Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Nora Tang and Version 4 by Nora Tang.

To develop the hotel industry’s competitiveness, research on satisfaction and revisit intentions has always been important. More research has recently focused on guests’ pro-environmental behaviors and low-carbon management in the hotel industry. The suitability of a leisure environment could positively impact guest satisfaction, which positively affected their willingness to revisit.

- recreationist-environment fit

- guests’ satisfaction

- revisit intention

- guests' pro-environmental behavior

1. Green Luxury Hotel

Being a low-carbon producer is a new approach to sustainable economic development [1], and low-carbon has become a new focus in green hospitality management research [2][3]. Hotel carbon emissions, representing large contributions to climate change, have attracted significant attention from society. Therefore, low-carbon research for hotels has become a new focus in hospitality management [4].

The concepts of ‘green’ and ‘low carbon’ are different. ‘Green’ hospitality management focuses on hotels’ environmental protection and green resource human management [5]. As part of the green ideology, ‘low carbon’ focuses on carbon emission reductions [6]. Since the beginning of low-carbon transformation, green hotels have implemented low-carbon behaviors, such as low-carbon technology, low-carbon talent, low-carbon culture, and green marketing [7][8][9]. Fraj et al. [10] concluded that proactive environmental strategies and environmental innovations would assist in developing greener hotel operations and management. As global warming is recognized as one of the most significant global risks, hospitality management must focus on sustainable low-carbon behaviors [11][12].

Luxury hotels have a high potential to engage in high energy consumption and carbon emissions. Yi [13] studied the carbon emission of hotels from the perspective of carbon footprints. He pointed out that the higher the level of the hotels, the greater the carbon footprint. Zhang [14] found that a medium-sized four-star hotel emits at least 4200 tons of carbon dioxide every year. As a result, luxury hotels should be primarily responsible for implementing low-carbon activities [11]; thus, many luxury hotel chains have implemented low-carbon measures in many countries. For example, Malaysia achieved a 33% carbon emission intensity to GDP reduction in 2019, relative to 2005 levels, and is well on its way to its target of cutting 45% of emissions by 2030. Overall, however, significant efforts are still needed to reduce the country’s carbon footprint and mitigate global warming. Therefore, leading luxury hotels in Malaysia have begun implementing carbon emissions reduction measures. For instance, in a new partnership with Proof & Company, Four Seasons Malaysia implemented an ecoSPIRITS system at Bar Trigona at the Four Seasons Hotel, Kuala Lumpur and the Rhu Bar at Four Seasons Resort, Langkawi [15]. EcoSPIRITS is an innovative technology that significantly reduces packaging waste across the premium spirits supply chain. By drastically reducing the packaging and transport costs, ecoSPIRITS eliminates up to 80% of the spirit consumption carbon footprint. In 2020, 40 billion glass spirit bottles were produced, generating 22 million tons of carbon emissions; therefore, one bottle emits 550 g as carbon emissions, meaning that each cocktail or spirit poured through the ecoSPIRITS system can reduce emissions by 30 g.

In China, the development of low-carbon hotels is still in the initial stage. Since China’s promised goal of 3060, many luxury hotels under green ranking have strengthened low-carbon management. For example, the Shangri-La hotel in Sanya promoted green design, and its green building received a silver award from LEED Green Building in the United States [16]. For another example, the Hainan Guest Hotel promoted low-carbon facilities and recyclable decorations to promote its low-carbon transformation. Moreover, it started green marketing in 2017 and realized four million RMB sales income [17]. This indicates that the low-carbon behavior of green luxury hotels can achieve both environmental and business performance.

As mentioned, the National Green Hotel Working Committee of China and the China Hotel Association proposed the first batch of 100 model hotels with “green restaurants, rest assured consumption”. This study chose seven luxury hotels from these 100 model hotels to examine if the low-carbon service of green luxury hotels can promote business performance and green image.

2. Recreationist-Environment Fit

People interact with the tourist environment [18]. Specifically, individuals affect and are affected by environments through tourism [19][20]. Therefore, there is an interactive relationship between tourists and the environment [21]. The effect of these two ideas is a relationship that scholars refer to as R-E Fit theory [22][23].

Scholars first started to study the Person-Environment fit (P-E fit) theory in living and work environments before R-E Fit [24][25]. Kristof [26] introduced person-organization fit as “the compatibility between people and organizations that occurs when: (a) at least one entity provides what the other needs or (b) they share similar fundamental characteristics, or (c) both.” The study introduced supplementary fit and complementary fit. Supplementary fit emphasizes the consistency between people and the environment. i.e., individuals and other members of the work environment have similar characteristics, and members attract and trust each other, leading to better communication [27]. Complementary fit is the degree of adaptation between individuals and living/work environments, emphasizing the degree of complementarity between them, which is essentially the fit between members and environments [28]. Later, Edwards [29] proposed a needs-supplies fit, which meant that the environment’s value could meet individual needs, and the requirements-abilities fit, which advocates that people’s skills, knowledge, and other resources could meet the requirements of the environment. P-E fit theory has been widely used in the fields of resource management and organizational behavior, such as person-job fit, person-group fit, and person-organization fit [30][31][32]. Later, Tsaur et al. [33] attempted to use P-E fit theory on the tourism environment; he also proposed R-E Fit and developed the correspondent R-E Fit Scale (REFS). Six dimensions were identified in this scale: natural resources, recreation functions, interpersonal opportunists, facilities, activity knowledge/skills, and operation/management. Since then, R-E Fit theory has been widely related to tourists’ experiences and destination environments [23][34].

Scholars want to use R-E Fit theory in tourism to analyze the relationship between tourists’ behaviors and destination environments [35]. According to past studies, there are three types of R-E Fit: needs-supplies, requirements-abilities, and complementary fit [36]. Needs-supplies fit means that the needs of tourists match the environment’s supplies, such as natural resources, environmental facilities, environmental functions, and interpersonal opportunities; if their needs are met, then the tourists would be more willing to participate in low-carbon activities and may have high satisfaction [37]. When the tourists’ knowledge and abilities meet the environment’s requirements, it can also increase revisit intention [38], a process referred to as the requirements-abilities fit. Complementary fit refers to the relationship between tourists and the environment or the environmental managers [39]. In other words, tourists and managers have similar values regarding the maintenance facilities and management [40][41].

Hospitality is an integral part of tourism. As mentioned, the goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality prompted the tourism and hotel sectors to begin low-carbon transformation. Under this circumstance, hotels, especially luxury hotels, have started low-carbon hospitality management [42][7][5]. In the early stages, hotels developed low-carbon management through energy saving and renewable energy. For example, Dalton et al. [43] proposed that hotels make reasonable use of conventional energy, adopt energy-saving technology, and improve energy efficiency. They investigated guests’ attitudes toward using renewable energy in Australian tourist resort hotels, and more than 50% of guests held positive attitudes toward pleasant accommodation environments and renewable energy. In the middle stage, hotels improved their facilities and innovated green buildings to realize low-carbon operations. For instance, Hoshinoya hotel in Japan installed a semi-closed window on the roof to become a “wind house” without an air conditioner [44]. Furthermore, the “ceiling” installed at the GAIA hotel in the United States can fully use solar energy and reduce carbon emissions by two thirds. This hotel is the most eco-friendly hotel globally [45]. In the later stage, low-carbon management was combined with green training, low-carbon investment, and green marketing. Employees acted as “windows” of low carbon to promote the hotel’s low-carbon culture. Cop et al. [7] mentioned that luxury hotels needed to strengthen employees’ low-carbon training to satisfy guests’ low-carbon needs. Moreover, Dogru et al. [46] found that the shareholders’ low-carbon investment could improve low-carbon technology and the development of low-carbon talent, and Chung [47] found that many luxury hotels carried out green marketing. The study mentioned that hotels knew that growing environmental issues could change consumers’ buying preferences. In that case, hotels must provide low-carbon products to attract guests to make green consumption choices. To illustrate, Sheraton provides green rooms, W Hotel recycled Coca-Cola bottle caps to make bedsheets to promote the green movement, and Vienna Hotel provides cotton and linen bedding for sale to guests.

The low-carbon behavior of hotels can bring about carbon efficiency and fit consumers’ needs. In recent years, more hotels have adopted eco-friendly practices and implemented innovative technologies to reduce their carbon footprint and create a viable green image [48][49]. Guests have paid attention to the importance of changing lifestyles and engaging in eco-friendly behaviors [50]. Many hotel guests value hotels that offer up-to-date technology and demonstrate sustainability efforts through various sustainable programs [51]. Additionally, guests are more willing to join in the low-carbon activities and spread positive experiences via word of mouth [52][53]. In that case, low-carbon lodging experiences can fit their eco-friendly needs [54]. Overall, hotels’ low-carbon practices are in accordance with the R-E Fit; however, most R-E Fit studies in tourism management relate to place attachment [22][55], and there are few in hospitality management. Thus, this study examines the R-E Fit in the hospitality sector. Furthermore, according to Tsaur et al. [22][33], regarding the six dimensions of R-E Fit, this study presents facilities, environmental resources, environmental functions, interpersonal opportunities, activity knowledge/skills, and management as the R-E Fit of the hotel industry.

3. Guests’ Satisfaction

Various studies have found that improved guest satisfaction ultimately leads to greater customer loyalty and word-of-mouth recommendations [56][57]. Increasing competition in product marketing has forced companies to implement different strategies to attract and retain guests [58]. Among the different strategies that companies have used is the personalization of products to meet customer needs [59]. Guests’ satisfaction is “a person’s feelings of pleasure or disappointment that results from comparing a product’s perceived performance or outcome with his/her expectations” [60]. A study by Lee et al. [61] indicated that hospitals could improve customer satisfaction and loyalty through efficient operations, employee engagement, and service quality. They also found that this high-performance work system in healthcare organizations stimulated employee reaction and service quality. Therefore, a customer may continue to increase the scope and frequency of their relationship with the service provider or recommend the service provider to other potential customers. Lee [62] suggests that guest satisfaction is linked to loyalty, which, in turn, is linked to the performance of service organizations. In short, a satisfied guest is more likely to return, and a returning customer is more likely to purchase additional items. A customer purchasing additional items with which they are satisfied is more likely to develop brand-loyalty [63][64][65].

In the hospitality industry, luxury hotels characterize excellent service, symbolizing the wealth and status of its patrons. Recently, many luxury hotels aiming to enhance market competitiveness have been exploring their characteristics, such as green building design, landscape design, and service quality [66]. The development of low carbon provides a new marketing perspective for green hotels. Many studies have proven that low-carbon promotion could improve both direct financial performance (income, operational cost saving, new business) and non-financial performance (guests’ satisfaction and loyalty, turnover rate, green image) [67][68][69].

Specifically, Williams [70] mentioned four key components for green hotels: eco-service, eco-accommodation, eco-cuisine, and eco-programming. Aksu et al. [71] explored the components of eco-service quality at hotels and found that the critical determinants for sensitive customers’ satisfaction were equipment, staff and food, and practice. Hou and Wu [66] investigated tourists’ perceptions of green building design and their intention of staying in a green hotel and found two primary contributors. Firstly, (a) green building design could save operational cost, and high environmental concern from tourists could influence the perceived importance of green building design and their intention of staying in hotels, and secondly, (b) the relationship between tourists’ environmental concerns and intention of staying could help the development of green marketing activities. Yusof et al. [72] also confirmed that green and non-green status hoteliers should develop green practices because they significantly affect guests’ satisfaction.

With the development of eco-cites in China, hotels started considering the topic of eco-hotels. In addition to traditional low-carbon behaviors, such as refusing disposable items and reusing towels, hotels can pay more attention to advanced behaviors to promote low-carbon services and tourist participation [73][74]. For example, such hotels set up low-carbon publicity walls, present environmentally friendly gifts, provide organic food, and carry out low-carbon activities [75]. These measures can share the hotels’ low-carbon concepts and stimulate the guests’ low-carbon resonance [52][76][77]. This could enable a hotel to promote unique characteristics and attract more guests [78][79].

4. Revisit Intention

The existing service sector literature has extensively studied the relationship between satisfaction and guests’ intentions to revisit in the past few decades. Fornell [80] suggested that the more the customers were satisfied with the services, the greater their willingness to revisit. At the tourism level, various studies have recognized the importance of satisfaction in predicting tourists’ intention to revisit and attempted to investigate the relationship in the context of destination, for example, Mannan et al. [81] argued that customer satisfaction positively influenced revisit intention, and trust mediated the satisfaction–revisit intention relation in restaurants. Seetanah et al. [82] had the same conclusion of satisfaction and revisit intention in airport services. According to past empirical destination research, tourists choose destinations with attributes that they believe can meet their needs [83].

In the context of tourism, service quality, satisfaction, involvement, previous experience, place attachment, and perceived value can influence guests’ intentions to revisit [84][85][86]. Of these, satisfaction is one of the most important determinants, which is widely understood in tourism experiences [81][87]. Several studies have proven that the more the guests express their satisfaction with destinations, the more likely they will be to revisit [88][89]. Tourists’ intention to revisit refers to the possibility they plan to return to the same destination, which is a specific factor of good post-consumer behavior and a key component of tourist loyalty [90].

A satisfied hotel guest is not equal to a loyal guest due to the special characteristics of the hotel industry [91]; in other words, unless they have an irreplaceable positive impression of this destination, a guest could feel satisfied with the hotel’s services, but not necessarily revisit the same hotel. In that case, it is easy to satisfy a customer but difficult, in the hospitality industry, to obtain a loyal customer [92]. Low-carbon operation is a potential selling point for the hotel sector and has become a new character factor among green hotels [93]. Low-carbon service in hotels has helped the development of the green image [94]. The general feelings of resource use, environmental functions, and facilities help build overall impressions, becoming different dynamic and irreplaceable green images among guests [95]. An irreplaceable green image means meeting more consumers’ needs, which leads to more satisfaction and a stronger willingness to revisit [9][91].

5. Guests’ Pro-Environmental Behavior

Pro-environmental behavior (PEB) refers to an individual’s daily behavior that positively affects the environment and is directly related to the environment [96]. There is a variety of PEB which Moeller et al. [97] called the environmental responsibility behavior of ecotourists. Levinson [98] and Wynes and Nicholas [99] explained that PEB changed consumption patterns to relatively low-impact alternatives in individuals’ consumption dimensions. In the tourism and hotel dimension, guests’ pro-environmental behaviors (GPEB) are defined as changing their behaviors to do the least harm to the environment [100][101]. For example, Orsato [102] explained that GPEB was choosing eco-friendly transportation, rejecting the disposing of goods, or joining in low-carbon and green travels. Furthermore, Namkung and Jang [103] presented three dimensions of GPEB: guests’ willingness to protect the destination environment, awareness of reducing pollution, and intention to participate in low-carbon consumption. In this study, GEPB refers to eco-friendly and green consumption behaviors in hotels and guests’ daily lives.

GPEB is a basis for strategic management decisions, particularly in hotels [10]. On the one hand, GPEB is a low-carbon consumption behavior [104][37] where guests appreciate the low-carbon service [105]. Moreover, they are willing to buy low-carbon products and participate in low-carbon activities [106]. On the other hand, Han and Hyun [107] pointed out that GPEB is a low-carbon requirement for hotel service. Dani et al. [108], Han and Hwang [109], and Almomani et al. [9] showed that if a hotel improved its low-carbon service, it could increase tourist satisfaction and loyalty.

That means that as a form of low-carbon behavior commercialization, hotels’ low-carbon services impact GPEB. The design of low-carbon services also considers the requirements of GPEB [66][110]. The successful low-carbon management solves the carbon emission issue and satisfies the guest for the service rendered or understanding of the hotel culture [111]. In that case, low-carbon hotels can make long-term profitability. Accordingly, the manager needs to focus on GPEB [112][48]; hotels must know about guests’ GPEB demands so that they can provide suitable service and achieve tourist satisfaction and loyalty [113][53][114]. Thus, the study of GPEB needs to be associated with low-carbon service and business performance. Its primary purpose is to help hotels improve their service quality and then realize business performance (customer satisfaction and revisit intention) [78][115].

Trang et al. [100] and Yadav et al. [116] showed that GPEB had connections with guests’ satisfaction and revisit intention in the hospitality sector. Additionally, Scheibehenne et al. [117] pointed out that social norms could enhance GPEB. They found that GPEB influenced hotel services, which was reciprocal as hotel services also affected GPEB through the reuse of hotel towels. Moreover, Tsagarakis et al. [118] interviewed 2308 international airport guests in Crete and Greece, and found that most of them would like to visit and revisit low-carbon hotels, and their GPEB could positively impact customer satisfaction. Furthermore, scholars have researched GPEB and hotels’ room prices. For instance, Sánchez et al. [58] found that although environmental protection measures increased the operation costs and room prices, some guests with eco-friendly values were willing to pay higher prices. Additionally, they found that guests were willing to revisit lodging that provided low-carbon services. In that case, GPEB has a positive effect on satisfaction and revisit rate.

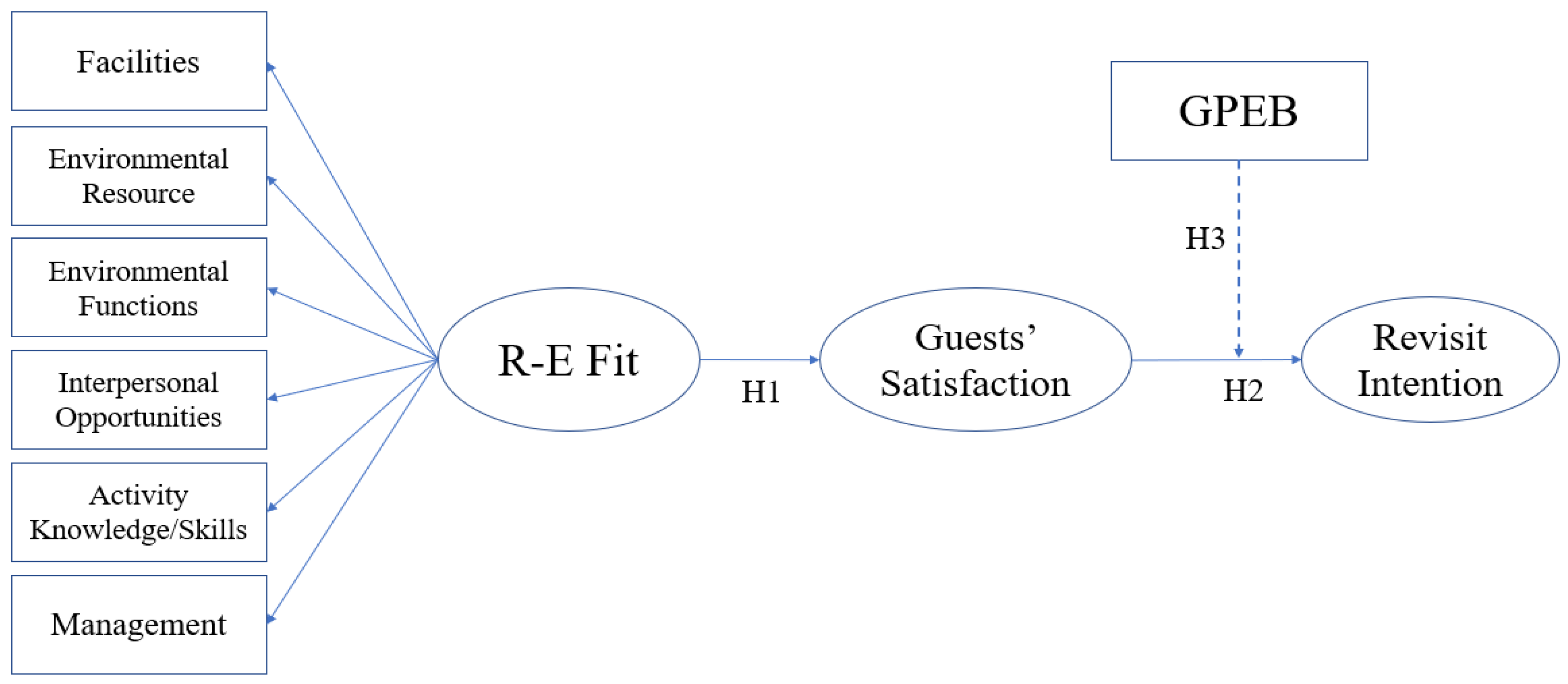

Figure 1 shows the model suggested by the hypothesized relationships between the constructs. The first route is concerned with the relationships among the R-E Fit, guests’ satisfaction, and guests’ revisit intention constructs. Understanding the importance of GPTB in low-carbon hospitality management, the second route focuses on the moderating effect of GPEB on the relationship between guests’ satisfaction and revisit intention.

Figure 1. Conceptual model. Note: R-E Fit Recreationist-Environmental Fit, GPEB guests’ pro-environmental behavior.

References

- Tan, S.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Lee, C.; Hashim, H.; Chen, B. A holistic low carbon city indicator framework for sustainable development. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1919–1930.

- Batle, J.; Orfila-Sintes, F.; Moon, C.J. Environmental management best practices: Towards social innovation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 14–20.

- Salehi, M.; Filimonau, V.; Asadzadeh, M.; Ghaderi, E. Strategies to improve energy and carbon efficiency of luxury hotels in Iran. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 1–15.

- Choi, H.M.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Agmapisarn, C. Hotel environmental management initiative (HEMI) scale development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 562–572.

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93.

- Tsai, K.T.; Lin, T.P.; Hwang, R.L.; Huang, Y.J. Carbon dioxide emissions generated by energy consumption of hotels and homestay facilities in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 13–21.

- Cop, S.; Alola, U.V.; Alola, A.A. Perceived behavioral control as a mediator of hotels’ green training, environmental commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior: A sustainable environmental practice. Bus Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3495–3508.

- Abuelhassan, A.E.; Elsayed, Y.N.M. The impact of employee green training on hotel environmental performance in the Egyptian hotels. Int. J. Recent Trends Bus. Tour 2020, 4, 24–33. Available online: https://ejournal.lucp.net/index.php/ijrtbt/article/view/943 (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Almomani, I.; Nasseef, M.A.; Bataine, F.; Ayoub, A. The effect of environmental preservation, advanced technology, hotel image and service quality on guest loyalty. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2017, 8, 49–64.

- Fraj, E.; Matute, J.; Melero, I. Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 30–42.

- El Shafey, H.; Hend, M.; Gad El Rab, M. Evaluating Environmental Management System Adoption in the First Class Hotels in Alexandria. Int. J. Herit. Tour. Hosp. 2018, 12, 332–349.

- Li, J.; Mao, P.; Liu, H.; Wei, J.; Li, H.; Yuan, J. Key Factors Influencing Low-Carbon Behaviors of Staff in Star-Rated Hotels—An Empirical Study of Eastern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8222.

- Yi, L. The analysis on carbon footprint of catering products in high-star hotels during operation: Based on investigation conducted in parts of high-star hotels in Ji’nan. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 890–894.

- Zhang, H. Empirical study on low-carbon development of Guangzhou hotels and catering enterprises. Pri. Mont. 2012, 3, 84–87.

- Four Seasons Malaysia Introduces Low-Carbon Spirits Program. Available online: https://travelandynews.com/four-seasons-malaysia-introduces-low-carbon-spirits-programme/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Small Measures in Detergents and High Profits (Shangri-La Hotel, Sanya). Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/dfQAplEA08PfzXYwvwZBzQ (accessed on 17 May 2019).

- The Green Light on the International Tourism Island—Hainan Guest Hotel’s Experience Sharing. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/sHCv9fo-9mgoQ5852iDIjA (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Moutinho, L. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism. Eur. J. Mark. 1987, 21, 5–44.

- Li, Q.; Wu, M. Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour in travel destinations: Benchmarking the power of social interaction and individual attitude. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1371–1389.

- Xu, F.; Huang, L.; Whitmarsh, L. Home and away: Cross-contextual consistency in tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1443–1459.

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, H. To buy or not to buy? The effect of time scarcity and travel experience on tourists’ impulse buying . Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103083.

- Tsaur, S.H.; Liang, Y.W.; Weng, S.C. Recreationist-environment fit and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 421–429.

- Zou, Y.G.; Meng, F.; Li, N.; Pu, E. Ethnic minority cultural festival experience: Visitor–environment fit, cultural contact, and behavioral intention. Tour. Econ. 2020, 27, 1237–1255.

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences OF INDIVIDUALS’FIT at work: A meta-analysis OF person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342.

- Wahl, H.W.; Fänge, A.; Oswald, F.; Gitlin, L.N.; Iwarsson, S. The home environment and disability-related outcomes in aging individuals: What is the empirical evidence? Gerontology 2009, 49, 355–367.

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49.

- Cable, D.M.; Edwards, J.R. Complementary and supplementary fit: A theoretical and empirical integration. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 822–834.

- Muchinsky, P.M.; Monahan, C.J. What is person-environment congruence? Supplementary versus complementary models of fit . J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 31, 268–277.

- Edwards, J.R. Person-Job Fit: A Conceptual Integration, Literature Review, and Methodological Critique; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991.

- Cable, D.M.; Judge, T.A. Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 294–311.

- Ghielen, S.T.S.; De Cooman, R.; Sels, L. The interacting content and process of the employer brand: Person-organization fit and employer brand clarity. Eur. J. Work Organ. 2021, 30, 292–304.

- Seong, J.Y.; Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Park, W.W.; Hong, D.S.; Shin, Y. Person-group fit: Diversity antecedents, proximal outcomes, and performance at the group level. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1184–1213.

- Tsaur, S.H.; Liang, Y.W.; Lin, W.R. Conceptualization and measurement of the recreationist-environment fit. J. Leis. Res. 2012, 44, 110–130.

- Chiang, Y.J. Perceived Restorativeness on Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Case of a Rice Field Landscape. Adv. Hosp. 2021, 17, 37–54.

- Chang, S.Y.; Tsaur, S.H.; Yen, C.H.; Lai, H.R. Tour member fit and tour member–leader fit on group package tours: Influences on tourists’ positive emotions, rapport, and satisfaction. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 42, 235–243.

- Liang, Y.W.; Peng, M.L. The relationship between recreationist–environment fit and recreationist delight. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 22, 62–75.

- Warren, C.; Becken, S.; Coghlan, A. Using persuasive communication to co-create behavioural change–engaging with guests to save resources at tourist accommodation facilities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 935–954.

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Buhalis, D. A model of perceived image, memorable tourism experiences and revisit intention. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 326–336.

- López-Gamero, M.D.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Claver-Cortes, E. The relationship between managers’ environmental perceptions, environmental management and firm performance in Spanish hotels: A whole framework. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 141–163.

- Rahman, M.; Moghavvemi, S.; Thirumoorthi, T.; Rahman, M.K. The impact of tourists’ perceptions on halal tourism destination: A structural model analysis. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 575–594.

- Mohaidin, Z.; Wei, K.T.; Murshid, M.A. Factors influencing the tourists’ intention to select sustainable tourism destination: A case study of Penang, Malaysia. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 442–465.

- Taylor, S.; Peacock, A.; Banfill, P.; Shao, L. Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from UK hotels in 2030. Build Environ. 2010, 45, 1389–1400.

- Dalton, G.; Lockington, D.; Baldock, T. A survey of tourist attitudes to renewable energy supply in Australian hotel accommodation. Renew. Energy 2008, 33, 2174–2185.

- Sato, Y.; Al-alsheikh, A. Comparative Analysis of the Western Hospitality and the Japanese Omotenashi: Case Study Research of the Hotel Industry. Bus. Account. Res. 2014, 1–15. Available online: http://kwansei-ac.jp/iba/assets/pdf/journal/BandA_review_December_14p1-16.pdf. (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Akincilar, A.; Dagdeviren, M. A hybrid multi-criteria decision making model to evaluate hotel websites. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 263–271.

- Dogru, T.; McGinley, S.; Kim, W.G. The effect of hotel investments on employment in the tourism, leisure and hospitality industries. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2020, 32, 1941–1965.

- Chung, K.C. Green marketing orientation: Achieving sustainable development in green hotel management. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 722–738.

- Chan, E.S. Influencing stakeholders to reduce carbon footprints: Hotel managers’ perspective. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102807.

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Dief, E.; Moustafa, M. A description of green hotel practices and their role in achieving sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–20.

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520.

- Chen, R.J. From sustainability to customer loyalty: A case of full service hotels’ guests. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 261–265.

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, J. Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tour Manag. 2019, 70, 430–443.

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Green image and consumers’ word-of-mouth intention in the green hotel industry: The moderating effect of Millennials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 426–436.

- Miao, L.; Wei, W. Consumers’ pro-environmental behavior and its determinants in the lodging segment. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 319–338.

- Moulay, A.; Ujang, N. Insight into the issue of underutilised parks: What triggers the process of place attachment? Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2021, 13, 1–20.

- Berezan, O.; Raab, C.; Yoo, M.; Love, C. Sustainable hotel practices and nationality: The impact on guest satisfaction and guest intention to return. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 227–233.

- Guo, L.; Xiao, J.J.; Tang, C. Understanding the psychological process underlying customer satisfaction and retention in a relational service. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 1152–1159.

- Sánchez-Medina, P.S.; Díaz-Pichardo, R.; Cruz-Bautista, M. Stakeholder influence on the implementation of environmental management practices in the hotel industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 387–398.

- Beatty, S.E.; Ogilvie, J.; Northington, W.M.; Harrison, M.P.; Holloway, B.B.; Wang, S. Frontline service employee compliance with customer special requests. J. Serv. Res. 2016, 19, 158–173.

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. A Framework for Marketing Management; Pearson: London, UK, 2016; p. 352.

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, D.; Kang, C.Y. The impact of high-performance work systems in the health-care industry: Employee reactions, service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 17–36.

- Lee, H.S. Major moderators influencing the relationships of service quality, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. Asian. Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 1–11. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.428.6730&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828.

- Han, H.; Ryu, K. The theory of repurchase decision-making (TRD): Identifying the critical factors in the post-purchase decision-making process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 786–797.

- Paulose, D.; Shakeel, A. Perceived Experience, Perceived Value and Customer Satisfaction as Antecedents to Loyalty among Hotel Guests. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 1–35.

- Hou, H.; Wu, H. Tourists’ perceptions of green building design and their intention of staying in green hotel. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 115–128.

- Barbulescu, A.; Moraru, A.D.; Duhnea, C. Ecolabelling in the Romanian seaside hotel industry—Marketing considerations, financial constraints, perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–13.

- Mjongwana, A.; Kamala, P.N. Non-financial performance measurement by small and medium sized enterprises operating in the hotel industry in the city of Cape Town. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–26. Available online: https://www.ajhtl.com/uploads/7/1/6/3/7163688/article_29_vol_7__1__2018.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand consumers’ intentions to visit green hotels in the Chinese context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2810–2825.

- Williams, D.A. Developing an Employee Training Addendum for a Sustainable Hospitality Operation. Master’s Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2011.

- Aksu, A.; Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Hotel customer segmentation according to eco-service quality perception: The case of Russian tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021; 1–17, ahead-of-print.

- Yusof, Y.; Awang, Z.; Jusoff, K.; Ibrahim, Y. The influence of green practices by non-green hotels on customer satisfaction and loyalty in hotel and tourism industry. Int. J. Green Econ. 2017, 11, 1–14.

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, P.B.; Cui, Y. Influence of choice architecture on the preference for a pro-environmental hotel. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 512–527.

- Song, Q.; Li, J.; Duan, H.; Yu, D.; Wang, Z. Towards to sustainable energy-efficient city: A case study of Macau. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2017, 75, 504–514.

- Tuan, L.T. Disentangling green service innovative behavior among hospitality employees: The role of customer green involvement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103045.

- Floričić, T. Sustainable solutions in the hospitality industry and competitiveness context of “green hotels”. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 1104–1113.

- Crespi, G.; Becchio, C.; Corgnati, S.P. Towards post-carbon cities: Which retrofit scenarios for hotels in Italy? Renew. Energy 2021, 163, 950–963.

- Ahn, J.; Kwon, J. Green hotel brands in Malaysia: Perceived value, cost, anticipated emotion, and revisit intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1559–1574.

- Meng, B.; Cui, M. The role of co-creation experience in forming tourists’ revisit intention to home-based accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100581.

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21.

- Mannan, M.; Chowdhury, N.; Sarker, P.; Amir, R. Modeling customer satisfaction and revisit intention in Bangladeshi dining restaurants. J. Model. Manag. 2019, 14, 922–947.

- Seetanah, B.; Teeroovengadum, V.; Nunkoo, R.S. Destination Satisfaction and Revisit Intention of Tourists: Does the Quality of Airport Services Matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 109634801879844.

- Stylos, N.; Bellou, V.; Andronikidis, A.; Vassiliadis, C.A. Linking the dots among destination images, place attachment, and revisit intentions: A study among British and Russian tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 15–29.

- Allameh, S.M.; Pool, J.K.; Jaberi, A.; Salehzadeh, R.; Asadi, H. Factors influencing sport tourists’ revisit intentions: The role and effect of destination image, perceived quality, perceived value and satisfaction. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2015, 27, 191–207.

- Brown, G.; Smith, A.; Assaker, G. Revisiting the host city: An empirical examination of sport involvement, place attachment, event satisfaction and spectator intentions at the London Olympics. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 160–172.

- Cham, T.H.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Will destination image drive the intention to revisit and recommend? Empirical evidence from golf tourism. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2021; ahead-of-print.

- Simpson, G.D.; Sumanapala, D.P.; Galahitiyawe, N.W.; Newsome, D.; Perera, P. Exploring motivation, satisfaction and revisit intention of ecolodge visitors. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 26, 359–379.

- Back, R.M.; Bufquin, D.; Park, J.Y. Why do they come back? The effects of winery tourists’ motivations and satisfaction on the number of visits and revisit intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 22, 1–25.

- Li, T.T.; Liu, F.; Soutar, G.N. Experiences, post-trip destination image, satisfaction and loyalty: A study in an ecotourism context. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100547.

- Loi, L.T.I.; So, A.S.I.; Lo, I.S.; Fong, L.H.N. Does the quality of tourist shuttles influence revisit intention through destination image and satisfaction? The case of Macao. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 32, 115–123.

- Liat, C.B.; Mansori, S.; Huei, C.T. The associations between service quality, corporate image, customer satisfaction, and loyalty: Evidence from the Malaysian hotel industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 314–326.

- Rasheed, M.I.; Okumus, F.; Weng, Q.; Hameed, Z.; Nawaz, M.S. Career adaptability and employee turnover intentions: The role of perceived career opportunities and orientation to happiness in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 98–107.

- Leonidou, L.C.; Christodoulides, P.; Kyrgidou, L.P.; Palihawadana, D. Internal drivers and performance consequences of small firm green business strategy: The moderating role of external forces. J. Bus. Ethics. 2017, 140, 585–606.

- Wu, H.C.; Ai, C.H.; Cheng, C.C. Synthesizing the effects of green experiential quality, green equity, green image and green experiential satisfaction on green switching intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 7, 366–389.

- Lee, B.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J.S. Dynamic nature of destination image and influence of tourist overall satisfaction on image modification. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 239–251.

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424.

- Moeller, T.; Dolnicar, S.; Leisch, F. The sustainability–profitability trade-off in tourism: Can it be overcome? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 155–169.

- Levinson, A. Energy efficiency standards are more regressive than energy taxes: Theory and evidence. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 6, S7–S36.

- Wynes, S.; Nicholas, K.A. The climate mitigation gap: Education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 074024.

- Trang, H.L.T.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, H. How do green attributes elicit pro-environmental behaviors in guests? The case of green hotels in Vietnam. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 14–28.

- Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M.; Boley, B.B. Modeling the psychological antecedents to tourists’ pro-sustainable behaviors: An application of the value-belief-norm model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 957–972.

- Orsato, R.J. Sustainability Strategies: When Does it Pay to be Green? Springer; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 3–22.

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Are consumers willing to pay more for green practices at restaurants? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 329–356.

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33.

- Zdravković, S.; Peković, J. The analysis of factors influencing tourists’ choice of green hotels. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 8, 69–78.

- Wang, L.; Wong, P.P.W.; Narayanan Alagas, E.; Chee, W.M. Green hotel selection of Chinese consumers: A planned behavior perspective. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 15, 192–212.

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. What influences water conservation and towel reuse practices of hotel guests? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 87–97.

- Dani, R.; Tiwari, K.; Negi, P. Ecological approach towards sustainability in hotel industry. Mater. Today 2021, 46, 10439–10442.

- Han, H.; Hwang, J. Cruise travelers’ environmentally responsible decision-making: An integrative framework of goal-directed behavior and norm activation process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 94–105.

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Lee, J.S.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355.

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P.; Novotna, E. International hotel chains and environmental protection: An analysis of Hilton’s we care! programme (Europe, 2006–2008). J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 797–816.

- Al-Aomar, R.; Hussain, M. An assessment of green practices in a hotel supply chain: A study of UAE hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 32, 71–81.

- Tan, L.L.; Abd Aziz, N.; Ngah, A.H. Mediating effect of reasons on the relationship between altruism and green hotel patronage intention. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 18–30.

- Kim, A.; Kim, K.P.; Nguyen, T.H.D. The Green Accommodation Management Practices: The Role of Environmentally Responsible Tourist Markets in Understanding Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2326.

- Lee, J.S.; Hsu, L.T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914.

- Yadav, R.; Dokania, A.K.; Pathak, G.S. The influence of green marketing functions in building corporate image. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2178–2196.

- Scheibehenne, B.; Jamil, T.; Wagenmakers, E.J. Do descriptive social norms enhance pro-environmental behavior? A bayesian reanalysis of hotel towel reuse. Adv. Consum. Res. 2016, 44, 610–611. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v44/acr_vol44_1022097.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Tsagarakis, K.P.; Bounialetou, F.; Gillas, K.; Profylienou, M.; Pollaki, A.; Zografakis, N. Tourists’ attitudes for selecting accommodation with investments in renewable energy and energy saving systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1335–1342.

More