Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Fabio Gelsomino and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

Small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA) is a rare malignancy, with a rising incidence in recent decades, and accounts for roughly 40% of all cancers of the small bowel. The majority of SBAs arise in the duodenum and are associated with a dismal prognosis. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for localized disease, while systemic treatments parallel those used in colorectal cancer (CRC), both in the adjuvant and palliative setting. In fact, owing to the lack of prospective data supporting its optimal management, SBA has historically been treated in the same way as CRC.

- small bowel

- precision oncology

- genomic profiling

1. Epidemiology

Small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA) accounts for less than 5% of gastrointestinal cancers [1][2]. Historically, it has been the dominant small intestinal histology, followed by neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma, and sarcoma (most commonly gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyosarcoma). In the following years, neuroendocrine tumors became the most frequent histology, especially in distal segments of the small intestine. The overall incidence of SBA is slowly increasing, with a mean age at diagnosis of 60 years and a prevalence in men [2][3]. The most involved segment is the duodenum (60%), followed by the jejunum (25–29%) and ileum (10–13%) [3][2][4][1,3,4]. The factors responsible for this different localization are not completely understood, but it has been supposed that the exposure to bile and its metabolites, due to the presence of the ampulla of Vater, might at least in part explain the differences [5].

2. Etiology

A number of risk factors and predisposing conditions has been described for SBA. Among lifestyle factors, alcohol consumption, smoking, and obesity are associated with an increased risk of this tumor [6]. Diet plays a relevant role, as a higher incidence of SBA has been found in consumers of carbohydrates, red meats, and lower intake of coffee, fruit, and vegetables [7]. Dietary risk factors are similar between SBA and CRC; nevertheless, the lower incidence SBA is probably caused by the short transit time in the small intestine with less contact with carcinogens. Chronic inflammation is correlated with the SBA etiology. Inflammatory bowel diseases, in particular Crohn disease, increase the incidence of SBA within the involved area of the small intestine. The risk augments with both the extent of the small bowel involvement and the duration of disease. Palascak-Juif et al. reported a cumulative risk of SBA of 2.2% after 25 years of Chron’s disease [8]. Patients who underwent small bowel resection have a lower risk of SBA [9]. Furthermore, patients affected by coeliac disease have a risk of developing an SBA of about 8% [10]. Other conditions associated with an increased risk of SBA are cystic fibrosis, as well as different hereditary cancer syndromes, such as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), Peutz-Jeghers, and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) [11][12][13][14][11,12,13,14].

3. Clinical Presentation and Initial Diagnostic Workup

Diagnosis of SBA is often insidious, because of the aspecific presentation. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain, weight loss, dyspepsia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, bloating, fatigue, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Sometimes, iron deficiency anemia from occult gastrointestinal bleeding may characterize the onset of the disease. SBA can lead to specific complications, depending on the tumor location, including jaundice, obstruction, and perforation. These symptoms can mimic other more common benign conditions, such as cholelithiasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or appendicitis, which can explain a mean symptom-to-diagnosis interval that can approach 2 years [15][21]. Furthermore, the limited sensitivity of conventional radiological imaging may significantly contribute to the delayed diagnosis [16][17][22,23]. Moreover, while a significant proportion of CRCs is screen-detected, the vast majority of SBAs presents with a local complication in an emergency situation, most often gastric outlet or biliary obstruction for duodenal tumors or cramping abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction for jejuno–ileal SBAs, which require specific management (i.e., palliative surgical diversion or endoscopic biliary stenting in patients with non-resectable disease, depending on tumor location). Therefore, it is not surprising that SBA presents with a more advanced disease as compared to CRC. Conventional endoscopy may be useful in the diagnosis of tumors of the proximal duodenum and very distal ileum. Other endoscopic techniques, such as wireless capsule endoscopy and double balloon endoscopy, can be useful in certain circumstances [18][19][24,25]. Wireless capsule endoscopy allows a complete small bowel exploration, but it is contraindicated in the context of an occlusion and does not allow a tissue biopsy, when deemed necessary [18][24]. Double balloon endoscopy may be useful in patients with small bowel strictures or when a biopsy or a preoperative tattoo is required [19][25]. Conventional imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) should be used for staging purpose. However, newer imaging techniques, such as CT or MR enterography or enteroclysis, can be taken into consideration after the failure of conventional imaging, if clinical suspicion persists [20][21][26,27].4. Future Perspectives

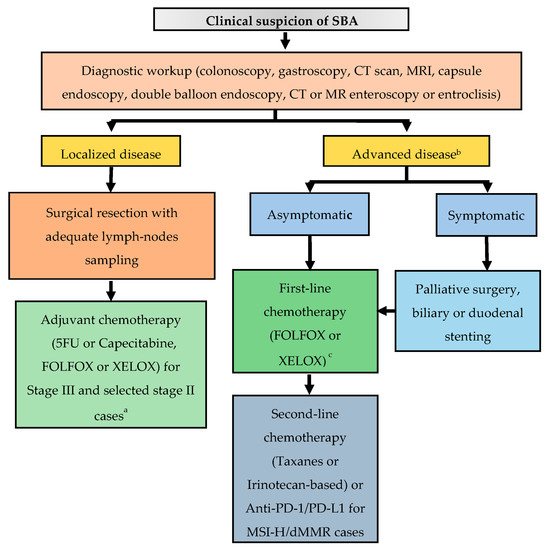

SBA is a rare malignancy, which, owing to its anatomic proximity to the large bowel, has historically been perceived to have a clinical behavior similar to CRC. However, aside its lower incidence and worse prognosis, comprehensive molecular profiling data speak in favor of its uniqueness. Owing to non-specific symptoms and the lack of screening programs, even in high-risk individuals, this disease is often diagnosed at an advanced stage. In patients with localized disease, surgical resection with adequate lymph node sampling represents the only treatment with a chance of cure. However, up to a third of patients with resectable disease experiences a relapse. Therefore, in particular for patients at higher risk of relapse, adjuvant chemotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine-based regimen is recommended, although definitive data on its efficacy are lacking. Enrollment in the BALLAD trial (NCT02502370), which will hopefully clarify the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in resected SBA, is strongly encouraged. Patients with stage IV disease are usually treated with systemic chemotherapy, which includes oxaliplatin-based doublets in the first-line setting and taxanes or irinotecan-based regimens in the second-line setting. Of note, a phase II, open-label, randomized trial is actually ongoing with the aim to compare the FOLFIRI regimen with paclitaxel plus ramucirumab in patients with pre-treated locally advanced or metastatic SBA (NCT04205968). Data about surgical resection of metastatic disease are extremely limited, and cases with potentially resectable oligometastatic disease should be discussed within experienced multidisciplinary teams. Recent in-depth genomic characterization of a large series of SBAs demonstrated its unique molecular profile as compared to neighboring GC and CRC [22][16]. Of note, potential targetable genomic alterations were identified in 91% of cases (including HER-2 amplifications/mutations, EGFR amplifications/mutations, MEK1 and BRAF mutations, and PI3K pathway activating alterations), thus suggesting further therapeutic options in an orphan disease of approved targeted agents. As genomic profiling techniques become more available in the near future, enrollment in clinical studies with innovative designs, especially basket trials, aiming at assessing the outcome of matched target therapies will be of paramount importance. On the other hand, developing new preclinical models to test potential therapeutic strategies will be equally crucial. Despite the great expectations after the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in the therapeutic armamentarium of various neoplasms, aside for MSI-H tumors, clinical trial results in the specific setting of SBA have been quite disappointing. However, in the work by Schrock and colleagues [22][16], a substantial proportion of MSS SBAs had a high TMB, a potential biomarkers of ICIs efficacy. Overall, the fraction of TMB-high SBAs was 9.5%, significantly higher than that of GC or CRC, thus suggesting further investigations on the role of ICIs in SBA. Figure 1 2 provides an algorithm for the management of patients with a clinical suspicion of SBA.

Figure 12. Suggested treatment algorithm in patients with a clinical suspicion of SBA. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; FOLFOX, 5-FU, oxaliplatin; XELOX, capecitabine, oxaliplatin; PD-1, programmed death-1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high; dMMR, deficient mismatch repair. a Chemo-radiotherapy for selected cases of duodenal tumors, after multidisciplinary discussion. b Genomic profiling for enrollment in clinical trials with matched target therapies is strongly encouraged. c Surgery of metastatic sites can be considered in selected cases with oligometastatic disease, after multidisciplinary discussion.