You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Yvaine Wei and Version 2 by Yvaine Wei.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder associated with hyperandrogenemia and failure of ovulation, which is often accompanied by metabolic abnormalities, including obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance. Research on proteins and peptides that play roles in metabolic regulation, which may be considered potential insulin resistance markers in some medical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, obesity and PCOS.

- polycystic ovarian syndrome

- insulin resistance

- preptin

- myonectin

- gremlin

- omentin

- nesfatin

1. Introduction

To date, most research has been devoted to factors deriving directly from the white adipose tissue (WAT)—also known as adipokines—including adiponectin, resistin, leptin, visfatin, apelin, retinol-binding protein 4, and chemerin, to name but a few [1][2][3][4][5]. It has been shown that adipose tissue may function as an endocrine organ and that it secretes several adipokines, thus constituting a link between body mass excess and glucose level disturbances [3][6]. Adipokines may be synthesized in excess, or their expression may be diminished, in several conditions associated with insulin resistance, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), or polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) [1][4].

PCOS is a frequent endocrine disorder associated with hyperinsulinemia and hyperandrogenemia, which is often accompanied by infertility and obesity [7]. Affected individuals are at increased risk of developing cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, as well as anxiety disorders [8].

The condition is most commonly diagnosed according to the Rotterdam criteria, when two out of the three following features occur (after the exclusion of related disorders): oligo/anovulation, clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism, or polycystic ovaries on ultrasound [9][10].

The prevalence of PCOS has been estimated as 4–26% depending on the studied population (in terms of age, ethnicity, and so on) and applied criteria. It has been shown that adoption of the NIH/NICD guidelines may account for recognition of PCOS in 4–8% adult female patients, while this rate may be as high as 15–20%, when ESHRE recommendations are acknowledged [8].

Over the years, many hypotheses have been introduced, including genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors [11]. The key pathogenetic factors include hyperandrogenemia, subclinical inflammation, and defective insulin signaling [12]. It has been evidenced that up to 50–80% of women with PCOS are diagnosed with insulin resistance [6][8][13]. Hyperinsulinemia is responsible for metabolic and cardiovascular complications [14], as well as decreasing sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) production in the liver (resulting in an increase of free and bioactive androgen levels in the circulation) and potentiating the luteinizing hormone (LH)-dependent effect on the ovarian cells, leading to the enhanced synthesis of androgens [1]. Hyperandrogenemia in females further aggravates the course of metabolic complications [15][16].

Moreover, it has been shown that the presence of some bacterial species may lead to altered secretion of several peptides involved in the metabolic homeostasis and appetite regulation; for example, an increase of Bacteroides species has been shown to be associated with the dysregulation of ghrelin and peptide YY [17].

Last, but not least, in patients with PCOS, many studies assessing the levels of adipokines have been conducted [1] and it has been indicated that the dysregulation of such hormones leads to insulin resistance [2].

At present, there are emerging data regarding peptides/glycoproteins, synthesized in other tissues than WAT, which may also be involved in the pathomechanism of insulin resistance. Some of them have been investigated as potential insulin resistance biomarkers in PCOS [1]. Studying new possible markers may not only provide the insight into the intricate pathomechanism of PCOS, but also implicates that measurement of several target proteins that may provide useful information about the severity of the condition, possible complications, and prognoses, or which may serve as helpful tool for the early detection of metabolic complications. The analysis of such markers may also play a significant role in monitoring of the course of a disease [11].

2. Nesfatin-1

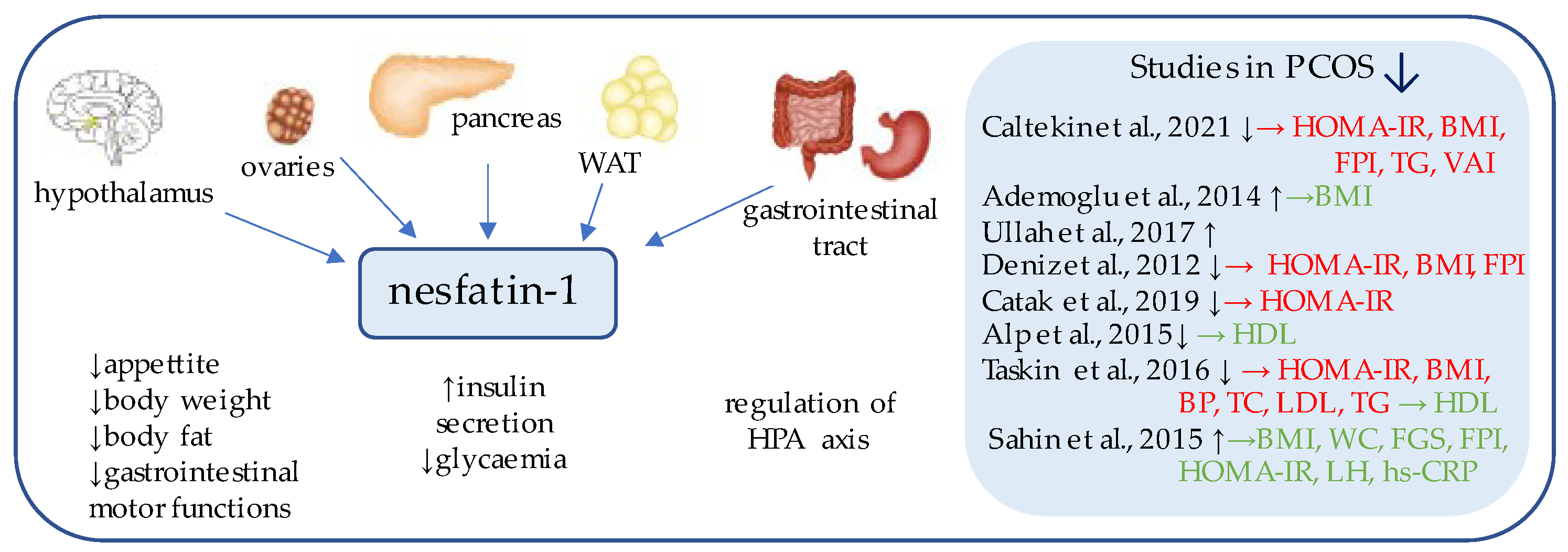

Nesfatin-1 (Figure 1) is an 82-amino acid neuropeptide derived from the post-translational processing of the N-terminal fragment of nucleobindin2 (NUCB2) [18], which was originally identified as an anorexigenic hypothalamic neuropeptide, a chronic intracerebroventricular injection of which reduced the food intake and decreased body weight and the amount of body fat [19]. Its expression has been detected in the areas responsible for appetite regulation, such as the arcuate, paraventricular, and supraoptic nuclei, as well as in the lateral hypothalamic area and zona incerta [19].

Figure 1. Role of nesfatin-1 in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and PCOS. List of the studies assessing serum nesfatin level in the PCOS patients. ↑/↓ indicates whether concentration level of serum nesfatin was increased/decreased in PCOS individuals (p < 0.05); → (green)—indicates positive correlation between serum nesfatin and particular indicators; → (red)—indicates negative correlation between serum nesfatin and particular indicator; HOMA-IR—Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; BMI—body mass index; FPI—fasting plasma insulin; TG—triglycerides; VAI—Visceral Adiposity Index; HDL—high density lipoprotein; BP—blood pressure; TC—total cholesterol; LDL—low-density lipoproteins; WC—waist circumference; FGS—Ferriman–Gallwey Score; LH—Luteinizing Hormone; hs-CRP—high-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; WAT—white adipose tissue; HPA axis—Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal axis.

Subsequent studies have focused on the peripheral expression of nesfatin and proved its synthesis on mRNA and protein levels within the gut, pancreas, and white adipose tissue [19][20].

Interestingly, in the gastrointestinal tract, nesfatin-1 has been shown to be co-expressed in about 86% of x/A cells with the commonly known appetite-regulator ghrelin, and to a lesser extent, within the D cells with somatostatin and histamine-synthesizing enzyme histidine decarboxylase (HDC) [21][22]. Moreover, in the pancreas of rodents, beta cells co-localize insulin and pronesfatin immunoreactivity [23].

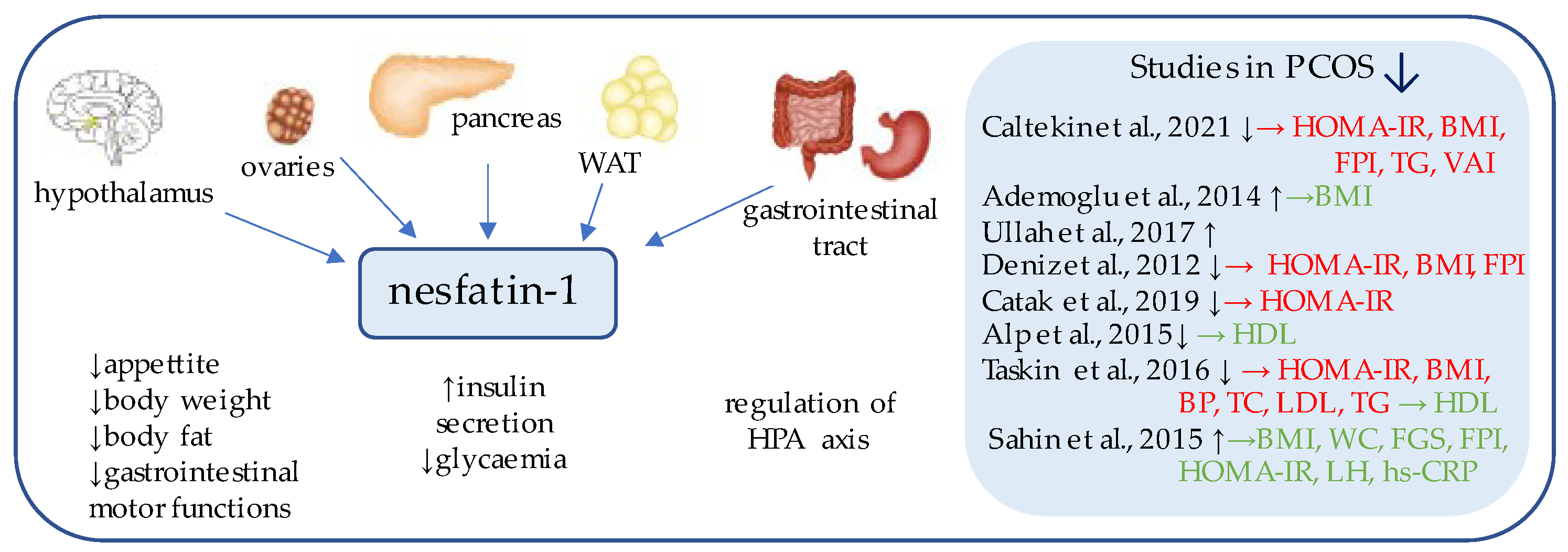

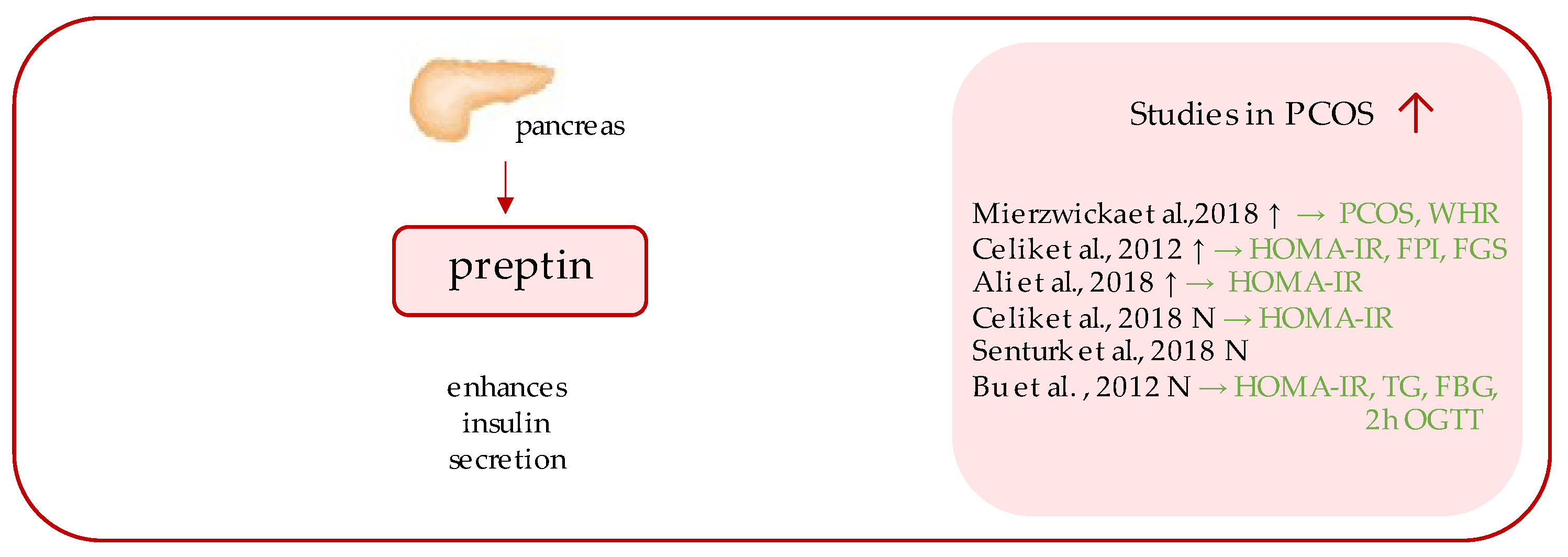

Over the years, several studies aimed at measuring fasting preptin serum concentrations in females with PCOS were undertaken; however, the results of which remain inconsistent, as significantly higher serum preptin concentrations have been detected in some studies [27][28][29], while other studies have undermined this relationship [30][31][32].

Over the years, several studies aimed at measuring fasting preptin serum concentrations in females with PCOS were undertaken; however, the results of which remain inconsistent, as significantly higher serum preptin concentrations have been detected in some studies [27][28][29], while other studies have undermined this relationship [30][31][32].

43. Preptin

Preptin (Figure 2) is a 34-amino acid peptide, a product of the same gene that encodes Insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF II); more precisely, it corresponds to the Asp69–Leu102 sequence of the E-domain of its precursor, proinsulin-like growth factor II [24][25]. The peptide originated from the study of Buchanan et al., who purified it from secretory granules of cultured murine bTC6-F7 pancreatic b-cells [24], where preptin is co-secreted all together with insulin, amylin, and pancreastatin, and exhibits biological function as a glucose-mediated insulin secretion enhancer [26].

Figure 2. Role of preptin in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and PCOS. List of the studies assessing serum nesfatin level in the PCOS patients. ↑/N indicates whether concentration level of serum preptin was increased/unchanged in PCOS individuals (p < 0.05); → (green)—indicates positive correlation between serum nesfatin and particular indicators; PCOS—polycystic ovarian syndrome; WHR—waist-to-hip ratio; HOMA-IR—Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; FPI—fasting plasma insulin; FGS—Ferriman–Gallwey score; TG—triglycerides; FBG—fasting blood glucose; OGTT—oral glucose tolerance test.

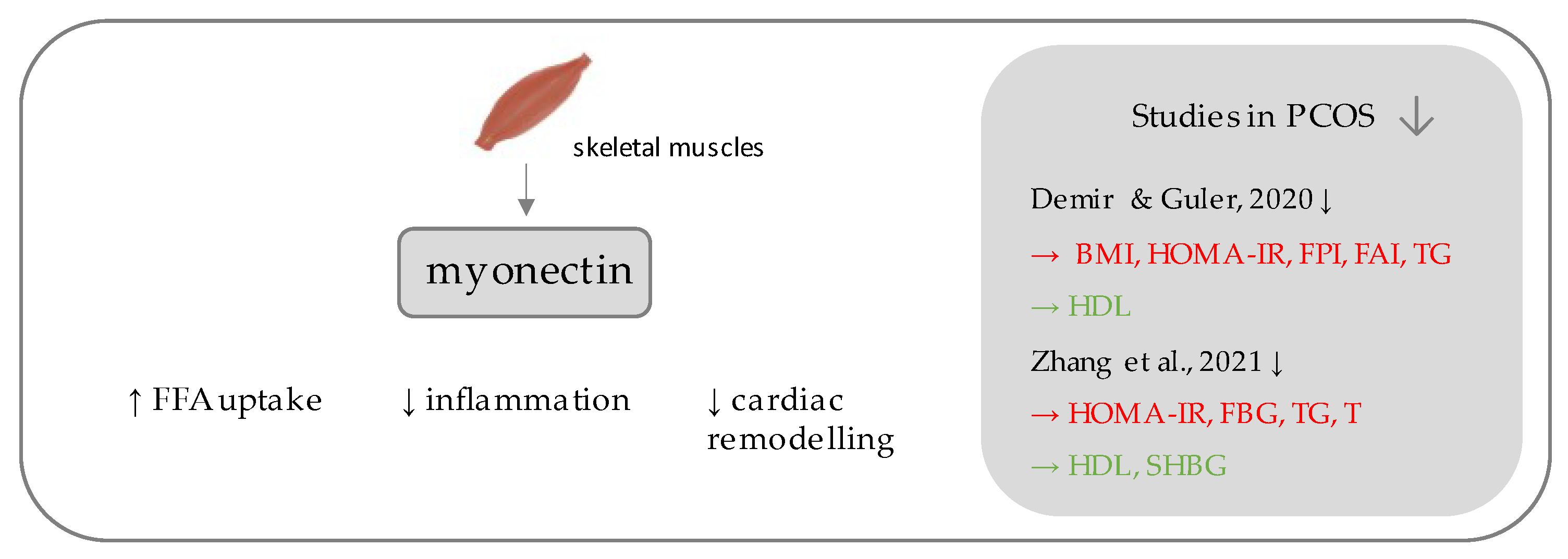

54. Myonectin

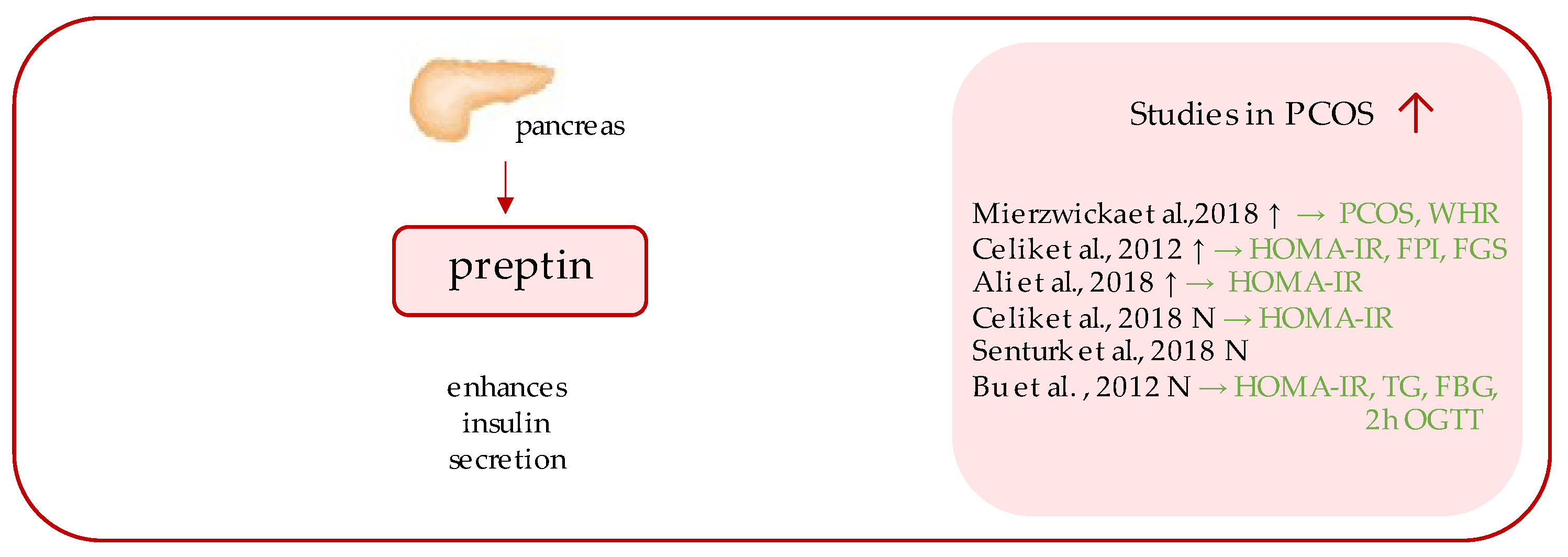

Myonectin (Figure 3) belongs to the C1q/TNF-related proteins (CTRPs), constituting its most recent member, assigned as CTRP-15 [33][34]. CTRPs, due to presence of a C-terminal globular domain, with sequence homology to the immune complement protein C1q are further counted among the C1q protein family [34], together with a commonly known adipokine, adiponectin, which is a well-established insulin-sensitizing hormone [35], the diminished levels of which reflect insulin resistance, which has been repeatedly demonstrated in PCOS individuals [36][37]. Unlike the other CTRPs, which are widely expressed in many tissues, most predominantly in adipocytes [34], myonectin is an example of a myokine, with its highest expression occurring within the skeletal muscles [33]. Initially, its function was linked to the promotion of fatty acid uptake by adipocytes and hepatocytes, consequently leading to a reduction of serum free fatty levels [33]. Importantly, it has been shown to be up-regulated after feeding and physical exercise [33].

Figure 3. Role of myonectin in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and PCOS. List of the studies assessing serum nesfatin level in the PCOS patients. ↓ indicates that concentration level of serum myonectin was decreased in PCOS individuals (p < 0.05); → (green)—indicates positive correlation between serum myonectin and particular indicators; → (red)—indicates negative correlation between serum myonectin and particular indicator; BMI—Body Mass Index; HOMA-IR—Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; FPI—fasting plasma insulin; FAI—free androgen index; TG—triglycerides; HDL—high density lipoproteins; FBG—fasting blood glucose; T—testosterone; SHBG—sex hormone binding globulin.

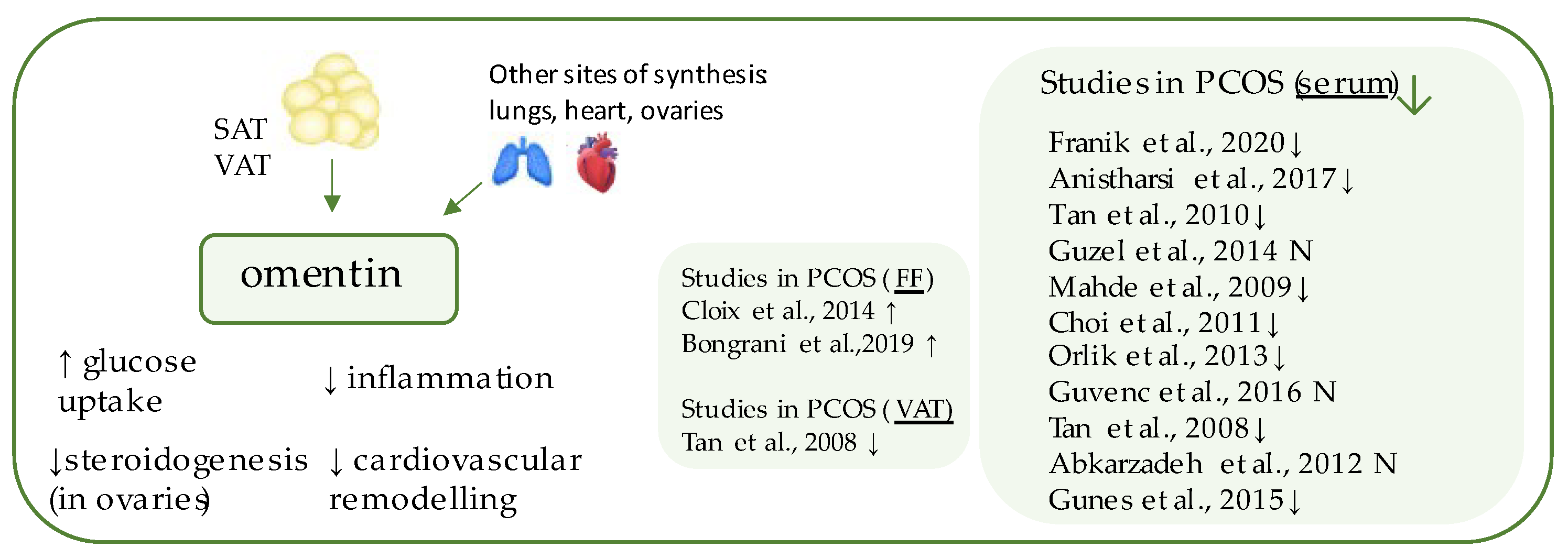

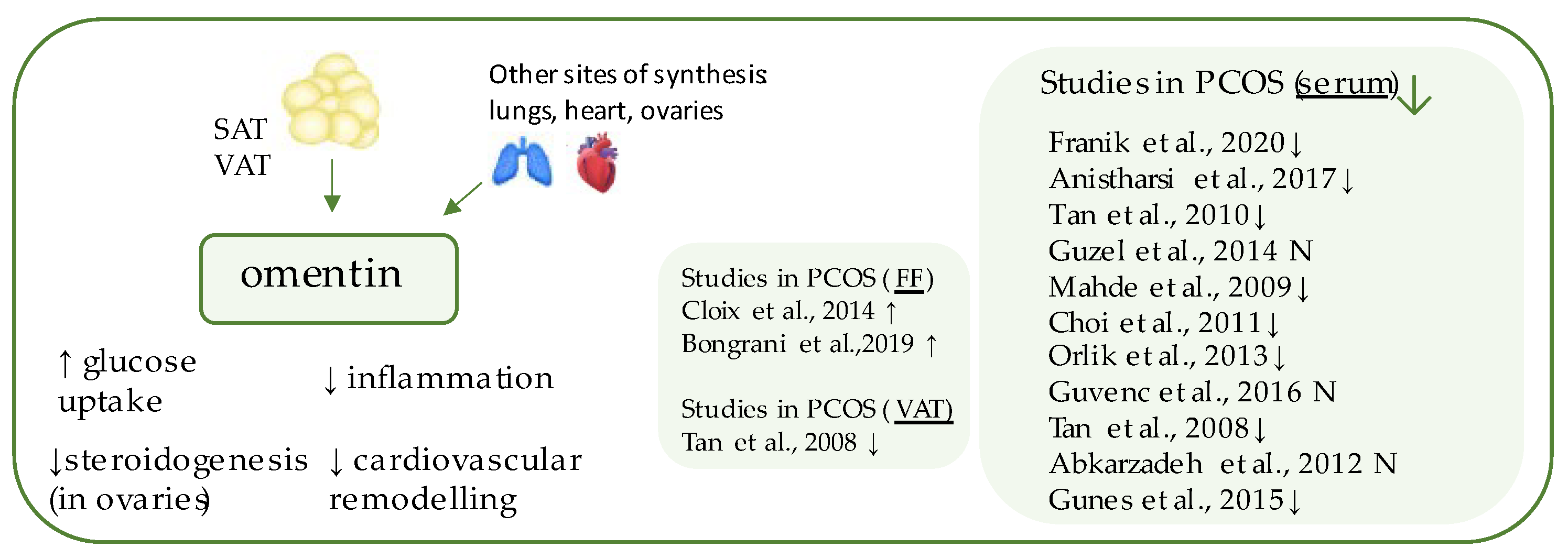

65. Omentin-1

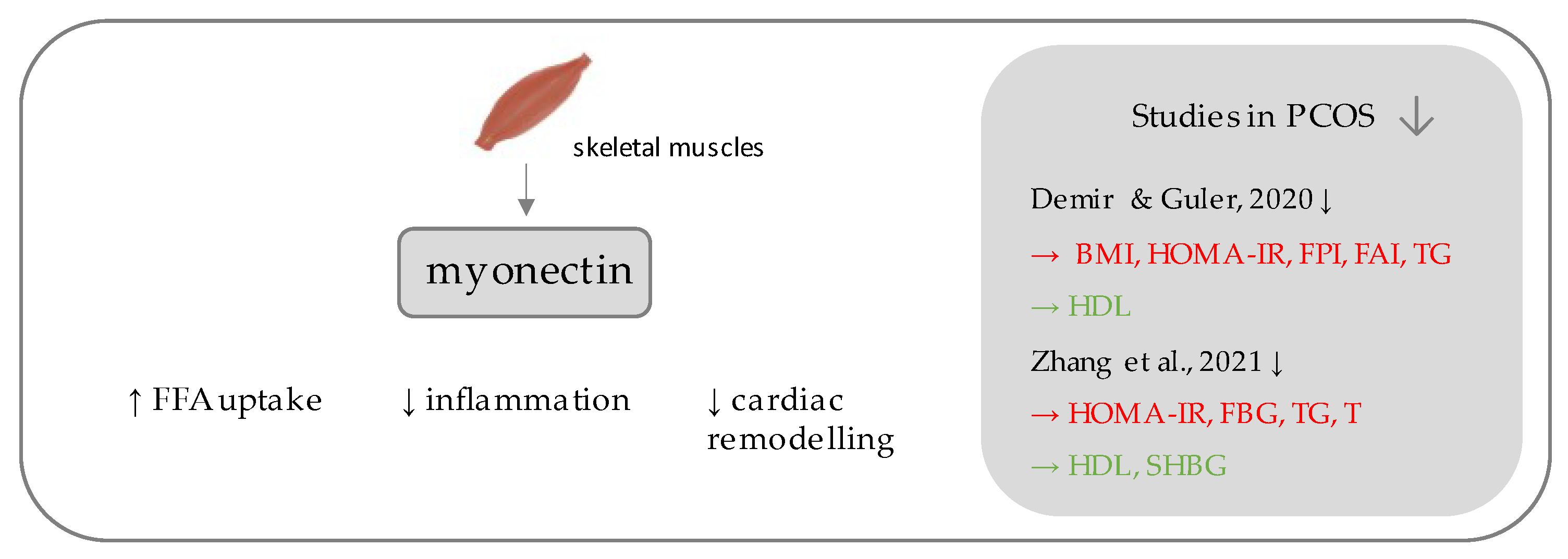

Omentin-1 (Figure 4) is a 296-amino acid glycoprotein, a major form of the circulating omentins in human plasma, products of the gene localized within the 1q22–q23 chromosomal region which has been linked to T2DM in various populations [5][38]. It belongs to the adipokines, the expression of which occurs largely in the visceral (omental) and, to a twenty times lesser extent, in the subcutaneous adipose tissue and is a factor detectable in human serum [39][40]. Indeed, its function relies on increasing insulin-mediated glucose uptake by activating the protein kinase B (PKB or Akt) pathway, and decreased serum concentrations have been detected in individuals with obesity and T2DM [39][41]. It is predominantly positively related to adiponectin and negatively to BMI, leptin, and insulin resistance [41]. Therapies based on body weight reduction have been shown to contribute to elevation of its serum concentration [42][43]. Beside its anti-diabetic properties, omentin also decreases cardiovascular risk and preserves anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic functions, through vasodilation of blood vessels, attenuation of C-reactive protein-induced angiogenesis, and reduction of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-induced inflammation in the endothelium and vascular smooth cells [44][45][46].

Figure 4. Role of omentin in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and PCOS. List of the studies assessing nesfatin level in serum, follicular fluid (FF), and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) of the patients with PCOS. ↓/N indicates that concentration level of omentin was decreased/unchanged in PCOS individuals (p < 0.05).

76. Gremlin

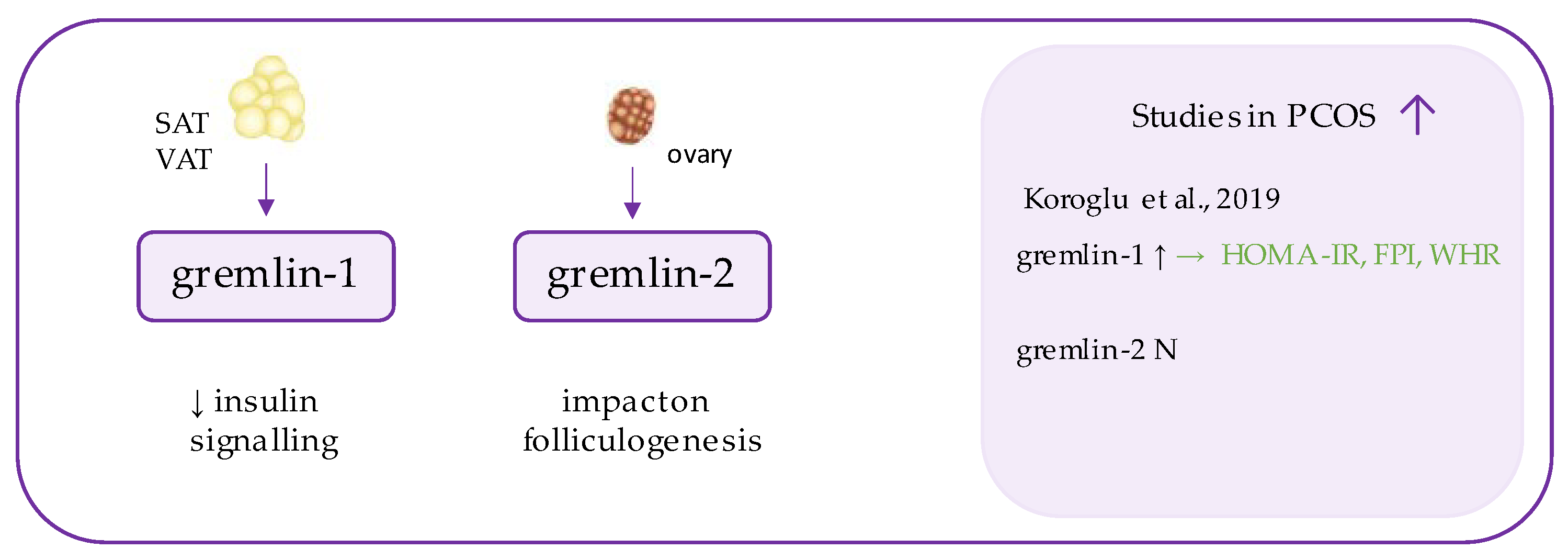

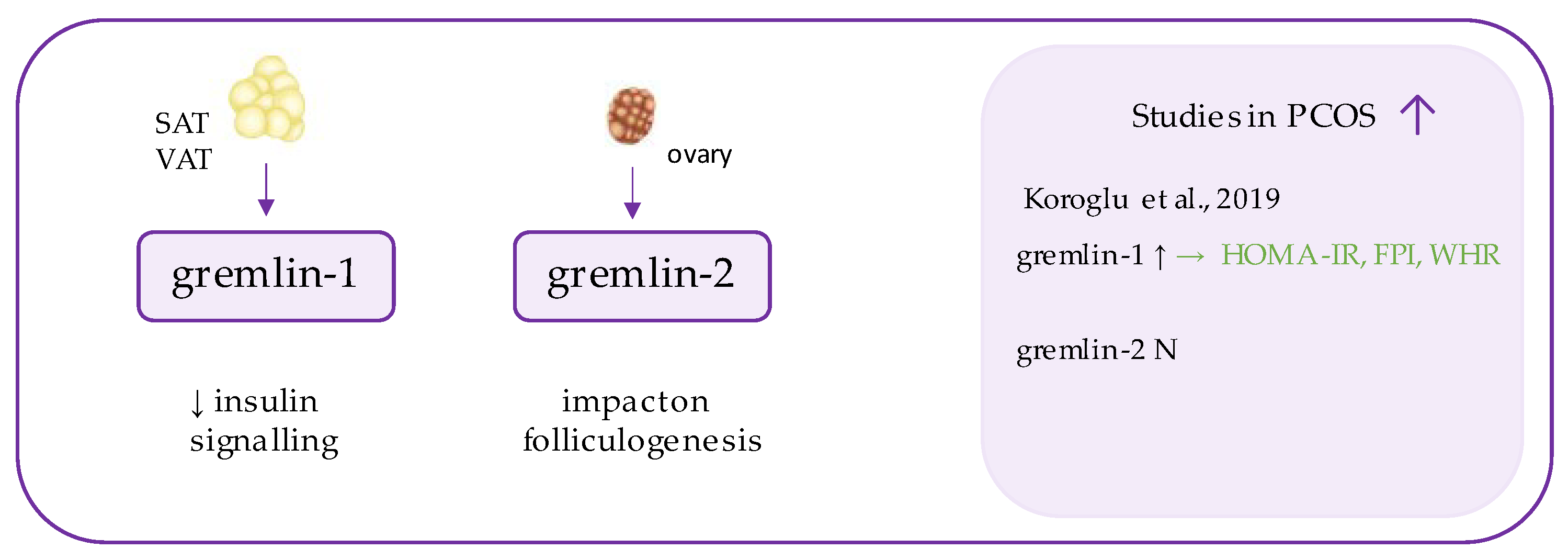

Gremlins (Figure 5) are peptides belonging to DAN family, which function as extracellular antagonists of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), especially BMP2 and BMP4 [47][48]. BMPs are highly conserved proteins, which exhibit transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) activity and regulate cell differentiation during embryogenesis and later stages of life [49]. Gremlins (1 and 2) neutralize those ligands by binding to them and preventing their interaction with receptors and signaling [48].

Figure 5. Role of gremlin in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and PCOS. List of the studies assessing gremlins level in serum of the patients with PCOS. ↑/N indicates whether concentration level of gremlin was increased/unchanged in PCOS individuals (p < 0.05); → (green)—indicates positive correlation between serum omentin and particular indicators; HOMA-IR—Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance, FPI—fasting plasma insulin, WHR—waist-to-hip ratio.

References

- Polak, K.; Czyzyk, A.; Simoncini, T.; Meczekalski, B. New markers of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2017, 40, 1–8.

- Rabe, K.; Lehrke, M.; Parhofer, K.G.; Broedl, U.C. Adipokines and Insulin Resistance. Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 741–751.

- Zorena, K.; Jachimowicz-Duda, O.; Ślęzak, D.; Robakowska, M.; Mrugacz, M. Adipokines and Obesity. Potential Link to Metabolic Disorders and Chronic Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3570.

- Landecho, M.F.; Tuero, C.; Valentí, V.; Bilbao, I.; De La Higuera, M.; Frühbeck, G. Relevance of Leptin and Other Adipokines in Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Risk. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2664.

- Chen, X.; Jia, X.; Qiao, J.; Guan, Y.; Kang, J. Adipokines in reproductive function: A link between obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 50, R21–R37.

- Ozegowska, K.; Pawelczyk, L. The role of insulin and selected adipocytokines in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)—A literature review. Ginekol. Polska 2015, 86, 300–304.

- De Leo, V.; Musacchio, M.C.; Cappelli, V.; Massaro, M.G.; Morgante, G.; Petraglia, F. Genetic, hormonal and metabolic aspects of PCOS: An update. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2016, 14, 38.

- Sirmans, S.; Pate, K. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 6, 1–13.

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Piltonen, T.; Norman, R.J. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1602–1618.

- The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 81, 19–25.

- Sharif, E. New markers for the detection of polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. J. 2019, 10, 62–65.

- Rosenfield, R.L.; Ehrmann, D.A. The Pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): The Hypothesis of PCOS as Functional Ovarian Hyperandrogenism Revisited. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 467–520.

- Chen, W.; Pang, Y. Metabolic Syndrome and PCOS: Pathogenesis and the Role of Metabolites. Metabolites 2021, 11, 869.

- Ormazabal, V.; Nair, S.; Elfeky, O.; Aguayo, C.; Salomon, C.; Zuñiga, F.A. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 122.

- Ye, W.; Xie, T.; Song, Y.; Zhou, L. The role of androgen and its related signals in PCOS. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 1825–1837.

- Sanchez-Garrido, M.A.; Tena-Sempere, M. Metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathogenic role of androgen excess and potential therapeutic strategies. Mol. Metab. 2020, 35, 100937.

- Giampaolino, P.; Foreste, V.; Di Filippo, C.; Gallo, A.; Mercorio, A.; Serafino, P.; Improda, F.; Verrazzo, P.; Zara, G.; Buonfantino, C.; et al. Microbiome and PCOS: State-Of-Art and Future Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2048.

- Cao, X.; Liu, X.M.; Zhou, L.H. Recent Progress in Research on the Distribution and Function of NUCB2/Nesfatin-1 in Peripheral Tissues. Endocr. J. 2013, 60.

- Oh-I, S.; Shimizu, H.; Satoh, T.; Okada, S.; Adachi, S.; Inoue, K.; Eguchi, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Imaki, T.; Hashimoto, K.; et al. Identification of nesfatin-1 as a satiety molecule in the hypothalamus. Nature 2006, 443, 709–712.

- Ademoglu, E.N.; Gorar, S.; Carlioglu, A.; Yazıcı, H.; Dellal, F.D.; Berberoglu, Z.; Akdeniz, D.; Uysal, S.; Karakurt, F.; Carlıoglu, A. Plasma nesfatin-1 levels are increased in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2014, 37, 715–719.

- Stengel, A.; Taché, Y. Regulation of Food Intake: The Gastric X/A-like Endocrine Cell in the Spotlight. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2009, 11, 448–454.

- Stengel, A.; Goebel, M.; Yakubov, I.; Wang, L.; Witcher, D.; Coskun, T.; Taché, Y.; Sachs, G.; Lambrecht, N.W.G. Identification and Characterization of Nesfatin-1 Immunoreactivity in Endocrine Cell Types of the Rat Gastric Oxyntic Mucosa. Endocrinol. 2009, 150, 232–238.

- Gonzalez, R.; Tiwari, A.; Unniappan, S. Pancreatic beta cells colocalize insulin and pronesfatin immunoreactivity in rodents. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 381, 643–648.

- Buchanan, C.M.; Phillips, A.R.; Cooper, G. Preptin derived from proinsulin-like growth factor II (proIGF-II) is secreted from pancreatic islet β-cells and enhances insulin secretion. Biochem. J. 2001, 360, 431–439.

- Van Doorn, J. Insulin-like Growth Factor-II and Bioactive Proteins Containing a Part of the E-Domain of pro-Insulin-like Growth Factor-II. BioFactors 2020, 46, 563–578.

- Mierzwicka, A.; Bolanowski, M. New peptides players in metabolic disorders. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej 2016, 70, 881–886.

- Mierzwicka, A.; Kuliczkowska-Plaksej, J.; Kolačkov, K.; Bolanowski, M. Preptin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2018, 34, 470–475.

- Celik, O.; Celik, N.; Hascalik, S.; Sahin, I.; Aydin, S.; Ozerol, E. An appraisal of serum preptin levels in PCOS. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 314–316.

- Ali, H.A.; Abbas, H.J.; Naser, N.A. Preptin and Adropin Levels as New Predictor in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2018, 10, 3005–3008.

- Celik, N.; Aydin, S.; Ugur, K.; Yardim, M.; Acet, M.; Yavuzkir, S.; Sahin, İ.; Celik, O. Patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3-gene (adiponutrin), preptin, kisspeptin and amylin regulates oocyte developmental capacity in PCOS. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 7–12.

- Şentürk, Ş.; Hatirnaz, S.; Kanat-Pektaş, M. Serum Preptin and Amylin Levels with Respect to Body Mass Index in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 7517–7523.

- Bu, Z.; Kuok, K.; Meng, J.; Wang, R.; Xu, B.; Zhang, H. The relationship between polycystic ovary syndrome, glucose tolerance status and serum preptin level. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012, 10, 10.

- Seldin, M.M.; Peterson, J.M.; Byerly, M.S.; Wei, Z.; Wong, G.W. Myonectin (CTRP15), a Novel Myokine That Links Skeletal Muscle to Systemic Lipid Homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 11968–11980.

- Seldin, M.M.; Tan, S.Y.; Wong, G.W. Metabolic function of the CTRP family of hormones. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2013, 15, 111–123.

- Fang, H.; Judd, R.L. Adiponectin Regulation and Function. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1031–1063.

- Li, S.; Huang, X.; Zhong, H.; Peng, Q.; Chen, S.; Xie, Y.; Qin, X.; Qin, A. Low circulating adiponectin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: An updated meta-analysis. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 3961–3973.

- Toulis, K.; Goulis, D.; Farmakiotis, D.; Georgopoulos, N.; Katsikis, I.; Tarlatzis, B.; Papadimas, I.; Panidis, D. Adiponectin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2009, 15, 297–307.

- Anithasri, A.; Ananthanarayanan, P.H.; Veena, P. A Study on Omentin-1 and Prostate Specific Antigen in Women on Treatment for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 34, 108–114.

- Yang, R.-Z.; Lee, M.-J.; Hu, H.; Pray, J.; Wu, H.-B.; Hansen, B.C.; Shuldiner, A.R.; Fried, S.K.; McLenithan, J.C.; Gong, D.-W. Identification of omentin as a novel depot-specific adipokine in human adipose tissue: Possible role in modulating insulin action. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 290, E1253–E1261.

- Fain, J.N.; Sacks, H.S.; Buehrer, B.; Bahouth, S.W.; Garrett, E.; Wolf, R.Y.; Carter, R.A.; Tichansky, D.S.; Madan, A.K. Identification of omentin mRNA in human epicardial adipose tissue: Comparison to omentin in subcutaneous, internal mammary artery periadventitial and visceral abdominal depots. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 810–815.

- De Souza Batista, C.M.; Yang, R.-Z.; Lee, M.-J.; Glynn, N.M.; Yu, D.-Z.; Pray, J.; Ndubuizu, K.; Patil, S.; Schwartz, A.; Kligman, M.; et al. Omentin Plasma Levels and Gene Expression Are Decreased in Obesity. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1655–1661.

- Tan, B.K.; Adya, R.; Farhatullah, S.; Chen, J.; Lehnert, H.; Randeva, H.S. Metformin Treatment May Increase Omentin-1 Levels in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Diabetes 2010, 59, 3023–3031.

- Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Catalán, V.; Ortega, F.; Gómez-Ambrosi, J.; Ricart, W.; Frühbeck, G.; Fernández-Real, J.M. Circulating omentin concentration increases after weight loss. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 7, 27.

- Yamawaki, H.; Kuramoto, J.; Kameshima, S.; Usui, T.; Okada, M.; Hara, Y. Omentin, a novel adipocytokine inhibits TNF-induced vascular inflammation in human endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 408, 339–343.

- Zhou, J.-Y.; Chan, L.; Zhou, S.-W. Omentin: Linking metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 136–143.

- Kazama, K.; Usui, T.; Okada, M.; Hara, Y.; Yamawaki, H. Omentin plays an anti-inflammatory role through inhibition of TNF-α-induced superoxide production in vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 686, 116–123.

- Nolan, K.; Kattamuri, C.; Rankin, S.A.; Read, R.J.; Zorn, A.M.; Thompson, T.B. Structure of Gremlin-2 in Complex with GDF5 Gives Insight into DAN-Family-Mediated BMP Antagonism. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 2077–2086.

- Kisonaite, M.; Wang, X.; Hyvönen, M. Structure of Gremlin-1 and analysis of its interaction with BMP. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 1593–1604.

- Chen, D.; Zhao, M.; Mundy, G.R. Bone Morphogenetic Proteins. Growth Factors 2004, 22, 233–241.

More