In the context of open innovation, enterprises’ thirst for innovation resources is increasing day by day. Faced with limited resources, innovation search behavior, as a way to collect and learn information such as knowledge and technology to increase the novelty of resources, is an important way for enterprises to break through the status quo in order to obtain a wider range of resources and improve the innovation of enterprises. However, in the existing literature, there are many studies on the impact of innovation search behavior on innovation performance, but the existing studies are scarce and paradoxical regarding the influencing factors of antecedent variables of innovation. In today’s rapidly evolving society with faster product iterations and changing consumer needs, the market competition environment is becoming increasingly fierce, which leads to higher standards for enterprises to carry out innovation activities. More and more enterprise managers find that by relying on their own resources, they cannot adapt to the changing market environment and cannot obtain sustainable innovation advantages. Enterprises need to actively conduct innovative search behaviors to obtain resources according to their own state, and innovative resources need not only include internal resources but also external resources, which are open. In this context, the open innovation behavior of enterprises is promoted through innovation search behavior, and sustainable competitive advantages are obtained to ensure the sustainable development of enterprises.

- positive performance feedback

- innovation search

- regulatory focus

- sustainable development

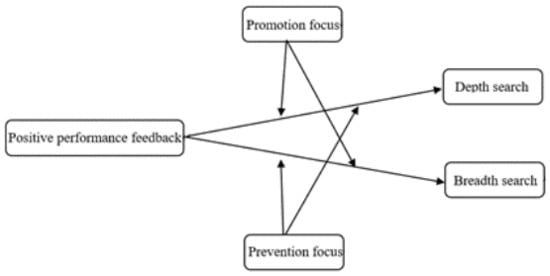

1. Positive Performance Feedback and Innovation Search

2. Moderating Role of Regulatory Focus: CEO Regulatory Focus

2.1. CEO Promotion Focus

2.2. CEO Prevention Focus

References

- Chen, W.R. Determinants of Firms’ Backward- and Forward-Looking R&D Search Behavior. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 609–622.

- Bromiley, P.; Washburn, M. Cost reduction vs innovative search in R&D. J. Strategy Manag. 2011, 4, 196–214.

- Chikte, S. Dynamic Investment Strategies for a Risky R&D Project. J. Appl. Probab. 1977, 14, 144–152.

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A behavioral theory of the firm. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2003, 4, 81–95.

- Baum, J.A.C.; Rowley, T.J.; Shipilov, A.V.; Chuang, Y.T. Dancing with Strangers: Aspiration Performance and the Search for Underwriting Syndicate Partners. Adm. Sci. Q. 2016, 50, 536–575.

- Chrisman, J.J.; Patel, P.C. Variations in R&D Investments of Family and Nonfamily Firms: Behavioral Agency and Myopic Loss Aversion Perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 55, 976–997.

- Yu, W.; Minniti, M.; Nason, R. Underperformance duration and innovative search: Evidence from the high-tech manufacturing industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 836–861.

- Gamache, D.L.; McNamara, G.; Mannor, M.J.; Johnson, R.E. Motivated to Acquire? The Impact of CEO Regulatory Focus on Firm Acquisitions. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1261–1282.

- Kashmiri, S.; Brower, J. Oops! I did it again: Effect of corporate governance and top management team characteristics on the likelihood of product-harm crises. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 621–630.

- Cho, S.Y.; Arthurs, J.D.; Townsend, D.M.; Miller, D.R.; Barden, J.Q. Performance deviations and acquisition premiums: The impact of CEO celebrity on managerial risk-taking. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2677–2694.

- Mishina, Y.; Dykes, B.J.; Block, E.S.; Pollock, T.G. Why “Good” Firms do Bad Things: The Effects of High Aspirations, High Expectations, and Prominence on the Incidence of Corporate Illegality. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 701–722.

- Derfus, P.J.; Maggitti, P.G.; Grimm, C.M.; Smith, K.G. The Red Queen Effect: Competitive Actions And Firm Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 61–80.

- Ye, Y.; Yu, W.; Nason, R. Performance Feedback Persistence: Comparative Effects of Historical Versus Peer Performance Feedback on Innovative Search. J. Manag. 2020, 47, 1053–1081.

- Lucas, G.; Knoben, J.; Meeus, M. Contradictory yet Coherent? Inconsistency in Performance Feedback and R&D Investment Change. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 658–681.

- Si, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Which forms of R&D internationalisation behaviours promote firm’s innovation performance? An empirical study from the China International Industry Fair 2016–2018. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 33, 857–870.

- Petrou, P.; van den Heuvel, M.; Schaufeli, W. The joint effects of promotion and prevention focus on performance, exhaustion and sickness absence among managers and non-managers. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1493–1507.

- Gino, F.; Kouchaki, M.; Casciaro, T. Why connect? Moral consequences of networking with a promotion or prevention focus. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 199, 1221.

- Ryu, W.; Reuer, J.J.; Brush, T.H. The effects of multimarket contact on partner selection for technology cooperation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 267–289.

- Devarakonda, S.V.; Reuer, J.J. Knowledge Sharing and Safeguarding in R&D Collaborations: The Role of Steering Committees in Biotechnology Alliances. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1912–1934.

- Luu, T.T. Knowledge sharing in the hospitality context: The roles of leader humility, job crafting, and promotion focus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102848.

- Zeng, H.; Zhao, L.; Ruan, S. How Does Mentoring Affect Proteges’ Adaptive Performance in the Workplace: Roles of Thriving at Work and Promotion Focus. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 546152.

- Kim, C.; Park, J.H. Explorative Search for a High-Impact Innovation: The Role of Technological Status in the Global Pharmaceutical Industry. R&D Manag. 2013, 43, 394–406.

- Buchholz, F.; Jaeschke, R.; Lopatta, K.; Maas, K. The use of optimistic tone by narcissistic CEOs. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 531–562.

- Lannon, J.; Walsh, J.N. Paradoxes and partnerships: A study of knowledge exploration and exploitation in international development programmes. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 8–31.

- Zhang, S.; Higgins, E.T.; Chen, G. Managing others like you were managed: How prevention focus motivates copying interpersonal norms. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 647–663.

- Petrou, P.; Baas, M.; Roskes, M. From prevention focus to adaptivity and creativity: The role of unfulfilled goals and work engagement. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 36–48.

- Choi, J.; Rhee, M.; Kim, Y.C. Performance feedback and problemistic search: The moderating effects of managerial and board outsiderness. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 21–33.

- Oiknine, A.H.; Pollard, K.A.; Khooshabeh, P.; Files, B.T. Need for Cognition Is Positively Related to Promotion Focus and Negatively Related to Prevention Focus. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 606847.

- Lavie, D.; Tushman, M.L. Exploration and Exploitation Within and Across Organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 109–155.

- Zimmermann, A.; Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J. How Is Ambidexterity Initiated? The Emergent Charter Definition Process. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 1119–1139.

- Maclean, M.; Harvey, C.; Golant; Sillince, J. The role of innovation narratives in accomplishing organizational ambidexterity. Strateg. Organ. 2020, 19, 693–721.

- Xie, X.; Gao, Y.; Zang, Z.; Meng, X. Collaborative ties and ambidextrous innovation: Insights from internal and external knowledge acquisition. Ind. Innov. 2019, 25, 1–26.