting recurrence and changing prognosis over time. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 3483–3491.

- Santucci, N.; Facy, O.; Ortega-Deballon, P.; Lequeu, J.-B.; Rat, P.; Rat, P. CA 19-9 predicts resectability of pancreatic cancer even in jaundiced patients. Pancreatology 2018, 18, 666–670.

- Kim, S.; Park, B.K.; Seo, J.H.; Choi, J.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, C.K.; Chung, J.B.; Park, Y.; Kim, D.W. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 elevation without evidence of malignant or pancreatobiliary diseases. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8820.

- Indellicato, R.; Zulueta, A.; Caretti, A.; Trinchera, M. Complementary use of carbohydrate antigens Lewis a, Lewis b, and sialyl-Lewis a (CA19-9 epitope) in gastrointestinal cancers: Biological rationale towards a personalized clinical application. Cancers 2020, 12, 1509.

- Sato, Y.; Fujimoto, D.; Uehara, K.; Shimizu, R.; Ito, J.; Kogo, M.; Teraoka, S.; Kato, R.; Nagata, K.; Nakagawa, A.; et al. The prognostic value of serum CA 19-9 for patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 890.

- Ansari, D.; Torén, W.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, D.; Andersson, R. Proteomic and genomic profiling of pancreatic cancer. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2019, 35, 333–343.

- Hall, C.; Clarke, L.; Pal, A.; Buchwald, P.; Eglinton, T.; Wakeman, C.; Frizelle, F. A review of the role of carcinoembryonic antigen in clinical practice. Ann. Coloproctol. 2019, 35, 294–305.

- Imaoka, H.; Mizuno, N.; Hara, K.; Hijioka, S.; Tajika, M.; Tanaka, T.; Ishihara, M.; Hirayama, Y.; Hieda, N.; Yoshida, T.; et al. Prognostic impact of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) on patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Pancreatology 2016, 16, 859–864.

- Meng, Q.; Shi, S.; Liang, C.; Liang, D.; Xu, W.; Ji, S.; Zhang, B.; Ni, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, X. Diagnostic and prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 4591–4598.

- Kato, H.; Kishiwada, M.; Hayasaki, A.; Chipaila, J.; Maeda, K.; Noguchi, D.; Gyoten, K.; Fujii, T.; Iizawa, Y.; Tanemura, A.; et al. Role of serum carcinoma embryonic antigen (CEA) level in localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma: CEA level before operation is a significant prognostic indicator in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgical resection: A retrospective analysis. Ann. Surg. 2020.

- Kim, H.; Kang, K.N.; Shin, Y.S.; Byun, Y.; Han, Y.; Kwon, W.; Kim, C.W.; Jang, J.-Y. Biomarker panel for the diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 1443.

- Chen, E.I.; Yates, J.R. Cancer proteomics by quantitative shotgun proteomics. Mol. Oncol. 2007, 1, 144–159.

- Aslam, B.; Basit, M.; Nisar, M.A.; Khurshid, M.; Rasool, M.H. Proteomics: Technologies and their applications. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2017, 55, 182–196.

- Hardt, M. Advances in mass spectrometry-based proteomics and its application in cancer research. In Unravelling Cancer Signaling Pathways: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Bose, K., Chaudhari, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 89–112.

- Zhang, F.; Deng, C.K.; Wang, M.; Deng, B.; Barber, R.; Huang, G. Identification of novel alternative splicing biomarkers for breast cancer with LC-MS/MS and RNA-Seq. BMC Bioinform. 2020, 21, 541.

- Guo, A.J.; Wang, F.J.; Ji, Q.; Geng, H.W.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.Q.; Tie, W.W.; Liu, X.Y.; Thorne, R.F.; Liu, G. Proteome analyses reveal S100A11, S100P, and RBM25 are tumor biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2021, 15, 2000056.

- Terkelsen, T.; Pernemalm, M.; Gromov, P.; Børresen-Dale, A.-L.; Krogh, A.; Haakensen, V.D.; Lethiö, J.; Papaleo, E.; Gromova, I. High-throughput proteomics of breast cancer interstitial fluid: Identification of tumor subtype-specific serologically relevant biomarkers. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 429–461.

- Luu, G.T.; Sanchez, L.M. Toward improvement of screening through mass spectrometry-based proteomics: Ovarian cancer as a case study. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 469, 116679.

- Nusinow, D.P.; Szpyt, J.; Ghandi, M.; Rose, C.M.; McDonald, E.R.; Kalocsay, M.; Jané-Valbuena, J.; Gelfand, E.; Schweppe, D.K.; Jedrychowski, M.; et al. Quantitative proteomics of the cancer cell line encyclopedia. Cell 2020, 180, 387–402.e16.

- Lindemann, C.; Thomanek, N.; Hundt, F.; Lerari, T.; Meyer, H.E.; Wolters, D.; Marcus, K. Strategies in relative and absolute quantitative mass spectrometry based proteomics. Biol. Chem. 2017, 398, 687–699.

- Song, E.; Gao, Y.; Wu, C.; Shi, T.; Nie, S.; Fillmore, T.L.; Schepmoes, A.A.; Gritsenko, M.A.; Qian, W.-J.; Smith, R.D.; et al. Targeted proteomic assays for quantitation of proteins identified by proteogenomic analysis of ovarian cancer. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170091.

- Jimenez-Luna, C.; Torres, C.; Ortiz, R.; Dieguez, C.; Martinez-Galan, J.; Melguizo, C.; Prados, J.C.; Caba, O. Proteomic biomarkers in body fluids associated with pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16573–16587.

- Agrawal, S. Potential prognostic biomarkers in pancreatic juice of resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 8, 255–260.

- Song, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Jin, X.; Jing, R.; Yang, J.-H.; et al. Label-free quantitative proteomics unravels carboxypeptidases as the novel biomarker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 691–699.

- Park, J.; Han, D.; Do, M.; Woo, J.; Wang, J.I.; Han, Y.; Kwon, W.; Kim, S.-W.; Jang, J.-Y.; Kim, Y. Proteome characterization of human pancreatic cyst fluid from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 31, 1761–1772.

- Saraswat, M.; Joenväärä, S.; Seppänen, H.; Mustonen, H.; Haglund, C.; Renkonen, R. Comparative proteomic profiling of the serum differentiates pancreatic cancer from chronic pancreatitis. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 1738–1751.

- Debernardi, S.; O’Brien, H.; Algahmdi, A.S.; Malats, N.; Stewart, G.D.; Plješa-Ercegovac, M.; Costello, E.; Greenhalf, W.; Saad, A.; Roberts, R.; et al. A combination of urinary biomarker panel and PancRISK score for earlier detection of pancreatic cancer: A case-control study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003489.

- Deer, E.L.; González-Hernández, J.; Coursen, J.D.; Shea, J.E.; Ngatia, J.; Scaife, C.L.; Firpo, M.A.; Mulvihill, S.J. Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas 2010, 39, 425–435.

- Takagi, K.; Imura, J.; Shimomura, A.; Noguchi, A.; Minamisaka, T.; Tanaka, S.; Nishida, T.; Hatta, H.; Nakajima, T. Establishment of highly invasive pancreatic cancer cell lines and the expression of IL-32. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 2888–2896.

- Collisson, E.A.; Sadanandam, A.; Olson, P.; Gibb, W.J.; Truitt, M.; Gu, S.; Cooc, J.; Weinkle, J.; Kim, G.E.; Jakkula, L.; et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 500–503.

- Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Go, V.L.; Hu, S. Membrane proteomic analysis of pancreatic cancer cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010, 17, 74.

- Bulle, A.; Lim, K.-H. Beyond just a tight fortress: Contribution of stroma to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 249.

- Zheng, J.; Hernandez, J.M.; Doussot, A.; Bojmar, L.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Costa-Silva, B.; van Beek, E.J.A.H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Askan, G.; et al. Extracellular matrix proteins and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules characterize pancreatic duct fluid exosomes in patients with pancreatic cancer. HPB 2018, 20, 597–604.

- Han, C.; Liu, T.; Yin, R. Biomarkers for cancer-associated fibroblasts. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 64.

- Kruger, D.; Yako, Y.Y.; Devar, J.; Lahoud, N.; Smith, M. Inflammatory cytokines and combined biomarker panels in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Enhancing diagnostic accuracy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221169.

- McGuigan, A.J.; Coleman, H.G.; McCain, R.S.; Kelly, P.J.; Johnston, D.I.; Taylor, M.A.; Turkington, R.C. Immune cell infiltrates as prognostic biomarkers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2021, 7, 99–112.

- Bressy, C.; Lac, S.; Nigri, J.; Leca, J.; Roques, J.; Lavaut, M.-N.; Secq, V.; Guillaumond, F.; Bui, T.-T.; Pietrasz, D.; et al. LIF drives neural remodeling in pancreatic cancer and offers a new candidate biomarker. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 909–921.

- Suzuki, Y.; Takadate, T.; Mizuma, M.; Shima, H.; Suzuki, T.; Tachibana, T.; Shimura, M.; Hata, T.; Iseki, M.; Kawaguchi, K.; et al. Stromal expression of hemopexin is associated with lymph-node metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235904.

- Tao, J.; Yang, G.; Zhou, W.; Qiu, J.; Chen, G.; Luo, W.; Zhao, F.; You, L.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, T.; et al. Targeting hypoxic tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 14.

- Yang, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Chen, L.; Ma, L.; Larcher, L.M.; Chen, S.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Progress, opportunity, and perspective on exosome isolation—Efforts for efficient exosome-based theranostics. Theranostics 2020, 10, 3684–3707.

- Li, W.; Li, C.; Zhou, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, D. Role of exosomal proteins in cancer diagnosis. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 145.

- Melo, S.A.; Luecke, L.B.; Kahlert, C.; Fernandez, A.F.; Gammon, S.T.; Kaye, J.; LeBleu, V.S.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Weitz, J.; Rahbari, N.; et al. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 523, 177–182.

- Vajaria, B.N.; Patel, P.S. Glycosylation: A hallmark of cancer? Glycoconj. J. 2017, 34, 147–156.

- Munkley, J. The glycosylation landscape of pancreatic cancer (review). Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 2569–2575.

- Pan, S.; Brentnall, T.A.; Chen, R. Glycoproteins and glycoproteomics in pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 9288.

- Kailemia, M.J.; Park, D.; Lebrilla, C.B. Glycans and glycoproteins as specific biomarkers for cancer. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 395–410.

- Wang, S.; You, L.; Dai, M.; Zhao, Y. Quantitative assessment of the diagnostic role of mucin family members in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 192.

- Wang, S.; You, L.; Dai, M.; Zhao, Y. Mucins in pancreatic cancer: A well-established but promising family for diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 10279–10289.

- Hughes, C.S.; Moggridge, S.; Müller, T.; Sorensen, P.H.; Morin, G.B.; Krijgsveld, J. Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation for proteomics experiments. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 68–85.

- Greco, V.; Piras, C.; Pieroni, L.; Urbani, A. Direct assessment of plasma/serum sample quality for proteomics biomarker investigation. In Serum/Plasma Proteomics; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–21.

- Cai, T.; Yang, F. Strategies for characterization of low-abundant intact or truncated low-molecular-weight proteins from human plasma. Enzymes 2017, 42, 105–123.

- Keshishian, H.; Burgess, M.W.; Specht, H.; Wallace, L.; Clauser, K.R.; Gillette, M.A.; Carr, S.A. Quantitative, multiplexed workflow for deep analysis of human blood plasma and biomarker discovery by mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1683–1701.

- Hashim, O.H.; Jayapalan, J.J.; Lee, C.-S. Lectins: An effective tool for screening of potential cancer biomarkers. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3784.

- Ignjatovic, V.; Geyer, P.E.; Palaniappan, K.K.; Chaaban, J.E.; Omenn, G.S.; Baker, M.S.; Deutsch, E.W.; Schwenk, J.M. Mass spectrometry-based plasma proteomics: Considerations from sample collection to achieving translational data. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 4085–4097.

- Kaboord, B.; Smith, S.; Patel, B.; Meier, S. Enrichment of low-abundant protein targets by immunoprecipitation upstream of mass spectrometry. In Proteomic Profiling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 135–151.

- Kumar, S.; Mohan, A.; Guleria, R. Biomarkers in cancer screening, research and detection: Present and future: A review. Biomarkers 2006, 11, 385–405.

- Goossens, N.; Nakagawa, S.; Sun, X.; Hoshida, Y. Cancer biomarker discovery and validation. Transl. Cancer Res. 2015, 4, 256–269.

- Guo, X.; Lv, X.; Fang, C.; Lv, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, D.; Zhao, J.; Ma, Y.; Xue, Y.; Bai, Q.; et al. Dysbindin as a novel biomarker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma identified by proteomic profiling. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 1821–1829.

- Fang, C.; Guo, X.; Lv, X.; Yin, R.; Lv, X.; Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Bai, Q.; Yao, X.; Chen, Y. Dysbindin promotes progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via direct activation of PI3K. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 9, 504–515.

- Zhu, D.; Zheng, S.; Fang, C.; Guo, X.; Han, D.; Tang, M.; Fu, H.; Jiang, M.; Xie, N.; Nie, Y.; et al. Dysbindin promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma metastasis by activating NF-κB/MDM2 via miR-342–3p. Cancer Lett. 2020, 477, 107–121.

- Sogawa, K.; Takano, S.; Iida, F.; Satoh, M.; Tsuchida, S.; Kawashima, Y.; Yoshitomi, H.; Sanda, A.; Kodera, Y.; Takizawa, H.; et al. Identification of a novel serum biomarker for pancreatic cancer, C4b-binding protein α-chain (C4BPA) by quantitative proteomic analysis using tandem mass tags. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 949–956.

- Mikami, M.; Tanabe, K.; Matsuo, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Miyazawa, M.; Hayashi, M.; Asai, S.; Ikeda, M.; Shida, M.; Hirasawa, T.; et al. Fully-sialylated alpha-chain of complement 4-binding protein: Diagnostic utility for ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 520–528.

- Suman, S.; Basak, T.; Gupta, P.; Mishra, S.; Kumar, V.; Sengupta, S.; Shukla, Y. Quantitative proteomics revealed novel proteins associated with molecular subtypes of breast cancer. J. Proteom. 2016, 148, 183–193.

- Sogawa, K.; Yamanaka, S.; Takano, S.; Sasaki, K.; Miyahara, Y.; Furukawa, K.; Takayashiki, T.; Kuboki, S.; Takizawa, H.; Nomura, F.; et al. Fucosylated C4b-binding protein α-chain, a novel serum biomarker that predicts lymph node metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 127.

- Tran Cao, H.S.; Zhang, Q.; Sada, Y.H.; Silberfein, E.J.; Hsu, C.; Van Buren, G., II; Chai, C.; Katz, M.H.G.; Fisher, W.E.; Massarweh, N.N. Value of lymph node positivity in treatment planning for early stage pancreatic cancer. Surgery 2017, 162, 557–567.

- Kim, J.; Hoffman, J.P.; Alpaugh, R.K.; Rhim, A.D.; Reichert, M.; Stanger, B.Z.; Furth, E.E.; Sepulveda, A.R.; Yuan, C.-X.; Won, K.-J.; et al. An iPSC line from human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoes early to invasive stages of pancreatic cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 2088–2099.

- Kim, J.; Bamlet, W.R.; Oberg, A.L.; Chaffee, K.G.; Donahue, G.; Cao, X.-J.; Chari, S.; Garcia, B.A.; Petersen, G.M.; Zaret, K.S. Detection of early pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with thrombospondin-2 and CA19-9 blood markers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, 5583.

- Le Large, T.Y.S.; Meijer, L.L.; Paleckyte, R.; Boyd, L.N.C.; Kok, B.; Wurdinger, T.; Schelfhorst, T.; Piersma, S.R.; Pham, T.V.; van Grieken, N.C.T.; et al. Combined expression of plasma thrombospondin-2 and CA19-9 for diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and distal cholangiocarcinoma: A proteome approach. Oncologist 2020, 25, e634–e643.

- Ethun, C.G.; Lopez-Aguiar, A.G.; Pawlik, T.M.; Poultsides, G.; Idrees, K.; Fields, R.C.; Weber, S.M.; Cho, C.; Martin, R.C.; Scoggins, C.R.; et al. Distal cholangiocarcinoma and pancreas adenocarcinoma: Are they really the same disease? A 13-institution study from the US extrahepatic biliary malignancy consortium and the central pancreas consortium. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2017, 224, 406–413.

- Nakamura, T.; Furukawa, Y.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsunoda, T.; Ohigashi, H.; Murata, K.; Ishikawa, O.; Ohgaki, K.; Kashimura, N.; Miyamoto, M.; et al. Genome-wide cDNA microarray analysis of gene expression profiles in pancreatic cancers using populations of tumor cells and normal ductal epithelial cells selected for purity by laser microdissection. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2385–2400.

- Yoneyama, T.; Ohtsuki, S.; Honda, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Iwasaki, M.; Uchida, Y.; Okusaka, T.; Nakamori, S.; Shimahara, M.; Ueno, T.; et al. Identification of IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 as compensatory biomarkers for CA19-9 in early-stage pancreatic cancer using a combination of antibody-based and LC-MS/MS-based proteomics. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161009.

- Baxter, R.C. IGF binding proteins in cancer: Mechanistic and clinical insights. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 329–341.

- Gao, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Chua, C.Y.; Phillips, L.M.; Ren, H.; Fleming, J.B.; Wang, H.; et al. IGFBP2 activates the NF-κB pathway to drive epithelial–mesenchymal transition and invasive character in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 6543–6554.