The advancement of natural-based biomaterials in providing a carrier has revealed a wide range of benefits in the biomedical sciences, particularly in wound healing, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Incorporating nanoparticles within polymer composites has been reported to enhance scaffolding performance, cellular interactions and their physico-chemical and biological properties in comparison to analogue composites without nanoparticles. Combining therapies consisting of nanoparticles and biomaterials could be promising for future therapies and better outcomes in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

- nanoparticles

- nanotechnology

- natural biomaterials

- mechanisms

- cells

- signaling pathways

- regenerative medicine

- wound healing

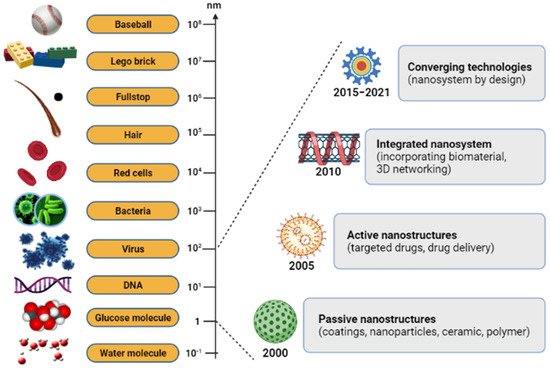

1. Introduction

2. Biological Cellular Effects and Signaling Pathways

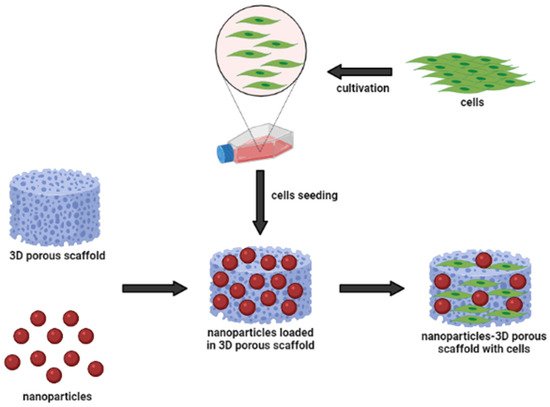

There has been increasing evidence that the biological properties of the scaffold affect various types of cellular behavior, including cell compatibility, viability, proliferation, and migration [104][37]. To address another important pathway of nanoparticle-incorporated biomaterials towards skin penetration, Kumar et al. [105][38] discussed the outcomes of using natural compound particles with incorporated biomaterials in skin tissue engineering applications. Based on available knowledge from the findings, the researchers used nanoparticles as carriers, due to their biological, electrical, mechanical and antibacterial properties [36]. As nanoparticles are implanted in the scaffold, it was found to develop the cytocompatibility of the particle substitute material and provide an appropriate surface morphology to enhance cellular functions. The biocompatibility and porous structure of scaffolds allow the cells to adhere to the surface of the scaffold effectively. Biological assays, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and MTT 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays, showed the proper cell attachment and proliferation of the prepared scaffolds. Both MTT and LDH assays are indirect tests known as the primary method for determining the toxicity of compounds with the scaffold, and number of damaged cells released into the culture media, respectively [26].

Due to special distributions of incorporated nanoparticles within the scaffolds in skin tissues, scientists also studied the effect of nanoparticles on cell proliferation and migration to skin cells. In the application of wound healing, recent studies based on the in vitro scratch experiments and in vivo animal studies have demonstrated positive results. The incorporation of nanoparticles into natural-based polymeric biomaterials significantly promoted cell proliferation and migration, which are the biological functions crucial for wound site closure, as well as restoration of barrier function [106,107,108][39][40][41]. The authors shared their findings, indicating that the cell migration path in the scratch area was shortened, and the migration rate increased after using their scaffoldings, which demonstrated excellent performance. These have shown that nanoparticles can act as a biological molecule; meanwhile natural-based biomaterials can be used as a substrate for cell growth, stimulating proliferation and migration. Accordingly, nanoparticles themselves promoted the proliferation and migration of human epidermal cells and human fibroblasts in vitro. Their proliferative-promoting effect always depends on their concentration and duration of action [109][42]. In addition, the combined application of nanoparticles and biomaterials had a synergistic promoting effect on human epidermal cell proliferation and wound healing. This is possible due to the scaffolds, which can absorb wound exudate and maintain a moist environment, necessary for cellular proliferation at the wound site. After these discoveries, the hydrophilic nature of the natural-based biomaterials’ polymer matrix characteristics was shown to be close to the value of fibroblast proliferation and migration [110][43].

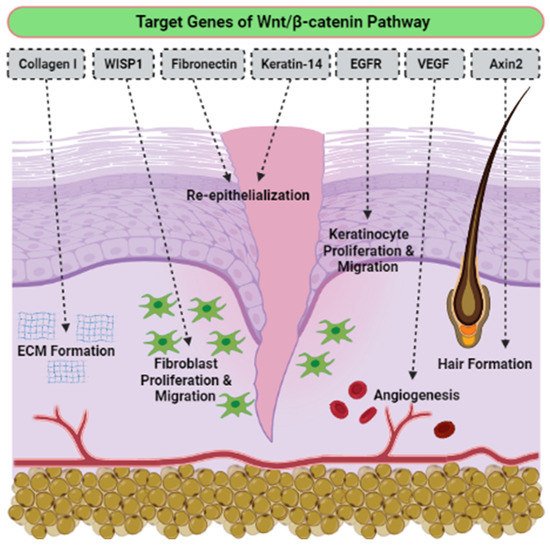

Even tThough there is no determination of signaling pathways in the selected articles, we have accumulated evidence of the activatioe activation signaling pathways that are critically involved in proliferation, migration cells, and wound healing. To the best of our knowledge, the he activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a vital role in the proliferative phase of wound healing and tissue regeneration after injury. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is activated in the dermis of the wound bed immediately after skin injury. β-catenin is a subunit of the cadherin protein complex, where Wnt plays a specific role in the regulation of β-catenin function [111,112,113][44][45][46]. The signaling of Wnt is mediated by multi-protein complexes together, which consist of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3β), Axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and casein kinase 1 (CK1) in the cytoplasm. Several target genes have been identified in cutaneous wound healing, as listed in Table 41. The Wnt/β-catenin activation pathway transcriptionally induces target genes such as Collagen I, Axin2, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Fibronectin, Keratin-14, VEGF and WISP1 during the wound repair process (Figure 63). Essentially, different Wnt/β-catenin signaling target genes contribute to the various events that occur during wound healing. For example, EGFR regulates the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes; meanwhile, collagen-1 plays a role in ECM formation. The up-regulation or rearrangement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhances the proliferation and migration of dermal fibroblasts, thus making them into distinct myofibroblasts. Therefore, it helps to reduce the surface area of the growing scar. Furthermore, the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway not only significantly facilitates migration and differentiation of keratinocytes in the epidermal layer, but it also induces angiogenesis and epithelial remodeling, which directly enhances skin wound healing [114,115][47][48].

| Wnt Target Genes | Role in Wound Healing |

|---|

| Axin2 | Hair formation through activation of hair follicles |

| Collagen I | Key protein of ECM synthesized during the proliferative phase |

| Collagen III | Key protein of ECM synthesized during the early proliferative phase |

| EGFR | Regulation of keratinocyte migration to wound bed |

| Endothelin-1 | Regulation of fibrosis and calcification |

| Fibronectin | ECM formation and re-epithelialization |

| Keratin-14 | Re-epithelialization |

| VEGF | Stimulation of angiogenesis |

| WISP1 | Promotion of dermal fibroblast proliferation and migration |

On the other hand, the TGF-β pathway is also involved in skin wound healing and dermal fibrosis. It is elaborated differently in the regulation of healing rate, which depends on the isoforms [116][49]. For example, TGF-β1 acts as a fibrosis stimulant factor; meanwhile, TGF-β3 regulates anti-scar activity. In adulthood and embryonic development, the Notch pathway controls epidermal cell differentiation [117][50], maintains skin homeostasis, and promotes angiogenesis [118,119,120][51][52][53]. A previous study reported that the activation of the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway is required, and sufficient for hair follicle neogenesis (HFN) [121][54]. Nevertheless, the need for Shh regulation may differ in the development of embryonic hair follicles (HF) and adult HFN. If epithelial Wnts are sufficient for embryonic HF development, both epithelial and dermal Wnts are still required for adult HFN [122,123][55][56]. Thus, targeting activated signaling pathways could provide an effective therapeutic approach for regenerative skin wound healing.

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

References

- Bayda, S.; Adeel, M.; Tuccinardi, T.; Cordani, M.; Rizzolio, F. The history of nanoscience and nanotechnology: From chemical-physical applications to nanomedicine. Molecules 2020, 25, 112.

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931.

- Kaur, P.; Luthra, R. Silver nanoparticles in dentistry: An emerging trend. SRM J. Res. Dent. Sci. 2016, 7, 162–165.

- Mahor, A.; Prajapati, S.K.; Verma, A.; Gupta, R.; Singh, T.R.R.; Kesharwani, P. Development, in-vitro and in-vivo characterization of gelatin nanoparticles for delivery of an anti-inflammatory drug. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 36, 55–61.

- Gnach, A.; Lipinski, T.; Bednarkieicz, A.; Rybka, J.; Capobianco, J.A. Upconverting nanoparticles: Assessing the toxicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1561–1584.

- Fadilah, N.I.M.; Ahamd, H.; Rahman, M.F.A.; Rahman, N.A. Electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibers doped with mesoporous silica nanoparticles for controlled release of hydrophilic model drug. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2019, 23, 212–218.

- Jeevanandam, J.; Barhoum, A.; Chan, Y.S.; Dufresne, A.; Danquah, M.K. Review on nanoparticles and nanostructured materials: Histroy, sources, toxicity and regulations. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 1050–1074.

- Fathi-Achachelouei, M.; Knopf-Margues, H.; Ribeiro da Silva, C.E.; Barthes, J.; Bat, E.; Tezcaner, A.; Vrana, N.E. Use of nanoparticles in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 113–135.

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, P.; Fu, Z.; Meng, S.; Dai, L.; Yang, H. Applications of nanomaterials in tissue engineering. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 19041.

- Kamoun, E.A.; Loutfy, S.A.; Hussein, Y.; Kenawy, E.S. Recent advances in PVA-polysaccharide based hydrogels and electrospun nanofibers in biomedical applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 187, 755–768.

- Lickmichand, M.; Shaji, C.S.; Valarmathi, N.; Benjamin, A.S.; Kumar, R.K.; Nayak, S.; Saraswathy, R.; Sumathi, S.; Arunai, N.R.N. In Vitro biocompatibility and hyperthermia studies on synthesized cobalt ferrite nanoparticles encapsulated with polyethylene glycol for biomedical applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 15, 252–261.

- Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, K.N. The effect of CaCO3 nanoparticles and chitosan on the properties of PLA based biomaterials for biomedical applications. Encycl. Renew. Sustain. Mater. 2020, 2, 736–745.

- Torgbo, S.; Sukyai, P. Biodegradation and thermal stability of bacterial cellulose as biomaterial: The relevance in biomedical applications. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 179, 109232.

- Liu, X.; Zheng, C.; Luo, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, H. Recent advances of collagen-based biomaterials: Multi-hierarchical structure, modification and biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 1509–1522.

- Lo, S.; Fauzi, M.B. Current update of collagen nanomaterials-fabrication, characterization and its applications: A review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 316.

- El Fawal, G.; Hong, H.; Mo, X.; Wang, H. Fabrication of scaffold based on gelatin and polycaprolactone (PCL) for wound dressing application. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 102501.

- Hu, B.; Guo, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Ding, F. Recent advances in chitosan-based layer-by-layer biomaterials and their biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 271, 118427.

- Patil, P.P.; Reagen, M.R.; Bohara, R.A. Silk fibroin and silk-based biomaterial derivatives for ideal wound dressings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4613–4627.

- Ucar, B. Natural biomaterials in brain repair: A focus on collagen. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 146, 105033.

- Zulkiflee, I.; Fauzi, M.B. Gelatin-polyvinyl alcohol film for tissue engineering: A concise review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 979.

- Sun, J.; Tan, H. Alginate-based biomaterials for regenerative medicine applications. Materials 2013, 6, 1285–1309.

- Lee, C.H.; Singla, A.; Lee, Y. Biomedical application of collagen. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 221, 1–22.

- Kalashnikova, I.; Das, S.; Seal, S. Nanomaterials for wound healing: Scope and advancement. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2593–2612.

- Akrami-Hasan-Kohal, M.; Eskandari, M.; Solouk, A. Silk fibroin hydrogel/dexamethasone sodium phosphate loaded chitosan nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery system. Colloids Surf. B 2021, 205, 111892.

- Huang, J.; Ren, J.; Chen, G.; Deng, Y.; Wang, G.; Wu, X. Evaluation of the xanthan-based film incorporated with silver nanoparticles for potential application in the non-healing infectious wound. J. Nanomater. 2017, 2017, 6802397.

- Kumar, S.S.D.; Rajendran, N.K.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. Recent advances on silver nanoparticle and biopolymer-based biomaterials for wound healing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 165–175.

- Nekounam, H.; Kandi, M.R.; Shaterabadi, D.; Samadian, H.; Mahmoodi, N.; Hasanzadeh, E.; Faridi-Majidi, R. Silica nanoparticles-incorporated carbon nanofibers as bioactive biomaterial for bone tissue engineering. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 115, 108320.

- Bapat, R.A.; Chaubal, T.V.; Joishi, C.P.; Bapat, P.R.; Choudhury, H.; Pandey, M.; Gorain, B.; Kesharwani, P. An overview of application of silver nanoparticles for biomaterials in dentistry. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 91, 881–898.

- Bapat, R.A.; Chaubal, T.V.; Dharmadhikari, S.; Abdulla, A.M.; Bapat, P.; Alexander, A.; Dubey, S.K.; Kesharwani, P. Recent advances of gold nanoparticles as biomaterial in dentistry. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 586, 119596.

- Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, F.; Xu, Z.; Dai, F.; Liu, W. An injectable supramolecular polymer nanocomposite hydrogel for prevention of breast cancer recurrence with theranostic and mammoplastic functions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1801000.

- Mousa, M.; Evans, N.D.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Dawson, J.I. Clay nanoparticles for regenerative medicine and biomaterial design: A review of clay bioactivity. Biomaterials 2018, 159, 204–214.

- Sebastiammal, S.; Fathima, A.S.L.; Devanesan, S.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Henry, J.; Govindarajan, M.; Vaseeharan, B. Curcumin-encased hydroxyapatite nanoparticles as novel biomaterials for antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer applications: A perspective of nano-based drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 101752.

- Zengin, A.; Sutthavas, P.; Rijt, S.V. Inorganic nanoparticle-based biomaterials for regenerative medicine. In Nanostructured Biomaterials for Regenerative Medicine; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 293–312.

- Liu, Y.; Shi, J. Antioxidative nanomaterials and biomedical applications. Nano Today 2019, 27, 146–177.

- Padmanabhan, J.; Kyriakides, T.R. Nanomaterials, inflammation and tissue engineering. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 7, 355–370.

- Hasan, A.; Morshed, M.; Memic, A.; Hassan, S.; Webster, T.J.; El-Sayed Marei, H. Nanoparticles in tissue engineering: Applications, challenges and prospects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 5637.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Yu, X.; Wang, H.; Bai, Z.; Jiang, Y.C.; Li, X.; et al. Endothelial cell migration regulated by surface topography of poly (ε-caprolactone) nanofibers. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 4959–4970.

- Kumar, S.S.D.; Abrahamse, H. Advancement of nanobiomaterials to deliver natural compounds for tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6752.

- Ehterami, A.; Salehi, M.; Farzamfar, S.; Vaez, A.; Samadian, H.; Sahrapeyma, H.; Mirzaii, M.; Ghorbani, S.; Goodarzi, A. In vitro and in vivo study of PCL/COLL wound dressing loaded with insulin-chitosan nanoparticles on cutaneous wound healing in rats model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 601–609.

- Balakrishnan, S.B.; Kuppu, S.; Thambusamy, S. Biologically important alumina nanoparticles modified polyvinylpyrrolidone scaffolds in vitro characterizations and it is in vivo wound healing efficacy. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1246, 131195.

- Zhang, M.; Wang, G.; Wang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Meng, W.; Zhang, X.; Du, F.; Lee, S. chitosan nanoparticle and polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate/chitosan bilayer dressing for wound healing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 175, 481–494.

- Galandakova, A.; Frankova, J.; Ambrozova, N.; Habartova, K.; Pivodova, V.; Zalesak, B.; Safarova, K.; Smekalova, M.; Ulrichova, J. Effects of silver nanoparticles on human dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2016, 35, 946–957.

- Azlan, A.Y.H.N.; Katas, H.; Busra, M.F.M.; Salleh, N.A.M.; Smandri, A. Metal nanoparticles and biomaterials: The multipronged approach for potential diabetic wound therapy. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2021, 10, 653–670.

- Yang, H.S.; Tsai, Y.C.; Korivi, M.; Chang, C.T.; Hseu, Y.C. Lucidone promotes the cutaneous wound healing process via activation of the PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1864, 151–168.

- Cheon, S.S.; Cheah, A.Y.; Turley, S.; Nadesan, P.; Poon, R.; Clevers, H.; Alman, B.A. β-catenin stabilization dysregulates mesenchymal cell proliferation, mortility, and invasiveness and causes aggressive fibromatosis and hyperplastic cutaneous wounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 6973–6978.

- Clevers, H.; Nusse, R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 1192–1205.

- Houschyar, K.S.; Momeni, A.; Pyles, M.N.; Maan, Z.N.; Whittam, A.J.; Siemers, F. Wnt signaling induces epithelial differentiation during cutaneous wound healing. Organogenesis 2015, 11, 95–104.

- Birdsey, G.M.; Shah, A.V.; Dufton, N. The endothelial transcription factor ERG promotes vascular stability and growth through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Dev. Cell 2015, 32, 82–96.

- Bielefeld, K.A.; Amini-Nik, S.; Alman, B.A. Cutaneous wound healing: Recruiting developmental pathways for regeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 2059–2081.

- Blanpain, C.; Fuchs, E. Epidermal homeostasis: A balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 10, 207–217.

- Okuyama, R.; Tagami, H.; Aiba, S. Notch signaling: Its role in epidermal homeostasis and in the pathogenesis of skin diseases. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008, 49, 187–194.

- Watt, F.M.; Estrach, S.; Ambler, C.A. Epidermal Notch signaling: Differentiation, cancer and adhesion. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2008, 20, 171–179.

- Gridley, T. Notch signaling in the vasculature. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2010, 92, 277–309.

- Lim, C.H.; Sun, Q.; Ratti, K.; Lee, S.H.; Zheng, Y.; Takeo, M.; Lee, W.; Rabbani, P.; Plikus, M.V.; Cain, J.E.; et al. Hedgehog stimulates hair follicle neogenesis by creating inductive dermis during murine skin wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4903.

- Chen, L.; Tredget, E.E.; Wu, P.Y. Paracrine factors of mesenchymal stem cells recruit macrophages and endothelial lineage cells and enhance wound healing. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1886.

- Cao, Y.; Gang, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, G. Mesenchymal stem cells improve healing of diabetic foot ulcer. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 9328347.