You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Nengming Lin.

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems are imparted with unique characteristics and specifically deliver loaded drugs at lung cancer tissues on the basis of internal tumor microenvironment or external stimuli.

- stimuli-responsive

- drug delivery

- lung cancer

1. Light-Responsive Nanocarriers

Because of its relative safety and noninvasive character, light has been widely applied for remotely controlled drug delivery [25][1]. Short-wavelength light, including ultraviolet (UV) and visible light, can be utilized to destruct photolabile groups directly for on-demand drug release. However, their limited penetration ability hinders their biomedical application. In contrast to short-wavelength light, near-infrared (NIR) light (780–2500 nm) is able to penetrate deeper through the tissues, and this feature of NIR is preferable for remote control of the desired drug release. To take advantage of both short-wavelength and NIR light, up-conversion nanoparticles (UCNPs), which are capable of transferring NIR light to short-wavelength light, are utilized to fulfill both deep penetration and short-wavelength light-responsive drug release. For example, Ming-Fong Tsai et al. used a UV-responsive o-nitrobenzyl ester (ONB) containing amphiphilic block copolymer to construct a polymersome [26][2]. Then core-shell UCNPs and doxorubicin (DOX) were co-encapsulated to the polymersome, enabling NIR light-inducing photolysis and on-demand drug release for enhanced chemotherapy of lung cancer.

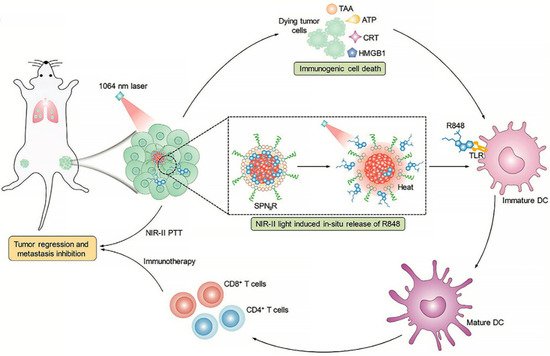

Among multiple therapeutic modalities, immunotherapy is now regarded as the first-line therapy for many cancer indications and revolutionized the field of oncology during the past decade [33][3]. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that phototherapy can trigger immunogenic cell death (ICD) of tumor cells [34][4]. However, with the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, as well as multiple mechanisms involved, adaptive immune resistance may restrain the anti-tumor activity of the ICD cascade. Thus, immunotherapeutic molecules are sometimes introduced into the delivery system for enhanced immunotherapy-assisted synergistic treatment. Additionally, light-controlled release can further raise the specificity [35,36][5][6]. For instance, Jingchao Li et al. proposed a second near-infrared (NIR-II) photothermal immunotherapy using a semiconducting polymer nanoadjuvant (SPNIIR), which was composed of a semiconducting polymer nanoparticle core, a toll-like receptor agonist R848, and a thermally responsive lipid shell (DPPC) [37][7]. Under the irradiation of a NIR-II laser, the thermal effect of the semiconducting polymer nanoparticle core caused the removal of the DPPC shell and induced the on-demand release of R848. Consequently, the synergistic photothermal immunotherapy could suppress primary tumors and eliminate lung metastasis in vivo (Figure 21).

Figure 21. NIR-II light-responsive semiconducting polymer nanoadjuvant (SPNIIR) is designed and applied for synergetic photothermal immunotherapy, not only to the primary and distant tumors but also the metastasis in the lung [37][7]. PTT, photothermal therapy; TLR, toll-like receptor; DC, dendritic cell; R848, a TLR agonist; TAA, tumor-associated antigens; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CRT, calreticulin; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1 protein.

Light-responsive therapeutics exhibit multiple advantages as mentioned above and hold great potential for clinical treatment of lung cancer [41][8]. Furthermore, molecules that absorb light and generate heat or ROS sometimes can also emit fluorescence or transfer the heat to photoacoustic (PA) signal and thus are employed for imaging diagnosis during the therapeutic process. For instance, indocyanine green (ICG) is a typical photothermal molecule and can also be utilized for NIR fluorescence and PA imaging [43][9]. Other fluorescent molecules, such as IR780 [46[10][11],47], Cy7 [48][12], and NIR770 [41][8], are also applied as theranostic agents to the treatment of lung cancer. Ziying Li et al. [48][12] established a chitosan-based nanocomplex CE7Q/CQ/S to deliver molecular-targeted drug erlotinib (Er), Survivin shRNA-expressing plasmid (SV), and Cy7 for simultaneous NIR fluorescence imaging and monitored chemo/gene/photothermal tri-therapies therapy for NSCLC bearing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. With the guidance of NIR imaging, the therapy was more accurate, and the therapeutic outcome was able to be observed in real-time.

2. Ultrasound-Responsive Nanocarriers

Ultrasound (usually defined as > 20 kHz) is widely used for diagnosis and therapy in the clinic [49][13]. Due to its merits in clinical application, including cost-effectiveness, simplicity, and particularly noninvasiveness, ultrasound has been adopted as an external stimulus for smart therapeutics to trigger amplified therapeutic effects. Micro-/nanobubbles, liposomes, liquid perfluorocarbon droplets, micelles, or mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) have been developed as ultrasound-responsive drug carriers after rational design and synthesis.

The fundamental mechanisms underlying ultrasound-mediated therapy mainly include thermal effect, mechanical effect, and chemical effect [50][14]. The thermal effects are attributed to acoustic energy produced by propagating ultrasound. Surrounding biological tissues can absorb part of the energy and thus lead to a temperature increase in the respective areas. Relative high temperature is able to kill cancer cells directly, while hyperthermia (above 80 °C) caused by high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) may be associated with undesired complications, such as second- and third-degree skin burns [51][15]. On the other hand, the temperature increase induced by ultrasound could probably trigger the thermal instability of the drug delivery system and enable targeted controlled drug release.

The mechanical effects are mainly generated from ultrasound pressure, acoustic streaming, and ultrasound-induced oscillation or cavitation [49][13], among which cavitation is often leveraged for drug delivery owing to its specific influence on biological processes.

The chemical effects of ultrasound mediated treatment can also be called sonodynamic therapy (SDT). Oxygen, sonosensitizer, and appropriate ultrasound are three necessary components to complete the process of SDT, and the generation of ROS upon focused ultrasound exposure can cause site-specific profound damage to tumor tissues [53][16]. The combinatorial treatment of SDT with other therapeutic strategies, such as chemotherapy and chemodynamic therapy (CDT), has a synergistic effect in the treatment of lung cancer [54][17].

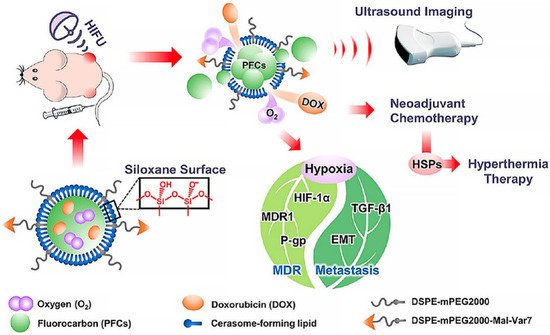

Thermal, mechanical, and chemical effects are not entirely independent and sometimes two or three of them may result in a synergistically therapeutic modality. For instance, Xiaotu Ma et al. fabricated a cerasomal perfluorocarbon nanodroplet (D-vPCs-O2) with an atomic layer of polyorganosiloxane and pH-sensitive tumor-targeting peptide [55][18]. Oxygen and doxorubicin were co-loaded into the nanodroplets. HIFU was utilized to trigger the release of cargoes and simultaneously enhance ultrasound imaging, therefore achieving imaging-guided drug delivery. Mild-temperature HIFU (M-HIFU) could also be applied to slightly elevate tumor temperature and accelerate tumor blood flow. Consequently, ultrasound-triggered oxygen release and temperature elevation jointly relieved tumor hypoxia and alleviated multiple drug resistance, and these two effects jointly enhanced the drug therapeutic efficacy to lung metastasis [56][19] (Figure 32).

Figure 32. Ultrasound-responsive nanodroplets are designed, fabricated, and capable of inhibiting tumor metastasis in the lung [56][19]. HIFU, high intensity focused ultrasound; MDR, multi-drug resistance; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; TGF-β1, Transforming Growth Factor-β1; HSPs, heat-shock proteins.

Two ultrasound parameters, acoustic frequency, and intensity, are often manipulated to induce desired biological effects. For example, Yichen Liu et al. constructed a functionalized smart nano sonosensitizer (EXO-DVDMS) by loading sinoporphyrin sodium (DVDMS), which was an excellent porphyrin sensitizer with both therapeutic and diagnostic features, onto homotypic tumor cell-derived exosomes [53][16]. A guided-ultrasound (US1, 2 W, 3 min) was first introduced to promote the accumulation of EXO-DVDMS in the tumor region, and subsequently, the therapeutic-ultrasound (US2, 3 W, 3 min) was applied for SDT, thus enhancing the targeted delivery of DVDMS to primary as well as metastatic lung tumors. In addition, other external stimuli, such as magnetic fields, can be incorporated with ultrasound-responsive delivery systems and achieve precisely controlled release. Senay Hamarat Sanlier et al. fabricated liposome-based nanobubbles [57][20]. Pemetrexed and pazopanib were conjugated with peptide and then attached to the surface of magnetic nanoparticles. After the functionalized magnetic nanoparticles were encapsulated into the liposomes, pemetrexed and pazopanib carrying nanobubble systems with magnetic responsiveness and ultrasound sensitivity were constructed for NSCLC targeted delivery [58][21]. Furthermore, the inclusion of magnetic nanoparticles can not only enable the magnetic field-guided targeted delivery but also considerably improve both the stability and phase conversion efficiency of nanodroplets.

3. PH-Responsive Nanocarriers

The lactic acid and certain end products produced by lung cancer cells, which are related to an abnormally fast metabolism and proliferation, lead to a more acidic environment (pH 5.7–6.9) in tumor tissues than normal physiological pH (pH 7.4) [59,60][22][23]. pH-sensitive nanoparticles could maximize drug release in the pulmonary tumor microenvironment and minimize drug release en route to the tumor, enhancing the accumulation of nanosystems in the tumor tissue and meanwhile improving the reliability and safety of targeted therapy for lung cancer.

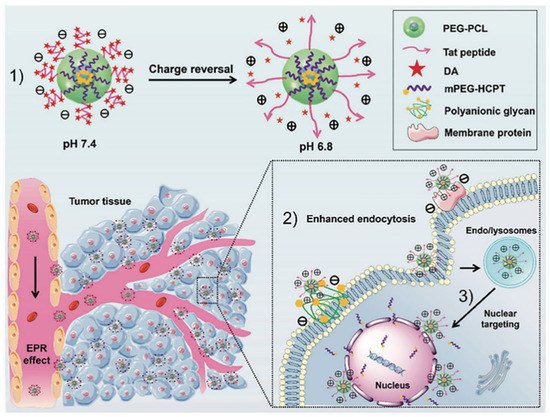

Additionally, the acid pH of the tumor environment also could trigger charge reversal to promote cellular internalization and nuclear entry in the treatment of lung cancer (Figure 43). Nanocarriers with positive surface charge usually bear short blood circulation half-life due to an unspecific adsorption, whereas the addition of TAT peptide would overcome this drawback by improving drug uptake of tumor cells. Anhydride (DA) groups can be utilized to mask the positive charges of TAT. Once the carrier accumulated in the tumor acidic environment, a charge reversal from negative to positive occurred and the targeting ability of TAT was recovered. Zhou et al. generated a DA-TAT carrier for pH-triggered cell uptake and nuclear targeting, which possessed beneficial effects in treating lung metastasis [64][24]. Similarity, Zhao et al. developed a pH-responsive poly(histidine) (PHis) based polymer consisting of a cationic lipid core and a triblock copolymer methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(histidine)-poly(sulfadimethoxine) (mPEG-PHis-PSD or PHD). Acidic pH transformed PSD from a negative to neutral charge, which resulted in a fast dissociation from lipid core, thus achieving tumor-selective accumulation, effective internalization, and efficient anti-tumor activity for NSCLC therapy [65][25].

Figure 43. The concept of pH-triggered cell penetration and nuclear targeting for effective cancer therapy for lung metastatic lung cancer. (1) The schematic diagram of charge reversal; (2) The schematic illustration of targeted transport and enhanced uptake of nanoparticles. (3) Nuclear targeting of positively charged nanoparticles [64][24].

Prodrug-based nanosystem was a great choice with high drug-loading capacity and could load additional drugs for synergistic treatment [66,67][26][27]. Ma and coworkers constructed a pH-sensitive doxorubicin (DOX) prodrug for lung cancer therapy. The hydrophilic segment U11-PEG was introduced to DOX by pH-responsive PHis. Curcumin (CUR) was loaded into DOX-based nanoparticles as a secondary anti-tumor drug. When the prodrug-based codelivery system U11-DOX/CUR nanoparticles were exposed to the tumor acidic microenvironment, DOX and CUR were released simultaneously because of the protonation of pHis. This study suggested that the U11-DOX/CUR nanoparticles are pH-responsive systems and had a potent anti-tumor effect on lung tumor cells [68][28]. Cis-aconitic anhydride-modified doxorubicin (CAD) was designed for pH-sensitive drug release in another study. CAD showed specific distribution in the tumor tissues after 12 h post-injection, exhibiting excellent lung tumor-targeting ability of these nanoparticles. The acid-responsive cis-aconityl linkage between the cis-aconitic anhydride (CA) and antitumor drug DOX could be hydrolyzed, and the release of DOX would accelerate the linkage breakdown once the nanoparticles reached tumor tissues [69][29].

4. Enzyme-Responsive Nanocarriers

Enzymes are essential biomolecules that maintain normal functions of living organisms, e.g., growth, development, metabolism, aging, disease, and immunity. Aberrant enzyme expression was commonly observed in multiple disease-associated microenvironments and cells, especially lung cancer [70,71][30][31]. The overexpressed enzymes mainly include matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), hyaluronidase (HAase), esterase, NAD(P)H, and quinone oxidoreductase1 (NQO1). Enzyme-responsive nanoparticles have attracted considerable attention owing to their selectivity, effectiveness, and rapidity of enzymatic reactions in lung cancer treatment [72,73,74][32][33][34].

Apart from MMPs, HAase is usually combined with other sensitive patterns to generate dual- or multi-responsive nanoparticles to improve lung cancer therapeutic effectiveness. Hyaluronic acid (HA) was used to construct the hydrophilic shell, while hydrophobic compounds could be introduced into the HA backbone by environmentally responsive bonds. For example, Tang’s group utilized pH-sensitive hydrazone bonds to construct enzyme and pH dual-responsive hyaluronic acid nanoparticles [80][35]. In a similar study, He and coworkers designed lung cancer cells’ active-targeting, enzyme, and ROS-sensitive nanoparticles named HPGBCA to deliver afatinib for NSCLC therapy. Poly(glycidylbutylamine) (PGBA) was a cationic amphiphilic compound with a ROS-sensitive thioether linker. The anionic HA shell could actively target CD44 receptor-overexpressed tumor cells and mask the positive charge of PGBA for long circulation in the bloodstream. When HPGBCA reached HAase-enriched lung tumor sites, the HA shell was degraded to expose positively charged cores and accelerate the lysosomal escape. Subsequently, the Ce6 of HPGBCA could produce ROS under NIR irradiation to trigger the oxidation of ROS-sensitive linkers for drug release [31][36].

The esterase-sensitive nanocarrier is also a great choice in enzyme-responsive drug delivery systems for the lung. A nanoparticle named HAPBA, which was designed by Cho and coworkers for lung cancer therapy, would release drugs at esterase-enriched tumor tissue environment. Ester bonds were used to join 4-Phenylbutyric acid (PBA) and HA backbone for the quick release of curcumin and PBA. PBA was not only the hydrophobic segment in the structure of these nanoparticles but also an efficient inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDAC). The cleavage of ester bonds realized the rapid release of curcumin and PBA, exhibiting efficient tumor growth suppression in lung adenocarcinoma [81][37]. Similarly, Ren et al. designed a gold nanorod–curcumin conjugate held together by an esterase-labile ester bond. This conjugate showed a rapid and sustained release of curcumin. In the absence of esterase, encapsulated drugs were completely restricted inside the nanoparticles. When the concentration of esterase increased, an abrupt curcumin release was observed, suggesting that ester hydrolysis was an essential trigger of drug release. As a result, the introduction of the ester bond enhanced the inhibitory effects of the nanorod–curcumin conjugate on human lung cancer A549 cells [45][38].

NQO1 enzyme is a cytosolic reductase that is abnormally overexpressed in multiple cancers, including lung cancer [82,83][39][40]. Trimethyl-locked quinone propionic acid (QPA) reacts with NQO1 to form a lactone-based group via intramolecular cyclization. To take advantage of the fundamental features of NQO1, an NQO1-responsive nanoparticle termed QPA-P was designed by Kim et al. for lung cancer therapy. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) was used as the hydrophilic segment and QPA-locked polycaprolactone (PCL), which was conditionally triggered by NQO1, was the hydrophobic tail that imparted amphiphilic property to QPA-P. After a cascade two-step cyclization process with the NQO1 enzyme, the particle size of QPA-P increased and loaded DOX rapidly released into surrounding medium and tumor cells, indicating that NQO1-sensitive micelles were promising for drug delivery in lung cancer [84][41].

References

- Li, F.; Qin, Y.; Lee, J.; Liao, H.; Wang, N.; Davis, T.P.; Qiao, R.; Ling, D. Stimuli-responsive nano-assemblies for remotely controlled drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2020, 322, 566–592.

- Tsai, M.-F.; Lo, Y.-L.; Soorni, Y.; Su, C.-H.; Sivasoorian, S.S.; Yang, J.-Y.; Wang, L.-F. Near-infrared light-triggered drug release from ultraviolet- and redox-responsive polymersome encapsulated with core–shell upconversion nanoparticles for cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2021, 4, 3264–3275.

- Waldman, A.D.; Fritz, J.M.; Lenardo, M.J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: From T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 651–668.

- Jin, F.; Qi, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, D.; You, Y.; Shu, G.; Du, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, M.; et al. NIR-Triggered Sequentially Responsive Nanocarriers Amplified Cascade Synergistic Effect of Chemo-Photodynamic Therapy with Inspired Antitumor Immunity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 32372–32387.

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, J.; Xu, C.; Pu, K. Activatable polymer nanoagonist for second near-infrared photothermal immunotherapy of cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 742.

- Feng, B.; Hou, B.; Xu, Z.; Saeed, M.; Yu, H.; Li, Y. Self-amplified drug delivery with light-inducible nanocargoes to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1902960.

- Li, J.; Yu, X.; Jiang, Y.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Pu, K. Second near-infrared photothermal semiconducting polymer nanoadjuvant for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2003458.

- Gou, S.; Yang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zu, M.; Kang, T.; Liu, S.; Ke, B.; Xiao, B. Multi-responsive nanococktails with programmable targeting capacity for imaging-guided mitochondrial phototherapy combined with chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2020, 327, 371–383.

- Zhu, Q.; Fan, Z.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y.; Hou, Z.; Zhu, X. Self-distinguishing and stimulus-responsive carrier-free theranostic nanoagents for imaging-guided chemo-photothermal therapy in small-cell lung cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 51314–51328.

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Sun, S.; Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Hou, R.; Liang, X. Anti-tumor metastasis via platelet inhibitor combined with photothermal therapy under activatable fluorescence/magnetic resonance bimodal imaging guidance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 19679–19694.

- Yang, Z.; Cheng, R.; Zhao, C.; Sun, N.; Luo, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Tian, Z. Thermo- and pH-dual responsive polymeric micelles with upper critical solution temperature behavior for photoacoustic imaging-guided synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy against subcutaneous and metastatic breast tumors. Theranostics 2018, 8, 4097–4115.

- Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Liu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Ye, J.; Li, B.; Chen, H.; Gao, Y. Near-infrared/pH dual-responsive nanocomplexes for targeted imaging and chemo/gene/photothermal tri-therapies of non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Biomater. 2020, 107, 242–259.

- Cai, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, M.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, F.; Leung, W.; Xu, C. Ultrasound-responsive materials for drug/gene delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1650.

- Entzian, K.; Aigner, A. Drug delivery by ultrasound-responsive nanocarriers for cancer treatment. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1135.

- Awad, N.S.; Paul, V.; AlSawaftah, N.M.; Ter Haar, G.; Allen, T.M.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. Ultrasound-responsive nanocarriers in cancer treatment: A review. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 589–612.

- Liu, Y.; Bai, L.; Guo, K.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Q.; Wang, P.; Wang, X. Focused ultrasound-augmented targeting delivery of nanosonosensitizers from homogenous exosomes for enhanced sonodynamic cancer therapy. Theranostics 2019, 9, 5261–5281.

- Zhang, Y.; Khan, A.R.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhai, G. A sonosensitiser-based polymeric nanoplatform for chemo-sonodynamic combination therapy of lung cancer. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 57.

- Fu, S.; Yang, R.; Ren, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Kang, Y.; Xue, P. Catalytically active CoFe2O4 nanoflowers for augmented sonodynamic and chemodynamic combination therapy with elicitation of robust immune response. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 11953–11969.

- Ma, X.; Yao, M.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Luo, Q.; Hou, R.; Liang, X.; Wang, F. High intensity focused ultrasound-responsive and ultrastable cerasomal perfluorocarbon nanodroplets for alleviating tumor multidrug resistance and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 15904–15918.

- Lee, J.Y.; Crake, C.; Teo, B.; Carugo, D.; de Saint Victor, M.; Seth, A.; Stride, E. Ultrasound-enhanced siRNA delivery using magnetic nanoparticle-loaded chitosan-deoxycholic acid nanodroplets. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1601246.

- Hamarat Sanlier, S.; Ak, G.; Yilmaz, H.; Unal, A.; Bozkaya, U.F.; Taniyan, G.; Yildirim, Y.; Yildiz Turkyilmaz, G. Development of ultrasound-triggered and magnetic-targeted nanobubble system for dual-drug delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1272–1283.

- Kanamala, M.; Wilson, W.R.; Yang, M.; Palmer, B.D.; Wu, Z. Mechanisms and biomaterials in pH-responsive tumour targeted drug delivery: A review. Biomaterials 2016, 85, 152–167.

- Shi, J.; Ren, Y.; Ma, J.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Gu, H.; Fu, C.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J. Novel CD44-targeting and pH/redox-dual-stimuli-responsive core-shell nanoparticles loading triptolide combats breast cancer growth and lung metastasis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 188.

- Jing, Y.; Xiong, X.; Ming, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, G.; Zhou, S. A Multifunctional micellar nanoplatform with pH-triggered cell penetration and nuclear targeting for effective cancer therapy and inhibition to lung metastasis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, e1700974.

- Shi, M.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Pan, S.; Yang, C.; Wei, Y.; Hu, H.; Qiao, M.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X. pH-responsive hybrid nanoparticle with enhanced dissociation characteristic for siRNA delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 6885–6902.

- Zhang, R.; Ru, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Mao, S. Layer-by-layer nanoparticles co-loading gemcitabine and platinum (IV) prodrugs for synergistic combination therapy of lung cancer. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2017, 11, 2631–2642.

- Yu, J.; Li, W.; Yu, D. Atrial natriuretic peptide modified oleate adenosine prodrug lipid nanocarriers for the treatment of myocardial infarction: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2018, 12, 1697–1706.

- Hong, Y.; Che, S.; Hui, B.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Qiang, Y.; Ma, H. Lung cancer therapy using doxorubicin and curcumin combination: Targeted prodrug based, pH sensitive nanomedicine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108614.

- Xia, F.; Hou, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhi, X.; Cheng, J.; de la Fuente, J.M.; Song, J.; Cui, D. pH-responsive gold nanoclusters-based nanoprobes for lung cancer targeted near-infrared fluorescence imaging and chemo-photodynamic therapy. Acta Biomater. 2018, 68, 308–319.

- Chen, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Dai, H.; Pang, S.; Lei, L.; Ji, J.; Wang, B. Design of smart targeted and responsive drug delivery systems with enhanced antibacterial properties. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 20946–20962.

- Sharma, A.; Kim, E.J.; Shi, H.; Lee, J.Y.; Chung, B.G.; Kim, J.S. Development of a theranostic prodrug for colon cancer therapy by combining ligand-targeted delivery and enzyme-stimulated activation. Biomaterials 2018, 155, 145–151.

- Shahriari, M.; Zahiri, M.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M. Enzyme responsive drug delivery systems in cancer treatment. J. Control Release 2019, 308, 172–189.

- Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, F.; Sun, J.; Yuan, H. Lipase-triggered water-responsive “Pandora’s Box” for cancer therapy: Toward induced neighboring effect and enhanced drug penetration. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1706407.

- Wang, X.; Gu, M.; Toh, T.B.; Abdullah, N.L.B.; Chow, E.K. Stimuli-responsive nanodiamond-based biosensor for enhanced metastatic tumor site detection. SLAS Technol. 2018, 23, 44–56.

- Ren, Q.; Liang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Gong, P.; Zhou, L.; Sun, Z.; Xiang, J.; Xu, Z.; Peng, X.; Li, S.; et al. Enzyme and pH dual-responsive hyaluronic acid nanoparticles mediated combination of photodynamic therapy and chemotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 845–852.

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Cai, S.; Mei, H.; He, Y.; Huang, D.; Shi, W.; Li, S.; Cao, J.; He, B. Photo-induced specific intracellular release EGFR inhibitor from enzyme/ROS-dual sensitive nano-platforms for molecular targeted-photodynamic combinational therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 7931–7940.

- Lee, S.Y.; Hong, E.H.; Jeong, J.Y.; Cho, J.; Seo, J.H.; Ko, H.J.; Cho, H.J. Esterase-sensitive cleavable histone deacetylase inhibitor-coupled hyaluronic acid nanoparticles for boosting anticancer activities against lung adenocarcinoma. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 4624–4635.

- Zhu, F.; Tan, G.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ren, F. Rational design of multi-stimuli-responsive gold nanorod-curcumin conjugates for chemo-photothermal synergistic cancer therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 2905–2917.

- Gong, Q.; Yang, F.; Hu, J.; Li, T.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Rational designed highly sensitive NQO1-activated near-infrared fluorescent probe combined with NQO1 substrates in vivo: An innovative strategy for NQO1-overexpressing cancer theranostics. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113707.

- Pradubyat, N.; Sakunrangsit, N.; Mutirangura, A.; Ketchart, W. NADPH: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) mediated anti-cancer effects of plumbagin in endocrine resistant MCF7 breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine 2020, 66, 153133.

- Park, J.; Jo, S.; Lee, Y.M.; Saravanakumar, G.; Lee, J.; Park, D.; Kim, W.J. Enzyme-triggered disassembly of polymeric micelles by controlled depolymerization via cascade cyclization for anticancer drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 8060–8070.

More