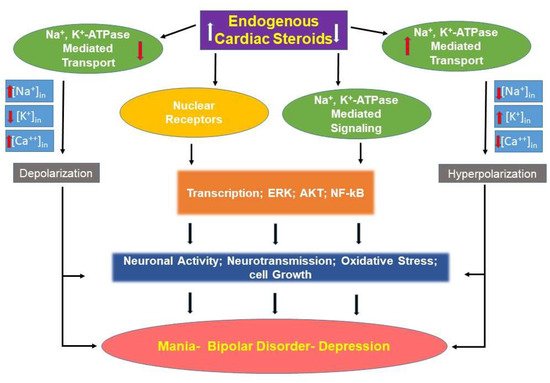

Type I bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe psychiatric illness that manifests as extreme variations in mood and energy, usually labelled as mania and depression, interspersed over a euthymic or dysthymic baseline. Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe psychiatric illness with a poor prognosis and problematic, suboptimal, treatments. Treatments, borne of an understanding of the pathoetiologic mechanisms, need to be developed in order to improve outcomes. Dysregulation of cationic homeostasis is the most reproducible aspect of BD pathophysiology. Correction of ionic balance is the universal mechanism of action of all mood stabilizing medications. Endogenous sodium pump modulators (collectively known as endogenous cardiac steroids, ECS) are steroids which are synthesized in and released from the adrenal gland and brain. These compounds, by activating or inhibiting Na+, K+-ATPase activity and activating intracellular signaling cascades, have numerous effects on cell survival, vascular tone homeostasis, inflammation, and neuronal activity.

- bipolar disorder

- endogenous cardiac steroids

- endogenous ouabain

- ouabain

- Na+

- K+-ATPase

1. Introduction

2. Endogenous Cardiac Steroids in Bipolar Disorder

Cardenolides, such as ouabain and digoxin, and bufadienolides, such as bufalin, are steroids originally identified in plants (Digitalis, Strophantus) and toads (Bufo), which have been used for hundreds of years in Western and Eastern medicine to treat heart failure, arrhythmias, and other maladies. In the past 25 years, the cardenolides ouabain and digoxin, and the bufadienolides 19-norbufalin, marinobufagenin, and cinobufagenin were identified as normal constituents of mammalian tissues, including the brain [21,22,23,24][21][22][23][24]. These compounds, collectively termed endogenous cardiac steroids (ECS), are synthesized in the adrenal and hypothalamus of mammals [25,26[25][26][27],27], and they are considered a new class of hormones implicated in many physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms, including cell growth and cancer, vascular tone homeostasis, blood pressure, hypertension, natriuresis, heart contractility, and inflammation [22,24,28][22][24][28]. These mammalian ECS resemble non-mammalian compounds in their ionotropic effects, presumably due to inhibition of the sodium, and potassium-activated adenosine triphosphatase, or sodium pump (Na+, K+-ATPase) [29]. However, at low physiologic concentrations (nM), these compounds have been shown to stimulate pump activity [30,31,32,33][30][31][32][33]. Importantly, the interaction of ECS with the Na+, K+-ATPase results not only in the inhibition of the ion pumping function, but causes the activation of several signal transduction cascades, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), protein kinase B, and oroto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase pathways [34,35][34][35]. In addition, a substantial body of studies has demonstrated that ECS also act by directly and indirectly affecting the activity of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors [36,37][36][37]. To date, the most studied ECS is the endogenous ouabain (EO); a compound that is similar or identical to the plant steroid. Based on its immunoreactivity with anti-ouabain antibodies, this compound has been shown to be present in mammalian brain and CSF, and it is considered a potential neuromodulator [22,38,39,40][22][38][39][40]. It is important to note that there remains some debate regarding the exact structure of EO [41]. Central to this debate, there is difficulty measuring the picomolar concentrations that exist in mammalian systems using direct chemical methods [42]. Notably, the evidence for the existence of EO is quite overwhelming, and the dispute is focused on the exact structure of this steroid [27]. The synthetic pathways of ECS are not established, but it is known that cholesterol (which may be reduced in the brains of patients with bipolar illness [43]) is needed for ECS/EO production [27], and the pathway may involve pregnenolone and progesterone as intermediate steps [42]. Pregnenolone levels may be reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with a diagnosis of mood disorder, and this reduction may be in relation to the severity of their symptoms [44]. Rapid elevations in plasma levels of ECS, as occurs with exhaustive exercise of normal controls [45], may occur due to the release of bound steroids from a carrier protein [46]. Despite the limited available data on the metabolism of ECS in general, and EO in particular, these compounds are referred to by some as “a hormone family” [21,27,47,48,49,50,51,52][21][27][47][48][49][50][51][52]. However, at the same time, as is evident from the lack of reference in textbooks and reviews, these steroids are ignored almost completely by mainstream biochemists, physiologists, and endocrinologists. WThe researchers pointed out the crucial importance of deciphering the biosynthetic pathway of ECS close to ten years ago [53], but this issue remained the Achilles heel of this field of research. At experimental or pharmacologic micromolar concentrations, exogenously administered ouabain inhibits the activity of the sodium pump. However, at physiologic picomolar to nanomolar concentrations, EO increases sodium pump activity [30,31,32,33][30][31][32][33]. In notable cases, when there are documented increases of the plasma levels of EO, the total levels remain below concentrations that inhibit sodium pump activity [54]. At the low concentrations, EO also appear to activate second messengers of the Src kinase-, ERK1/2-, and Akt-mediated pathways or the sodium-proton exchanger 1 (NHE1) [54,55,56,57][54][55][56][57]. Activation of the sodium pump appears to be an essential feature in reducing central nervous system inflammation [58]. If sodium pump activity is blocked in glial cells, inflammatory pathways are activated in the presence of lipopolysaccharides [58].2.1. Role of Exogenous CS and ECS in Animal Models of Mood Disorders

2.2. Role of ECS in Humans Mood Disorders

2.3. Hypothesis

2.4. Translational Implications: Pathophysiologic Models

2.5. EO Excess

2.6. Relative EO Deficiency

References

- Ketter, T.A.; Calabrese, J.R. Stabilization of mood from below versus above baseline in bipolar disorder: A new nomenclature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 63, 146–151.

- Clemente, A.S.; Diniz, B.S.; Nicolato, R.; Kapczinski, F.P.; Soares, J.C.; Firmo, J.O.; Castro-Costa, É. Bipolar disorder prevalence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 155–161.

- Grande, I.; Berk, M.; Birmaher, B.; Vieta, E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2016, 387, 1561–1572.

- Cipriani, G.; Danti, S.; Carlesi, C.; Cammisuli, D.M.; Di Fiorino, M. Bipolar Disorder and Cognitive Dysfunction: A Complex Link. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 743–756.

- Dome, P.; Rihmer, Z.; Gonda, X. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder: A brief review. Medicina 2019, 55, 403.

- Belvederi Murri, M.; Prestia, D.; Mondelli, V.; Pariante, C.; Patti, S.; Olivieri, B.; Arzani, C.; Masotti, M.; Respino, M.; Antonioli, M. The HPA axis in bipolar disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 63, 327–342.

- Nestler, E.J.; Peña, C.J.; Kundakovic, M.; Mitchell, A.; Akbarian, S. Epigenetic Basis of Mental Illness. Neuroscientist 2016, 22, 447–463.

- Takaesu, Y. Circadian rhythm in bipolar disorder: A review of the literature. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 673–682.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Yff, T.; Gao, Y. Ion Dysregulation in the Pathogenesis of Bipolar Illness. Ann. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 3, 1076.

- Askland, K. Toward a biaxial model of “bipolar” affective disorders: Further exploration of genetic, molecular and cellular substrates. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 94, 35–66.

- Judy, J.T.; Zandi, P.P. A review of potassium channels in bipolar disorder. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 105.

- Lichtstein, D.; Ilani, A.; Rosen, H.; Horesh, N.; Singh, S.V.; Buzaglo, N.; Hodes, A. Na⁺, K⁺-ATPase Signaling and Bipolar Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2314.

- Mack, A.A.; Gao, Y.; Ratajczak, M.Z.; Kakar, S.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Review of animal models of bipolar disorder that alter ion regulation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 208–214.

- Valvassori, S.S.; Dal-Pont, G.C.; Resende, W.R.; Varela, R.B.; Lopes-Borges, J.; Cararo, J.H.; Quevedo, J. Validation of the animal model of bipolar disorder induced by ouabain: Face, construct and predictive perspectives. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 158.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Huff, M.O. Mood stabilizers and ion regulation. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2001, 9, 23–32.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Paskitti, M.E. The ketogenic diet may have mood-stabilizing properties. Med. Hypotheses 2001, 57, 724–726.

- Roberts, R.J.; Repass, R.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Effect of dopamine on intracellular sodium: A common pathway for pharmacological mechanism of action in bipolar illness. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 11, 181–187.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Wyatt, R.J. The Na,K-ATPase hypothesis for bipolar illness. Biol. Psychiatry 1995, 37, 235–244.

- Looney, S.W.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Meta-analysis of erythrocyte Na,K-ATPase activity in bipolar illness. Depress. Anxiety 1997, 5, 53–65.

- Singh, S.V.; Fedorova, O.V.; Wei, W.; Rosen, H.; Horesh, N.; Ilani, A.; Lichtstein, D. Na+, K+-ATPase α isoforms and endogenous cardiac steroids in prefrontal cortex of bipolar patients and controls. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5912.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Gao, Y.; You, P. Role of endogenous ouabain in the etiology of bipolar disorder. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2021, 9, 6.

- Bagrov, A.Y.; Shapiro, J.I.; Fedorova, O.V. Endogenous cardiotonic steroids: Physiology, pharmacology, and novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009, 61, 9–38.

- Hodes, A.; Lichtstein, D. Natriuretic hormones in brain function. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 201.

- Blaustein, M.P.; Hamlyn, J.M. Ouabain, endogenous ouabain and ouabain-like factors: The Na+ pump/ouabain receptor, its linkage to NCX, and its myriad functions. Cell Calcium 2020, 86, 102159.

- Lichtstein, D.; Steinitz, M.; Gati, I.; Samuelov, S.; Deutsch, J.; Orly, J. Biosynthesis of digitalis-like compounds in rat adrenal cells: Hydroxycholesterol as possible precursor. Life Sci. 1998, 62, 2109–2126.

- El-Masri, M.A.; Clark, B.J.; Qazzaz, H.M.; Valdes, R., Jr. Human adrenal cells in culture produce both ouabain-like and dihydroouabain-like factors. Clin. Chem. 2002, 48, 1720–1730.

- Blaustein, M.P. The pump, the exchanger, and the holy spirit: Origins and 40-year evolution of ideas about the ouabain-Na+ pump endocrine system. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2018, 314, C3–C26.

- Cavalcante-Silva, L.H.A.; Lima, É.A.; Carvalho, D.C.M.; de Sales-Neto, J.M.; Alves, A.K.A.; Galvão, J.G.F.M.; da Silva, J.S.F.; Rodrigues-Mascarenhas, S. Much more than a cardiotonic steroid: Modulation of inflammation by ouabain. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 895.

- Whayne, T.F., Jr. Clinical use of digitalis: A state of the art review. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2018, 18, 427–440.

- Ghysel-Burton, J.; Godfraind, T. Stimulation and inhibition of the sodium pump by cardioactive steroids in relation to their binding sites and their inotropic effects on guinea-pig isolated atria. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1979, 66, 175–184.

- Lichtstein, D.; Samuelov, S.; Bourrit, A. Characterization of the stimulation of neuronal Na+, K+-ATPase activity by low concentrations of ouabain. Neurochem. Int. 1985, 7, 709–715.

- Gao, J.; Wymore, R.S.; Wang, Y.; Gaudette, G.R.; Krukenkamp, I.B.; Cohen, I.S.; Mathias, R.T. Isoform-specific stimulation of cardiac Na/K pumps by nanomolar concentrations of glycosides. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002, 119, 297–312.

- Dvela-Levitt, M.; Cohen-Ben Ami, H.; Rosen, H.; Ornoy, A.; Hochner-Celnikier, D.; Granat, M.; Lichtstein, D. Reduction in maternal circulating ouabain impairs offspring growth and kidney development. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1103–1114.

- Xie, Z.; Cai, T. Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated signal transduction: From protein interaction to cellular function. Mol. Interv. 2003, 3, 157–168.

- Bejček, J.; Spiwok, V.; Kmoníčková, E.; Rimpelová, S. Na+/K+-ATPase revisited: On its mechanism of action, role in cancer, and activity modulation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1905.

- Wang, Y.; Lonard, D.M.; Yu, Y.; Chow, D.C.; Palzkill, T.G.; Wang, J.; Qi, R.; Matzuk, A.J.; Song, X.; Madoux, F.; et al. Bufalin is a potent small-molecule inhibitor of the steroid receptor coactivators SRC-3 and SRC-1. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1506–1517.

- Karaś, K.; Sałkowska, A.; Dastych, J.; Bachorz, R.A.; Ratajewski, M. Cardiac glycosides with target at direct and indirect interactions with nuclear receptors. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110106.

- Lichtstein, D.; Rosen, H. Endogenous digitalis-like Na+,K+-ATPase inhibitors, and brain function. Neurochem. Res. 2001, 26, 971–978.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Miller, J.; Valdes RJr Cassis, T.B.; Li, R. Digoxin-like immunoreactive factor (DLIF) in human cerebrospinal fluid. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 91.

- Hamlyn, J.M.; Blaustein, M.P. Endogenous ouabain: Recent advances and controversies. Hypertension 2016, 68, 526–532.

- Kaaja, R.J.; Nicholls, M.G. Does the hormone “endogenous ouabain” exist in the human circulation? Biofactors 2018, 44, 219–221.

- Baecher, S.; Kroiss, M.; Fassnacht, M.; Vogeser, M. No endogenous ouabain is detectable in human plasma by ultra-sensitive UPLC-MS/MS. Clin. Chim. Acta 2014, 431, 87–92.

- Beasley, C.L.; Honer, W.G.; Bergmann, K.; Falkai, P.; Lütjohann, D.; Bayer, T.A. Reductions in cholesterol and synaptic markers in association cortex in mood disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005, 7, 449–455.

- George, M.S.; Guidotti, A.; Rubinow, D.; Pan, B.; Mikalauskas, K.; Post, R.M. CSF neuroactive steroids in affective disorders: Pregnenolone, progesterone, and DBI. Biol. Psychiatry 1994, 35, 775–780.

- Valdes, R.; Hagberg, J.M.; Vaughan, T.E.; Lau, B.W.C.; Seals, D.R.; Ehsani, A.A. Endogenous digoxin-like immunoreactivity in blood is increased during prolonged strenuous exercise. Life Sci. 1988, 42, 103–110.

- Antolovic, R.; Bauer, N.; Mohadjerani, M.; Kost, H.; Neu, H.; Kirch, U.; Grünbaum, E.G.; Schoner, W. Endogenous ouabain and its binding globulin: Effects of physical exercise and study on the globulin’s tissue distribution. Hypertens. Res. 2000, 23, S93–S98.

- Nesher, M.; Shpolansky, U.; Rosen, H.; Lichtstein, D. The digitalis-like steroid hormones: New mechanisms of action and biological significance. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 2093–2107.

- Simonini, M.; Casanova, P.; Citterio, L.; Messaggio, E.; Lanzani, C.; Manunta, P. Endogenous ouabain and related genes in the translation from hypertension to renal diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1948.

- Sajeevadathan, M.; Pettitt, M.J.; Buhr, M. Interaction of ouabain and progesterone on induction of bull sperm capacitation. Theriogenology 2019, 126, 191–198.

- Leenen, F.H.H.; Wang, H.W.; Hamlyn, J.M. Sodium pumps, ouabain and aldosterone in the brain: A neuromodulatory pathway underlying salt-sensitive hypertension and heart failure. Cell Calcium 2020, 86, 102151.

- Pirkmajer, S.; Bezjak, K.; Matkovič, U.; Dolinar, K.; Jiang, L.Q.; Miš, K.; Gros, K.; Milovanova, K.; Pirkmajer, K.P.; Marš, T.; et al. Ouabain suppresses IL-6/STAT3 signaling and promotes cytokine secretion in cultured skeletal muscle cells. Front. Physiol 2020, 11, 566584.

- Ogazon Del Toro, A.; Jimenez, L.; Serrano Rubi, M.; Cereijido, M.; Ponce, A. Ouabain enhances gap junctional intercellular communication by inducing paracrine secretion of prostaglandin E2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6244.

- Lichtstein, D.; Rosen, H.; Dvela, M. Cardenolides and bufadienolides as hormones: What is missing? Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2012, 302, F957–F958.

- Holthouser, K.A.; Mandal, A.; Merchant, M.L.; Schelling, J.R.; Delamere, N.A.; Valdes RJr et, a.l. Ouabain stimulates Na-K-ATPase through a sodium/hydrogen exchanger-1 (NHE-1)-dependent mechanism in human kidney proximal tubule cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2010, 299, F77–F90.

- Liang, M.; Cai, T.; Tian, J.; Qu, W.; Xie, Z.J. Functional characterization of Src-interacting Na/K-ATPase using RNA interference assay. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 19709–19719.

- Khundmiri, S.J.; Amin, V.; Henson, J.; Lewis, J.; Ameen, M.; Rane, M.J.; Delamere, N.A. Ouabain stimulates protein kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation in opossum kidney proximal tubule cells through an ERK-dependent pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007, 293, C1171–C1180.

- Khundmiri, S.J.; Ameen, M.; Delamere, N.A.; Lederer, E.D. PTH-mediated regulation of Na+-K+-ATPase requires Src kinase-dependent ERK phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2008, 295, F426–F437.

- Kinoshita, P.F.; Yshii, L.M.; Orellana, A.M.M.; Paixão, A.G.; Vasconcelos, A.R.; Lima, L.S.; Kawamoto, E.M.; Scavone, C. Alpha 2 Na+,K+-ATPase silencing induces loss of inflammatory response and ouabain protection in glial cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4894.

- Robbins, T.W.; Sahakian, B.J. Animal models of mania. In Mania: An Evolving Concept; Bellmaker, R.H., Ban Prang, H.M., Eds.; Spectrum: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 143–216.

- Feier, G.; Valvassori, S.S.; Varela, R.B.; Resende, W.R.; Bavaresco, D.V.; Morais, M.O.; Scaini, G.; Andersen, M.L.; Streck, E.L.; Quevedo, J. Lithium and valproate modulate energy metabolism in an animal model of mania induced by methamphetamine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2013, 103, 589–596.

- Berggren, U.; Tallstedt, L.; Ahlenius, S.; Engel, J. The effect of lithium on amphetamine-induced locomotor stimulation. Psychopharmacology 1978, 59, 41–45.

- Hodes, A.; Rosen, H.; Deutsch, J.; Lifschytz, T.; Einat, H.; Lichtstein, D. Endogenous cardiac steroids in animal models of mania. Bipolar Disord. 2016, 18, 451–459.

- Zugno, A.I.; Valvassori, S.S.; Scherer, E.B.; Mattos, C.; Matté, C.; Ferreira, C.L.; Rezin, G.T.; Wyse, A.T.; Quevedo, J.; Streck, E.L. Na+,K+-ATPase activity in an animal model of mania. J. Neural. Transm. 2009, 116, 431–436.

- Dias, V.T.; Trevizol, F.; Barcelos, R.C.; Kunh, F.T.; Roversi, K.; Schuster, A.J.; Pase, C.S.; Golombieski, R.; Emanuelli, T.; Bürger, M.E. Lifelong consumption of trans fatty acids promotes striatal impairments on Na(+)/K(+) ATPase activity and BDNF mRNA expression in an animal model of mania. Brain Res. Bull 2015, 118, 78–81.

- Pendyala, G.; Buescher, J.L.; Fox, H.S. Methamphetamine and inflammatory cytokines increase neuronal Na+/K+-ATPase isoform 3: Relevance for HIV associated neurocognitive disorders. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37604.

- Rosenblat, J.D.; McIntyre, R.S. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 39, 125–137.

- Khansari, N.; Shakiba, Y.; Mahmoudi, M. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2009, 3, 73–80.

- Brietzke, E.; Stertz, L.; Fernandes, B.S.; Kauer-Sant’anna, M.; Mascarenhas, M.; Escosteguy Vargas, A.; Chies, J.A.; Kapczinski, F. Comparison of cytokine levels in depressed, manic and euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 116, 214–217.

- Hodes, A.; Lifschytz, T.; Rosen, H.; Cohen Ben-Ami, H.; Lichtstein, D. Reduction in endogenous cardiac steroids protects the brain from oxidative stress in a mouse model of mania induced by amphetamine. Brain Res. Bull. 2018, 137, 356–362.

- Ruktanonchai, D.J.; El-Mallakh, R.S.; Li, R.; Levy, R.S. Persistent hyperactivity following a single intracerebroventricular dose of ouabain. Physiol. Behav. 1998, 63, 403–406.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; El-Masri, M.A.; Huff, M.O.; Li, X.P.; Decker, S.; Levy, R.S. Intracerebroventricular administration of ouabain as a model of mania in rats. Bipolar Disord. 2003, 5, 362–365.

- Hamid, H.; Gao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Hougland, M.T.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Effect of ouabain on sodium pump alpha-isoform expression in an animal model of mania. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 33, 1103–1106.

- Gao, Y.; Jhaveri, M.; Lei, Z.; Chaneb, B.L.; Lingrel, J.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Glial-specific gene alterations associated with manic behaviors. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2013, 1, 20.

- Clapcote, S.J.; Duffy, S.; Xie, G.; Kirshenbaum, G.; Bechard, A.R.; Rodacker Schack, V.; Petersen, J.; Sinai, L.; Saab, B.J.; Lerch, J.P.; et al. Mutation I810N in the alpha3 isoform of Na+,K+-ATPase causes impairments in the sodium pump and hyperexcitability in the CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14085–14090.

- Kirshenbaum, G.S.; Clapcote, S.J.; Duffy, S.; Burgess, C.R.; Petersen, J.; Jarowek, K.J.; Yücel, Y.H.; Cortez, M.A.; Snead, O.C., 3rd; Vilsen, B.; et al. Mania-like behavior induced by genetic dysfunction of the neuron-specific Na+,K+-ATPase α3 sodium pump. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18144–18149.

- Kirshenbaum, G.S.; Clapcote, S.J.; Petersen, J.; Vilsen, B.; Ralph, M.R.; Roder, J.C. Genetic suppression of agrin reduces mania-like behavior in Na+, K+-ATPase alpha3 mutant mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2012, 11, 436–443.

- Hougland, M.T.; Gao, Y.; Herman, L.; Ng, C.K.; Lei, Z.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose-F18 in an animal model of mania. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 164, 166–171.

- Kim, S.H.; Yu, H.S.; Park, H.G.; Jeon, W.J.; Song, J.Y.; Kang, U.G.; Ahn, Y.M.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, Y.S. Dose-dependent effect of intracerebroventricular injection of ouabain on the phosphorylation of the MEK1/2-ERK1/2-p90RSK pathway in the rat brain related to locomotor activity. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 1637–1642.

- Goldstein, I.; Lax, E.; Gispan-Herman, I.; Ovadia, H.; Rosen, H.; Yadid, G.; Lichtstein, D. Neutralization of endogenous digitalis-like compounds alters catecholamines metabolism in the brain and elicits anti-depressive behavior. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 22, 72–79.

- Grider, G.; El-Mallakh, R.S.; Huff, M.O.; Buss, T.J.; Miller, J.; Valdes, R.J.r. Endogenous digoxin-like immunoreactive factor (DLIF) serum concentrations are decreased in manic bipolar patients compared to normal controls. J. Affect. Disord. 1999, 54, 261–267.

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Stoddard, M.; Jortani, S.A.; El-Masri, M.A.; Sephton, S.; Valdes, R.J.r. Aberrant regulation of endogenous ouabain-like factor in bipolar subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 178, 116–120.

- Gao, Y.; Akers, B.; Roberts, M.B.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Corticosterone response in sleep deprivation and sleep fragmentation. J. Sleep Disord. Manag. 2017, 3, 18.

- Puzyński, S.; Beresewicz, M.; Bidzińska, E.; Bogdanowicz, E.; Kalinowski, A.; Koszewska, I.; Swiecicki, L. Reaction to sleep deprivation as a prognostic factor in the treatment of endogenous depression. Psychiatr. Pol. 1991, 25, 83–89, In Polish.

- Von Treuer, K.; Norman, T.R.; Armstrong, S.M. Overnight human plasma melatonin, cortisol, prolactin, TSH, under conditions of normal sleep, sleep deprivation, and sleep recovery. J. Pineal Res. 1996, 20, 7–14.

- Voderholzer, U.; Hohagen, F.; Klein, T.; Jungnickel, J.; Kirschbaum, C.; Berger, M.; Riemann, D. Impact of sleep deprivation and subsequent recovery sleep on cortisol in unmedicated depressed patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1404–1410.

- Morales, J.; Yáñez, A.; Fernández-González, L.; Montesinos-Magraner, L.; Marco-Ahulló, A.; Solana-Tramunt, M.; Calvete, E. Stress and autonomic response to sleep deprivation in medical residents: A comparative cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214858.

- Song, H.-T.; Sun, X.-Y.; Yang, T.-S.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Yang, J.-L.; Bai, J. Effects of sleep deprivation on serum cortisol level and mental health in servicemen. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015, 96, 169–175.

- Mynett-Johnson, L.; Murphy, V.; McCormack, J.; Shields, D.C.; Claffey, E.; Manley, P.; McKeon, P. Evidence for an allelic association between bipolar disorder and a Na+, K+ adenosine triphosphatase alpha subunit gene (ATP1A3). Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 44, 47–51.

- Hodes, A.; Rosen, H.; Cohen-Ben Ami, H.; Lichtstein, D. Na+, K+-ATPase α3 isoform in frontal cortex GABAergic neurons in psychiatric diseases. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 115, 21–28.

- Goldstein, I.; Levy, T.; Galili, D.; Ovadia, H.; Yirmiya, R.; Rosen, H.; Lichtstein, D. Involvement of Na+, K+-ATPase and endogenous digitalis-like compounds in depressive disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 60, 491–499.

- Goldstein, I.; Lerer, E.; Laiba, E.; Mallet, J.; Mujaheed, M.; Laurent, C.; Rosen, H.; Ebstein, R.P.; Lichtstein, D. Association between sodium- and potassium-activated adenosine triphosphatase alpha isoforms and bipolar disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 985–991.

- Rose, A.M.; Mellett, B.J.; Valdes RJr Kleinman, J.E.; Herman, M.M.; Li, R.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Alpha 2 isoform of the Na,K-adenosine triphosphatase is reduced in temporal cortex of bipolar individuals. Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 44, 892–897.

- Saiyad, M.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Smoking is associated with greater symptom load in bipolar disorder patients. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 24, 305–309.

- Miller, C.L.; Yolken, R.H. Methods to optimize the generation of cDNA from postmortem human brain tissue. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 2003, 10, 156–167.

- Xie, Z.; Xie, J. The Na/K-ATPase-mediated signal transduction as a target for new drug development. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 3100–3109.

- Nguyen, A.N.; Wallace, D.P.; Blanco, G. Ouabain binds with high affinity to the Na,K-ATPase in human polycystic kidney cells and induces extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and cell proliferation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 46–57.

- Bezchlibnyk, Y.; Young, L.T. The neurobiology of bipolar disorder: Focus on signal transduction pathways and the regulation of gene expression. Can. J. Psychiatry 2002, 47, 135–148.

- Chuang, D.M. The antiapoptotic actions of mood stabilizers: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1053, 195–204.

- Cochet-Bissuel, M.; Lory, P.; Monteil, A. The sodium leak channel, NALCN, in health and disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 132.

- Schroeder, E.; Gao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Roisen, F.; El-Mallakh, R.S. The gene BRAF is underexpressed in bipolar subject olfactory neuroepithelial progenitor cells undergoing apoptosis. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 236, 130–135.

- Altamirano, J.; Li, Y.; DeSantiago, J.; Piacentino V 3rd Houser, S.R.; Bers, D.M. The inotropic effect of cardioactive glycosides in ventricular myocytes requires Na+-Ca2+ exchanger function. J. Physiol. 2006, 575, 845–854.

- Srikanthan, K.; Shapiro, J.I.; Sodhi, K. The role of Na/K-ATPase signaling in oxidative stress related to obesity and cardiovascular disease. Molecules 2016, 21, 1172.

- Berendes, E.; Cullen, P.; Van Aken, H.; Zidek, W.; Erren, M.; Hübschen, M.; Weber, T.; Wirtz, S.; Tepel, M.; Walter, M. Endogenous glycosides in critically ill patients. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 1331–1337.