Children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities (ID) have low levels of physical activity (PA). Understanding factors influencing the PA participation of this population is essential to the design of effective interventions. Continued exploration of factors influencing PA participation is required among children and adolescents with ID. Future interventions should involve families, schools, and wider support network in promoting their PA participation together.

- children and adolescents

- intellectual disability

- physical activity

- barriers

- facilitators

- scoping review

1. Introduction

2. Current Insights

2.1. Searching Results

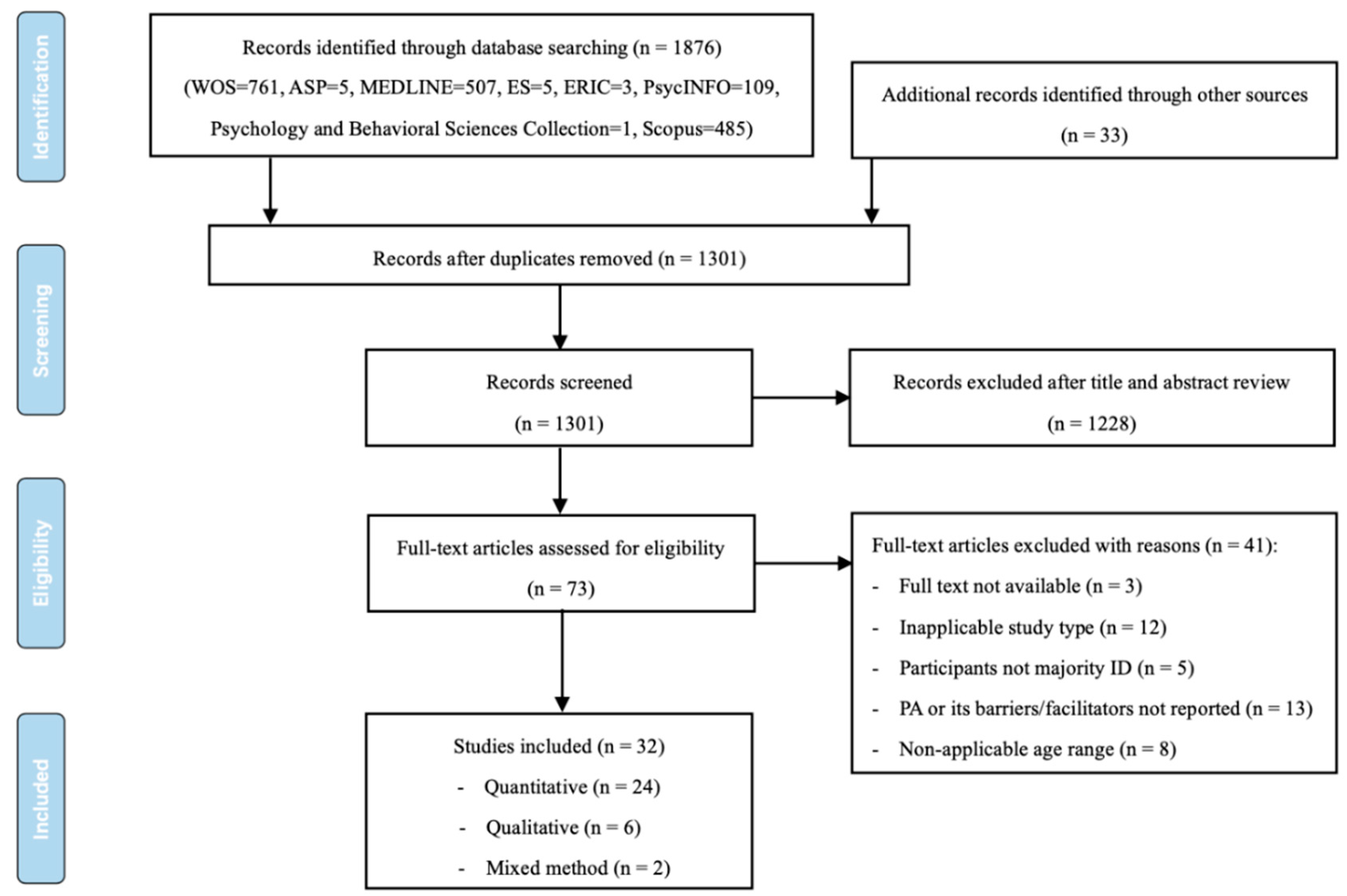

The initial search identified 1876 studies (WOS, n = 761; ASP, n = 5; MEDLINE, n = 507; ES, n = 5; ERIC, n = 3; PsycINFO, n = 109; Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, n = 1; Scopus, n = 485). Thirty-three additional studies were identified through related reviews. After removing duplicates from the original sample (n = 1909), title and abstract screening of 1301 articles was performed, from which 1228 studies were excluded. The researchers read the full text of the remaining 73 articles and excluded another 41. Finally, 32 studies were included in this research.2.1. Searching Results

Figure 1.

Figure 1.2.2. Study Characteristics

2.2. Study Characteristics

| First Author (Year) |

Type of Study |

Geographic Location |

Sampling Strategy |

Participant Details | Theory | Research | Design | Measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Themes | Dimensions of PA | |||||||

| Sample Size | Age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensities of PA | ||||||||

| Gender |

|---|

| ID Level |

|---|

| Steps | ||||||||||||

| Subjective PA Questionnaires | N/A | |||||||||||

| LPA | MPA | MVPA | Steps/Day | -Average Daily Steps Counts | Regular PA (Yes or No) | PA Frequency (Times Per Week) | PA Perceptual | Characteristics (Perceived | Exertion) | |||

| Barriers | ||||||||||||

| Individual factors | ||||||||||||

| - Physiological factors | ||||||||||||

| Conditions associated with ID | [29][31][37] | |||||||||||

| - Motor development | ||||||||||||

| Low motor development | [9] | [13][25] | ||||||||||

| - Cognitive and psychological factors | ||||||||||||

| Low self-efficacy | [23] | [18] | ||||||||||

| Lack of understanding about importance of PA and its benefits to health | [28] | |||||||||||

| Preference for indoor activities | [42] | |||||||||||

| Interpersonal factors | ||||||||||||

| - Family | ||||||||||||

| Lack of parental support | [39] | [26][29][31][37] | ||||||||||

| Parents’ vigilance and overprotection | [26][31] | |||||||||||

| - Social network | ||||||||||||

| Lack of social network | [23] | [18] | ||||||||||

| Environmental factors | ||||||||||||

| - Social environment | ||||||||||||

| Inadequate or inaccessible facilities | [26] | |||||||||||

| Lack of appropriate programs | [31][37] | |||||||||||

| Lack of public transportation | [39] | |||||||||||

| - School environment | ||||||||||||

| Lesson contexts (management) | [36] | |||||||||||

| Teaching behaviors (transmit knowledge) | [36] | |||||||||||

| - Natural environment | ||||||||||||

| Poor weather | [18][26] | |||||||||||

| Facilitators | ||||||||||||

| Individual factors | ||||||||||||

| - Physical abilities | ||||||||||||

| Physical skills | [33] | [31] | ||||||||||

| - Cognitive and psychological factors | ||||||||||||

| High self-efficacy | [23] | [18] | ||||||||||

| Weight loss | [20] | |||||||||||

| Enjoyment of PA | [24] | [24] | [23] | [28][29] | ||||||||

| Personality traits | [31] | |||||||||||

| Caregiver’s high educational level | [34] | |||||||||||

| Interpersonal factors | ||||||||||||

| - Family | ||||||||||||

| Sufficient parental support | [17] | [18][28][29][31][37] | ||||||||||

| Positive parental beliefs | [21] | |||||||||||

| Positive role of siblings | [31][37] | |||||||||||

| - Social network | ||||||||||||

| Positive social interaction with peers | [11][32] | [18][29][31][37] | ||||||||||

| Positive coach–athlete relationship | [17] | |||||||||||

| Environmental factors | ||||||||||||

| - Social environment | ||||||||||||

| An exergaming context | [14] | |||||||||||

| Adequate and available resources | [17] | |||||||||||

| Adapted PA programs | [30] | [19][33] | [31] | |||||||||

| - School environment | ||||||||||||

| Attending PE classes and participating PA during recess | [20][27][35][38][40][41] | [22][25] | [18] | |||||||||

| Inclusive PE programs | [15] | [15] | ||||||||||

| High autonomy–supportive climates on PA | [16] | |||||||||||

| Lesson contexts (skill practice) | [36] | |||||||||||

| Teaching methods | [ | |||||||||||

| Alhusaini (2020) | [13] | Quantitative | Saudi Arabia | purposive | 78 (37DS/41TD) |

8–12 | male | DS | n/a | cross-sectional | pedometer | |

| Pincus (2019) | [14] | Quantitative | USA | purposive | 3 | 16–18 | 1 male 2 female |

moderate sever unspecified |

n/a | intervention | quantitative observation (OSRAC-H) |

|

| Wouters (2019) | [9] | Quantitative | Netherlands | purposive | 68 | 2–18 | 43 male 25 female |

moderate to severe | n/a | cross-sectional | accelerometer | |

| Gobbi (2018) | [15] | Quantitative | Italy | convenience | 19 | 17.4 ± 1.7 | 15 male 4 female |

mild to moderate | n/a | case study | accelerometer questionnaire |

|

| Johnson (2018) | [16] | Quantitative | USA | could not be determined | 32 (14DD/18TD) |

5–9 (6.89 ± 1.11) |

9/11 male 5/7 female |

DD | self-determination theory | intervention | accelerometer | |

| Robertson (2018) | [11] | Quantitative | UK | purposive | 535 | 13–20 | 356 male 179 female |

mild to moderate | n/a | longitudinal | questionnaire | |

| Ryan (2018) | [17] | Quantitative | Canada | purposive | 409 | 11–23 | 261 male 148 female |

ASD ID |

n/a | cross-sectional | questionnaire | |

| Stevens (2018) | [18] | Qualitative | UK | purposive | 10 | 16–18 | 7 male 3 female |

mild to moderate | Self-Determination Theory | phenomenology | semi-structured interview |

|

| Ptomey (2017) | [19] | Mixed method | USA | could not be determined | 31 | 11–21 (13.9 ± 2.7) |

16 male 15 female |

mild to moderate IDD | n/a | intervention | heart rate monitors, questionnaire, semi-structured interviews |

|

| Einarsson (2016) | [20] | Quantitative | Iceland | convenience | 184 (91ID/93TD) |

6–16 | could not be determined | mild to severe | n/a | cross-sectional | accelerometers, questionnaire |

|

| Pitchford (2016) | [21] | Quantitative | USA | convenience | 113 | 2–21 | 72 male 41 female |

DD | n/a | cross-sectional | questionnaire | |

| Queralt (2016) | [22] | Quantitative | Spain | convenience | 35 | 15.3 ± 2.7 | 22 male 13 female |

mild to moderate | n/a | cross-sectional descriptive |

pedometers | |

| Stanish (2016) | [23] | Quantitative | USA | could not be determined | 98 (38ID/60TD) |

13–21 | 17/36 male 21/24 female |

mild to moderate | social cognitive | cross-sectional | questionnaire | |

| Boddy (2015) | [24] | Quantitative | UK | convenience | 70 | 5–15 | 57 male 13 female |

ASD non-ASD |

n/a | cross-sectional | accelerometers, quantitative observation (SOCARP) |

|

| Eguia (2015) | [25] | Quantitative | Philippines | convenience | 60 | 5–14 | 51 male 9 female |

mild to moderate | n/a | cross-sectional | pedometers | |

| Njelesani (2015) | [26] | Qualitative | Trinidad and Tobago | purposive | 9(parent) | (child) 10–17 |

(child) 6 male 3 female |

moderate to severe DD | occupational perspective |

phenomenology | semi-structured interviews, in-depth interviews |

|

| Pan (2015) | [27] | Quantitative | China (Taiwan) |

convenience | 80 (40D/40TD) |

12–17 | 30/30 male 10/10 female |

21 slight 14 medium ID 3 high ID 2 total ID |

n/a | cross-sectional | accelerometer | |

| Downs (2014) | [28] | Qualitative | UK | purposive | 23 (teachers) | (child) 4–18 |

(teacher) 9 male 14 femle |

ID level could not be determined | n/a | phenomenology | semi-structured focus groups |

|

| Downs (2013) | [29] | Qualitative | UK | purposive | 8 | 6–21 (16.38 ± 5.04) |

3 male 5 female |

DS | n/a | phenomenology | semi-structured interview |

|

| Shields (2013) | [30] | Quantitative | Australia | could not be determined | 68 | 17.9 ± 2.6 | 30 male 38 female |

mild to moderate DS | n/a | intervention (RCT) |

accelerometer | |

| Barr (2011) | [31] | Qualitative | Australia | purposive | 20 (parent) | (child)2–17 (9.9 ± 4.8) |

10 female 6 male |

DS | n/a | phenomenology | In-depth interview | |

| Temple (2011) | [32] | Quantitative | Canada | could not be determined | 34 (20ID/14TD) |

ID 17.8 ± 1.6 TD 16.4 ± 1.3 |

10/5 male 10/9 female |

mild to moderate | n/a | intervention | questionnaire | |

| Ulrich (2011) | [33] | Quantitative | USA | convenience | 46 | 8–15 | 20 male 26 male |

DS | the principles of dynamic systems theory | intervention (RCT) |

accelerometers | |

| Lin (2010) | [34] | Quantitative | China (Taiwan) |

could not be determined | 350 | 16–18 | 211 male 139 female |

mild to profound | n/a | cross-sectional | questionnaire | |

| Pitetti (2009) | [35] | Quantitative | USA | purposive | 15 | 8.8 ± 2.2 | 6 male 9 female |

mild | n/a | cross-sectional | heart rate monitor | |

| Sit (2008) | [36] | Quantitative | China (Hong Kong) |

purposive | 80 | 4–6 grades | 54 male 26 female |

mild | n/a | cross-sectional | quantitative observation (SOFIT) | |

| Menear (2007) | [37] | Qualitative | USA | purposive | 21 | (child) 3–22 |

13 male 8 female |

DS | n/a | phenomenology | focus group | |

| Faison-Hodge (2004) | [38] | Quantitative | USA | convenience | 46 (8MR/38TD) |

8–11 | 25 male 21 female |

mild MR | social cognitive theory | cross-sectional | quantitative observation (SOFIT), heart rate monitor |

|

| Kozub (2003) | [39] | Mixed method | USA | could not be determined | 7 | 13–25 | 4 male 3 female |

MR | n/a | cross-sectional | accelerometers, quantitative observation (CPAF), semi-structured interview |

|

| Horvat (2001) | [40] | Quantitative | USA | purposive | 23 | 6.5–12 | could not be determined | mild MR | n/a | cross-sectional | heart rate monitor, accelerometers, quantitative observation |

|

| Lorenzi (2000) | [41] | Quantitative | USA | purposive | 34 (17MR/17TD) |

5.5–12 | 10/10 male 7/7 female |

mild MR | n/a | cross-sectional | heart rate monitor, accelerometers, quantitative observation (SOAL) |

|

| Sharav (1992) | [42] | Quantitative | Canada | convenience | 60 (30DS/30TD) |

2 –11 | could not be determined | DS | n/a | cross-sectional | questionnaire | |

2.3. Thematic Synthesis

The barriers and facilitators of PA participation among children and adolescents with ID are classified into three groups of studies using different research methods. Specifically, barriers and facilitators are presented under individual, interpersonal, and environmental levels of influence based on the social ecological model2.3. Thematic Synthesis

| 28 |

| ] |

| A strong home-school link |

| [ |

| 28 |

| ] |

2.3.1. Barriers to Participating in PA

Qualitative Studies

The included qualitative studies identified barriers to PA participation among children and adolescents with ID based on the perceptions of parents, teachers, and adolescents with ID. Any dimension of PA was not available in these studies. At the individual level, the results of studies showed that conditions associated with ID, such as developmental delays2.3.1. Barriers to Participating in PA

Qualitative Studies

Quantitative Studies

Mixed-Method Studies

2.3.2. Facilitators of Participating in PA

Qualitative Studies

Facilitators of PA participation among children and adolescents with ID reported by the included qualitative studies were also identified from perceptions of parents, teachers, and adolescents with ID. At the individual level, physical skills were identified as facilitators of participating in PA among children and adolescents with ID2.3.2. Facilitators of Participating in PA

Qualitative Studies

Quantitative Studies

At the individual level, physical skills (e.g., riding a bicycle) were identified as physical ability factors that influence MVPA among children and adolescents with IDQuantitative Studies

Mixed-Method Studies

An adapted PA program using group video conferencing for the promotion of PAMixed-Method Studies

3. Conclusions

Based on the social ecological model, the ouresearchers' synthesis of the studies identified 34 factors primarily related to individual, interpersonal, and environmental elements at several levels of influence. Disability-specific factors, low self-efficacy, lack of parental support, inadequate or inac-cessible facilities, and lack of appropriate programs were the most commonly reported barriers. High self-efficacy, enjoyment of PA, sufficient parental support, social interaction with peers, attending school PE classes, and adapted PA programs were the most commonly reported facilitators. Given the findings from this scoping review, there is a need for continued exploration of the barriers and facilitators of PA participation among children and adolescents with ID by more qualitative, longitudinal, and interventional studies. By understanding the relationships between barriers and facilitators and the different dimensions of PA, interventions can be better designed and adapted to en-courage greater PA participation for children and adolescents. Such work may be vital to improve this population’s health and growth.

References

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131.

- Ahn, S.; Fedewa, A.L. A meta-analysis of the relationship between children’s physical activity and mental health. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 385–397.

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895.

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40.

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; p. 7.

- Esposito, P.E.; MacDonald, M.; Hornyak, J.E.; Ulrich, D.A. Physical activity patterns of youth with Down syndrome. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 50, 109–119.

- Izquierdo-Gomez, R.; Martínez-Gómez, D.; Acha, A.; Veiga, O.L.; Villagra, A.; Diaz-Cueto, M. Objective assessment of sedentary time and physical activity throughout the week in adolescents with Down syndrome. The UP&DOWN study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 482–489.

- Wouters, M.; Evenhuis, H.M.; Hilgenkamp, T.I.M. Physical activity levels of children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 131–142.

- Einarsson, I.Ó.; Ólafsson, Á.; Hinriksdóttir, G.; Jóhannsson, E.; Daly, D.; Arngrímsson, S.Á. Differences in physical activity among youth with and without intellectual disability. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 411–418.

- Robertson, J.; Emerson, E.; Baines, S.; Hatton, C. Self-reported participation in sport/exercise among adolescents and young adults with and without mild to moderate intellectual disability. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 247–254.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012.

- Alhusaini, A.A.; Ali Al-Walah, M.; Melam, G.R.; Buragadda, S. Variables correlated with physical activity and conformance to physical activity guidelines in healthy children and children with Down syndrome. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Kurortmed. 2020, 59, 141–145.

- Pincus, S.M.; Hausman, N.L.; Borrero, J.C.; Kahng, S. Context influences preference for and level of physical activity of adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2019, 52, 788–795.

- Gobbi, E.; Greguol, M.; Carraro, A. Brief report: Exploring the benefits of a peer-tutored physical education programme among high school students with intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 937–941.

- Johnson, J.L.; Miedema, B.; Converse, B.; Hill, D.; Buchanan, A.M.; Bridges, C.; Irwin, J.M.; Rudisill, M.E.; Pangelinan, M. Influence of high and low autonomy-supportive climates on physical activity in children with and without developmental disability. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2018, 30, 427–437.

- Ryan, S.; Fraser-Thomas, J.; Weiss, J.A. Patterns of sport participation for youth with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 369–378.

- Stevens, G.; Jahoda, A.; Matthews, L.; Hankey, C.; Melville, C.; Murray, H.; Mitchell, F. A theory-informed qualitative exploration of social and environmental determinants of physical activity and dietary choices in adolescents with intellectual disabilities in their final year of school. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 52–67.

- Ptomey, L.T.; Willis, E.A.; Greene, J.L.; Danon, J.C.; Chumley, T.K.; Washburn, R.A.; Donnelly, J.E. The feasibility of group video conferencing for promotion of physical activity in adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 122, 525–538.

- Einarsson, I.Þ.; Jóhannsson, E.; Daly, D.; Arngrímsson, S.Á. Physical activity during school and after school among youth with and without intellectual disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 56, 60–70.

- Pitchford, E.A.; Siebert, E.; Hamm, J.; Yun, J. Parental perceptions of physical activity benefits for youth with developmental disabilities. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 121, 25–32.

- Queralt, A.; Vicente-Ortiz, A.; Molina-García, J. The physical activity patterns of adolescents with intellectual disabilities: A descriptive study. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 341–345.

- Stanish, H.I.; Curtin, C.; Must, A.; Phillips, S.; Maslin, M.; Bandini, L.G. Physical activity enjoyment, perceived barriers, and beliefs among adolescents with and without intellectual disabilities. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 102–110.

- Boddy, L.M.; Downs, S.J.; Knowles, Z.R.; Fairclough, S.J. Physical activity and play behaviours in children and young people with intellectual disabilities: A cross-sectional observational study. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2015, 36, 154–171.

- Eguia, K.F.; Capio, C.M.; Simons, J. Object control skills influence the physical activity of children with intellectual disability in a developing country: The Philippines. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 40, 265–274.

- Njelesani, J.; Leckie, K.; Drummond, J.; Cameron, D. Parental perceptions of barriers to physical activity in children with developmental disabilities living in Trinidad and Tobago. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 290–295.

- Pan, C.-Y.; Liu, C.-W.; Chung, I.C.; Hsu, P.-J. Physical activity levels of adolescents with and without intellectual disabilities during physical education and recess. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 36, 579–586.

- Downs, S.J.; Knowles, Z.R.; Fairclough, S.J.; Heffernan, N.; Whitehead, S.; Halliwell, S.; Boddy, L.M. Exploring teachers’ perceptions on physical activity engagement for children and young people with intellectual disabilities. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 402–414.

- Downs, S.J.; Boddy, L.M.; Knowles, Z.R.; Fairclough, S.J.; Stratton, G. Exploring opportunities available and perceived barriers to physical activity engagement in children and young people with Down syndrome. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2013, 28, 270–287.

- Shields, N.; Taylor, N.F.; Wee, E.; Wollersheim, D.; O’Shea, S.D.; Fernhall, B. A community-based strength training programme increases muscle strength and physical activity in young people with Down syndrome: A randomised controlled trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 4385–4394.

- Barr, M.; Shields, N. Identifying the barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1020–1033.

- Temple, V.A.; Stanish, H.I. The feasibility of using a peer-guided model to enhance participation in community-based physical activity for youth with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2011, 15, 209–217.

- Ulrich, D.A.; Burghardt, A.R.; Lloyd, M.; Tiernan, C.; Hornyak, J.E. Physical activity benefits of learning to ride a two-wheel bicycle for children with Down syndrome: A randomized trial. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 1463–1477.

- Lin, J.-D.; Lin, P.-Y.; Lin, L.-P.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Wu, S.-R.; Wu, J.-L. Physical activity and its determinants among adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 31, 263–269.

- Pitetti, K.H.; Beets, M.W.; Combs, C. Physical activity levels of children with intellectual disabilities during school. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1580–1586.

- Sit, C.H.P.; McKenzie, T.L.; Lian, J.M.G.; McManus, A. Activity levels during physical education and recess in two special schools for children with mild intellectual disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2008, 25, 247–259.

- Menear, K. Parents’ perceptions of health and physical activity needs of children with Down syndrome. Down Syndr. Res. Pract. 2007, 12, 60–68.

- Faison-Hodge, J.; Porretta, D.L. Physical activity levels of students with mental retardation and students without disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2004, 21, 139–152.

- Kozub, F.M. Explaining physical activity in individuals with mental retardation: An exploratory study. Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 2003, 38, 302–313.

- Horvat, M.; Franklin, C. The effects of the environment on physical activity patterns of children with mental retardation. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2001, 72, 189–195.

- Lorenzi, D.G.; Horvat, M.; Pellegrini, A.D. Physical activity of children with and without mental retardation in inclusive recess settings. Educ. Train. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. 2000, 35, 160–167.

- Sharav, T.; Bowman, T. Dietary practices, physical activity, and body-mass index in a selected population of Down syndrome children and their siblings. Clin. Pediatr. 1992, 31, 341–344.

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E.B. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 465–482.

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377.

- Brennan, M.C.; Brown, J.A.; Ntoumanis, N.; Leslie, G.D. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity participation in adults living with type 1 diabetes: A systematic scoping review. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 46, 95–107.

- Bossink, L.W.M.; van der Putten, A.A.; Vlaskamp, C. Understanding low levels of physical activity in people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review to identify barriers and facilitators. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 68, 95–110.

- Whitt-Glover, M.C.; O’Neill, K.L.; Stettler, N. Physical activity patterns in children with and without Down syndrome. Pediatr. Rehabil. 2006, 9, 158–164.

- Glowacki, K.; Duncan, M.J.; Gainforth, H.; Faulkner, G. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity and exercise among adults with depression: A scoping review. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 13, 108–119.

- Gourlan, M.; Bernard, P.; Bortolon, C.; Romain, A.J.; Lareyre, O.; Carayol, M.; Ninot, G.; Boiché, J. Efficacy of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 10, 50–66.