Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Nora Tang and Version 1 by Antonio Peña-García.

Nuclear facilities are a main milestone in the long way to sustainable energy. Beyond the well-known fission centrals, the necessity of cleaner, more efficient and almost unlimited energy reducing waste to almost zero is a major challenge in the next decades. This is the case with nuclear fusion. Different experimental installations to definitively control this nuclear power are proliferating in different countries. However, citizens in the surroundings of cities and villages where these installations are going to be settled are frequently reluctant because of doubts about the expected benefits and the potential hazards.

- sustainable development

- psychosocial risks

- socioeconomic impact

- nuclear facilities

1

1. Introduction

A lot of attention has been paid to energy sources that can contribute to Sustainable Development from all perspectives, as defined in the Brundtland Report, that is, the “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [1]. Among these needs, clean energy allowing industrial production, transport and other is essential [2].

Although the concerns related to clean energy itself are clear and well established (environmental protection, well use of resources and raw materials, economic savings etc.), it is not so clear how the pursuit of clean energy can affect people.

In this sense, nuclear power is a matter of concern whose classification as a “green energy source” is currently under consideration by the European Commission. This body bases its arguments on the Joint Research Center (JCR) report on Technical assessment of nuclear energy with respect to the “do no significant harm” criteria of Regulation (EU) 2020/852 [3]. Beyond these considerations, nuclear fusion is expected to overcome the main disadvantages of the currently used nuclear fission, especially in matters of waste management and the availability of Uranium and Plutonium.

However, the path towards the control of nuclear fusion is a paradigm of extremely complex research and very expensive experimental infrastructures like the “International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor” (ITER), the world’s largest fusion experiment whose target is proving the feasibility of fusion as a large-scale and carbon-free source of energy [4], and the “International Fusion Materials Irradiation Facility—Demo Oriented NEutron Source” (IFMIF-DONES) [5].

In this framework, it is essential to investigate how these large experimental infrastructures will impact on their surroundings from all the possible perspectives: social, economic, cultural and many others [5][6].

In addition, a successful implementation of nuclear experimental facilities like ITER and IFMIF-DONES (the target of this work) in their geographical and socioeconomic context does not depend only on the objective abovementioned factors; it is also important to make sure that people living and working around will feel safe and free of uncertainties that could impact their health and well-being. If that were the case, infrastructures like those would not foster, but impair Sustainable Development due to massive migration, abandonment of the activities and main services in the zone, etc. [7].

2. The International Fusion Materials Irradiation Facility—Demo-Oriented NEutron Source (IFMIF-DONES)

The need for more and more energy to ensure economic growth and resources for everyone without harming the environment makes both the scientific community and governments around the world work hard to control nuclear fusion and thus profit from its huge benefits.

Although there are large international experiments running or near to starting to work [1][2], serious technical problems in the long way towards the control of fusion energy still remain. In addition to the control of plasmas at about 150 MK, the control of the produced neutrons that cannot be stopped with magnetic fields is one of the main problems.

The aim of IFMIF-DONES is to obtain neutrons like those to be produced in real fusion reactions and irradiate different materials in order to know which one or ones are the most suitable for the construction of the future fusion reactors [3][4]. This project has been acknowledged as critical in the path towards the control of nuclear fusion for years; it was definitively legislated and its objectives, scope, limits and finality, defined in the Broader Approach between the European Atomic Energy Community (EUROATOM) and the Government of Japan [5].

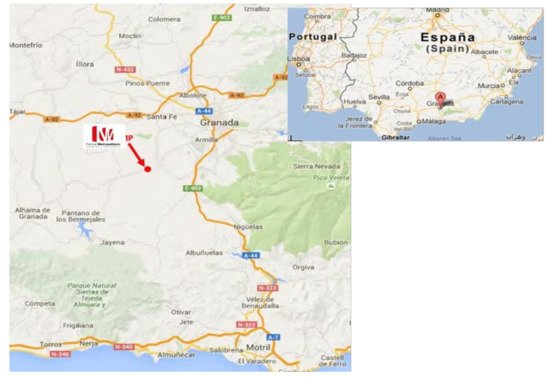

This unique experimental scientific facility has started to be built in Escúzar (Province of Granada, South of Spain) (Figure 1). The initial budget of the Project is about 700 M€ that will be mainly funded by the European Regional Development Fund [6], EUROfusion [7] and other European programs, as well as national funds from other programs [8]. In spite of the typical challenges to set up such complex scientific infrastructure (project management, funds acquisition, construction, future maintenance etc.), its interaction with people living and working near its location is a major concern. Indeed, it is not enough that the neighbors will enjoy better infrastructures and a higher level of incomes: they must also feel comfortable with the infrastructure itself and the changes that it will bring to their traditional way of life.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of IFMIF-DONES (Escúzar-Granada, Spain).

Among these circumstances, the perceived risks coming from IFMIF-DONES is one of the most important since a negative perception could even lead people to leave the area, which would cause the opposite effect than is intended and consequences for the Sustainable Development of the zone.

In the next item, some basic concepts about psychosocial perceived risks will be presented in order to introduce one of the main novelties of this work.

23. Perceived Psychosocial Hazards

The concept of “psychosocial hazards” refers to aspects relating our social environment and their consequences on our health and wellbeing. It is generally associated to the labour environment, mainly focused on the negative interrelationship between working conditions and the human factors [9].

Some of the first documents approaching psychosocial hazards in depth came from the International Labour Organization (ILO) [10], which in 1984, together with the World Health Organization (WHO) defined them as “the interactions between and among work environment, job content, organizational conditions and workers’ capacities, needs, culture, personal extra-job considerations that may, through perceptions and experience, influence health, work performance and job satisfaction” [11]. Later, it was explained how each factor impacts the workers in a different way according to their individual perception.

In parallel, the shift from the agricultural and industrial sectors to the production of services and other new activities narrowly linked to the wide concept of Sustainable Development [12] is the basis for new psychosocial risks, real and perceived. These are the aim of this research.

In this context, it is important to distinguish between safety (or hazard) and perceived safety (or hazard). Evaluating the perception of safety and potential psychosocial hazards among the people living or working near critical installations such as factories, power plants, experimental facilities and others, is a key factor to prevent the negative impacts of these installations on people’s physical and mental health.

The evaluation of perceived safety in streets and other civil infrastructures [13][14][15][16], and also in nuclear plants producing energy from fission [17][18][19][20][21][22], are fields of active research, widely approached in the literature, whilst the perceived psychosocial hazards in experimental facilities devoted to testing new ways of energy production are scarcely studied. The choice of a survey for their evaluation is a feasible and useful tool that allows people to express their opinion so that Public Administrations can plan special projects without negative impact on people living in the surroundings.

References

- International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) website. Available online: https://www.iter.org/ (accessed on 21 October 2021).World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Joint European Torus (JET) Website. Available online: https://www.euro-fusion.org/devices/jet/ (accessed on 21 October 2021).Lund, H. Renewable energy strategies for sustainable development. Energy 2007, 32, 912–919.

- IFMIF-DONES website. Available online: https://ifmifdones.org (accessed on 21 October 2021).Abousahl, S.; Carbol, P.; Farrar, B.; Gerbelova, H.; Konings, R.; Lubomirova, K.; Martin Ramos, M.; Matuzas, V.; Nilsson, K.; Peerani, P. Technical Assessment of Nuclear Energy with Respect to the ‘Do No Significant Harm’ Criteria of Regulation (EU) 2020/852 (‘Taxonomy Regulation’); EUR 30777 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 9789276405382.

- Królas, W.; Ibarra, A.; Arbeiter, F.; Bernardi, D.; Cappelli, M.; Castellanos, J.; Dezsi, T.; Dzitko, H.; Favuzza, P.; Garcia, A.; et al. The IFMIF-DONES fusion oriented neutron source: Evolution of the design. Nuclear Fusion 2021, 61, 125002. International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) website. Available online: https://www.iter.org/ (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- European Union. Agreement between the European Atomic Energy Community and the Government of Japan for the Joint Implementation of the Broader Approach Activities in the Field of Fusion Energy Research. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22007A0921(01)&from=EN (accessed on 3 December 2021).Fernández-Pérez, V.; Peña-García, A. The Contribution of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures to Sustainable Development from a Global and Territorial Perspective: The Case of IFMIF-DONES. Sustainability 2021, 13, 454.

- European Commission website/European Regional Development Fund. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/funding/erdf (accessed on 21 October 2021).Esteban-López, R.; Troya, Z.; Fernández-Pérez, V.; Peña-García, A. The contribution of experimental energy facilities to the achievement of SDG in their environment: The case of IFMIF-DONES. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ’21), Almeria, Spain, 28–30 July 2021.

- EUROfusion website. Available online: https://www.euro-fusion.org (accessed on 21 October 2021).Nguyen, T.P.L.; Peña-García, A. Users’ Awareness, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Health Risks Associated with Excessive Lighting in Night Markets: Policy Implications for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6091.

- Esteban, R.; Troya, Z.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Peña-García, A. IFMIF-DONES as paradigm of institutional funding in the way towards sustainable energy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13093.

- International Labour Office (ILO). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- International Labour Office (ILO). Psychosocial Factors at Work: Recognition and Control; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 1984; Available online: https://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/ILO_WHO_1984_report_of_the_joint_committee.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Kalimo, R.; El Batawi, M.A.; Cooper, C.L. Psychosocial Factors at Work and their Relation to Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1988.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Peña-García, A.; Hurtado, A.; Aguilar-Luzón, M.C. Impact of public lighting on pedestrians’ perception of safety and well-being. Saf. Sci. 2015, 78, 142–148.

- Peña-García, A.; Hurtado, A.; Aguilar-Luzón, M.C. Considerations about the impact of public lighting on pedestrians’ perception of safety and well-being. Saf. Sci. 2016, 89, 315–318.

- Peña-García, A.; Nguyen, T.P.L. A global perspective for sustainable highway tunnel lighting regulations: Greater road safety with a lower environmental impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2658.

- Qin, P.; Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Yan, G.; Yan, T.; Han, C.; Bao, Y.; Wang, X. Characteristics of driver fatigue and fatigue-relieving effect of special light belt in extra-long highway tunnel: A real-road driving study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 114, 103990.

- Slovic, P.; Flynn, J.H.; Layman, M. Perceived risk, trust, and the politics of nuclear waste. Science 1991, 254, 1603–1607.

- Slovic, P.; Layman, M.; Kraus, N.; Flynn, J.; Chalmers, J.; Gesell, G. Perceived Risk, Stigma, and Potential Economic Impacts of a High-Level Nuclear Waste Repository in Nevada. Risk Anal. 1991, 11, 683–696.

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Kunreuther, H.C. Chapter 11 Siting of hazardous facilities. Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science 1994, 6, 403–440.

- Grove-White, R.; Kearnes, M.; Macnaghten, P.; Wynne, B. Nuclear Futures: Assessing Public Attitudes to New Nuclear Power. Political Q. 2006, 77, 238–246.

- Chilvers, J.; Burgess, J. Power Relations: The Politics of Risk and Procedure in Nuclear Waste Governance. Environ. Plan. A: Econ. Space 2008, 40, 1881–1900.

- Pidgeon, N.F.; Lorenzoni, I.; Poortinga, W. Climate change or nuclear power—no thanks! A quantitative study of public perceptions and risk framing in Britain. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 69–85.

More