The yeast distributes ubiquitously in nature with clearly structured populations. The baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has become a powerful model in ecology and evolutionary biology. The global genetic diversity of S. cerevisiae is mainly contributed by strains from Far East Asia, and the ancient basal lineages of the species have been found only in China, supporting an ‘out-of-China’ origin hypothesis. The wild and domesticated populations are clearly separated in phylogeny and exhibit hallmark differences in sexuality, heterozygosity, gene copy number variation (CNV), horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and introgression events, and maltose utilization ability. The domesticated strains from different niches generally form distinct lineages and harbor lineage-specific CNVs, HGTs and introgressions, which contribute to their adaptations to specific fermentation environments.

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- ecology

- evolution

- population genomics

1. Introduction

2. The Life Cycle of S. cerevisiae

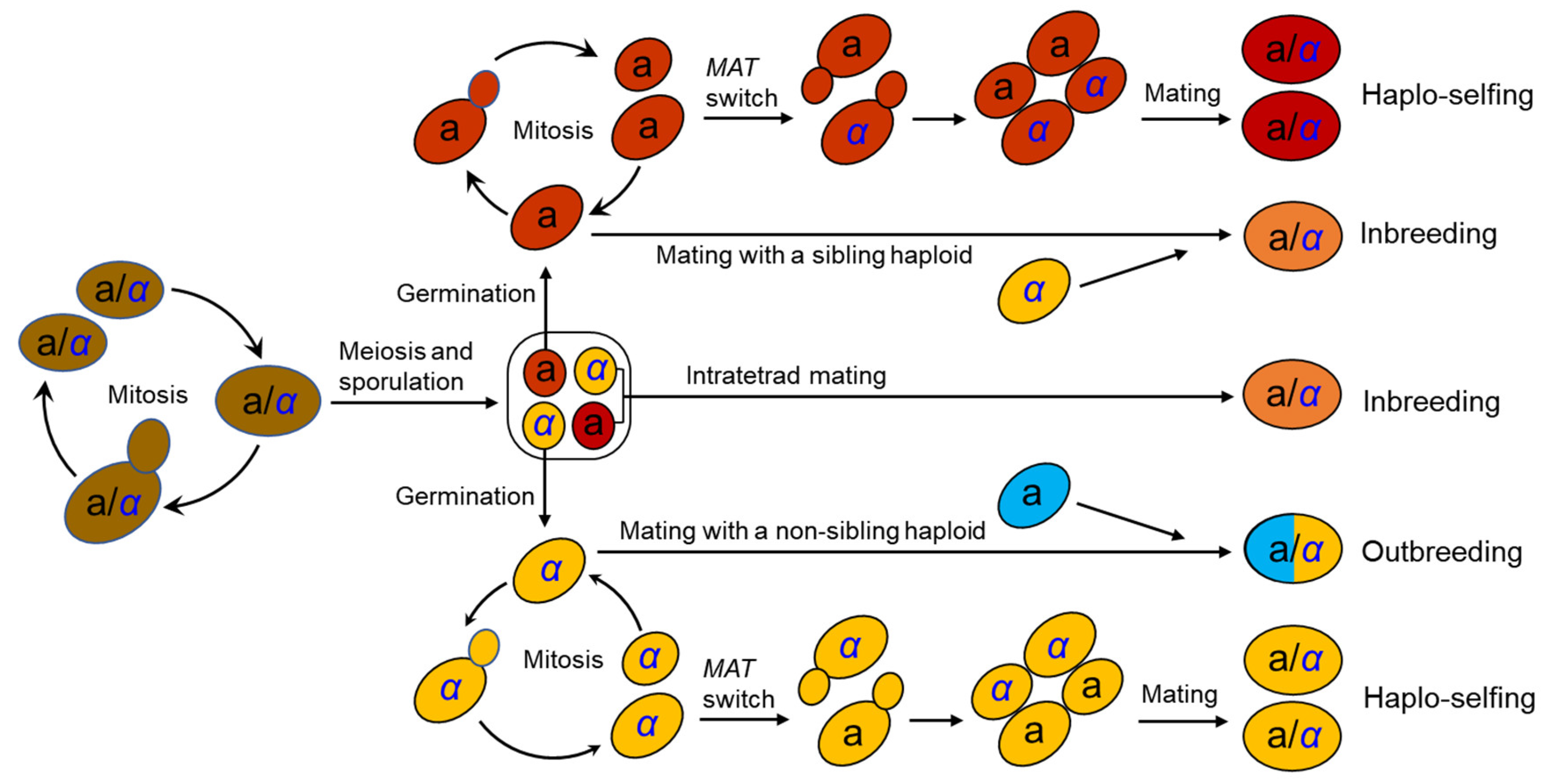

The life cycle of S. cerevisiae has been well documented in the laboratory [15] (Figure 1). S. cerevisiae usually grows as a diploid in artificial nutrient-rich medium such as YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose) and reproduces clonally by budding, with an optimal growth temperature of around 30°C. It will sporulate and undergo meiosis in response to nitrogen starvation, resulting in the formation of four haploid spores in an ascus. Two of the spores have mating type a (MATa) and the other two MATα. Mating type is determined by a single locus MAT in the middle of the right arm of chromosome III [16][17]. A pair of spores with opposite mating types can mate within the ascus upon germination (intratetrad mating or automixis) and form a diploid cell. Ascospores can also germinate to form haploid cells, which can reproduce mitotically by budding, resulting in the formation of MATa and MATα haploid clones. However, the haploid phase usually only exists for a very short period in the life cycle. A haploid cell can mate with another haploid with an opposite mating type either from a different ascus of the same strain (selfing) or from a different strain (outcrossing or amphimixis). Haploid cells can also undergo a mating-type switch by exchanging types at the MAT locus via a gene conversion event (Figure 1). The molecular mechanism of mating-type switching is the replacement of the genetic factor of the MAT locus by a copy of the alternative factor located at a silent locus.

3. Habitats of S. cerevisiae in the Wild

4. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of S. cerevisiae

The approximately 9000 year domestication history of yeast [33] is similar to that of key plants and animals, which usually have a domestication history of around 10,000 years [34]. The domestication of plants and animals has been extensively studied since Darwin [34][35], however, research centering on the domestication of yeast has rarely been performed until recently. The lag was partially due to the lack of reference wild populations of S. cerevisiae and poor understanding about the natural history of the yeast. The phylogenetic distinction between wild and domesticated populations of S. cerevisiae was shown for the first time in 2005 [36] based on sequence analysis of five genes (CCA1, CYT1, MLS1, PDR10, and ZDS2) and their promoters in 81 strains. The S. cerevisiae strains employed in the early studies of population genetics and genomics were mainly from fermentation and human-associated environments, and wild strains were poorly represented. The wild strains designated in these studies were mainly from vineyards, oak tree bark and associated soil. Though the oak strains were considered “truly wild” in these studies, the association of the oak strains with human activities cannot be excluded, because the oak trees sampled were usually located in man-made environments or environments frequently visited by humans, such as parks or arboreta [10][37].5. Origin of the Domesticated Population of S. cerevisiae

Previous studies generally support the China/Far East Asia origin hypothesis of S. cerevisiae. Ancient basal lineages of S. cerevisiae have not been found outside China, despite extensive survey in Europe [38][39], North America [10][40], South America (including Amazonian rainforests) [41], New Zealand [42][43][44] and Africa [13][45][46]. However, the origin of the domesticated population of S. cerevisiae is still a debated issue [47]. Basically, two hypotheses have been proposed: (1) Chinese or Asian wild S. cerevisiae strains immigrated to other regions and were then domesticated independently in different areas [48][49]; or (2) after a single ancestral domestication event occurring most likely in China or Asia, domesticated ancestors were later introduced to other regions [12][13]. A population genomics study mainly on ale beer and wine yeasts showed that present industrial yeasts originated from only a limited number of ancestors [50], but the ancestors were not specified. Other studies [48][49] revealed close relationships of different domesticated lineages with different wild relatives of S. cerevisiae, suggesting that multiple independent domestication events led to the origin of various domesticated lineages. This multiple domestication events scenario was also supported by additional studies based on different strain and data sets [36][51][44][52][53]. However, the closest local wild relatives of individual domesticated lineages have not been specified, except for the wine lineage.6. Intrinsically Different Life Strategies of the Wild and Domesticated Populations of S. cerevisiae

Previous studies have shown that S. cerevisiae occurs in both natural and man-made environments with high genetic diversity and clear population structure. However, different studies resulted in different answers to a fundamental question of whether the diversity of S. cerevisiae is primarily driven by niche adaptation and selection, or neutral genetic drift, echoing the long standing selectionist vs. neutralist debate in evolutionary biology. Some studies show that S. cerevisiae strains are principally organized by geography, highlighting the role of genetic drift in shaping the population structure of S. cerevisiae [48][40][44][53], while others recognize mainly ecologically defined populations, suggesting that natural selection may play a more important role than geographic factors in the diversification of S. cerevisiae [36][37][54][55][56]. Recent studies suggest that the forces driving the evolution of S. cerevisiae are more complicated, and neither geographic nor ecologic factors can fully explain the population structure of the species. Different levels of divergence and different lineages may have resulted from different driving forces. In general, ecology seems to be the primary force driving the evolution of S. cerevisiae, since the wild and domesticated populations are distinct phylogenetically and the domesticated population is apparently an outcome of natural and artificial selection for adaptation to nutrient- or sugar-rich environments [12][13][36]. Extensive adaptive genome variations, including different patterns in heterozygosity, SNPs, gene contents and copy numbers, and allele distributions have been observed between wild and domesticated populations [12][13][49], suggesting that wild and domesticated populations have evolved different life strategies for adaptation to generally different environments.7. The Diversity of the Domesticated S. cerevisiae Is Primarily Driven by Ecology

Ecology apparently plays a main role in the divergence of the domesticated lineages of S. cerevisiae. Osmolarity seems to be the primary selection pressure, since strains associated with liquid- and solid-state fermentation are clearly separated [12][13]. The main difference between the two types of fermentation is the water content of the substrates. The water contents are usually 80–90% and 40–60% in the liquid- and solid-state fermentation, respectively [13]. Within each of the LSF and SSF groups, strains associated with different food and beverage fermentation usually form distinct lineages. Remarkably, strains for the fermentation of grape juice, wort, milk, agave juice and honey, cluster in the Wine, Beer, Milk/Cheese, Mexican Agave and African Honey Wine lineages in the LSF group, respectively; while strains for the fermentation of dough, sorghum grain, barley grain, and cooked rice form the Mantou, Baijiu, Qingkejiu, and Huangjiu/Sake lineages in the SSF groups, respectively, regardless of their geographic origins (Figure 4) [12][13][49][57]. Extensive genetic variations leading to consequent phenotypic trait changes for adaptation to specific niches have been identified in different domesticated lineages [12][13][58][59][60]. Three unique HGT fragments (regions A–C) from Zygosaccharomyces bailii were identified from wine yeast strains [61]. These regions harbor key functional genes in wine fermentation and thus are believed to contribute to the adaptation of wine yeast strains to grape juice fermentation. Genes in these regions have also been found from other lineages, but are mostly limited in the LSF group [12][13].8. The Diversification of the Wild S. cerevisiae Is Largely Consistent with a Neutral Model

The genetic diversity of the whole species S. cerevisiae is mainly contributed by its wild population, which is clearly structured with highly diverged lineages [11][12][13][14]. Broadly, geography seems to play a main role in the diversification of the wild strains. Strains from forests in different countries or regions usually form different lineages, such as the North American Oak, Far East Russia, Ecuador, and Malaysian lineages [13][49]. The S. cerevisiae strains from Amazon forests in Brazil also formed different lineages [41]. Within China, the primeval forest strains from south China are generally not mixed with those from north China [11][12][13]. The forest strains from different regions (Shaanxi and Beijing) in north China also form different lineages (CHN-II and CHN-IV, respectively). However, the role of ecological factors cannot be excluded because different countries and regions may be ecologically different. The flora in tropical and subtropical forests in southern China are different from those in the temperate forests in northern China [62]. Conversely, the high genetic diversities of wild strains from single locations have been well documented. Primeval forest strains from a single location may belong to highly diverged lineages, exhibiting a sympatric differentiation phenomenon [11][12][13].9. A Modified Genome Renewal Hypothesis for Explaining the Diversification of S. Cerevisiae in the Wild

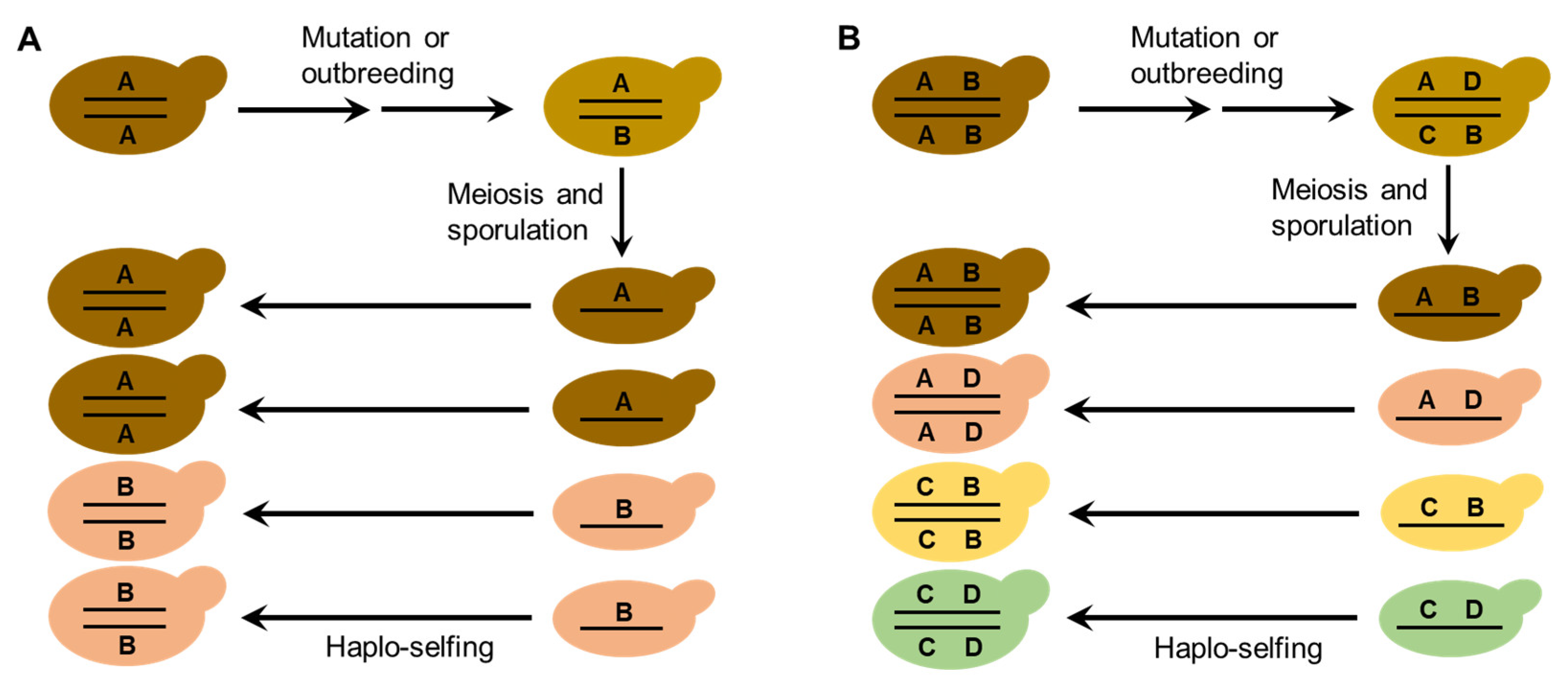

The life cycle and mating behaviors of S. cerevisiae (Figure 1) probably contribute to the reproductive isolation and diversification of wild strains. Efficient sporulation might be a selected trait for S. cerevisiae to survive in the wild [21]. Repetitive starvation and aridity pressures in the wild would select for the capability to return efficiently to a diploid state, which is necessary for sporulation. Autodiploidization mediated by mating-type switch and intratetrad mating would apparently provide a selective advantage because these processes avoid the risk of the absence of adjacent mates with opposite mating types [18][21]. Multiple reinventions of mating-type switching have occurred during the evolution of budding yeasts, suggesting strong natural selection in favor of this property [19]. The seemly obligate homothallism of the wild S. cerevisiae probably prevents outbreeding and genetic admixture. On the other hand, mutation or occasional outbreeding due to population admixture of the wild S. cerevisiae caused by human or animal (insect) activities could create heterozygous strains. Reinstatement to a homozygous state of heterozygous strains due to haplo-selfing would produce new genotypes as predicted by Mortimer’s genome renewal hypothesis [63][27][64]. In the case of wild strain diversification, the hypothesis needs to be modified, because purging of deleterious alleles is not a necessary function of this model. The neutral polymorphisms due to mutation or outbreeding in the occasionally formed heterozygous strains in nature can be fixed via subsequent haplo-selfing, as illustrated in Figure 2. The modified genome renewal model can explain sympatric diversification observed in wild S. cerevisiae, for neither geographic nor ecological isolation is required in this model.

References

- Dedeken, R.H. The crabtree effect: A regulatory system in yeast. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1966, 44, 149–156.

- Piskur, J.; Rozpedowska, E.; Polakova, S.; Merico, A.; Compagno, C. How did Saccharomyces evolve to become a good brewer? Trends Genet. 2006, 22, 183–186.

- Goffeau, A.; Barrell, B.G.; Bussey, H.; Davis, R.W.; Dujon, B.; Feldmann, H.; Galibert, F.; Hoheisel, J.D.; Jacq, C.; Johnston, M.; et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science 1996, 274, 546–567.

- Giaever, G.; Chu, A.M.; Ni, L.; Connelly, C.; Riles, L.; Veronneau, S.; Dow, S.; Lucau-Danila, A.; Anderson, K.; Andre, B.; et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 2002, 418, 387–391.

- Richardson, S.M.; Mitchell, L.A.; Stracquadanio, G.; Yang, K.; Dymond, J.S.; DiCarlo, J.E.; Lee, D.; Huang, C.L.V.; Chandrasegaran, S.; Cai, Y.Z.; et al. Design of a synthetic yeast genome. Science 2017, 355, 1040–1044.

- Shao, Y.Y.; Lu, N.; Wu, Z.F.; Cai, C.; Wang, S.S.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhou, F.; Xiao, S.J.; Liu, L.; Zeng, X.F.; et al. Creating a functional single-chromosome yeast. Nature 2018, 560, 331–335.

- Engel, S.R.; Dietrich, F.S.; Fisk, D.G.; Binkley, G.; Balakrishnan, R.; Costanzo, M.C.; Dwight, S.S.; Hitz, B.C.; Karra, K.; Nash, R.S.; et al. The reference genome sequence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Then and now. G3 2014, 4, 389–398.

- Warringer, J.; Zorgo, E.; Cubillos, F.A.; Zia, A.; Gjuvsland, A.; Simpson, J.T.; Forsmark, A.; Durbin, R.; Omholt, S.W.; Louis, E.J.; et al. Trait variation in yeast Is defined by population history. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002111.

- Replansky, T.; Koufopanou, V.; Greig, D.; Bell, G. Saccharomyces sensu stricto as a model system for evolution and ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 494–501.

- Sniegowski, P.D.; Dombrowski, P.G.; Fingerman, E. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces paradoxus coexist in a natural woodland site in North America and display different levels of reproductive isolation from European conspecifics. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002, 1, 299–306.

- Wang, Q.M.; Liu, W.Q.; Liti, G.; Wang, S.A.; Bai, F.Y. Surprisingly diverged populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in natural environments remote from human activity. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 5404–5417.

- Duan, S.F.; Han, P.J.; Wang, Q.M.; Liu, W.Q.; Shi, J.Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, X.L.; Bai, F.Y. The origin and adaptive evolution of domesticated populations of yeast from Far East Asia. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2690.

- Han, D.Y.; Han, P.J.; Rumbold, K.; Koricha, A.D.; Duan, S.F.; Song, L.; Shi, J.Y.; Li, K.; Wang, Q.M.; Bai, F.Y. Adaptive gene content and allele distribution variations in the wild and domesticated populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 247.

- Liti, G. The fascinating and secret wild life of the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. Elife 2015, 4, e05835.

- Herskowitz, I. Life cycle of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1988, 52, 536–553.

- Haber, J.E. Mating-type genes and MAT switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2012, 191, 33–64.

- Lee, C.S.; Haber, J.E. Mating-type gene switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiolol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 491–514.

- Hanson, S.J.; Wolfe, K.H. An evolutionary perspective on yeast mating-type switching. Genetics 2017, 206, 9–32.

- Krassowski, T.; Kominek, J.; Shen, X.X.; Opulente, D.A.; Zhou, X.F.; Rokas, A.; Hittinger, C.T.; Wolfe, K.H. Multiple reinventions of mating-type switching during budding yeast evolution. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 2555–2562.

- Zakharov, I.A. Intratetrad mating and its genetic and evolutionary consequences. Russ. J. Genet. 2005, 41, 402–411.

- Knop, M. Evolution of the hemiascomyclete yeasts: On life styles and the importance of inbreeding. Bioessays 2006, 28, 696–708.

- Martini, A. Origin and domestication of the wine yeast. J. Wine Res. 1993, 4, 165–176.

- Vaughanmartini, A.; Martini, A. Facts, myths and legends of the prime industrial microoganism. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1995, 14, 514–522.

- Naumov, G.I. Genetic identification of biological species in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1996, 17, 295–302.

- Camperio-Ciani, A.; Corna, F.; Capiluppi, C. Evidence for maternally inherited factors favouring male homosexuality and promoting female fecundity. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. Ser. B 2004, 271, 2217–2221.

- Banno, I.; Mikata, K. Ascomycetous yeasts isolated from forest materials in Japan. IFO Res. Commun. 1981, 10, 10–19.

- Mortimer, R.K. Evolution and variation of the yeast (Saccharomyces) genome. Genome Res. 2000, 10, 403–406.

- Naumov, G.I.; Naumova, E.S. Detection of a wild population of yeast of the biological species Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Siberia. Mikrobiologiia 1991, 60, 537–540.

- Naumov, G.I.; Naumova, E.S.; Sniegowski, P.D. Saccharomyces paradoxus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are associated with exudates of North American oaks. Can. J. Microbiol. 1998, 44, 1045–1050.

- Torok, T.; Mortimer, R.K.; Romano, P.; Suzzi, G.; Polsinelli, M. Quest for wine yeasts-an old story revisited. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1996, 17, 303–313.

- Mortimer, R.; Polsinelli, M. On the origins of wine yeast. Res. Microbiol. 1999, 150, 199–204.

- Redzepovic, S.; Orlic, S.; Sikora, S.; Majdak, A.; Pretorius, I.S. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces paradoxus strains isolated from Croatian vineyards. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 35, 305–310.

- McGovern, P.E.; Zhang, J.H.; Tang, J.G.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Hall, G.R.; Moreau, R.A.; Nunez, A.; Butrym, E.D.; Richards, M.P.; Wang, C.S.; et al. Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17593–17598.

- Larson, G.; Piperno, D.R.; Allaby, R.G.; Purugganan, M.D.; Andersson, L.; Arroyo-Kalin, M.; Barton, L.; Vigueira, C.C.; Denham, T.; Dobney, K.; et al. Current perspectives and the future of domestication studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6139–6146.

- Darwin, C. The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, 1st ed.; John Murray: London, UK, 1868.

- Fay, J.C.; Benavides, J.A. Evidence for domesticated and wild populations of Sacchoromyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 2005, 1, e5.

- Aa, E.; Townsend, J.P.; Adams, R.I.; Nielsen, K.M.; Taylor, J.W. Population structure and gene evolution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 702–715.

- Sampaio, J.P.; Goncalves, P. Natural populations of Saccharomyces kudriavzevii in Portugal are associated with oak bark and are sympatric with S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 2144–2152.

- Almeida, P.; Barbosa, R.; Zalar, P.; Imanishi, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Turchetti, B.; Legras, J.L.; Serra, M.; Dequin, S.; Couloux, A.; et al. A population genomics insight into the Mediterranean origins of wine yeast domestication. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 5412–5427.

- Cromie, G.A.; Hyma, K.E.; Ludlow, C.L.; Garmendia-Torres, C.; Gilbert, T.L.; May, P.; Huang, A.A.; Dudley, A.M.; Fay, J.C. Genomic sequence diversity and population structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae assessed by RAD-seq. G3 2013, 3, 2163–2171.

- Barbosa, R.; Almeida, P.; Safar, S.V.B.; Santos, R.O.; Morais, P.B.; Nielly-Thibault, L.; Leducq, J.B.; Landry, C.R.; Goncalves, P.; Rosa, C.A.; et al. Evidence of natural hybridization in Brazilian wild lineages of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 317–329.

- Knight, S.; Goddard, M.R. Quantifying separation and similarity in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae metapopulation. ISME J. 2015, 9, 361–370.

- Gayevskiy, V.; Lee, S.; Goddard, M.R. European derived Saccharomyces cerevisiae colonisation of New Zealand vineyards aided by humans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fow091.

- Goddard, M.R.; Anfang, N.; Tang, R.Y.; Gardner, R.C.; Jun, C. A distinct population of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in New Zealand: Evidence for local dispersal by insects and human-aided global dispersal in oak barrels. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 63–73.

- Tapsoba, F.; Legras, J.L.; Savadogo, A.; Dequin, S.; Traore, A.S. Diversity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains isolated from Borassus akeassii palm wines from Burkina Faso in comparison to other African beverages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 211, 128–133.

- Ludlow, C.L.; Cromie, G.A.; Garmendia-Torres, C.; Sirr, A.; Hays, M.; Field, C.; Jeffery, E.W.; Fay, J.C.; Dudley, A.M. Independent origins of yeast associated with coffee and cacao fermentation. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 965–971.

- Steensels, J.; Gallone, B.; Voordeckers, K.; Verstrepen, K.J. Domestication of industrial microbes. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R381–R393.

- Liti, G.; Carter, D.M.; Moses, A.M.; Warringer, J.; Parts, L.; James, S.A.; Davey, R.P.; Roberts, I.N.; Burt, A.; Koufopanou, V.; et al. Population genomics of domestic and wild yeasts. Nature 2009, 458, 337–341.

- Peter, J.; De Chiara, M.; Friedrich, A.; Yue, J.X.; Pflieger, D.; Bergstrom, A.; Sigwalt, A.; Barre, B.; Freel, K.; Llored, A.; et al. Genome evolution across 1011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates. Nature 2018, 556, 339–344.

- Gallone, B.; Steensels, J.; Prahl, T.; Soriaga, L.; Saels, V.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Merlevede, A.; Roncoroni, M.; Voordeckers, K.; Miraglia, L.; et al. Domestication and divergence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae beer yeasts. Cell 2016, 166, 1397–1410.e16.

- Pontes, A.; Hutzler, M.; Brito, P.H.; Sampaio, J.P. Revisiting the taxonomic synonyms and populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae-phylogeny, phenotypes, ecology and domestication. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 903.

- Legras, J.L.; Merdinoglu, D.; Cornuet, J.M.; Karst, F. Bread, beer and wine: Saccharomyces cerevisiae diversity reflects human history. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 2091–2102.

- Ezeronye, O.U.; Legras, J.L. Genetic analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains isolated from palm wine in eastern Nigeria. Comparison with other African strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 1569–1578.

- Schacherer, J.; Shapiro, J.A.; Ruderfer, D.M.; Kruglyak, L. Comprehensive polymorphism survey elucidates population structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 2009, 458, 342–345.

- Versavaud, A.; Courcoux, P.; Roulland, C.; Dulac, L.; Hallet, J.N. Genetic diversity and geographical-distribution of wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains from the wine-producing area of Charentes, France. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 3521–3529.

- Ezov, T.K.; Boger-Nadjar, E.; Frenkel, Z.; Katsperovski, I.; Kemeny, S.; Nevo, E.; Korol, A.; Kashi, Y. Molecular-genetic biodiversity in a natural population of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae from “Evolution canyon”: Microsatellite polymorphism, ploidy and controversial sexual status. Genetics 2006, 174, 1455–1468.

- Legras, J.L.; Galeote, V.; Bigey, F.; Camarasa, C.; Marsit, S.; Nidelet, T.; Sanchez, I.; Couloux, A.; Guy, J.; Franco-Duarte, R.; et al. Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to fermented food environments reveals remarkable genome plasticity and the footprints of domestication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1712–1727.

- Libkind, D.; Peris, D.; Cubillos, F.A.; Steenwyk, J.L.; Opulente, D.A.; Langdon, Q.K.; Rokas, A.; Hittinger, C.T. Into the wild: New yeast genomes from natural environments and new tools for their analysis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2020, 20, foaa008.

- Gallone, B.; Steensels, J.; Mertens, S.; Dzialo, M.C.; Gordon, J.L.; Wauters, R.; Thesseling, F.A.; Bellinazzo, F.; Saels, V.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; et al. Interspecific hybridization facilitates niche adaptation in beer yeast. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1562–1575.

- Goncalves, M.; Pontes, A.; Almeida, P.; Barbosa, R.; Serra, M.; Libkind, D.; Hutzler, M.; Goncalves, P.; Sampaio, J.P. Distinct domestication trajectories in top-fermenting beer yeasts and wine yeasts. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2750–2761.

- Novo, M.; Bigey, F.; Beyne, E.; Galeote, V.; Gavory, F.; Mallet, S.; Cambon, B.; Legras, J.L.; Wincker, P.; Casaregola, S.; et al. Eukaryote-to-eukaryote gene transfer events revealed by the genome sequence of the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae EC1118. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16333–16338.

- Lu, L.M.; Mao, L.F.; Yang, T.; Ye, J.F.; Liu, B.; Li, H.L.; Sun, M.; Miller, J.T.; Mathews, S.; Hu, H.H.; et al. Evolutionary history of the angiosperm flora of China. Nature 2018, 554, 234–258.

- Mortimer, R.K.; Romano, P.; Suzzi, G.; Polsinelli, M. Genome renewal: A new phenomenon revealed from a genetic study of 43 strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae derived from natural fermentation of grape musts. Yeast 1994, 10, 1543–1552.

- Magwene, P.M. Revisiting mortimer’s genome renewal hypothesis: Heterozygosity, homothallism, and the potential for adaptation in yeast. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 781, 37–48.