Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 4 by Beatrix Zheng and Version 6 by Beatrix Zheng.

Since there is no gold standard for screening tests, physicians should (or should not) order them based on a tailor-made approach to each AIT candidate, taking under consideration contraindications and the predictive value of each test. Undoubtedly, more research is required in order to establish a universal approach.

- allergen immunotherapy

- venom immunotherapy

- contraindications

- allergy diagnosis

- autoimmune diseases

- neoplasias

- cardiovascular disease

- HIV

- allergy tests

1. Introduction

Allergen Immunotherapy (AIT) is a well-established treatment option for respiratory and insect-venom allergies, as well as the only etiology-based and disease-modifying treatment for allergic diseases [1][2][3][4]. The administration of AIT is indicated for the treatment of allergic rhinitis, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and allergic asthma, and is efficacious when directed at the specific allergen-driving symptoms [1][3][4][5][6]. Venom immunotherapy (VIT) is recommended for children and adults following a systemic allergic reaction to insect stings that exceeds generalized cutaneous symptoms [6][7][8].

Allergic reactions induced by AIT administration are common adverse events. The frequency of systemic adverse events is 8–20% for patients receiving VIT and 2.1% for patients (or 0.2% of the injections) receiving subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) for airborne allergens [6][7][8][9]. The sublingual route of AIT for respiratory allergies (SLIT) appears to be a safer option with only 1.1% of patients reporting adverse events [8][9]. Local reactions at the injection site, that resolve spontaneously, are the main side effect of subcutaneous AIT, ranging from 0.7–4% of the injections [3][6]. Local reactions at the oral mucosa can be observed in the case of SLIT [3]. Although systemic allergic reactions are a significant concern during AIT, the risk of anaphylaxis can be minimized when well-trained allergologists and other healthcare professionals follow standard protocols [6]. Further, the prompt recognition and management of the potential reaction is a crucial step [3][4][6].

Although acute reactions remain the most common side effects of AIT, close attention should be paid to slowly evolving reactions that might appear as an interaction of AIT with the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of certain health conditions. The administration of AIT is contraindicated in cases where certain concomitant diseases or conditions are present; however, controversy exists on what the contraindications are, on the level of evidence for their consideration as contraindications and on whether they are relative or absolute [10][11]. On the other hand, the administration of AIT appears to be safe and well tolerated in certain patient groups with high-risk conditions such as cardiovascular disease, those undergoing treatment with ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, and patients with malignant diseases in remission or organ-specific autoimmune diseases, [11].

National and international guidelines are valuable tools for clinicians, describing the indications and contraindications of AIT, although differences might exist among them [10]. Following the identification of the culprit antigen that correlates with the suspected triggers and patient exposure, AIT can be prescribed to the patient [5][7]. A thorough history and clinical examination can provide information regarding contraindications.

It is worth noting that several clinicians and institutions follow the practice of ordering screening tests based on conditions that are considered contraindications. The practice of ordering a battery of tests is not supported by current guidelines and is based upon the clinician’s discretion. Confirmation of the positive allergy skin tests by serum-specific IgE (sIgE) is an example of a workup that is practiced by many allergy centers before prescribing initial AIT, although the guidelines do not suggest it [5][6]. A complete blood count and peripheral smear examination are common laboratory tests used as a routine health checkup of a healthy person and are also used by several institutions as a screening tool for AIT candidates.

Anamnesis is crucial to decide if AIT is a safe choice for our patient and a workup is some times necessary to confirm/exclude health concerns suspected during patient's history. In the full version of the researchers' assessment of cardiovascular problems, neoplasias, auto-immune diseases, HIV and primary immunodeficiencies are described [12].

2. Laboratory Tests Confirming IgE-Mediated Allergy and Monitoring the Severity of the Allergic Reaction

2.1. Skin Tests

Skin tests are the cornerstone of allergy diagnostic evaluation. The skin-prick test (SPT) is a cheap, quick and easy-to-perform method of diagnosis for IgE-mediated sensitivity to aeroallergens and Hymenoptera venoms [13]. In the case of Hymenoptera-venom allergy, the SPT is followed by the performance of intradermal tests [14]. Regarding the respiratory allergy evaluation, the SPT is performed using a panel of standard allergen extracts, including the local major aeroallergens [13]. In the case of venom hypersensitivity, skin tests are performed with the use of locally offending insects. In Europe, Apis melifera, Vespula, Polistes and Dolichovespula venom extracts are widely used [14].2.2. Serum-IgE Tests

The published guidelines recommend the use of serum sIgE as a useful test under certain circumstances or as an alternative to the SPT [5][6][7]. There is no doubt that the use of both the SPT and sIgE increases the diagnostic sensitivity [15]. Two-tiered allergen testing by two independent diagnostic tools can increase the confidence in the long-term success of the AIT. The sIgE tests have a “quantitative” value and can replace the SPT in cases of extended dermatosis, in patients taking histamine-blocking drugs, or in non-cooperative children [16]. Cautiousness should be paid to the interpretation of sIgE in the case of high total serum IgE; in this case, the detection of low specific-IgE levels is often of doubtful clinical relevance [13]. Combined with total IgE, the use of sIgE has also been proposed as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of AIT, but its utility has not been properly evaluated or validated [17].2.3. Component-Resolved Diagnostics (CRD)

Allergen cross-reactivity, defined as the immunologic recognition of different antigens by the same IgE, is a frequent phenomenon observed among the pollen of taxonomically related plants [16]. Cross-reactivity is also observed for homologous molecules that are widely distributed in evolutionarily unrelated species, namely panallergens. When patients are skin- and sIgE-tested, cross-reactivity with the false-positive tests of homologous allergens without clinical relevance may occur [18]. A polysensitized patient is not always poly-allergic; polysensitization is the presentation of multiple positive (sensitivities to) allergy tests, while a poly-allergic patient is also polysensitized but with clinically relevant positive sensitivities. This phenomenon can be observed in both airborne and Hymenoptera-venom allergens, so in the case of polysensitized patients, caution should be paid to detect whether it is a true co-sensitization (true coexisting sensitization to different allergens) and to exclude sensitization to a cross-reactive allergen that is not connected to the clinical symptoms. Recent advances in molecular allergology have provided the opportunity to use component-resolved diagnostics (CRD) to meticulously interpret the allergy tests. CRD offers the possibility to detect “truly symptom-causing” allergen molecules, called marker allergens, that are specific to a pollen or a Hymenoptera-species venom [14]. CRD is often necessary to exclude false-positive tests. An example of CRD as an additional decision tool is its use in grass AIT; the detection of sIgE with any of Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5 or Phl p 11 leads to the safe initiation of AIT, while the co-sensitization to Phl p 5 and Phl p 12 predicts side effects during AIT [18][19]. Examples of allergens associated with cross-sensitivity to Apis mellifera and Vespula vulgaris are hyaluronidases, dipeptidylpeptidase IV and vitellogenins [14]. Sensitization to these allergens can lead to false-positive allergy tests. CRD can also reveal sIgE against cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants that occur in patients sensitized to pollen or venoms without clinical relevance [14].2.4. Tryptase

Patients with mastocytosis, particularly those with clonal-mast-cell-activation syndrome (c-MCAS), are at high risk for anaphylaxis after a field sting [20]. However, patients with aggressive subtypes of systemic mastocytosis and those with urticaria pigmentosa appear not to be at risk of a systemic sting reaction [20][21]. Tryptase is a useful diagnostic tool that is included as a minor criterion in the diagnostic criteria for systemic mastocytosis [22]. A history of severe Hymenoptera-venom anaphylaxis in patients with c-MCAS is predictive of a future severe systemic sting reaction, and VIT is the appropriate therapeutic option regardless of the level of tryptase. A VIT duration longer than the usual 5 years, or even a lifelong duration, is highly advised for these patients [7]. Increased serum-tryptase levels are associated with more frequent and severe systemic reactions to VIT injections, greater treatment-failure rates during VIT treatment and greater relapse rates, including fatal reactions, if VIT is discontinued [6]. The measurement of baseline tryptase is recommended in patients with moderate or severe anaphylactic reactions to stings, in order to detect mastocytosis. It may represent a predictive factor of VIT efficacy and affect the decision regarding the treatment duration [7]. However, elevated tryptase levels may represent an epiphenomenon of the enhanced mast-cell activation and/or relatively increased mast-cell numbers [20].2.5. Basophil-Activation Test

The basophil-activation test (BAT) is a useful technique to establish a diagnosis in several allergy cases for which the common diagnostic tools have failed to accurately identify the culprit allergen. For example, the BAT can be useful in determining a diagnosis in patients with a history of systemic sting reactions, with negative skin and sIgE tests and with a hint of possible mastocytosis [23]. Therefore, it can only be a preliminary-workup diagnostic tool for VIT in rare cases of sting-induced anaphylaxis [24].2.6. Complete Blood Count (CBC)

The CBC includes a hemogram with the enumeration of red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs) and platelets. It is a useful test to evaluate primary diseases of the blood and bone marrow, including anemia, leukemia, polycythemia, thrombocytosis and thrombocytopenia [25]. Furthermore, it is used in the evaluation of disease processes such as infection, inflammation, coagulopathies, neoplasms and exposure to toxic substances [25]. In allergic patients, a CBC with a WBC differential often reveals mild eosinophilia (500–1500 eosinophils per mL) [26]. This is a common finding in patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma and drug-hypersensitivity reactions and no further detection is needed in order to start AIT. Hypereosinophilia (>1500 eos per mL) should be differentiated from eosinophilia, given that it is usually observed in parasitic infections and hypereosinophilic syndromes and rarely in drug allergies. Primary and acquired immunodeficiencies (IDs) are considered relative contraindications for AIT. Several primary IDs are associated with eosinophilia and hypereosinophilia, such as autosomal-dominant hyper-IgE (or Job’s) syndrome, Omenn syndrome, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome and Severe Combined Immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID) [27]. Given the characteristic clinical features and the history of recurrent infections, most patients with primary IDs are diagnosed early in life, therefore, ID is low on the differential-diagnosis list of eosinophilia. Eosinophilia might also occur in immune-dysregulatory syndromes, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, X-linked syndrome with immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy and enteropathy, Loeys–Dietz syndrome and in dermatologic syndromes with immunodysregulation [27]. In conclusion, the evaluation of CBC is an important priority before initiating AIT, since it can detect malignancies as well as medical conditions requiring treatment. On the other hand, the detection of mild eosinophilia in the WBCs of patients with respiratory allergy does not require further blood tests.3. Current Insights

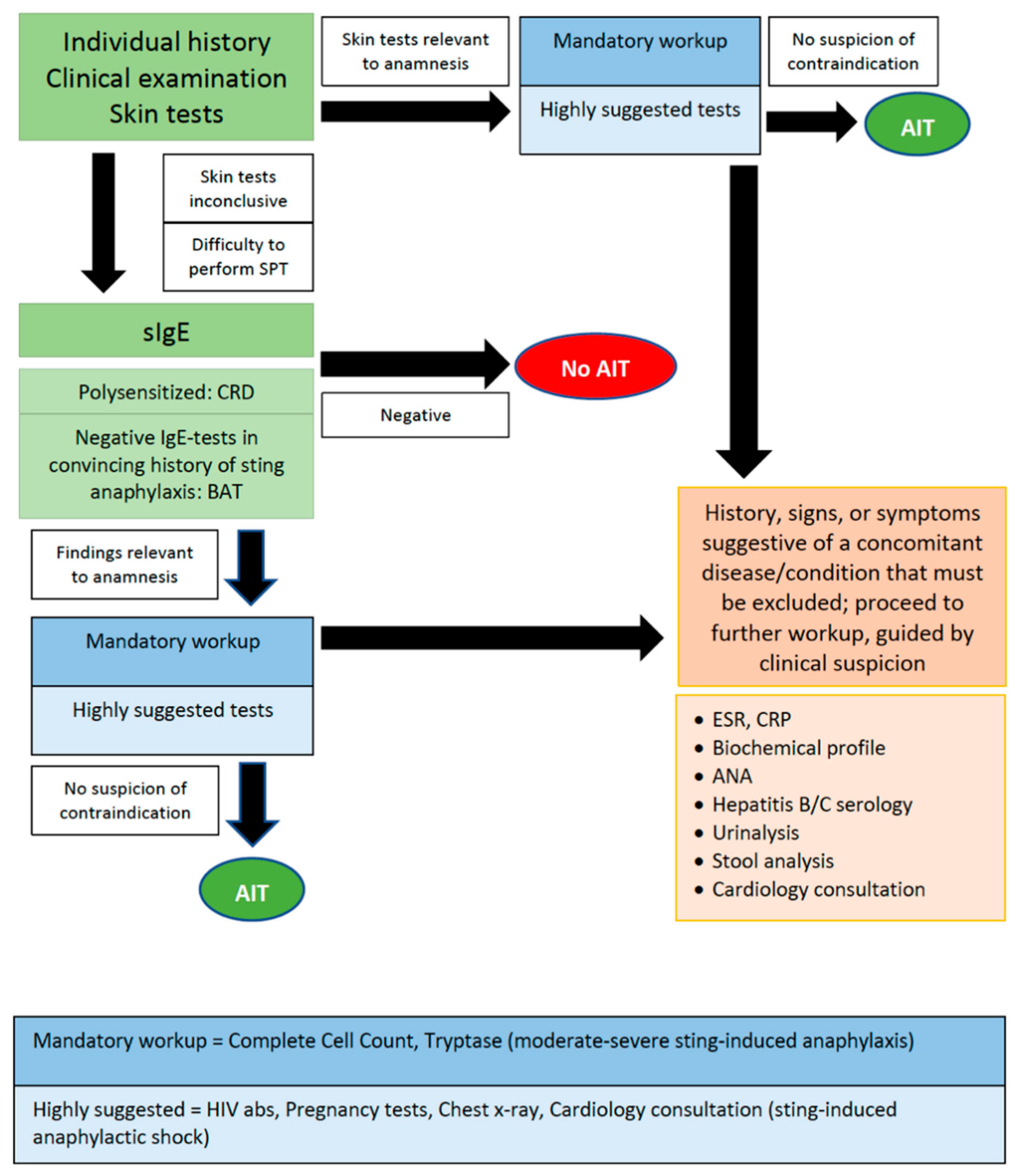

According to the Hippocratic precept, “in illnesses one should keep two things in mind; to do good or to do no harm”. The intention of the physician that prescribes a medicine is to cure, taking care to minimize the manifestation of unwanted adverse reactions. The same intention applies to the administration of AIT that aims to “correct” the way that the human immune system reacts to innocuous antigens, but is avoided if a concomitant disease or health condition may be deteriorated. The use of AIT is a precision-medicine approach for the treatment of respiratory and venom allergy in adults and children. The patient’s thorough anamnesis should be taken before the start of AIT, since the description of clinical symptoms and signs may offer clues suggestive of a concomitant disease, which could affect treatment decisions. For example, the mention of symptoms suggestive of eosinophilic esophagitis discourages the use of SLIT to airborne allergens, while SCIT is considered safer [28]. Allergologists should always be alert to any change in patients’ general health condition throughout the AIT duration. The periodic performance of peak-flow measurement and spirometry is a familiar example of periodical follow-up practice for AIT-treated patients with asthma. Therefore, during AIT visits, besides asking about their allergy symptoms, it is also suggested to ask patients about the general condition of their health. A laboratory workup or a reference to an expert can help to define the diagnosis of suspected diseases. On the other hand, ordering an extended workup without proper justification can be considered as thriftlessness. The cost of an extensive evaluation that is not always approved and covered by public or private insurance providers is a parameter that should be taken under consideration. Proper decision making and considering the impact of each laboratory test sets the basis of cost-effectiveness. However, not all benefits and costs (transportation, out-of-pocket expenses and productivity losses) are health related, so it would be wise to approach patients from a societal perspective as well [29]. Although as physicians we are not always well trained to make cost-effectiveness decisions, we are at least trained to the individual assessment of the risk-benefit ratio; we can decide on the risk vs. benefit when ordering a chest X-ray or further cancer-imaging tests, which expose our patient to radiation [30]. In the research, it was attempted to approach the dilemma of what makes a test or examination helpful before the start of AIT, in the hope of triggering subsequent studies. (Figure 1) [12]. It appears that when the history and physical examination are not conclusive of a safe diagnosis, further investigation is required. In Table 1, an approach on how to proceed with the preliminary workup for AIT candidates is suggested mainly based on the guidelines on contraindications that are currently in effect [5][6][7][31].

Figure 1.

Suggested diagnostic procedure before the start of AIT.

Table 1. Suggestions on how to proceed with workup in candidates for AIT, after having detected the relevant symptom-developing allergen.

| Workup | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| sIgE and total IgE | Optional |

| Molecular sIgE (CRD) | Optional (polysensitized patients) |

| Tryptase | VIT; mandatory in moderate-severe sting-induced anaphylaxis |

| BAT | VIT; optional (exceptional cases of negative IgE-tests) |

| Complete cell count | Mandatory |

| Glucose, BUN, creatinine, AST, ALT, albumin, electrolytes | Optional |

| ESR, CRP | Optional |

| HIV detection | Highly suggested |

| Hepatitis B/C serology | Optional |

| ANA | Highly suggested, only when physical examination reveals characteristic signs and symptoms posing probability of ARD |

| Pregnancy test | Highly suggested in atypical last menstrual period and/or irregular menses |

| Urinalysis | Optional |

| Stool analysis | Optional |

| Chest X-ray | Highly suggested |

| Cardiology consultation | AIT; optional, when cardiologic problems preexist. VIT; highly suggested in history of sting-induced anaphylactic shock. |

References

- Dhami, S.; Kakourou, A.; Asamoah, F.; Agache, I.; Lau, S.; Jutel, M.; Muraro, A.; Roberts, G.; Akdis, C.A.; Bonini, M.; et al. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2017, 72, 1825–1848.

- Bousquet, J.; van Cauwenberge, P.; Khaltaev, N. Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001, 108, S147–S334.

- Nurmatov, U.; Dhami, S.; Arasi, S.; Roberts, G.; Pfaar, O.; Muraro, A.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Calderon, M.; Cingi, C.; Durham, S.; et al. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: A systematic overview of systematic reviews. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2017, 7, 1–16.

- Dhami, S.; Zaman, H.; Varga, E.-M.; Sturm, G.J.; Muraro, A.; Akdis, C.A.; Antolín-Amérigo, D.; Bilò, M.B.; Bokanovic, D.; Calderon, M.A.; et al. Allergen immunotherapy for insect venom allergy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 72, 342–365.

- Roberts, G.; Pfaar, O.; Akdis, C.A.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Durham, S.R.; Van Wijk, R.G.; Halken, S.; Linnemann, D.L.; Pawankar, R.; Pitsios, C.; et al. EAACI Guidelines on Allergen Immunotherapy: Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Allergy 2017, 73, 765–798.

- Cox, L.; Nelson, H.; Lockey, R.; Calabria, C.; Chacko, T.; Finegold, I.; Nelson, M.; Weber, R.; Bernstein, D.I.; Blessing-Moore, J.; et al. Allergen immunotherapy: A practice parameter third update. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, S1–S55.

- Sturm, G.J.; Varga, E.-M.; Roberts, G.; Mosbech, H.; Bilò, M.B.; Akdis, C.A.; Antolín-Amérigo, D.; Cichocka-Jarosz, E.; Gawlik, R.; Jakob, T.; et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy 2017, 73, 744–764.

- Alvaro-Lozano, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Alviani, C.; Angier, E.; Arasi, S.; Arzt-Gradwohl, L.; Barber, D.; Bazire, R.; Cavkaytar, O.; et al. Allergen Immunotherapy in Children User’s Guide. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 1–101.

- Calderón, M.A.; Vidal, C.; del Río, P.R.; Just, J.; Pfaar, O.; Tabar, A.I.; Sánchez-Machín, I.; Bubel, P.; Borja, J.; Eberle, P.; et al. European Survey on Adverse Systemic Reactions in Allergen Immunotherapy (EASSI): A real-life clinical assessment. Allergy 2016, 72, 462–472.

- Pitsios, C.; Tsoumani, M.; Bilò, M.B.; Sturm, G.J.; del Rio, P.R.; Gawlik, R.; Ruëff, F.; Paraskevopoulos, G.; Valovirta, E.; Pfaar, O.; et al. Contraindications to immunotherapy: A global approach. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2019, 9, 1–10.

- Del Rio, P.R.; Pitsios, C.; Tsoumani, M.; Pfaar, O.; Paraskevopoulos, G.; Gawlik, R.; Valovirta, E.; Larenas-Linnemann, D.; Demoly, P.; Calderón, M.A. Physicians’ experience and opinion on contraindications to allergen immunotherapy: The CONSIT survey. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017, 118, 621–628.e1.

- Constantinos Pitsios; Konstantinos Petalas; Anastasia Dimitriou; Konstantinos Parperis; Kyriaki Gerasimidou; Caterina Chliva; Workup and Clinical Assessment for Allergen Immunotherapy Candidates. Cells 2022, 11, 653, 10.3390/cells11040653.

- Heinzerling, L.; Mari, A.; Bergmann, K.C.; Bresciani, M.; Burbach, G.; Darsow, U.; Durham, S.; Fokkens, W.; Gjomarkaj, M.; Haahtela, T.; et al. The skin prick test—European standards. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2013, 3, 3.

- Jakob, T.; Rafei-Shamsabadi, D.; Spillner, E.; Müller, S. Diagnostics in Hymenoptera venom allergy: Current concepts and developments with special focus on molecular allergy diagnostics. Allergo J. Int. 2017, 26, 93–105.

- Oppenheimer, J.; Durham, S.; Nelson, H.; Wolthers, O.D. World Allergy Organization Website. Allergy Diagnostic Testing. Available online: https://www.worldallergy.org/education-and-programs/education/allergic-disease-resource-center/professionals/allergy-diagnostic-testing (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Ansotegui, I.J.; Melioli, G.; Canonica, G.W.; Caraballo, L.; Villa, E.; Ebisawa, M.; Passalacqua, G.; Savi, E.; Ebo, D.; Gómez, R.M.; et al. IgE allergy diagnostics and other relevant tests in allergy, a World Allergy Organization position paper. World Allergy Organ. J. 2020, 13, 100080, Erratum in 2021, 14, 100557.

- Pitsios, C. Allergen Immunotherapy: Biomarkers and Clinical Outcome Measures. J. Asthma Allergy 2021, 14, 141–148.

- Matricardi, P.M.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; Hoffmann, H.J.; Valenta, R.; Hilger, C.; Hofmaier, S.; Aalberse, R.C.; Agache, I.; Asero, R.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; et al. EAACI Molecular Allergology User’s Guide. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27 (Suppl. 2), 1–250.

- Matricardi, P.M.; Dramburg, S.; Potapova, E.; Skevaki, C.; Renz, H. Molecular diagnosis for allergen immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 831–843.

- Bonadonna, P.; Bonifacio, M.; Lombardo, C.; Zanotti, R. Hymenoptera Allergy and Mast Cell Activation Syndromes. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015, 16, 5.

- Van Anrooij, B.; van der Veer, E.; de Monchy, J.G.R.; van der Heide, S.; Kluin-Nelemans, J.C.; Van Voorst Vader, P.C.; van Doormaal, J.J.; Oude Elberink, J.N.G. Higher mast cell load decreases the risk of Hymenoptera venom–induced anaphylaxis in patients with mastocytosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 125–130.

- Valent, P.; Horny, H.P.; Li, C.Y.; Longley, J.B.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Parwaresch, R.M.; Bennett, J.M. Mastocytosis (Mast Cell Disease), 4th ed.; Swerdlow, S.H., Campo, E., Harris, N.L., Jaffe, E.S., Pileri, S.A., Stein, H., Thiele, J., Vardiman, J.W., Eds.; World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours; Pathology & Genetics; Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2008; pp. 54–63.

- Korosec, P.; Erzen, R.; Silar, M.; Bajrovic, N.; Kopac, P.; Kosnik, M. Basophil responsiveness in patients with insect sting allergies and negative venom-specific immunoglobulin E and skin prick test results. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2009, 39, 1730–1737.

- Bonadonna, P.; Zanotti, R.; Melioli, G.; Antonini, F.; Romano, I.; Lenzi, L.; Caruso, B.; Passalacqua, G. The role of basophil activation test in special populations with mastocytosis and reactions to hymenoptera sting. Allergy 2012, 67, 962–965.

- George-Gay, B.; Parker, K. Understanding the complete blood count with differential. J. PeriAnesth. Nurs. 2003, 18, 96–117.

- Roufosse, F.; Weller, P.F. Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 39–44.

- Williams, K.W.; Milner, J.D.; Freeman, A.F. Eosinophilia Associated with Disorders of Immune Deficiency or Immune Dysregulation. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2015, 35, 523–544.

- Miehlke, S.; Alpan, O.; Schröder, S.; Straumann, A. Induction of Eosinophilic Esophagitis by Sublingual Pollen Immunotherapy. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2013, 7, 363–368.

- Iragorri, N.; Spackman, E. Assessing the value of screening tools: Reviewing the challenges and opportunities of cost-effectiveness analysis. Public Heal. Rev. 2018, 39, 17.

- Lin, E.C. Radiation Risk From Medical Imaging. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 1142–1146.

- Pitsios, C.; Demoly, P.; Bilò, M.B.; Van Wijk, R.G.; Pfaar, O.; Sturm, G.J.; del Rio, P.R.; Tsoumani, M.; Gawlik, R.; Paraskevopoulos, G.; et al. Clinical contraindications to allergen immunotherapy: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2015, 70, 897–909.

More