Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by LIGIA RUSU.

Distancing and confinement at home during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has led to worsening of motor and cognitive functions, both for healthy adults and for patients with neurodegenerative diseases. The decrease in physical activity, the cessation of the intervention of the recovery and the social distance imposed by the lockdown, has had a negative impact on the physical and mental health, quality of life, daily activities, as well as on the behavioral attitudes of the diet.

- pandemic COVID-19

- neurodegenerative diseases

- physical activity

1. Introduction

A novel coronavirus named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and the disease called COVID-19, detected in China in December 2019, managed to affect over 200 countries in just 6 months, reporting over 10 million illnesses and over half a million deaths. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic in March 2020, thus causing worldwide concern. Therefore, all societies affected by the SARS-CoV-2 infection have gradually declared social distancing and home-confinement to prevent the spread of the new infection. According to Tondo et al. [1], the COVID-19 pandemic generates substantial changes in routine activities, restrictions of movement and has a considerable impact on people’s psychological and cognitive levels. Furthermore, it creates challenges for the healthcare system. The main problems in dementia during this pandemic period are related to an increase of sufferers of cognitive impairment [1].

Under these conditions, the most drastic quarantine measures in human history were imposed [2]. This situation, imposed to slow the spread of COVID-19, has had negative effects on the quality of life, psychosocial and emotional behavior of individuals, even whether apparently healthy or with various associated diseases.

Due to social isolation and lack of direct communication, changes in emotional status have been reported, with the appearance of emotional disorders by way of feelings of loneliness, decreased personality (e.g., frustration, boredom, delusions, inadequate supplies) and distrust of peers [3,4,5][3][4][5].

Infection with SARS-CoV-2, which has caused severe acute respiratory syndrome and other distress for multiple organ failure, has affected a substantial number of patients with other comorbidities (such as Myasthenia Gravis, Vascular dementia) associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease, Frontotemporal dementia and Lewy body disease. Lack of therapeutic interventions, limiting access to specialized treatments, decreasing physical activity and help from caregivers and family during this period has aggravated functional abilities, cognitive impairments and behavioral disturbances [6].

During the isolation at home imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the needs for social assistance intervention increased, putting pressure on professional healthcare and home caregivers for patients with dementia [5]. Therefore, the imposed home confinement considerably restricted access to social and health services, which led to a worsening of behavioral and neuropsychological symptoms for them [6]. At the same time, a decrease in physical activity and limit of activity daily living (ADL), generate a change of lifestyle and life quality.

From this point of view, the promotion of a mental health and wellbeing lifestyle, involves continuing physical training. This means supporting movement skills, improving gait, increasing muscle strength and endurance, and prevents the progression of the disease in mild cognitive impairments (MCI). The challenge identified in the literature is that the COVID-19 outbreak has limited access to these activities due to isolation at home [7]. Hence, other interventions, such as aerobic exercises and home dance training had to be implemented to counteract the progressive deficiencies of patients with PD [8,9][8][9].

In addition to worsening motor and cognitive functions, the COVID-19 quarantine also impaired sleep quality, eating behavior affected mental wellbeing and induced depressive symptoms [10].

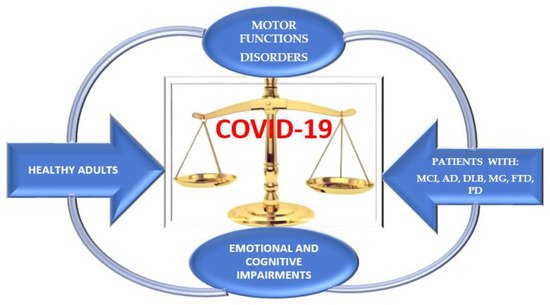

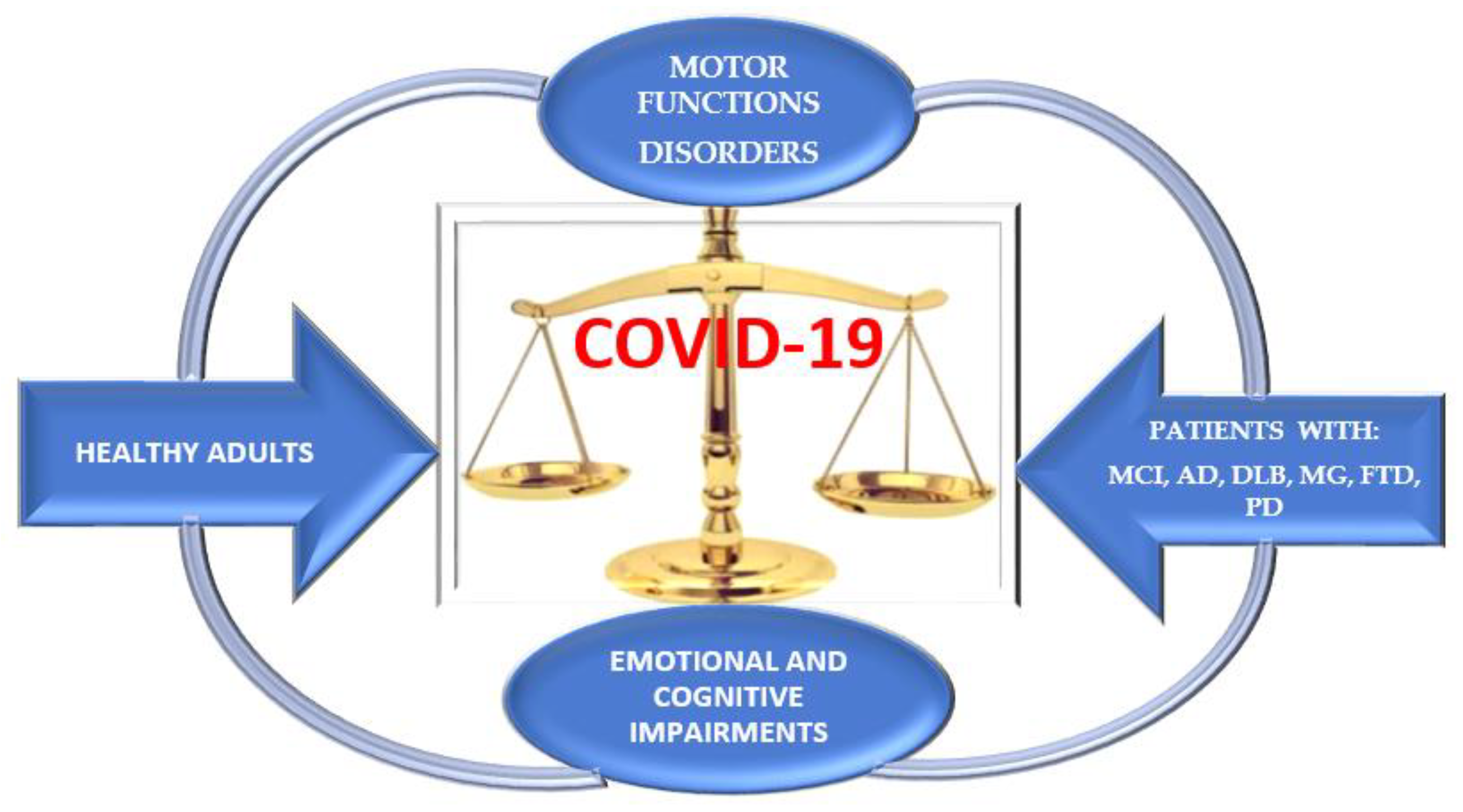

In the context of the COVID-19 outbreak, the need for modern digital therapies and those that are delivered remotely as well as their intervention at home have proven to be effective in the rehabilitation of patients with PD and other neurodegenerative disease. This could decrease the effect of motor skills, gait pattern, neuropsychiatric impairments and classic symptoms, such as tremor, bradykinesia, postural instability and freezing of gait [11]. The aim of the paper is to carry out a literature analyses regarding how the lockdown and physical activity influence motor and cognitive function, based on evaluation of the impact of decreasing physical activity, and the affected emotional status of healthy adults and patients with neurodegenerative diseases and associated comorbidities, such as Myastenia and Vascular dementia, in conditions imposed by COVID-19. The aim of the literature analysis includes a review of how the new interventions, such as telemedicine and telerehabilitation, could improve or maintain a healthy status, based on multi-language online surveys, semi-structured interviews and interventions on smartphones delivered through online platforms, for instance, Google, WhatsApp, Twitter, Research Gate, Facebook and LinkedIn.

2. New Recovery Strategies in Motor and Cognitive Functions

The purpose of qualitative screening was to demonstrate the negative impact on the motor outcomes and on the emotional and psychological functions [3] of the isolation period at home as well as the subsequent restrictions imposed by the fight against the spread of the new coronavirus infection on healthy adults but also of patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as: Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’ disease, Lewy body disease, and associated diseases (Vascular dementia, Myasthenia gravis), Frontotemporal dementia [6]. Through technological communication systems, such as intervention smartphones and online platforms (Google online, Instagram, Facebook, Tik Tok, Snapchat, WhatsApp, ResearchGate, Twitter, LinkedIn) semi-structured questionnaires had been delivered, online interviews in surveys in multiple languages [13,14,15,16][12][13][14][15]. In the largest online study for the COVID-19 outbreak, ECBL was conducted in Africa (40%), Asia (36%) and Europe (21%), before and after lockdown, and discussed in four trials [13[12][13][14][15],14,15,16], in multiple languages. The physical activities performed included exercise classes, or gym classes, walking training, workouts of different intensity (slow, moderate or vigorous intensity, outdoor and indoor physical activity and ADL). The results obtained were interpreted by IPAQ-SF and STBQL and demonstrated in general, declining ongoing weekly physical activity in terms of duration, power and endurance. In terms of ADLs, these were moderate in frequency and velocity [13,14,15,16][12][13][14][15]. However, there have been challenges in supporting physical activities at home, organizing online exercise groups for performing exercise patterns delivered through questionnaires or telerehabilitation interventions, including training with different intensities and that which is ongoing (such as carried out weekly) as well as in providing support [8,19][8][16]. Another study showed that increase of daily physical activities in young people with the diversification of actions, especially food-related actions, allowed for improvement in the diets for adolescents in lockdown compared to the period of direct participation in social life [18][17]. The most significant changes were related to accentuation, the cognitive function disorders and emotional status, impaired wellbeing quality of life, sleep and unhealthy eating behaviors. The quantification of the outcomes was measured by the instruments: SWEMWBS, SMFQ, SLSQOL, SSPQOL, PSQI and SDBQL, which reported worsening wellbeing and satisfaction of life, increasing mental tensions related to quality of life, depression symptoms, anxiety, lack of communication, enhanced sleep impairments, mental disorders and bad feelings [2,5,9,13][2][5][9][12]. More pronounced changes in emotional status and mental wellbeing were found especially in women. Most of the mental and emotional disorders occurred as a result of the cessation of professional activities, lack of communication and socialization, imposed by combating the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 infection by respecting the rules of social distancing. Along with these came unhealthy eating habits, with the increase in the number of daily meals, rich in fat, carbohydrates and low in protein, excessive alcohol consumption and smoking, which led to weight gain, increased functional disorders and exposure to future morbidity [5,6,25][5][6][18]. Patients with neurodegenerative diseases carrying out different types of physical activities: dance and fitness training, yoga, walking workout, light, moderate or high intensity aerobic exercise and daily activities for living, showed improvements in cardiovascular function, physical performance of the gait pattern, speed and length of the step and balance as well as delays in the decline of motor skills [10,23,35][10][19][20]. Regarding PD patients with improved cardiovascular function, the physical performance of the gait pattern, the dysfunctions of the four cardinal points of the disease, namely, tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability, have been shown to be delayed in their evolution by sustained and correctly performed physical exercises [10,20][10][21] with instructions from online platforms, and in some situations, supervised by specialist therapists through video applications. However, in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [33][22], Lewy body dementia [34][23], or Frontotemporal dementia and associated Myasthenia Gravis or those with Vascular dementia, who no longer received institutionalized care with therapists but caregivers at home or through information and communication technology that delivered instructions with physical activity programs, there were obvious declines in motor dysfunctions. In these situations, caregivers at home have also been observed to worsen their motor performance by decreasing the physical training and the motor rehabilitation patterns that were imposed on their patients and in which they directly participated. On the other hand, apart from the degradation of the motor functions, the most significant dysfunctions were registered in the sphere of the cognitive functions and of the neuropsychic, affective and emotional status of both patients and their caregivers [38][24]. Moreover, the marked disturbances in the sleep/wake circadian rhythm as well as the behavioral changes in the home confinement period, determined the progressive decline in quality of lifestyle, satisfaction and mental wellbeing as affective disorders with depression, sadness, anxiety and feelings of loneliness that reflected lack of socialization from organized communities to emotional rehabilitation programs [40,41][25][26]. In addition to COVID-19 as a secondary stressor to the primary stressor, cognitive dysfunction, negative emotions, frustration and mental disorders had been exacerbated. The cognitive tools through their scores, used clearly, showed an increase in neuropsychiatric symptoms with worsening of depressive symptoms, anxiety and reduced mental wellbeing and speech neurocognitive tasks (MMSE, MoCA, GDS, PASE, HADS, QOL, etc.) [14,15][13][14]. Impairment of motor and cognitive status has been shown to be similar, in both healthy adults and patients with neurodegenerative pathology during isolation at home (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dynamic of motor and cognitive impairments in healthy adults and patients with neurodegenerative diseases.

Figure 1. Dynamic of motor and cognitive impairments in healthy adults and patients with neurodegenerative diseases.References

- Tondo, G.; Sarasso, B.; Serra, P.; Tesser, F.; Comi, C. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Cognition of People with Dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4285.

- Thabrew, H.; Stasiak, K.; Bavin, L.M.; Frampton, C.; Merry, S. Validation of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) and Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. Int. J. Meth. Psych. Res. 2018, 27, e1610.

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 10227, 912–920.

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Wisco, B.E.; Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking Rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 3, 400–424.

- Shah, N.; Cader, M.; Andrews, B.; McCabe, R.; Stewart-Brown, S.L. Evaluating and establishing the national norms for mental well-being using the short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1129–1144.

- Cagnin, A.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Marra, C.; Bonanni, L.; Cupidi, C.; Laganà, V.; Rubino, E.; Vacca, A.; Provero, P.; Isella, V.; et al. Behavioral and psychological effects of coronavirus disease-19 quarantine in patients with dementia. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 578015.

- Bentlage, E.; Ammar, A.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Brach, M. Practical Recommendations for Maintaining Active Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6265.

- Grande, A.J.; Keogh, J.; Silva, V.; Scott, A.M. Exercise versus no exercise for the occurrence, severity, and duration of acute respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD010596.

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short from (PAQ-SF): A systematic review. Int. J. Behov. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 115.

- Suzuki, K.; Numao, A.; Komagamine, T.; Haruyama, Y.; Kawasaki, A.; Funakoshi, K.; Fujita, H.; Suzuki, S.; Okamura, M.; Shiina, T.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers: A single-center survey in Tochigi prefecture. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 11, 1047–1056.

- Ellis, T.D.; Earhart, G.M. Digital therapeutics in Parkinson’ disease: Practical application and future potential. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 11 (Suppl. S1), S95–S101.

- Ammar, A.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Trabelsi, K.; Masmoudi, L.; Brach, M.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. COVID-19 Home confinement negatively impacts social participation and life satisfaction: A worldwide multicenter study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6237.

- Ammar, A.; Mueller, P.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Brach, M.; Schmicker, M.; Bentlage, E.; et al. Psychological consequences of COVID-19 home confinement: The ECBL-COVID 19 Multicenter Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240204.

- Ammar, A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Nutrients. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID 19 international online survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583.

- Ammar, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Brach, M.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Effects on home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Insights from the ECBL -COVID 19 multicentre study. Biol. Sport 2021, 38, 9–21.

- Ammar, A.; Boukhris, O.; Halfpaap, N.; Labott, B.K.; Langhans, C.; Herold, F.; Grässler, B.; Müller, P.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; et al. Four weeks of detraining induced by COVID-19 reverse cardiac improvements from eight weeks of fitness-dance training in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5930.

- Salzano, G.; Passanisi, S.; Pira, F.; Sorrenti, L.; La Monica, G.; Pajno, G.B.; Pecoraro, M.; Lombardo, F. Quarantine due to COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of adoleccents: The crucial role of tehnology. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 40.

- Rodrigues de Paula, F.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.F.; de Morais, C.; Faria, D.; Rocha de Brito, P.; Cardoso, F. Impact of an exercise program on physical, emotional, and social aspects of quality of life of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 1073–1077.

- Rodrigues-de-Paula, F.; Lana, R.D.C.; Lopes, L.K.R.; Cardoso, F.; Lindquist, A.R.R.; Piemonte, M.E.P.; Correa, C.L.; Israel, V.L.; Mendes, F.; Lima, L.O. Determinants of the use of physiotherapy services among individuals with Parkinson’s disease living in Brazil. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2018, 76, 592–598.

- Chen, Z.C.; Liu, S.; Gan, J.; Ma, L.; Du, X.; Zhu, H.; Han, J.; Xu, J.; Wu, H.; Fei, M.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’ disease and dementia with Lewy bodies in China: A 1-year follow -up study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 711658.

- Frazzitta, G.; Maestri, R.; Ferrazzoli, D.; Riboldazzi, G.; Bera, R.; Fontanesi, C.; Rossi, R.P.; Pezzoli, G.; Ghilardi, M.F. Multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment improves sleep quality in Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Mov. Disord. 2015, 2, 11.

- Müller, P.; Achraf, A.; Zou, L.; Apfelbacher, C.; Erickson, K.I.; Müller, N.G. COVID-19, physical (in-) activity, and dementia prevention. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 6, e12091.

- Zucca, M.; Isella, V.; Lorenzo, R.D.; Marra, C.; Cagnin, A.; Cupidi, C.; Bonanni, L.; Laganà, V.; Rubino, E.; Vanacore, N.; et al. Being the family caregiver of a patient with dementia during the coronavirus disease 2019 lockdown. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 653533.

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396.

- Templeton, J.M.; Poellabauer, C.; Schneider, S. Negative effects of COVID-19 stay-at-home mandateson physical intervention outcomes: A preliminary study. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 11, 1067–1077.

- Trabelsi, K.; Ammar, A.; Masmoudi, L.; Boukhris, O.; Chtourou, H.; Bouaziz, B.; Brach, M.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Sleep quality and physical activity as predictors of mental wellbeing variance in older adults during COVID-19 lockdown: ECLB COVID-19 international online survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4329.

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ball, R.; Ciervo, C.A.; Kabat, M. Use of the beck anxiety and depression inventories for primary care with medical outpatients. Assessment 1997, 4, 211–219.

- Balci, B.; Aktar, B.; Buran, S.; Tas, M.; Colakoglu, D.B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, anxiety, and depression in patients with Parkinson’ s disease. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2021, 44, 173–176.

- van der Heide, A.; Meinders, M.J.; Bloem, B.R.; Helmich, R.C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological distress, physical activity, and symptom severity in Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 10, 1355–1364.

More