Multiple definitions of distributed leadership exist in the literature. For the purpose of clarity, researchers consider distributed leadership to involve the fostering of shared leadership practices which enhance school/workplace culture and practices. While differences may exist in terms of definitional concepts, there is clear consensus that context and setting are integral to the understanding of distributed leadership.

- distributed leadership

- school leadership

1. Introduction

Discussion of distributed leadership in the context of organisational theory can be traced back to the mid 1960′s [1]. However, the construct shares similar characteristics with that of decentralised administration such as the spreading of responsibility and decision-making, which has been in the literature since the late 1800′s [2]. It was not long before distributed leadership began to take a foothold in the field of education with academics, school policy makers and school leaders soon commencing considerations of the potential implications of adopting distributed leadership models in schools [3]. Distributed leadership has now become prevalent and pervasive in both policy and practice spheres [4]. Distributed leadership is currently the most frequently adopted school leadership theory internationally [5][6], and there has been a rapid increase in research on distributed leadership in schools in recent years [7].

1.2 Blurred Definitions of Distributed Leadership

Leadership is a relatively nebulous concept with various meanings in different contexts [8], and distributed leadership does not offer any more specific conceptual clarity than the general nomenclature of leadership per se [9]. Distributed leadership has become so conceptually vast that it is difficult to distinguish between what signifies the construct and what does not [10]. There is little consensus with regard to various interpretations of what distributed leadership is, or what it looks like in schools [11]. Diamond and Spillane [12] suggest that conflicting opinions emerge between individuals who view distributed leadership as an attractive model, and those who simply equate the construct to other forms of shared leadership. The variety of definitions of the concept has led to conceptual ambiguity and the overlapping of constructs blurring the meaning of the term [13], even though distributed leadership has been reported to be a relatively easy concept to understand [14]. While it is inevitable that there is some discrepancy in conceptualisations of distributed leadership [12], given the inconsistences in definitions of leadership itself, these inconsistently and weakly defined core constructs are problematic, and lead to fuzzy research [15].

2. Findings

2.1 Trend 1 Research Methods—Distributed Leadership Studies Used a Variety of Methodologies in Various Contexts

The majority of studies were carried out in the United States of America (30.8%, N = 12), followed by Belgium (20.5%, N = 8). The remaining studies were conducted in a number of countries in lesser frequency. The 39 studies included in the entry were either quantitative (35.9%, N = 14), mixed methods (33.3%, N = 13), or qualitative (30.8%, N = 12) in nature. The statistics show a relatively equal distribution of the different research designs. The most common research design chosen was a case study design with 33.3% (N = 13) of studies using this approach. The majority of studies included insights from both teachers and school leaders (61.5%, N = 24). Fewer numbers of studies chose a population of just teachers (20.5%, N = 8) or school leaders on their own (17.9%, N = 7).

2.2. Trend 2: Relationships—Distributed Leadership Studies were Related to Multiple Constructs

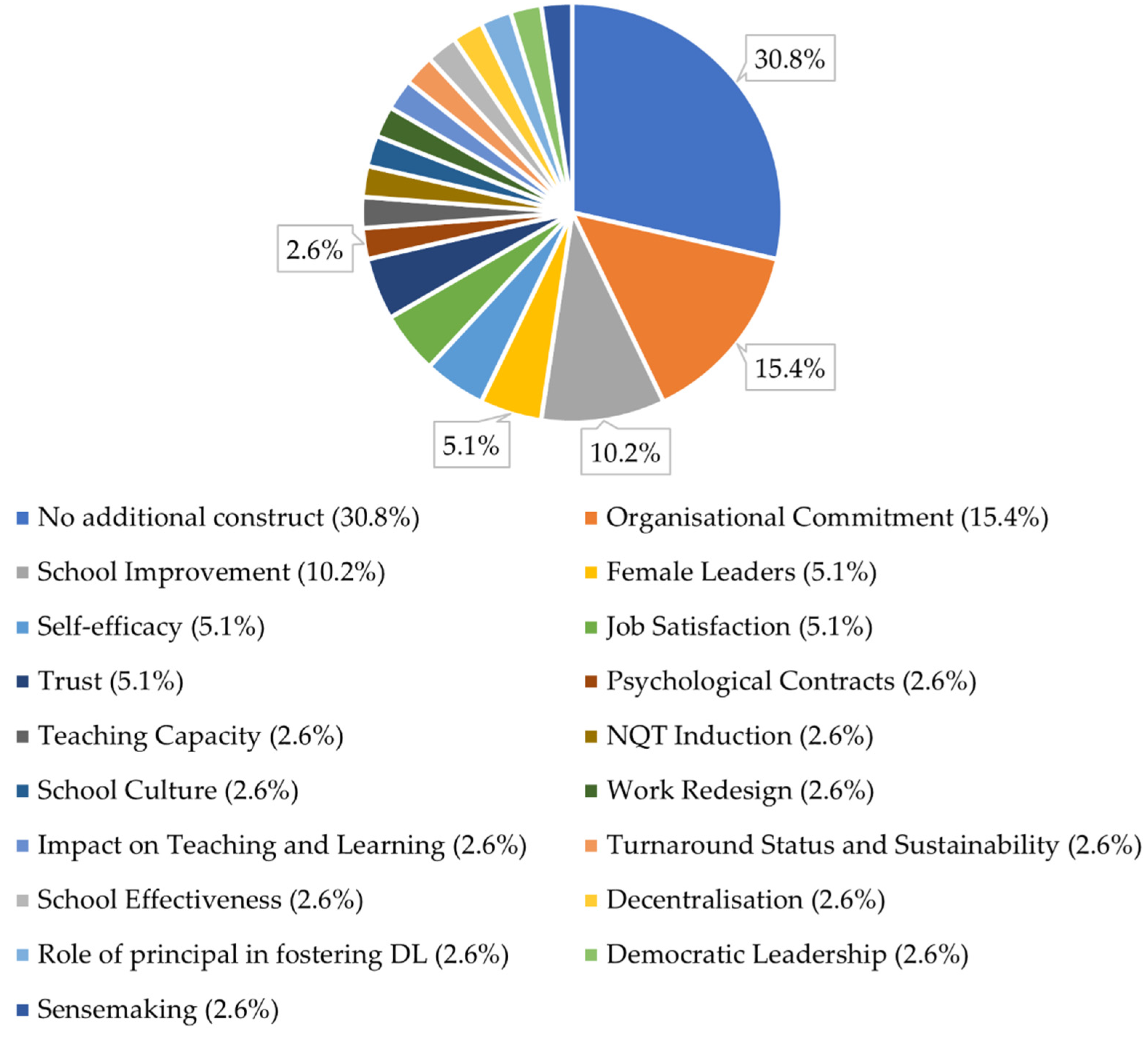

Many studies in this entry examined distributed leadership as the sole focus of the research (30.8%, N = 12). The remaining studies investigated distributed leadership in relation to another construct (69.2%, N = 27). These constructs are composed of theoretical frameworks, characteristics of leadership or features of a school which were studied alongside distributed leadership. The construct investigated most frequently alongside distributed leadership was found to be organisational commitment (15.4%, N = 6), followed by school improvement (10.2%, N = 4). Other constructs include female leadership, teaching capacity, job satisfaction etc. See Figure 1 for more details.

Figure 1: Construct studied in conjunction with distributed leadership

2.3. Trend 3: Conceptualisations Underpinning Studies—The Prevalence of Spillane’s Distributed Leadership Theory

Eighty two percent of studies reviewed (N = 32) were underpinned to some extent by the distributed leadership theoretical framework set out by Spillane [16]. This is to be expected as Spillane and his colleagues were heavily involved in developing the central conceptual model of distributed leadership [17]. Within these studies, distributed leadership is outlined as a set of functions that are carried out by a group of people rather than an individual.

2.4. Trend 4: Conceptualisations of Participants—Discrepancies in Participants’ Understandings of Distributed Leadership

Throughout the reviewed studies, it was common for research participants to have different perceptions of what distributed leadership is and how it may look in a particular setting. This ambiguity infers concern regarding the validity of research seeking to explore the influence of distributed leadership without due consideration being given to standardising perceptions, and understandings of the nature of the construct first. Nevertheless, it is noted that some ambiguity is to be expected given the elusiveness of the distributed leadership concept [1].

3. Implications

The findings of this entry can offer implications and directions for future research on distributed leadership in post-primary school settings. Researchers conclude from the findings that there is a need for greater rigour to be demonstrated in distributed leadership research. There is also a need for researchers to consider additional approaches to studying distributed leadership in post-primary schools

3.1. Rigour

3.1.1. Consideration of Policy and Context

The research methods used throughout the studies included in this entry vary considerably, but few studies have considered how the context in which the research took place could have influenced the findings of this research. For example, Hasanvand, et al. [18] outline the relationship between distributed leadership and principals’ self-efficacy in Iran. At this time distributed leadership had received little attention in Iran and leadership equated with authority and position [19]. In contrast to this, a study in this entry was conducted in South Africa [20] where the Policy for South African Standard for Principalship may not endorse distributed leadership per se but recommends empowering those in the school community and engaging in participative decision-making. It is reasonable to suggest that these policy contexts may influence adoption or lack thereof of leadership models. At the very least they are a contextual factor that warrant exploration. Leadership and organisational culture have a reciprocal dynamic that must be considered when researching the topic.

3.1.2. Reproduction and Verification of Research

The quantity and methodology of distributed leadership research has appeared to develop significantly within the past ten years [21], but the field has also been critiqued for lacking methodological rigour [22]. Replicable research of greater methodological rigour is required to determine the link between distributed leadership and organisational commitment, school improvement and female leadership. Further investigation of this nature is also required regarding distributed leadership and other lesser-explored concepts such as job satisfaction, teaching capacity and sense-making.

3.1.3. Conceptualisations of Distributed Leadership

None of the 39 studies included in this entry considered the consistency of research participants’ conceptions of what distributed leadership involves as a base standard to draw comparisons or conclusions from. Furthermore, little research has been conducted to examine the pattern between teachers vs. school leaders’ interpretations of distributed leadership to inform data sampling and analysis procedures. Future studies of the concept can benefit from these findings by investigating distributed leadership in a way that ensures more robust, valid, and reliable data collection.

3.2. Future Directions for Research

3.2.1. Exploration of the Culture Needed for Distributed Leadership to Flourish

The first recommendation for future research arising from this entry is to understand how school culture can improve the adoption of distributed leadership in post-primary schools. School culture and school leadership are inextricably linked [23]. Without researching the intersection between school culture and distributed leadership, the conditions required for distributed leadership to flourish are currently unknown.

3.2.2. Investigation of the Relationship between Distributed Leadership and Policy

The second recommendation arising from this entry is to investigate the influence that national policy on distributed leadership may have on leadership practice in post-primary schools. Distributed leadership is currently the most frequently adopted school leadership theory internationally [5][6] and it appears in policy documents worldwide [1]. Yet, no empirical study in the last decade has investigated the impact that distributed leadership policy has on leadership practice in post-primary schools.

3.2.3. Examination of the Influence of Distributed Leadership on Teacher and Leader Well-Being

The third recommendation arising from this entry is to investigate the influence of distributed leadership on teacher and leader well-being. The management style of a school, defined as the distinctive way in which an organisation makes decisions and discharges various functions [24], as well as the actions of administrators, can significantly affect teachers’ well-being [25]. Distributed leadership has been critiqued for creating increased workload and stress among school staff [26][27][28][29], yet this remains under-interrogated in the literature. It would be of benefit to examine teacher and leader well-being and stress levels in schools where distributed leadership is implemented.

3.2.4. Exploration of Distributed Leadership in Relation to Female Leadership

The fourth recommendation arising from this entry is to explore the relationship between female leadership and distributed leadership. Female leadership is a topic that warrants consideration as a discrepancy has been reported between the percentage of females in the teaching profession in comparison with those in principal positions [30]. This would further clarify the relationship between female leadership and distributed leadership, and further investigate if this has any impact on the number of female-led schools.

3.2.5. Investigation of Teachers’ and Leaders’ Perceptions of Distributed Leadership

The final recommendation arising from this entry is to investigate the perceptions of teachers and leaders of distributed leadership. As outlined in the entry, there are discrepancies among participants’ perceptions of distributed leadership. It is unclear how significant these discrepancies are, if they vary between teachers and school leaders, or if they potentially have a significant impact on data collection and analysis. It is also unclear if an accurate perception of distributed leadership among staff enables more effective distributed leadership, or if differences in perceptions inhibit its effect. This is a distinct gap in the literature that needs to be addressed to further inform distributed leadership practice in schools as well as the rigour of distributed leadership research.

References

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Implications for the role of the principal. J. Manag. Dev. 2011, 31, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.T. Administrative Centralization and Decentralization in France. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1898, 11, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed leadership. In Second International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 653–696. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Friend or foe? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenner, J.A.; Campbell, T. The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 87, 134–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The panorama of the last decade’s theoretical groundings of educational leadership research: A concept co-occurrence network analysis. Educ. Adm. Q. 2018, 54, 327–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngs, H. Distributed Leadership. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gronn, P. Distributed properties: A new architecture for leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. 2000, 28, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolden, R.; Petrov, G.; Gosling, J. Distributed Leadership in Higher Education: Rhetoric and Reality. SAGE J. 2009, 37, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. The New Work of Educational Leaders: Changing Leadership Practice in an Era of School Reform; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, N.; Wise, C.; Woods, P.A.; Harvey, J.A. Distributed Leadership: A Review of Literature; National College for School Leadership: Notthingham, UK, 2003; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J.B.; Spillane, J.P. School leadership and management from a distributed perspective: A 2016 retrospective and prospective. Manag. Educ. 2016, 30, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Conceptual confusion and empirical reticence. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2007, 10, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, R.F. Building a New Structure for School Leadership; Albert Shanker Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J.P. Leadership and learning: Conceptualizing relations between school administrative practice and instructional practice. In How School Leaders Contribute to Student Success; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J.P. Distributed Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, D.; James, K.T.; Denyer, D. Alternative approaches for studying shared and distributed leadership. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanvand, M.M.; Zeinabadi, H.R.; Shomami, M.A. The study of relationship between distributed leadership and principals’ self-efficacy in high schools of Iran. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2013, 3, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbari, M.; Sadeghi, A. Iranian teachers’ perceptions of teacher leadership practices in schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2014, 42, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwinda, A.A. Exploring Teachers’ Perceptions of Distributed Leadership Practices in Selected Secondary Schools within Gauteng Province; University of Johannesburg: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.; Risku, M.; Collin, K. A meta-analysis of distributed leadership from 2002 to 2013: Theory development, empirical evidence and future research focus. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 44, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairon, S.; Goh, J.W. Pursuing the elusive construct of distributed leadership: Is the search over? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 693–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.D.; Deal, T.E. How leaders influence the culture of schools. Educ. Leadersh. 1998, 56, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Khandwalla, P.N. Effective Management Styles: An Indian Study; Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Research and Publication Department: Ahmedabad, India, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, A.G. Teacher Burnout in the Public Schools: Structural Causes and Consequences for Children; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrowetz, D. Making sense of distributed leadership: Exploring the multiple usages of the concept in the field. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liontos, L.B.; Lashway, L. Shared Decision-Making. In School Leadership: Handbook for Excellence; Smith, S.C., Piele, P.K., Eds.; ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management (University of Oregon, United States of America): Eugene, OR, USA, 1997; pp. 226–250. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. Distributed School Leadership: Developing Tomorrow’s Leaders; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Timperley, H.S. Distributed leadership: Developing theory from practice. J. Curric. Stud. 2005, 37, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2016; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]