Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Mohammad Almasri and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common type of leukemia in adults, is characterized by a high degree of clinical heterogeneity that is influenced by the disease’s molecular complexity. The genes most frequently affected in CLL cluster into specific biological pathways, including B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, apoptosis, NF-κB, and NOTCH1 signaling. BCR signaling and the apoptosis pathway have been exploited to design targeted medicines for CLL therapy.

- chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- precision medicine

1. Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common type of leukemia in adults. The median age at diagnosis is 72 years, and the male to female ratio is 1.7:1. CLL is characterized by the monoclonal expansion of mature B cells with typical phenotype (CD5+ CD19+ CD20+ CD23+ sIg low) in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissues. The development of CLL is often preceded by a non-symptomatic precursor state called monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), defined as a monoclonal B-cell count <5 × 109/L with the typical phenotype of CLL [1].

CLL is characterized by a marked degree of heterogeneity both at the clinical and at the biological level. Some patients have an indolent disease that does not require therapy for many years. Conversely, other patients have an aggressive disease that requires treatment soon after diagnosis and/or may subsequently undergo histologic transformation into an aggressive lymphoma, known as Richter syndrome [2]. The biological heterogeneity of CLL can be ascribed to the immunogenetic origin of the disease, as reflected by immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IGHV) gene status as well as to the profile of genetic alterations of proto-oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes that are acquired by each individual patient [2][3][4][2,3,4].

The mutational status of IGHV genes plays a pivotal role in the biological and clinical profile of CLL. Mutated CLL (M-CLL) displays a rate of somatic hypermutation in the IGHV genes higher than 2% when compared to the corresponding germline IGHV gene counterpart, derived from post-germinal center (GC) B cells, and generally has an indolent disease course [5]. Conversely, unmutated CLL (U-CLL) displays a rate of IGHV gene somatic hypermutation lower than 2% compared to the corresponding germline IGHV gene counterpart, does not experience the GC reaction, and displays a more aggressive disease course [6][7][6,7]. B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling plays a fundamental pathogenic role in CLL, as documented by the biased usage of IGHV genes as well as by evidence of the dependence of CLL cell survival and growth upon BCR signaling [8][9][8,9]. These notions point to the BCR as a key component in CLL development and progression and as a main druggable pathway for molecular therapy with BCR inhibitors [8].

In addition to the BCR pathway, several molecular studies have identified different genetic lesions that might be used as molecular predictors or therapeutic targets [3][4][10][3,4,10]. The genetic landscape of CLL lacks a unifying molecular alteration, is markedly heterogeneous, and includes gross chromosomal aberrations, namely del13q14, trisomy 12, del17p13, and de11q23 as well as mutations of many cancer-related genes. The genes most frequently affected by molecular alterations in CLL cluster into specific biological pathways, including NOTCH1 signaling (NOTCH1 and FBXW7), DNA damage response (ATM, TP53, POT1), apoptosis (miR15/16 and BCL2), BCR and toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (EGR2, BCOR, MYD88, TLR2, IKZF3), NF-κB signaling (BIRC3, NFKBIE, TRAF2, TRAF3), and RNA splicing and metabolism (SF3B1, U1, XPO1, DDX3X, RPS15) (Table 1) [9][11][12][9,11,12].

Table 1. Main molecular pathways involved by gene mutations in CLL.

| The Biological Pathways | Mutated Genes |

|---|---|

| NOTCH1 Signaling | NOTCH1, FBXW7 |

| BCR and Toll-like receptor signaling | EGR2, BCOR, MYD88, TLR2, IKZF3 |

| MAPK-ERK pathway | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, MAP2K1 |

| RNA Splicing and metabolism | SF3B1, U1, XPO1, DDX3X, RPS15 |

| NF-κB Signaling | BIRC3, NFKBIE, TRAF2, TRAF3 |

| DNA damage response | ATM, TP53, POT1 |

| Apoptosis | miR15/16, BCL2 |

The continuous improvement in the understanding of CLL pathogenesis has allowed the development of novel therapies that specifically target pivotal signaling pathways of CLL cells. TIn the researcherspresent review, we cover the main biological pathways of CLL pathogenesis and the potential vulnerabilities that might be targeted in each pathway. Targeted therapy has already entered the clinical practice of CLL since several years, and its role is continuously expanding. In fact, seminal translational studies have led to understand that CLL genetic features (i.e., IGHV mutational status and TP53 abnormalities) are important biomarkers of refractoriness to chemotherapy and, therefore, act as predictors for treatment choices [2][4][13][14][2,4,13,14]. For example, TP53 disruption and unmutated status of IGHV genes are well-established predictors of chemorefractoriness that mandate treatment with targeted agents (BCR and/or BCL2 inhibitors) that can circumvent, at least in part, the CLL refractoriness to chemo-immunotherapy (CIT). In addition, other gene mutations (i.e., NOTCH1, BIRC3) are under scrutiny in order to clearly define their prognostic and/or predictive value [3][10][15][16][17][3,10,15,16,17].

2. Targeting the BCR in CLL

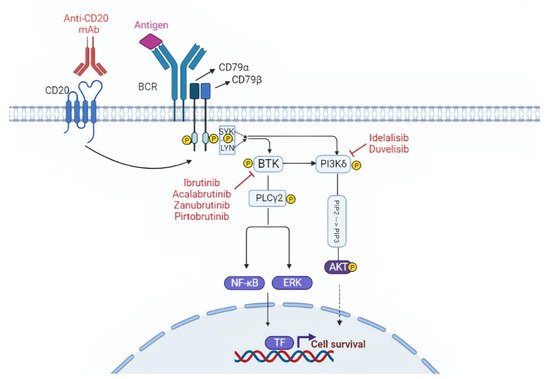

The BCR consists of a membrane immunoglobulin non-covalently bound to a heterodimer composed of CD79α (Igα) and CD79β (Igβ). In normal B cells, antigen binding to the BCR triggers the downstream signaling cascade, thus inducing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation stimuli (Figure 1) [18][19][18,19]. Compared to normal B cells, the BCR of many CLL cells is characterized by an intrinsically higher reactivity to antigens [20][21][20,21]. Moreover, in some cases, the BCR of CLL cells may also interact with a BCR expressed on other CLL cells, thus auto-enhancing BCR signaling [21][22][21,22]. About one-third of patients with CLL carry quasi-identical BCR sequences that can be classified into stereotyped BCR subsets based on the structure of their complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) [23][24][23,24]. Approximately 200 different CLL stereotyped BCR subsets have been identified to date [23]. These findings reinforce the notion that specific antigenic stimuli triggering the BCR may be involved in CLL pathogenesis.

Figure 1. Targeting the B cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway. The BCR is constituted of a membrane immunoglobulin attached to the CD79a/CD79b complex. The antigen binding leads to the interaction between the ITAM domain of CD79a/CD79b and the Syk and Lyn kinases. This interaction triggers the downstream BCR signaling cascade. BTK and PI3K play a pivotal role in the BCR cascade and drugs that inhibit these two molecules are represented in the figure. TF, transcription factors.

The BCR is connected to a network of kinases and phosphatases that regulate and amplify its activation. Upon antigen binding, the BCR initiates a signaling cascade through the phosphorylation of Igα (CD79α) and Igβ (CD79β) by Lyn and other Src family kinases. These events are followed by the activation of other kinases, namely SYK, Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), and phosphoinositide-3 kinases (PI3Ks), which will transmit the signal to downstream pathways important for B-cell growth and survival, including AKT, ERK, and NF-κB (Figure 1) [19].

As stated above, BCR signaling is essential for CLL pathogenesis and proliferation and can be targeted in vivo by inhibiting the BTK that plays a pivotal role in the BCR cascade. Different BTK inhibitors (BTKi) with different modes of action are currently used or are in development in advanced stage clinical trials. In addition to BTK, PI3K is also a druggable target in CLL.

2.1. BTK Inhibitors

BTK is a crucial intracellular protein downstream of the BCR, whose expression is upregulated in CLL cells [25]. BTKi are small, orally available molecules that bind to the Cys481 residue near to the ATP-binding domain of the BTK protein by covalent or non-covalent bonds. This active occupancy of the ATP binding domain inhibits the subsequent phosphorylation of BTK and blocks the downstream signaling pathways, including AKT and NF-kB, which regulate cell survival and proliferation. BTKi can be grouped into covalent BTKi (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib) and non-covalent BTKi (pirtobrutinib) [26][27][26,27].

CLL patients may develop resistance against BTKi by different mechanisms, including mutations of the BTK binding site and of the gene encoding phospholipase C Gamma 2 (PLCG2), which acts downstream of BTK in the BCR signaling cascade. BTK mutations are represented by substitutions of the Cys481 residue with a different amino acid, leading to the loss of the bond between the drug and the kinase. PLCG2 alterations are gain of function mutations, which can activate downstream BCR signaling independent of BTK inhibition. Both BTK mutations and PLCG2 mutations lead to loss of the activity of the BTKi [25][28][29][25,28,29].

2.1.1. Ibrutinib

Ibrutinib, the first-in-class covalent BTKi, has significantly changed the natural history and the management of CLL patients [25]. Ibrutinib can induce off-target effects by inhibiting other kinases that have a corresponding cysteine residue in the ATP binding site similar to BTK, such as epidermal-derived growth factor receptor (EGFR) family kinases, TEC family proteins, and interleukin-2-inducible tyrosine kinase (ITK). These off- target inhibition cause undesired side effects, which might limit the treatment, such as atrial fibrillation (AF) and bleeding [30][31][30,31].

Long-term outcomes of pivotal early phase studies have demonstrated durable responses with progression-free survival (PFS) rates that at 7 years exceed 80% in treatment-naïve patients [32]. Importantly, these reports highlight that ibrutinib is highly active also in TP53-disrupted patients, in which the drug allows to achieve a 6-year PFS and overall survival (OS) of 61% and 79%, respectively [33]. Subsequent phase 3 trials of ibrutinib single agent or in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) have shown that the drug significantly prolongs outcomes of both young and fit CLL patients and elderly patients with comorbidities compared to CIT regimens [34][35][36][34,35,36]. Interestingly, ibrutinib completely overcomes the negative prognostic impact of unmutated IGHV genes, and since its mode of action is independent of TP53, it also smoothens the detrimental impact of TP53 disruption in CLL cells [37] (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical trials in CLL.

| Trial | Phase | Setting | Interventions | N. of Patients | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibrutinib-Rituximab or Chemoimmunotherapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia [34] | 3 | Untreated patients with CLL or SLL subtype of CLL | Ibrutinib-Rituximab | 354 | 3 years: 89.4% | 3 years: 98.8% |

| Chemoimmunotherapy (FCR) | 175 | 3 years: 72.9% | 3 years: 91.5% | |||

| Venetoclax and Obinutuzumab in Patients with CLL and Coexisting Conditions [38] | 3 | Untreated patients with CLL | Venetoclax + Obinutuzumab | 216 | 24 months: 88.2% | 24 months: 91.8% |

| Chlorambucil + Obinutuzumab | 216 | 24 months: 64.1% | 24 months: 93.3% | |||

| Ibrutinib Regimens versus Chemoimmunotherapy in Older Patients with Untreated CLL [36] | 3 | Untreated patients with CLL aged ≥65 | Bendamustine + Rituximab | 183 | 24 months: 74% | 24 months: 95% |

| Ibrutinib | 182 | 24 months: 87% | 24 months: 90% | |||

| Ibrutinib + Rituximab | 182 | 24 months: 88% | 24 months: 94% | |||

| Ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (iLLUMINATE): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial [39] | 3 | Untreated patients with CLL or SLL either aged 65 years or older or younger than 65 years with coexisting conditions | Ibrutinib + Obinutuzumab | 113 | Median PFS: not reached (Estimated) 30 months: 79% |

Median OS: not reached (Estimated) 30 months: 86% |

| Chlorambucil + Obinutuzumab | 116 | Median PFS: 19 months (Estimated) 30 months: 31% |

Median OS: not reached at (Estimated) 30 months: 85% |

|||

| Long-term follow-up of the RESONATE phase 3 trial of Ibrutinib vs. Ofatumumab [37] |

3 | Previously treated patients with CLL or SLL requiring a new therapy and not eligible for purine analog-based therapy | Ibrutinib | 195 | Median PFS: not reached 3 years: 59% |

Median OS: not reached 3 years: 74% |

| Ofatumumab [Note: 68% of patients in this arm crossing over to ibrutinib] |

196 | Median PFS: 8.1 months 3 years: 3% |

Median OS: not reached 3 years: 65% |

|||

| Venetoclax-Rituximab in Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia [40] | 3 | Patients aged 18 years or older with relapsed or refractory CLL | Venetoclax + Rituximab | 194 | 2 years overall: 84.9% | 2 years overall: 91.9% |

| Bendamustine + Rituximab | 195 | 2 years overall: 36.3% | 2 years overall: 86.6% | |||

| Acalabrutinib Versus Ibrutinib in Previously Treated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Results of the First Randomized Phase III Trial [41] |

3 | Patients with previously treated CLL with centrally confirmed del(17)(p13.1) or del(11)(q22.3) | Ibrutinib | 265 | Median PFS: 34.8 months | Median OS: not reached 3 years: >60% |

| Acalabrutinib | 268 | Median PFS: 34.8 months | Median OS: not reached 3 years: >60% |

|||

| Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and Obinutuzumab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE TN): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial [42] | 3 | Untreated patients with CLL ged 65 years or older, or older than 18 years and younger than 65 years with creatinine clearance of 30–69 mL/min or Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics score greater than 6. | Acalabrutinib | 179 | Median PFS not reached | Median OS: not reached 3 years: >80% |

| Acalabrutinib + Obinutuzumab | 179 | Median PFS not reached | Median OS: not reached 3 years: >80% |

|||

| Chlorambucil + Obinutuzumab | 177 | Median PFS: 22.6 months | Median OS: not reached 3 years: >80% |

|||

| The phase 3 DUO trial: duvelisib vs. ofatumumab in relapsed and refractory CLL/SLL | 3 | Relapsed or refractory CLL/SLL [43] | Duvelisib | 160 | Median PFS: 13.3 months | Median OS: not reached 3 years: >50% |

| Ofatumumab | 159 | Median PFS: 9.9 months | Median OS: not reached 3 years: >50% |

2.1.2. Acalabrutinib

Acalabrutinib is a more potent and selective inhibitor of BTK in comparison to ibrutinib, and given the lower activity of the drug against other kinases (e.g., ITK, EGFR, ERBB2), it is less likely to cause off-target adverse events [44][45][44,45]. Acalabrutinib has demonstrated superior PFS compared to CIT or to the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib in a phase 3 study dedicated to relapsed/refractory (R/R) patients (ASCEND trial) [46]. Furthermore, acalabrutinib single agent or in combination with the anti-CD20 mAb Obinutuzumab has been shown to prolong PFS in first-line setting in elderly CLL patients with comorbidities (ELEVATE-TN trial) [42]. Because of its higher affinity for BTK, acalabrutinib has also demonstrated high efficacy and tolerability in ibrutinib-intolerant patients with CLL [47][48][47,48].

Recently, a head-to-head comparison of ibrutinib versus acalabrutinib has been carried out in a phase 3 trial dedicated to R/R CLL patients (ELEVATE-RR). This trial has demonstrated the non-inferiority of acalabrutinib compared to ibrutinib in terms of PFS and has documented that acalabrutinib associates with an improved safety profile with fewer AF events and discontinuations because of adverse events [41] (Table 2).

2.1.3. Zanubrutinib

Zanubrutinib is a next-generation BTKi with favorable oral bioavailability and high specificity for BTK, exhibiting lower off-target activity than ibrutinib for structurally related kinases, such as EGFR and ITK [49]. Phase 2 studies in both the treatment naïve (TN) and R/R CLL with TP53 disruption have shown an overall response rate (ORR) of more than 85% [50][51][52][50,51,52]. Recently, an interim analysis of a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial comparing ibrutinib versus zanubrutinib in R/R CLL patients has demonstrated that zanubrutinib has a superior response rate, an improved PFS, and a lower rate of atrial fibrillation/flutter compared to ibrutinib [53].

2.1.4. Pirtobrutinib

The most common mechanisms of resistance to covalent BTKi include mutations at the binding site of the drugs (BTK Cys481) and gain-of-function mutations of the downstream PLCγ2 phospholipase [54][55][54,55]. Pirtobrutinib is an orally available, highly selective, reversible BTKi with equal low nM potency against both wild-type and Cys481-mutated BTK [56]. In a phase 1/2 study of pirtobrutinib in B-cell malignances, the ORR of R/R CLL patients to pirtobutinib was 62% [57]. The ORR was similar in CLL patients who had been exposed and become resistant to covalent BTKi, had developed intolerance to covalent BTKi, had acquired a Cys481 mutation in the BTK gene, or had a BTK wild-type disease [57]. In terms of side effects, pirtobrutinib demonstrated a good safety profile. In fact, grade 3 AF or flutter was not observed, and only 1% of patients discontinued treatment due to a therapy-related adverse event [57].

2.2. PI3K Inhibitors

PI3Ks are a family of enzymes involved in cellular functions, such as cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, and survival, and are frequently dysregulated in cancers. PI3K are subdivided into three classes, termed as class I, II, and III. Class I PI3Ks comprise four isoforms, namely PI3K-α, -β, -γ, and -δ. The PI3Kδ isoform is a kinase that amplifies and transduces signals from the BCR on the cell surface to the downstream AKT signaling pathway and is the most relevant target in CLL [12][58][12,58]. PI3Ki are small, orally available molecules that bind the ATP binding pocket of the PI3K. As a consequence, a major survival signaling pathway in CLL cells, involving AKT, will be inhibited [58]. In addition to PI3Ks inhibitors, this pathway can also be inhibited by the AKT o mTOR inhibitors that are in development [59].

PI3Ki molecules have various specificities and affinities to bind the different PI3K isoforms. One of the major challenges in the development of PI3Ki is the inability to achieve an optimal molecule that can target a specific isoform. The toxicities from these small-molecules depend on their degree of PI3K isoform specificity [60]. As previously described, different PI3K isoforms are present in human cells, and the isoform δ is a suitable target in CLL cells [61]. Two PI3Ki have been tested in advanced stage clinical trials, namely idelalisib and duvelisib.

2.2.1. Idelalisib

Idelalisib is the first commercially approved PI3Kδ inhibitor for patients with CLL. This molecule demonstrated meaningful clinical activities in R/R patients in the context of phase 2 clinical trials [62]. The phase 3 trial compared idelalisib-rituximab with placebo-rituximab in R/R CLL [63][64][63,64]. Idelalisib-rituximab resulted in superior PFS (not reached vs. 5.5 months) and OS at 12 months (92% vs. 80%) [63][64][63,64]. Patients with high-risk disease features, such as TP53 aberrations or IGHV unmutated status, had similar PFS to those without such features [63][64][63,64]. Adverse events included neutropenia (65%), transaminitis (39%), and diarrhea or colitis in 36% of patients. Opportunistic P jirovecii infections were seen in patients who had not received prophylaxis [63][64][63,64].

2.2.2. Duvelisib

The efficacy of idelalisib encouraged development of other PI3Ki. Duvelisib is an oral dual inhibitor of PI3Kd and PI3Kg that is uniquely positioned to target both intracellular and extracellular survival signals [65]. Considering all tested dose levels, adverse events were similar to those reported for idelalisib, with neutropenia (39%), increased transaminase levels (39%), and diarrhea (42%). Early efficacy data in CLL were promising, with a 56% ORR and a median PFS of 15.7 months across all dose levels [66]. The subsequent phase 3 trial tested duvelisib versus ofatumumab (an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) in R/R CLL. The median PFS was superior for duvelisib versus ofatumumab (17.6 months versus 9.7 months) [43]. As with idelalisib, PFS was similar in TP53-aberrant and TP53-intact disease [43]. Adverse events were similar to those reported in earlier phase trials, and cases of P jirovecii pneumonia were restricted only to subjects not receiving anti-infectious prophylaxis [43][67][43,67] (Table 2).