Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Yvaine Wei and Version 1 by Jaydira Del Rivero.

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (together PPGL) are rare neuroendocrine tumors that arise from chromaffin tissue and produce catecholamines. Approximately 40% of cases of PPGL carry a germline mutation, suggesting that they have a high degree of heritability. The underlying mutation influences the PPGL clinical presentation such as cell differentiation, specific catecholamine production, tumor location, malignant potential and genetic anticipation, which helps to better understand the clinical course and tailor treatment accordingly. Genetic testing for pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma allows an early detection of hereditary syndromes and facilitates a close follow-up of high-risk patients.

- pheochromocytoma

- paraganglioma

- genetics

- germline

- screening

1. Introduction

Pheochromocytomas (PHEOs) and paragangliomas (PGLs) are rare neuroendocrine (NE) tumors arising from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and extra-adrenal ganglia, respectively. The incidence of PHEOs and PGLs (collectively PPGLs) is estimated at approximately 2–8 cases per million per year [1,2][1][2]. However, this is likely an underestimate, based upon the finding of up to 0.05–0.1% incidentally detected cases in an autopsy series [3]. PPGLs may occur at any age and they usually peak between the 3rd and 5th decade of life [4]. Patients with PPGL most commonly present with symptoms of excess catecholamine production including headache, diaphoresis, palpitations, tremors, facial pallor and hypertension. These symptoms are often paroxysmal, although persistent hypertension between these episodes is common and occurs in 50–60% patients with PPGL [5].

The field of genomics in PPGL has rapidly evolved over the past two decades. Approximately 40% of all cases of PPGLs are associated with germline mutations, which makes pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma solid tumors with a high heritability rate. Currently, more than 20 susceptibility genes have been identified, including at least 12 distinct genetic syndromes, 15 driver genes and an expanding fraction of potential disease modifying genes [11,12][6][7]. Thus, the underlying mutations appear to determine the clinical manifestations, such as tumor location, biochemical profile, malignant potential, imaging signature and overall prognosis, that should help to tailor treatment and guidance for follow-up. Moreover, detection of a mutation in an index case and their family members should also help clinicians to implement a pertinent surveillance program to promptly identify tumors and treat patients accordingly [13,14][8][9]. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment. In cases where surgery is not feasible or if tumor dissemination limits the probability of curative treatment, the options for treatment are localized radiotherapy, radiofrequency or cryoablation and systemic therapy, which includes chemotherapy or targeted molecular therapies.

There has been increasing interest in radionuclide therapy, which includes 131I-MIBG therapy and recently PRRT (peptide receptor radionuclide therapy) 177Lu-DOTATATE [15,16,17][10][11][12]. In terms of chemotherapy, CVD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine) is one of the most traditional chemotherapy regimens and has been used to treat PPGLs over the past 30 years [18][13]. New treatments are emerging for patients with advanced/metastatic PPGL. Understanding the molecular signaling and metabolomics of PPGL has led to the development of therapeutic regimens for cluster-specific targeted molecular therapies. Based on TCGA classification for cluster I, antiangiogenic therapy, HIF inhibitors, PARP (polyADP-ribose polymerase) inhibition and immunotherapy are used. For cluster II, mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors are used. Currently there are no cluster III Wnt signaling targeted therapies for PPGL patients [19][14].

At present, clinical genetic testing for patients with a suspected hereditary form of PPGL is carried out using a germline genetic panel rather than using one gene at a time. Based upon its lower financial cost, immunohistochemistry (IHC) can be considered for screening purposes, particularly in patients with suspected succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDHx) mutations. However, IHC should be interpreted with caution as there is likelihood of false-positive and false-negative results [20][15].

2. Genetics on What Is Already Known

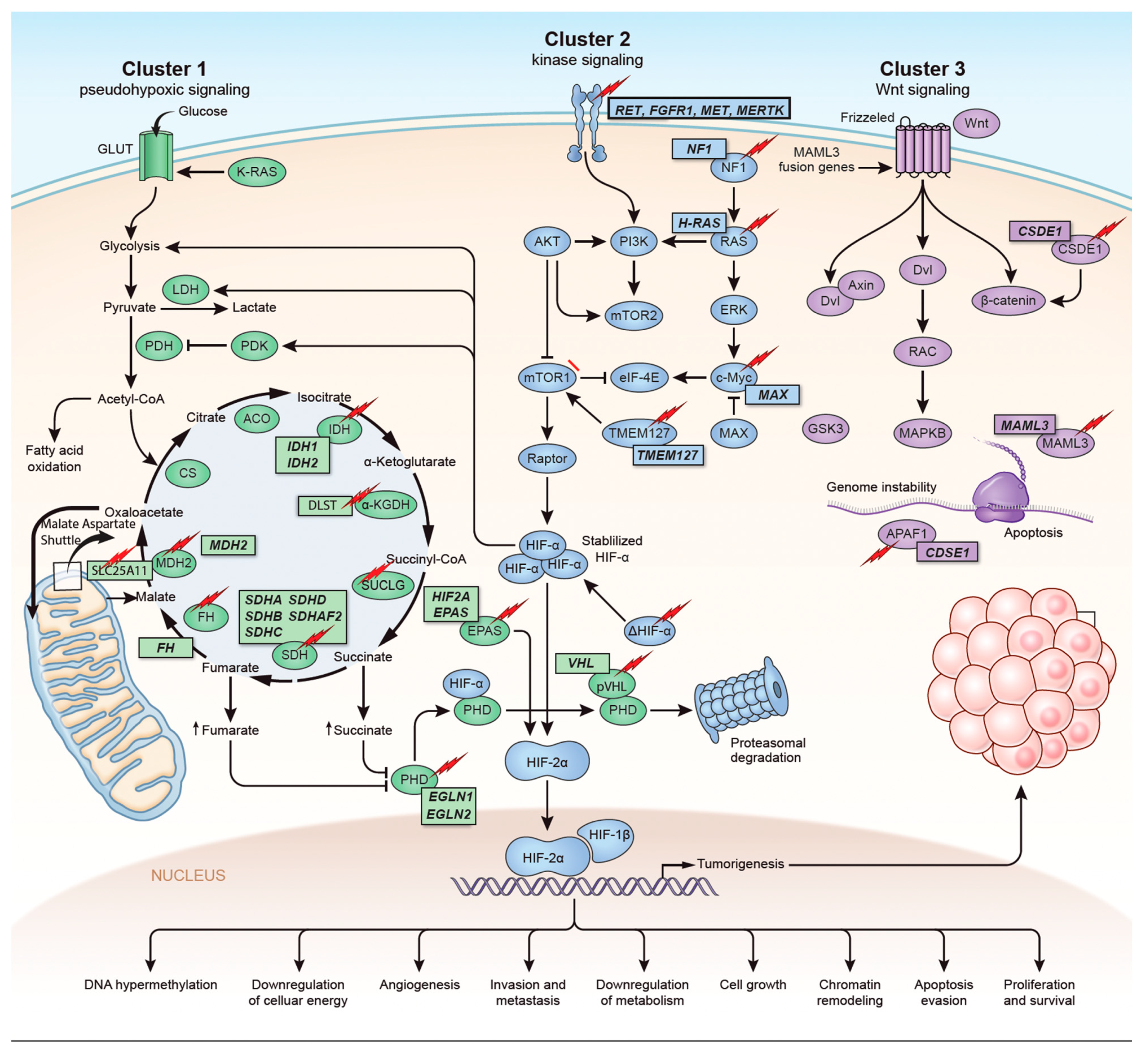

The identification of the Krebs cycle in the etiology of PPGLs is a milestone in the field of the genetics of PPGLs. The SDH complex plays a pivotal role in energy metabolism in the Krebs cycle, as well as in complex II of the electron transport chain. Mutations in any of the genes encoding the catalytic enzymes of the pathway can lead to an accumulation of their substrates, resulting in hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) stability and tumorigenesis [22][16]. These genes include SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SDHAF2 [23 [17][18],24], fumarate hydratase (FH) [25[19][20],26], malate dehydrogenase 2 (MDH2) [27,28][21][22], hypoxia-inducible factor alpha (HIF2a) [29[23][24][25],30,31], prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) [32][26] and some newly discovered genes. Mutation of the genes involved in the kinase receptor signaling pathway that are known to cause PPGLs are RET (REarranged during Transfection), neurofibromin 1 (NF1), Myelocytomatosis-Associated factor X (MAX), transmembrane protein 127 (TMEM127), and Harvey rat sarcoma viral gene homologue (HRAS). Genes such as ATRX (Alpha Thalassemia/mental Retardation-X linked) that are involved in chromosomal integrity, are also implicated as drivers in the etiology of PPGLs and are associated with aggressive behavior [33][27]. To better understand the genetics based on signaling pathways, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has classified PPGLs into three clinically useful molecular clusters: (1) Pseudohypoxic PPGLs, (2) Kinase signaling PPGLs and (3) Wnt signaling PPGLs [34][28] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Genetics and molecular pathways for pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. The genes are classified into three clusters. Cluster I involves mutations in the pseudohypoxic pathway (SDHx, FH, MDH2, HIF2, PHD, VHL and EPAS). Cluster II involves mutations in the kinase signaling group (RET, NF1, TMEM127, MAX and HRAS). Lastly, cluster III includes mutations in the Wnt signaling group (CSDE1 and UBTF fusion at MAML3). The new genes discovered (SUCLG2, SLC25A11, DLST, MAPK, MET, MERTK, FGFR1) have been depicted as well. ↑ depicts accumulation of substrate. Adapted from ref. [19].

Figure 1. Genetics and molecular pathways for pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. The genes are classified into three clusters. Cluster I involves mutations in the pseudohypoxic pathway (SDHx, FH, MDH2, HIF2, PHD, VHL and EPAS). Cluster II involves mutations in the kinase signaling group (RET, NF1, TMEM127, MAX and HRAS). Lastly, cluster III includes mutations in the Wnt signaling group (CSDE1 and UBTF fusion at MAML3). The new genes discovered (SUCLG2, SLC25A11, DLST, MAPK, MET, MERTK, FGFR1) have been depicted as well. ↑ depicts accumulation of substrate. Adapted from ref. [19].Figure 1. Genetics and molecular pathways for pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. The genes are classified into three clusters. Cluster I involves mutations in the pseudohypoxic pathway (SDHx, FH, MDH2, HIF2, PHD, VHL and EPAS). Cluster II involves mutations in the kinase signaling group (RET, NF1, TMEM127, MAX and HRAS). Lastly, cluster III includes mutations in the Wnt signaling group (CSDE1 and UBTF fusion at MAML3). The new genes discovered (SUCLG2, SLC25A11, DLST, MAPK, MET, MERTK, FGFR1) have been depicted as well. ↑ depicts accumulation of substrate. Adapted from ref. [19].

3. Genes Discovered in the Last Five Years

With the expanding genetic landscape of PPGLs, several new genes have been identified recently (Table 1) which can potentially predispose patients to the development of tumors with characteristic biological behaviors.

Table 1.

Newly discovered in the pathogenesis of PPGLs.

| Gene | Year of Discovery | Pathophysiology | Gene Type | Metabolomics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSDE1 | 2016 | Tumor suppressor gene involved in mRNA stability and cellular apoptosis | Somatic | Adrenergic | [6,7][29][30] |

| H3F3A | 2016 | Encodes histone H3.3 protein that regulates chromatin formation | Somatic | NA | [35,36][31][32] |

| MET | 2016 | MAPK signaling pathway | Germline, somatic | NA | [23][17] |

| MERTK | 2016 | Tyrosine kinase receptor | Germline | NA | [11,37,38][6][33][34] |

| UBTF-MAML3 | 2017 | Unique methylation profile mRNA overexpression involved in Wnt receptor and hedgehog signaling pathways | Fusion | Adrenergic | [6,39][29][35] |

| SLC25A11 | 2018 | Encodes malate-oxalate carrier protein of malate-aspartate shuttle | Germline | Noradrenergic | [40,41][36][37] |

| IRP1 | 2018 | Cellular iron metabolism regulation | Somatic | noradrenergic | [42][38] |

| DLST | 2019 | Encodes E2 subunit of mitochondrial α -KG complex which converts α-KG to succinyl-CoA | Germline | Noradrenergic | [23,43][17][39] |

| SUCLG2 | 2021 | Catalyzes conversion of succinyl-coA and ADP/GTP to succinate and ATP/GTP | Germline | Noradrenergic | [44][40] |

4. New Screening Guidelines for Asymptomatic SDHx Carriers

Germline mutations in SDHx comprises approximately 20% of cases of PPGL [10,57,58][41][42][43]. When a SDHx pathogenic mutation is identified, genetic counselling is proposed for patients’ first-degree relatives. However, there are no established guidelines on how to screen and then follow up asymptomatic mutation carriers. The penetrance of SDHx-related PPGL is not firmly established. Studies have shown that SDHB has a 8–37% penetrance and SDHD has a 38–64% penetrance [21,59][44][45]. Out of all SDHx mutation carriers, patients with an SDHB mutation carry the highest risk for metastatic disease [58,60,61][43][46][47]. Patients with SDHD mutations have the highest penetrance. Data regarding SDHC and SDHA mutations are limited but show lower penetrance than SDHD mutation carriers [58,62,63][43][48][49].5. Emerging Molecular Genetics and Future Perspectives

The clinical treatment options for patients with PPGL are increasingly based on the underlying molecular biology, genetic and epigenetic analyses of the tumors. Over the last five years, various human- and rodent-derived cell lines and xenografts have been developed. Yet, they do not fully provide subtype classification of tumors and remain challenging for clinical studies. Frankhauser et al. used “immortalized mouse chromaffin cells” (imCCs), MPC/MTT (mouse pheochromocytoma cells/mouse tumor tissue) spheroids, murine pheochromocytoma cell lines and human pheochromocytoma primary cultures, and identified that the PI3Ka inhibitor BYL719 and the MTORC1 inhibitor everolimus are highly effective at tumor shrinkage at clinically relevant doses [76][50]. To date, there has only been one human cell line progenitor developed successfully: Pheo1 [77][51]. Moreover, the classic approaches to cell line development, such as SV40-mediated immortalization and newer approaches such as patient-derived tumor xenografts and tumor organoids, have become important preclinical models. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are worth exploring further in this field [78,79][52][53].6. Conclusions

PPGLs are rare NE tumors with unique molecular landscapes. Cataloging and understanding the germline and somatic mutations associated with PPGLs is a promising approach to understand the clinical behavior and prognosis. Moreover, it can provide guidance on diagnostic strategies and personalized treatments for PPGLs.References

- Beard, C.M.; Sheps, S.G.; Kurland, L.T.; Carney, J.A.; Lie, J.T. Occurrence of pheochromocytoma in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950 through 1979. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1983, 58, 802–804.

- Chen, H.; Sippel, R.S.; O’Dorisio, M.S.; Vinik, A.I.; Lloyd, R.V.; Pacak, K. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: Pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and medullary thyroid cancer. Pancreas 2010, 39, 775–783.

- Sutton, M.G.; Sheps, S.G.; Lie, J.T. Prevalence of clinically unsuspected pheochromocytoma. Review of a 50-year autopsy series. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1981, 56, 354–360.

- Guerrero, M.A.; Schreinemakers, J.M.; Vriens, M.R.; Suh, I.; Hwang, J.; Shen, W.T.; Gosnell, J.; Clark, O.H.; Duh, Q.-Y. Clinical Spectrum of Pheochromocytoma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2009, 209, 727–732.

- Lenders, J.W.; Eisenhofer, G.; Mannelli, M.; Pacak, K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet 2005, 366, 665–675.

- Dahia, P.L.M. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma pathogenesis: Learning from genetic heterogeneity. Nat. Cancer 2014, 14, 108–119.

- Favier, J.; Amar, L.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: From genetics to personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 101–111.

- King, K.S.; Prodanov, T.; Kantorovich, V.; Fojo, T.; Hewitt, J.; Zacharin, M.; Wesley, R.; Lodish, M.; Raygada, M.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P.; et al. Metastatic Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma Related to Primary Tumor Development in Childhood or Adolescence: Significant Link to SDHB Mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4137–4142.

- Shuch, B.; Ricketts, C.J.; Metwalli, A.R.; Pacak, K.; Linehan, W.M. The Genetic Basis of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Implications for Management. Urology 2014, 83, 1225–1232.

- Mak, I.Y.F.; Hayes, A.; Khoo, B.; Grossman, A. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy as a Novel Treatment for Metastatic and Invasive Phaeochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Neuroendocrinology 2019, 109, 287–298.

- Kong, G.; Grozinsky-Glasberg, S.; Hofman, M.; Callahan, J.; Meirovitz, A.; Maimon, O.; Pattison, D.; Gross, D.J.; Hicks, R. Efficacy of Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy for Functional Metastatic Paraganglioma and Pheochromocytoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3278–3287.

- Yadav, M.P.; Ballal, S.; Bal, C. Concomitant 177Lu-DOTATATE and capecitabine therapy in malignant paragangliomas. EJNMMI Res. 2019, 9, 13.

- Huang, H.; Abraham, J.; Hung, E.; Averbuch, S.; Merino, M.J.; Steinberg, S.M.; Pacak, K.; Fojo, T. Treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine. Cancer 2008, 113, 2020–2028.

- Ilanchezhian, M.; Jha, A.; Pacak, K.; Del Rivero, J. Emerging Treatments for Advanced/Metastatic Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2020, 21, 85.

- Castelblanco, E.; Santacana, M.; Valls, J.; de Cubas, A.; Cascón, A.; Robledo, M.; Matias-Guiu, X. Usefulness of Negative and Weak–Diffuse Pattern of SDHB Immunostaining in Assessment of SDH Mutations in Paragangliomas and Pheochromocytomas. Endocr. Pathol. 2013, 24, 199–205.

- King, A.; Selak, M.A.; Gottlieb, E. Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate hydratase: Linking mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4675–4682.

- Toledo, R.; Qin, Y.; Cheng, Z.-M.; Gao, Q.; Iwata, S.; Silva, G.M.; Prasad, M.L.; Ocal, I.T.; Rao, S.; Aronin, N.; et al. Recurrent Mutations of Chromatin-Remodeling Genes and Kinase Receptors in Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2301–2310.

- Kunst, H.P.; Rutten, M.H.; De Mönnink, J.-P.; Hoefsloot, L.H.; Timmers, H.J.; Marres, H.A.; Jansen, J.; Kremer, H.; Bayley, J.-P.; Cremers, C.W. SDHAF2 (PGL2-SDH5) and Hereditary Head and Neck Paraganglioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 247–254.

- Castro-Vega, L.J.; Buffet, A.; De Cubas, A.A.; Cascón, A.; Menara, M.; Khalifa, E.; Amar, L.; Azriel, S.; Bourdeau, I.; Chabre, O.; et al. Germline mutations in FH confer predisposition to malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 2440–2446.

- Clark, G.R.; Sciacovelli, M.; Gaude, E.; Walsh, D.M.; Kirby, G.; Simpson, M.; Trembath, R.; Berg, J.N.; Woodward, E.R.; Kinning, E.; et al. Germline FH Mutations Presenting With Pheochromocytoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E2046–E2050.

- Calsina, B.; Currás-Freixes, M.; Buffet, A.; Pons, T.; Contreras, L.; Letón, R.; Comino-Méndez, I.; Remacha, L.; Calatayud, M.; Obispo, B.; et al. Role of MDH2 pathogenic variant in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma patients. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 1652–1662.

- Cascón, A.; Comino-Méndez, I.; Currás-Freixes, M.; de Cubas, A.A.; Contreras, L.; Richter, S.; Peitzsch, M.; Mancikova, V.; Inglada-Pérez, L.; Pérez-Barrios, A.; et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies MDH2 as a New Familial Paraganglioma Gene. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv053.

- Lorenzo, F.R.; Yang, C.; Ng Tang Fui, M.; Vankayalapati, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Huynh, T.; Grossmann, M.; Pacak, K.; Prchal, J.T. A novel EPAS1/HIF2A germline mutation in a congenital polycythemia with paraganglioma. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 91, 507–512.

- Därr, R.; Nambuba, J.; Del Rivero, J.; Janssen, I.; Merino, M.; Todorovic, M.; Balint, B.; Jochmanova, I.; Prchal, J.T.; Lechan, R.M.; et al. Novel insights into the polycythemia–paraganglioma–somatostatinoma syndrome. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2016, 23, 899–908.

- Pacak, K.; Jochmanova, I.; Prodanov, T.; Yang, C.; Merino, M.J.; Fojo, T.; Prchal, J.T.; Tischler, A.S.; Lechan, R.M.; Zhuang, Z. New Syndrome of Paraganglioma and Somatostatinoma Associated With Polycythemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1690–1698.

- Yang, C.; Zhuang, Z.; Fliedner, S.; Shankavaram, U.; Sun, M.G.; Bullova, P.; Zhu, R.; Elkahloun, A.G.; Kourlas, P.J.; Merino, M.; et al. Germ-line PHD1 and PHD2 mutations detected in patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma-polycythemia. Klin. Wochenschr. 2015, 93, 93–104.

- Fishbein, L.; Khare, S.; Wubbenhorst, B.; Desloover, D.; D’Andrea, K.; Merrill, S.; Cho, N.W.; Greenberg, R.A.; Else, T.; Montone, K.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic ATRX mutations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6140.

- Crona, J.; Taïeb, D.; Pacak, K. New Perspectives on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Toward a Molecular Classification. Endocr. Rev. 2017, 38, 489–515.

- Fishbein, L.; Leshchiner, I.; Walter, V.; Danilova, L.; Robertson, A.G.; Johnson, A.R.; Lichtenberg, T.M.; Murray, B.A.; Ghayee, H.K.; Else, T.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 181–193.

- Jochmanova, I.; Pacak, K. Genomic Landscape of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 6–9.

- Greer, E.L.; Shi, Y. Histone methylation: A dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 343–357.

- Iwata, S.; Yonemoto, T.; Ishii, T.; Araki, A.; Hagiwara, Y.; Tatezaki, S.I. Multicentric Giant Cell Tumor of Bone and Paraganglioma: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect. 2013, 3, e23.

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data: Figure 1. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404.

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, pl1.

- Miao, C.-G.; Shi, W.-J.; Xiong, Y.-Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.-L.; Qin, M.-S.; Du, C.-L.; Song, T.-W.; Li, J. miR-375 regulates the canonical Wnt pathway through FZD8 silencing in arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Immunol. Lett. 2015, 164, 1–10.

- Buffet, A.; Morin, A.; Castro-Vega, L.J.; Habarou, F.; Lussey-Lepoutre, C.; Letouze, E.; Lefebvre, H.; Guilhem, I.; Haissaguerre, M.; Raingeard, I.; et al. Germline Mutations in the Mitochondrial 2-Oxoglutarate/Malate Carrier SLC25A11 Gene Confer a Predisposition to Metastatic Paragangliomas. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1914–1922.

- Monné, M.; Palmieri, F. Antiporters of the Mitochondrial Carrier Family. Chloride Channels 2014, 73, 289–320.

- Pang, Y.; Gupta, G.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Huynh, T.-T.; Abdullaev, Z.; Pack, S.D.; Percy, M.J.; Lappin, T.R.J.; Zhuang, Z.; et al. A novel splicing site IRP1 somatic mutation in a patient with pheochromocytoma and JAK2V617F positive polycythemia vera: A case report. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 286.

- Remacha, L.; Pirman, D.; Mahoney, C.E.; Coloma, J.; Calsina, B.; Currás-Freixes, M.; Letón, R.; Torres-Pérez, R.; Richter, S.; Pita, G.; et al. Recurrent Germline DLST Mutations in Individuals with Multiple Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 1008–1010.

- Vanova, K.H.; Pang, Y.; Krobova, L.; Kraus, M.; Nahacka, Z.; Boukalova, S.; Pack, S.D.; Zobalova, R.; Zhu, J.; Huynh, T.-T.; et al. Germline SUCLG2 Variants in Patients With Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 114, 130–138.

- Lenders, J.W.M.; Duh, Q.-Y.; Eisenhofer, G.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P.; Grebe, S.K.G.; Murad, M.H.; Naruse, M.; Pacak, K.; Young, W.F. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 1915–1942.

- Ben Aim, L.; Pigny, P.; Castro-Vega, L.J.; Buffet, A.; Amar, L.; Bertherat, J.; Drui, D.; Guilhem, I.; Baudin, E.; Lussey-Lepoutre, C.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing detects rare genetic events in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 513–520.

- Andrews, K.A.; Ascher, D.B.; Pires, D.E.V.; Barnes, D.R.; Vialard, L.; Casey, R.T.; Bradshaw, N.; Adlard, J.; Aylwin, S.; Brennan, P.; et al. Tumour risks and genotype-phenotype correlations associated with germline variants in succinate dehydrogenase subunit genes SDHB, SDHC and SDHD. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 55, 384–394.

- Amar, L.; Pacak, K.; Steichen, O.; Akker, S.A.; Aylwin, S.J.B.; Baudin, E.; Buffet, A.; Burnichon, N.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Dahia, P.L.M.; et al. International consensus on initial screening and follow-up of asymptomatic SDHx mutation carriers. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 435–444.

- Marikian, G.G.; Ambartsumian, T.G.; Adamian, S.I. Ouabain-insensitive K+ and Na+ fluxes in frog muscle. Biofizika 1983, 28, 1019–1021.

- Benn, D.E.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P.; Reilly, J.; Bertherat, J.; Burgess, J.; Byth, K.; Croxson, M.; Dahia, P.L.M.; Elston, M.; Gimm, O.; et al. Clinical Presentation and Penetrance of Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma Syndromes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 827–836.

- Amar, L.; Baudin, E.; Burnichon, N.; Peyrard, S.; Silvera, S.; Bertherat, J.; Bertagna, X.; Schlumberger, M.; Jeunemaitre, X.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P.; et al. Succinate Dehydrogenase B Gene Mutations Predict Survival in Patients with Malignant Pheochromocytomas or Paragangliomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 3822–3828.

- Neumann, H.P.; Pawlu, C.; Peczkowska, M.; Bausch, B.; McWhinney, S.R.; Muresan, M.; Buchta, M.; Franke, G.; Klisch, J.; Bley, T.A.; et al. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA 2004, 292, 943–951.

- Bourdeau, I.; Grunenwald, S.; Burnichon, N.; Khalifa, E.; Dumas, N.; Binet, M.-C.; Nolet, S.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P. A SDHC Founder Mutation Causes Paragangliomas (PGLs) in the French Canadians: New Insights on the SDHC-Related PGL. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 4710–4718.

- Fankhauser, M.; Bechmann, N.; Lauseker, M.; Goncalves, J.; Favier, J.; Klink, B.; William, D.; Gieldon, L.; Maurer, J.; Spöttl, G.; et al. Synergistic Highly Potent Targeted Drug Combinations in Different Pheochromocytoma Models Including Human Tumor Cultures. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 2600–2617.

- Ghayee, H.K.; Bhagwandin, V.J.; Stastny, V.; Click, A.; Ding, L.-H.; Mizrachi, D.; Zou, Y.; Chari, R.; Lam, W.L.; Bachoo, R.M.; et al. Progenitor Cell Line (hPheo1) Derived from a Human Pheochromocytoma Tumor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65624.

- Suga, H. Application of pluripotent stem cells for treatment of human neuroendocrine disorders. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 2018, 375, 267–278.

- Bleijs, M.; Van De Wetering, M.; Clevers, H.; Drost, J. Xenograft and organoid model systems in cancer research. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e101654.

More